(1)

Cognitive Function Clinic, Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool, UK

Abstract

This chapter examines referral patterns to a dedicated secondary care neurology-led cognitive disorders clinic in terms of numbers seen over the period 2002–2013, sources (primary and secondary care), patient age, and casemix in terms of diagnosis. Although referrals have increased, the proportion of dementia diagnoses has not changed, indicating the persistence of a dementia diagnosis gap.

Keywords

DementiaDiagnosisReferral patternsIt is a truth universally acknowledged that dementia is now a major global public health issue, set to increase as the world population ages (Ferri et al. 2005). In 2010, a global cost of illness study suggested a “base case option” figure of US$604 billion, equivalent to the 18th largest national economy in the world (between Turkey and Indonesia), and larger than the revenue of the world’s largest companies (Wal-Mart, Exxon Mobil). In high income countries, which accounted for 89 % of the costs but only 46 % of dementia prevalence, this is mostly due to direct costs of social care, whilst in low and middle income countries, which accounted for only 11 % of the costs but 54 % of dementia prevalence, this is mostly due to informal care costs (Wimo and Prince 2010). The need to address these issues is obvious, from the human as well as the economic standpoint, and will require governments to make dementia a priority, with the development of policies, investment in chronic care, and funding of research.

Faced with such enormities, what can the individual clinician hope to contribute? The National Dementia Strategy (NDS) for England (Department of Health 2009) proposed three key themes to address the problem of dementia: improved awareness, early diagnosis and intervention, and a higher quality of care. Many of the 17 “key objectives” fell outwith the clinical domain, such as an information campaign to raise awareness and reduce stigma, and improvement in community personal support services, housing support and care homes. However, the early identification and appropriate initial management of dementia cases may be deemed to fall squarely within the remit of the individual clinician. The first issue to address, therefore, is the referral routes by which such patients arrive at the clinical encounter.

1.1 Referral Numbers

Referrals to the Cognitive Function Clinic (CFC) represent a small but relatively complex caseload. Generally it may be said that the assessment and diagnosis of patients with memory complaints and/or cognitive disorders is ill-suited to the workings of general neurological outpatient clinics, partly for lack of adequate time to assess fully the history and cognitive performance of these patients.

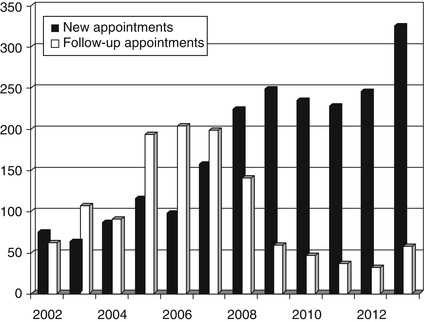

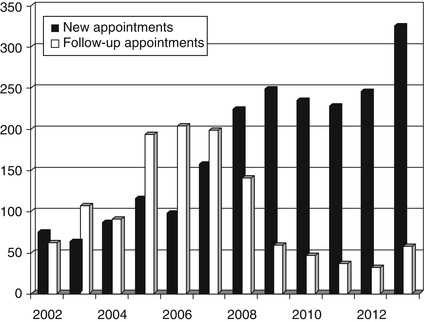

Referral numbers to the author’s clinic have gradually escalated over time (Fig. 1.1), which may possibly be a reflection of increasing public awareness of dementia. Numbers seen in 2008–2013 are more than twice those seen in 2002–2007, as reflected in recruitment for studies. For example, more patients were recruited in 6 months in 2013 than in 2 years in 2004–2006 in the analysis of primary care use of cognitive screening instruments (see below, Sect. 1.2.1, and Table 1.3 first row; for another example of doubled referral rate, see sequential studies on “Attended alone” sign, Sect. 3.2.1).

Figure 1.1

Referral numbers to CFC, 2002–2013

However, this change may perhaps be contrary to the expectations of national policy documents such as the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence/Social Care Institute for Excellence (NICE/SCIE 2006), which, requiring a “single point of referral” for all cases (de facto, old age psychiatry), might have been anticipated to erode referrals to a neurology-led clinic. In fact, comparing the 2 years immediately pre- and post- publication of the NICE/SCIE guidelines (Larner 2009a) there was a 79 % increase in new referrals seen. Likewise, there was a 12 % increase in the number of referrals comparing the 12-month periods immediately before and after the launch of the NDS (Larner 2010).

The fall off in numbers of follow-up appointments post 2008 was occasioned by the decommissioning of CFC prescriptions for cholinesterase inhibitors for financial reasons. It is possible that memory clinics may be no more effective than primary care practitioners for post-diagnosis treatment and coordination of care for dementia patients, as shown in a study from the Netherlands (Meeuwsen et al. 2012), although inevitably the cohort of patients readily available for clinical trials of novel drugs is reduced.

1.2 Referral Sources

The vast majority of referrals to CFC have come from three sources: primary care physicians (general practitioners), psychiatrists, and neurologists.

1.2.1 Primary Care

The majority of referrals to CFC have been initiated by general practitioners (GPs) working in primary care, in excess of 50 % (e.g. Fisher and Larner 2007; Fearn and Larner 2009). This proportion has increased to around 70 % following publication of national directives (NICE/SCIE, NDS; Larner 2009a, 2010; Menon and Larner 2011; Ghadiri-Sani and Larner 2014), suggesting that awareness of the problem of dementia has been raised amongst primary care physicians (Table 1.1; see also Sects. 9.5.1 and 9.5.3).

Table 1.1

Referral numbers, sources and diagnoses before and after NICE/SCIE and NDS launch (Menon and Larner 2011)

(Sept 2002-August 2004) (Larner 2005a) | Before NICE/SCIE launch (Oct 2004-Sept 2006) (Fisher and Larner 2007) | Before NDS launch (Feb 2008-Feb 2009) | After NDS launch (Feb 2009-Feb 2010) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

New referrals seen | 183 | 231 | 225 | 252 |

Dementia (prevalence in cohort) | 90 (49.2) | 117 (50.6) | 74 (32.9) | 75 (29.8) |

New referrals from primary care (% of total new referrals) | 90 (49.2) | 123 (53.2) | 131 (58.2) | 175 (70.2) |

Primary care referrals with new diagnosis of dementia (% primary care referrals) | 36 (40.0) | 45 (36.6) | 28 (21.3) | 42 (24.0) |

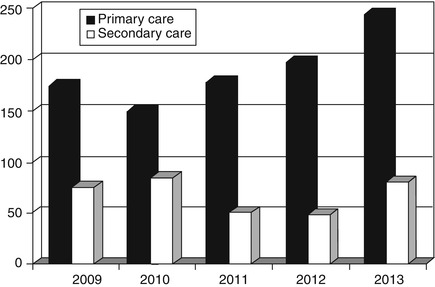

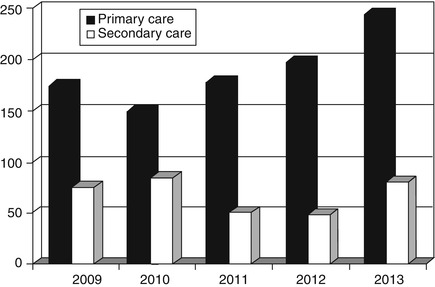

A closer analysis of referrals in the 5-year period 2009–2013 has permitted referral source patterns to be addressed (Table 1.2; Fig. 1.2; Larner 2014). The null hypothesis that the proportion of patients referred to CFC from primary care over this period did not differ significantly was rejected (χ2 = 22.1, df = 4, p < 0.001).

Table 1.2

Referral numbers, sources and diagnoses, CFC 2009–2013 (see Table 1.5 for a breakdown of sources of secondary care referrals)

Year | N | Referral source | Diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Primary care (%) | Secondary care (%) | Dementia (% of N) | No dementia (% of N) | MCI (% of N; % of no dementia) | ||

2009 | 249 | 174 (70) | 75 (30) | 76 (31) | 173 (69) | 30 (12; 17) |

2010 | 233 | 149 (64) | 84 (36) | 71 (30) | 162 (70) | 25 (11; 15) |

2011 | 227 | 177 (78) | 50 (22) | 53 (23) | 174 (77) | 39 (17; 22) |

2012 | 245 | 197 (80) | 48 (20) | 67 (27) | 178 (73) | 40 (16; 22) |

2013 | 323 | 243 (75) | 80 (25) | 88 (27) | 235 (73) | 66 (20; 28) |

Total | 1,277 | 940 (74) | 337 (26) | 355 (28) | 922 (72) | 200 (16; 22) |

Figure 1.2

Referral sources, 2009–2013

The frequency of dementia diagnosis is consistently lower in this referral cohort from primary care than in patient groups referred from secondary care (Larner 2005a; Fisher and Larner 2007; Menon and Larner 2011). There is some evidence for increasing numbers of referrals of “worried well” patients from primary care (see Sect. 9.5.3). Whilst it is accepted that making a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive disorder is not the only function of CFC, and that reassurance of the “worried well” may be deemed an important function, nonetheless establishing dementia diagnoses is key to the purposes of such clinics.

Why should primary care referrals have the lowest “hit rate” for dementia diagnosis? It might be argued that with the possibility of longitudinal (i.e. intraindividual) patient assessment, GPs are well placed to detect cognitive change in their patients (Fisher and Larner 2006), unlike practitioners in secondary care who generally have to make a cross sectional (i.e. interindividual) assessment. Change in patient function might be suggested to primary care physicians by missed appointments, repeated phone calls on the same topic, and poor medication concordance. On the other hand, there has undoubtedly been a certain antipathy to making dementia diagnoses in primary care for various reasons, including therapeutic nihilism and lack of confidence related to inadequate training in this area (O’Connor et al. 1988; Audit Commission, 2002). Failure to administer cognitive screening instruments (CSI; see Chap. 4) may also be a contributory factor (Fisher and Larner 2007; Menon and Larner 2011; Ghadiri-Sani and Larner 2014).

Examination of referral letters from primary care physicians to CFC looking for evidence of CSI use prior to referral was undertaken in two 2-year cohorts, covering the periods October 2004-September 2006 (Fisher and Larner 2007) and February 2008-February 2010 (Menon and Larner 2011; Table 1.3, three left-hand columns). The first study found that in 20.3 % of GP referrals (25/123) a specific CSI was mentioned, and in the second study this had risen to 26.5 % (81/306), a change which did not permit rejection of the null hypothesis (χ2 = 1.54, df = 1, p > 0.1).

Table 1.3

Cognitive test instruments reported in primary care referrals

Before NICE/SCIE launch (Oct 2004-Sept 2006) | Before NDS launch (Feb 2008-Feb 2009) | After NDS launch (Feb 2009-Feb 2010) | (July-Dec 2012) | (July-Dec 2013) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N | 123 | 131 | 175 | 99 | 140 |

Any instrument used (%) | 25 (20.3) | 34 (25.9) | 47 (26.8) | 44 (31.4) | |

Cognitive tests: | |||||

MMSE | 17 | 31 | 29 | 13 | |

AMTS | 6 | 2 | 11 | 6 | |

Clock test | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

6CIT | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 8 |

GPCOG

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||||