Chapter 1 Rehabilitation in practice

how this book can help you to help your patients

Introduction

As McLellan wrote in 1997, rehabilitation is more akin to the active process of education than it is to the traditionally more passive concept of treatment. He defined rehabilitation as:

Rehabilitation: The key skills

The Brain Injury Association of Queensland (2009) highlights the ‘unique role and skills that neurological physiotherapists offer’. They argue that, while ‘vitally concerned with movement’, like all physiotherapists, the neurological specialists’ interventions may be ‘predominantly in teaching and training’ their clients. Developing skills, of course, requires extensive (hands on) practice, though many authors discuss the rehabilitation therapists’ requisite skills throughout this textbook, especially:

Rehabilitation: The knowledge base

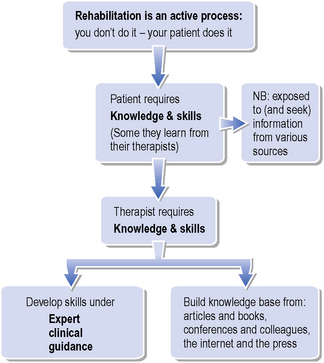

Coupled with good practical opportunities to learn and hone one’s skills under the guidance of clinical experts, this book will provide beginners in rehabilitation with many options for the management of patients. Students of rehabilitation (at any level) would do well to reflect on their own experiences as learners, as they evolve into knowledgeable and skilled professionals capable of contributing to their patients’ rehabilitation (see Figure 1.1).This book will provide students of rehabilitation with an explanation of the theories, tools and techniques that underpin rehabilitation in practice. Recently, Lennon and Bassile (2009) identified eight guiding principles for neurological physiotherapy. Sheila Lennon discusses all eight principles in Chapter 11 of this textbook and the reader will find that many of the other chapters also address these topics. In particular, four of these principles run throughout this textbook, illustrating their significance in current rehabilitation management:

Therapists moving into rehabilitation today are entering a field in which the knowledge base is expanding as the quality of studies improves. In 2002, Moseley et al. surveyed a physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro) and found ‘a significant body’ of high-level evidence (randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews) for all areas of physiotherapy. They further concluded that there remains scope for improving not just the conduct, but also the reporting of trials. These are the same conclusions that they reached in an earlier (Moseley et al., 2000) analysis that was focused specifically on neurological physiotherapy.

How to make the most of this book

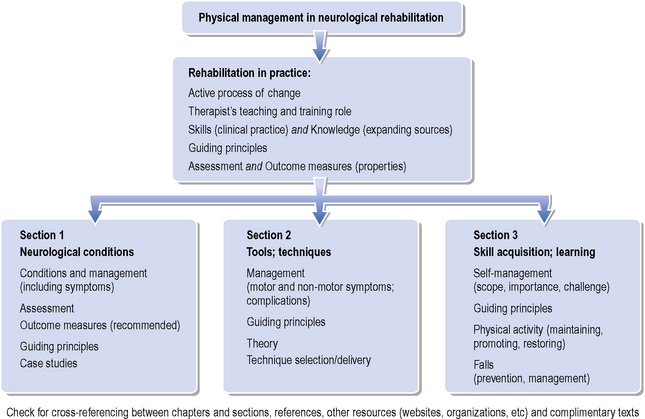

The book has three complementary sections, which, when read together with this chapter, offer a comprehensive insight into the challenges of rehabilitation (Figure 1.2). For example, practitioners seeking information about the return of functional mobility after stroke will find relevant details in the chapters on Stroke (Ch. 2 in Section 1), abnormal movement (Ch. 14 in Section 2) and activity and falls (Chs 18 & 20 in Section 3).

All chapters are heavily referenced, with pointers toward further resources and reading. This book is complimented by the Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy (Lennon & Stokes, 2009), which covers several other topics in detail, including:

Neurological conditions

Section 1 of this textbook contains chapters devoted to conditions that form the basis of neurological rehabilitation in practice. It is important to understand how variable the presentation and progression of neurological disorders can be. As De Souza and Bates emphasize in Chapter 5, for example, multiple sclerosis (MS) can mean anything from a mild and temporary focal deficit to a severe permanent disability of rapid onset. Whether a condition is common in the typical caseload (e.g. acquired brain damage, MS, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, stroke) or relatively rare (e.g. Huntingdon’s disease, motorneurone disease, muscle disorders, polyneuropathies), the authors have gathered as much up-to-date literature as possible in each case on:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree