, Damien Gervasoni1 and Catherine Vogt2

(1)

Lyon Neuroscience Research Centre CNRS UMR 5292–INSERM U 1028, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France

(2)

Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France

Abbreviations

ASPA

Animal Scientific Procedures Act

AWA

Animal Welfare Act

AWB

Animal Welfare Body

AWRs

Animal Welfare Act and Regulations

CBC

Complete Blood Count

CCAC

Canadian Council on Animal Care

EKG

Electrocardiogram

FELASA

Federation for Laboratory Animal Science Associations

g

gram

IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

ILAR

Institute for Laboratory Animal Research

NIH

National Institute of Health

NTS

Nontechnical Summaries

OACU

Office of Animal Care and Use

PHS

Public Health Service

UK

United Kingdom

US

United States

USDA

United States Department of Agriculture

1.1 Purpose of Law and Regulations

The use of animals in research still arouses intense debate. Its necessity, justification, and acceptability are matters of widely varying opinions, mainly based on moral convictions. There is, however, a consensus to allow animal research as long as no valid alternative method exists to reach the objective. Most countries have their own legislative framework concerning animal research, and this chapter briefly presents examples of laws and regulations, some of which are currently being updated. The purpose of this non-exhaustive enumeration is not to compare their respective strengths or to highlight a country having prior claim in this matter but to illustrate concepts that are common to most legislation and to provide the reader with references and resources.

All researchers, regardless of their area of specialty, should be aware of the laws and policies on the use of animals for experimental and other scientific purposes in force in their country. Besides the legal aspect of animal experimentation, users are strongly advised to follow the latest principles and guidelines for animal care and use available in their own institution, in particular on anesthesia and humane euthanasia procedures. Interactions with local animal welfare bodies such as Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), a referent veterinarian, together with a proactive search of the latest available knowledge or alternative method should be encouraged. Valuable publications and resources are available and regularly updated. These include the guidelines and recommendations from the Federation for Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA) (Voipio et al. 2008; Guillen 2012), the guidelines from the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (ILAR) (Committee on Recognition and Alleviation of Pain in Laboratory Animals et al. 2009; Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals et al. 2011),1 the Canadian research Council on Animal Care (CCAC) in Science (2013a, b),2 and the website of the UK National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs).3

With the revised Directive 2010/63/EU for the protection of laboratory animals4 that took effect on January 1, 2013, Europe has recently reinforced the implementation of the principle of the three Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement), originally put forward by Russell and Burch in their “The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique” (Russell and Burch 1959)5 on the use of animals for experimental and other scientific purposes (see also Appendix 6). While its ultimate goal is to replace the use of animals, this new Directive acknowledges that animals are still needed for research, especially basic research. As in the preceding Directive (86/609/EEC), an appropriate education and training is required for all those engaged in the use of live vertebrate animals for scientific purposes. The new Directive 2010/63/EU distinguishes the following functions: (a) carrying out procedures on animals, (b) designing procedures and projects, (c) taking care of animals, and (d) killing animals (Article 23, Directive 2010/63/EU).6 Persons involved in tasks a, c, and d must be supervised until they have demonstrated the requisite competence; persons in charge of designing procedures and projects (b) must have received instruction in the relevant scientific discipline and have species-specific knowledge. Individuals working with animals should thus have and maintain state-of-the-art knowledge and skills concerning the constant improvements in laboratory animal sciences and animal use in research. The minimum requirements with regard to education and training are enumerated in Annex V of the Directive 2010/63/EU. Appropriate qualification and experience are especially required for surgery. The new legislation updates the minimum standards for animal housing and training of users and aims to improve animal welfare. The revised Directive notably introduces measures that strengthen the evaluation of the need of animal use: if not already common practice, getting approval by an Ethics Committee on animal use prior to the work commencing is now mandatory in the 27 member states. According to the terms of the revised Directive (Article 36–41, Directive 2010/63/EU), authorization for the conduct of a project involving live animals in experimental procedures shall not be granted without a positive ethical review.

The ethical review process requires from experimenters a prospective assessment of the severity of the procedure (Article 15, Directive 2010/63/EU), which may be either “non-recovery,” “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” In addition, Article 54 on reporting requires that for the purpose of statistical information, the actual severity of the pain, suffering, distress, or lasting harm experienced by the animal must be reported. The actual severity of any procedure may be different from the prospective assessment or the prediction of severity made at the time of the project evaluation, but in all cases, it will be a key consideration in determining whether an animal can be reused in further procedures (Article 16, Directive 2010/63/EU).

The new European legislation has also implemented changes in the organization of the institutions in charge of animal welfare in the member states. In each establishment, a local animal welfare body (AWB) is created that shall include at least one person responsible for the welfare and care of the animals and an identified user, a scientist. The AWB is principally in charge of following the development and outcome of research projects, establishing and reviewing operational procedures such as monitoring or reporting, and advising the staff dealing with animals on matters related to the welfare of animals, their acquisition, accommodation, and care. Importantly, the AWB shall be in touch with a designated veterinarian with expertise in laboratory animal medicine (or a suitably qualified expert where more appropriate). In each member state, a competent authority is designated to be in charge of delivering an authorization for the project and for carrying out regular inspections. If not already in place, governmental agencies or advisory committees are created to monitor practices of animal use in research, to gather any elements that may contribute to the further implementation of the requirement of replacement, reduction, and refinement. For instance, in the UK, the Animal Procedures Committee created after the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (ASPA)7 and charged with advising the British Home Secretary on matters related to animal research is currently being replaced by an Animals in Science Committee.8 In France, the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche is now in charge of granting the authorization of projects involving animals. All experimenters are therefore advised to identify and become acquainted with the various authorities and other entities as well as their missions and responsibilities.

In the USA, the Animal Welfare Act (AWA)9 signed into law in 1966 and enforced by the Animal Care Agency of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) establishes the minimum acceptable standard and sets the requirements for the conduct and control of the use of animals in research. In its latest version, the AWA is a reference for all other laws, policies, and guidelines for animal care and use (e.g., Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare and National Institute of Health, 2002)). Useful resources derived from the AWA can be found in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals et al. 2011)10 and the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (Committee on Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research et al. 2003).

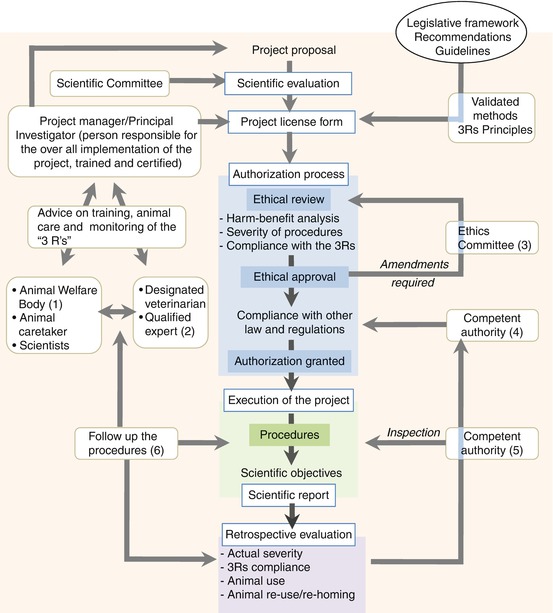

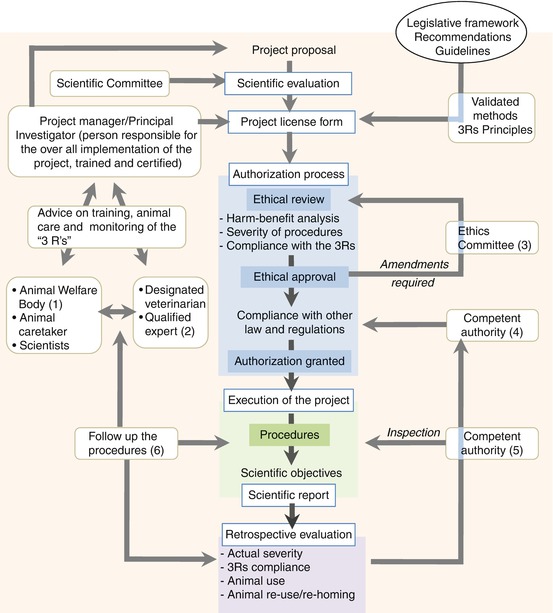

Legislative frameworks in most countries are the result of large-scale consultations of committees composed of representatives from academia, research organizations, veterinarians, as well as legal and ethical specialists and representatives of animal welfare organizations. Whether or not the research will find an outreach, all studies involving animals are now subject to a higher scrutiny prior to their beginning to ensure their necessity, proper justification, and adequate environmental and material context and design for their conduct, with an increasing attention on their compliance with the 3R principles (Fig. 1.1). For this purpose, most countries have introduced simplified administrative procedures through which investigators can obtain an agreement or license to perform animal research. Rather than a burden, this process should be seen as a step in the implementation of the 3Rs. Indeed, the submission of an animal protocol to an Animal Care Committee or equivalent authority represents a unique opportunity to thoroughly think about ways to reduce the number of animals used, to minimize animal pain and distress, and to consider alternative approaches.

Fig. 1.1

Flowchart for the implementation of a project

Inspired by the European Directive 2010/63/UE (January 1, 2013), this flowchart may apply to countries outside the European Union with adequate transposition. The apparent complexity of the flow chart is representative of the higher scrutiny applied to research or teaching projects that use live animals. (1) According to the last Directive, a local animal welfare body (AWB) is created in each establishment to work as close as possible with scientists. The AWB is roughly equivalent to an IACUC except that it is not in charge of the ethical review, a task usually assigned to a distinct Ethics Committee. (2) The designated veterinarian or qualified expert is a person with advisory duties regarding the well-being and treatment of the animals. (3) Ethics Committees are usually composed of at least a veterinarian, an animal caretaker (zootechnician), scientists, and a nonscientist. (4) A competent authority means an authority or body designated by a member state to deliver project authorizations and to carry out additional obligations arising from the latest Directive. Note that member states may designate bodies other than public authorities for the implementation of specific tasks. (5) The authority in charge of the inspection can be distinct from the authority that grants authorizations for the project, although both entities may be affiliated with the same governmental agency or ministry. (6) The follow-up of the conduct of the project notably includes the maintenance of records for each animal (see example in Appendix 2), with a daily monitoring of the health status, pain and distress (Appendix 4), and, if needed, the report of abnormalities (Appendix 1).

Licensing requirements may imply three types of licenses, an individual license for the investigator, another for the research facility that must also comply with the guidelines set forth by law, and one for the actual project that includes experiments on live animals. The following part of this chapter deals with the latter and lists the items commonly found in protocol/project license forms that are submitted to IACUCs or equivalent authorities.

1.2 Preparing a License Protocol Involving Stereotaxic Surgery

As a preamble, we would like to mention that a veterinarian should be involved in the development of an animal protocol. In the USA, according to the Animal Welfare Act and regulations (AWRs), a veterinarian must be consulted for any procedure that may cause more than momentary or slight pain or distress (AWR 2.31(d)(1)(iv)(B)). Such veterinary input, preferably before the protocol is submitted to a committee, can often simplify protocol review and shorten the approval process.

1.2.1 Prospective Assessment of Pain and Distress

Most project license forms require a prospective assessment of the severity of the procedure (Article 15, Directive 2010/63/EU). Stereotaxic surgeries in rodents are typically procedures that may cause more than momentary or slight pain. As such, they should only be performed with appropriate sedation, anesthesia and analgesia. In general, surgical or other painful procedures are not permitted on unanesthetized animals paralyzed by chemical agents. Whether the surgery is included in a survival procedure or is a terminal one, the rank of pain/severity will be the same. In the USA, both survival and non-survival procedures refer to the same USDA11 category D: animals used for teaching, research, experiments, testing, or surgery that will involve accompanying pain or distress and for which appropriate anesthetic, analgesic, or tranquilizing drugs will be used.12 In Europe, procedures are now classified as “non-recovery,” “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” The assignment of a severity degree shall be based on the most severe effects likely to be experienced by an individual animal after applying all appropriate refinement techniques. A procedure that includes a single stereotaxic surgery with a craniotomy should be ranked “moderate” (surgery under general anesthesia and appropriate analgesia, associated with postsurgical pain, suffering, or impairment of general condition (Section III of Annex VIII, Directive 2010/63/EU)). If the surgery is expected to result in severe or in moderate but persistent postoperative pain, suffering, or distress or is likely to cause severe impairment of the well-being of the animal, the procedure shall be classified as “severe” (equivalent USDA Category E13). For example, this can be the case if anesthetic, analgesic, or tranquilizing agents adversely affect the procedure and its results or interpretation and, therefore, cannot be used. For such procedures, the withholding of analgesia, anesthesia, or other treatment to alleviate pain/distress will have to be scientifically justified: in particular, the experimenter must provide the methods or means used to determine that pain and/or distress relief would interfere with the results. Note that for such severe/category E procedures, federal/state/local laws or policies may require separate declarations/forms and a systematic retrospective report.

Besides surgical pain, stereotaxic surgeries like other invasive techniques can induce transitory or even permanent functional damage or handicap. Depending upon the target area, or the way chosen to reach it, functional damage may be created by the sole introduction of a foreign object into the brain. To some extent, such damage can often be anticipated. For instance, if the procedure aims to lesion a brain area involved in motor control, a functional consequence should be expected that would affect locomotion or movement coordination and therefore compromise the animal’s well-being. For instance, neurotoxin lesioning of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra by 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) in rats (Schwarting and Huston 1996a, b; Kirik et al. 1998) induces a postural asymmetry and a unilateral akinesia when performed unilaterally. Partial or complete lesions are often accompanied by a spontaneous or induced sensitization of locomotor activity that can acutely or chronically affect the animal’s ability to eat, drink, and behave normally (Ungerstedt 1971). In such cases, adequate postoperative care procedures such as manual feeding can be required until the animal recovers its autonomy and a complete restoration of its behavioral repertoire. In a new project, a preliminary study with few animals can be included to tentatively determine if the procedure can cause a potential handicap.

In general, only one major survival surgery (i.e., having the potential for producing a permanent handicap for an animal expected to recover from surgery) may be performed per animal. If multiple survival procedures are essential parts of the project, experimenters are expected to provide a thorough justification and to describe the chronology of the multiple surgeries, how they are interrelated, and why they are necessary to achieve the scientific objective. Here again, cumulative pain, distress, or functional deficit that may result from the succession of procedures should also be detailed.

When assessing a level of pain and distress prior to an experiment, the entire lifetime experience of the animal should be considered, not just the animal’s experience during the stereotaxic surgery. It is therefore crucial to draw attention to the other factors that can also affect the animal’s well-being, such as transportation, housing, feeding and handling, and individual history if the animal has already been used in previous experiments. Procedures or treatments that precede the surgery (e.g., operant conditioning, irradiation, food/drink restriction, environmental distress, forced exercise, disease conditions, exposure to predator scents, and excessive noise) are other factors to consider. One needs to identify as many potential sources of pain and distress as possible, their intensity, and duration. In addition to the gestures performed during the surgery itself, and among other sources, incorrect tissue manipulation, inexperience of the experimenter, inadequate postoperative care, or insufficient acclimatization of the animals are potential sources of pain or distress. Furthermore, the phenotype, particularly in genetically modified animals (transgenic, knockout, knockin, floxed, cloned, or otherwise genetically modified strain) should not be neglected. For instance, some rat or mouse strains can be prone to seizures, and additional complications may arise from this condition. Listing all potential sources of pain or distress in the experimental model will not only help in the prospective assessment of pain/distress but also serve to define additional gestures and care of the subjects that will be proposed to the committee and performed by the collaborators of the study and the animal caretaker.

1.2.2 Measures to Alleviate Pain and Distress

After assessing the level of pain and distress in their models, experimenters are asked to thoroughly describe the methods and means used to monitor and to alleviate them.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree