Fig. 45.1

Patient #4 from the original reported series of RBD cases in 1986 [2] demonstrates a “home remedy” he resorted to using in desperation to prevent himself from leaping or falling out of bed and injuring himself. He wore a belt around his pajamas and then tied a rope around the belt on one end while tying the other end of the rope around the headboard of the bed. He engaged in this bedtime tethering ritual every night for 5 years before finding out about RBD in a news report and then presenting for evaluation at the sleep center

Table 45.1 lists descriptions of sleeping and living with RBD by a group of 26 patients and their spouses that signal the dangers of sleeping with RBD [5]. Extreme force can be generated in RBD that rapidly produces life-threatening situations. The wives were convinced that their husbands were fully asleep while having prominent, excessive body movements throughout the night: “He is sleeping and his body is in motion” (p. 132). The assumption often expressed by patients and spouses was that RBD was caused by work stress that would resolve with retirement turned out to be false, much to their chagrin. Another common assumption was that RBD was “part of getting old” and “it simply became routine,” [5] (p. 125); these couples became resigned to live with this new late-life “normality”—until they heard about RBD and its successful therapy, usually from media reports.

Table 45.1

RBD behaviors causing imminent danger: patient and spouse commentsa

A. Comments by RBD Patients | |

|---|---|

1 | “It seems that I am extra strong when I am sleeping.” (p. 142) |

2 | “I ran right smack into the wall, an animal was chasing me. I think it was a big black dog.” (p. 157) |

3 | “And the last time that happened, I didn’t remember the dream because I knocked myself out.” (p. 149) |

4 | “I thought I was wrestling someone and I had her by the head.” (p. 136) |

5 | “Pounding through the curlers into her head.” (p. 157) |

6 | “What scares me is what a catastrophe that would be to wake up and find that I had broken her neck.” (p. 137) |

7 | “I have hit her in the back too, and she has had a couple of (vertebral) disc operations.” (p. 143) |

8 | “One night I woke up as I was beating the hell out of her pillow…that’s when I realized that I had a problem.” (p. 106) |

9 | “Just recently, I rammed into her pelvis with my head…during a dream.” (p. 93) |

B. Comments by the Wives | |

1 | “It’s amazing. You should see the energy behind that activity, oh, it’s unreal.”(p. 107) |

2 | “He literally just kind of flew out of bed and landed on the floor with tremendous strength” (p. 53) |

3 | “It almost seems like a force picks him up.” (p. 130) |

4 | “His legs go so fast, just like he’s running” (p. 155) |

5 | “It is his kicking, violent kicking, his feet are just like giant hammers when they hit you over and over again.” (p. 73) |

6 | “I felt that kick on the ankle for two months afterwards.” (p. 82) |

7 | “That’s the reason we got the waterbed—because he was wrecking his hands on the wooden bed.” (p. 111) |

8 | “Oh, yes, there were always bloody sheets.” (p. 105) |

9 | “Roaring like a wounded wild animal: he roared, he crouched, he punched.” (p. 75) |

10 | “I told him I‘d have one devil of a time explaining how I got a broken arm in bed with both of us asleep.” (p. 126) |

11 | “What happens to people like my husband who don’t get diagnosed? Do they kill their wives in these experiences, do we know?” (p. 139) |

Historical Background of RBD: 1966–1985

Various polysomnography (PSG) and clinical aspects of human RBD were described since 1966 by investigators from Europe, Japan, and North America, almost exclusively in neurologic settings, as reviewed [2, 6, 7]. Two groups of pioneering investigators should be recognized [6]: (i) Passouant et al. from France in 1972 first identified a dissociated state of REM sleep with tonic muscle activity induced by tricyclic antidepressant medication. (ii) Tachibana et al. from Japan in 1975 named “stage 1-REM sleep” as a peculiar sleep stage characterized by muscle tone during an REM sleep-like state that emerged during acute psychoses related to alcohol and meprobamate abuse. Also, clomipramine therapy of cataplexy in a group of patients with narcolepsy commonly produced RWA in a study from 1976 by Guilleminault et al. [8]. Elements of both acute and chronic RBD manifesting with “oneirism” were represented in the early literature, along with RWA without clinical correlates: Delirium Tremens (DTs) and other sedative and narcotic withdrawal states, anticholinergic use, spinocerebellar and other brainstem neurodegenerative disorders ; the “REM rebound and REM intrusion” theories were proposed and discussed in many of these early reports. The 1986 report in SLEEP firmly established that RBD is a distinct parasomnia, which occurs during unequivocal REM sleep, and which can be idiopathic or symptomatic of a neurologic disorder [2] . Although there is a variable loss of the customary, generalized muscle paralysis of REM sleep, all other major features of REM sleep remain intact in RBD, such as REM latency, REM percent of total sleep time, number of REM periods, and REM/nonrapid eye movement (NREM) cycling. PSG monitoring of these patients established that RBD did not emerge from a “stage-1 REM sleep” that was separate from REM sleep, nor did RBD emerge from a poorly defined variant of REM sleep, or from an unknown or “peculiar” stage of sleep, or during “delirious” awakenings from sleep—all of which had been mentioned in the literature. The 1986 SLEEP report also called attention to generalized motor dyscontrol across REM and NREM sleep, manifesting as increased muscle tone and/or excessive phasic muscle twitching in REM sleep, along with periodic limb movements and excessive nonperiodic limb twitching in NREM sleep [2]. A lengthy prodrome in RBD was also described; a characteristic dream disturbance was identified; and a successful treatment with bedtime clonazepam was empirically discovered .

Animal Models of RBD

An experimental animal model of RBD was first reported in 1965 by Jouvet and Delorme from the Claude Bernard University in Lyons, France [6, 9], which was produced by brainstem lesions in the peri-locus ceruleus area that released a spectrum of “oneiric” behaviors during REM sleep (called paradoxical sleep and active sleep by basic scientists). These oneiric behaviors in cats closely match the repertoire of RBD behaviors in humans. Research on animal models of RBD (that now include cats, rats (brainstem lesion models), and mice (transgenic mouse model with impaired GABA and glycine transmission) [6, 9–11] and on the neuroanatomy and neurochemistry subserving REM-atonia and the phasic motor system in REM sleep has progressed considerably in recent years .

Ramaligam et al. [12] summarize research from the past five decades on the neural circuitry regulating REM-atonia, and identify REM-active glutamatergic neurons in the pontine sublaterodorsal (SLD) nucleus as being a critical area, as descending projections from the SLD activate neurons in the ventromedial medulla (VMM), from where inhibitory descending projections to the spinal cord ultimately produce the REM atonia . Damage to the SLD appears critical for triggering RBD in humans, based on neuropathological findings in humans with neurodegenerative disorders . Luppi et al. focus on the potential roles of brainstem glutamate, GABA, and glycine dysfunction in the pathophysiology of RBD, and propose alternative explanations for RBD apart from SLD damage [13]. A new study by Hsieh et al. [14] found that yet another brainstem region may be implicated in human RBD, involving GABA-B receptor mechanisms in the external cortex of the inferior colliculus. Therefore, REM sleep has an intrinsically programmed, brain-generated, active motor-inhibitory system, and not a passive withdrawal of motor activity. The atonia of REM sleep is briefly interrupted by excitatory inputs which produce the REMs and the muscle jerks and twitches characteristic of REM sleep.

All categories of behaviors found in human RBD are mirrored in an experimental animal model of RBD produced by pontine tegmental lesions [6, 9]. The pathophysiology of human RBD is presumed to correspond to the findings from an animal model of RBD in regard to interruption of the REM-atonia pathways and/or disinhibition of brainstem motor pattern generators .

Finally, naturally occurring, congenital, and adult-onset RBD in cats and dogs has been reported, with effective therapies being identified (as reviewed [5, p. 415–6], [6]). This reflects an intriguing animal–human reciprocity, as the experimental animal model of RBD facilitated the understanding of human RBD and its effective therapy with clonazepam , which in turn facilitated awareness of naturally occurring RBD in dogs and cats and use of effective therapy with clonazepam.

Early Historical Milestones of RBD: 1986–1997

Among the ten patients in the original series, five had diverse neurologic disorders etiologically linked with RBD, and five were idiopathic [2, 3]. As a larger group of idiopathic RBD (iRBD) patients was gathered and followed longitudinally at our center, a surprisingly strong and specific association with eventual parkinsonism and dementia became apparent [20, 23], which has spurred a major, growing, multinational research effort [24, 25], including the formation of the International RBD Study Group (IRBD-SG) [10]. Many other important clinical associations with RBD have been identified, such as the strong link with narcolepsy [19, 26]. RBD is situated at a strategic crossroad of sleep medicine, neurology, and the neurosciences. The literature on RBD has continued to grow exponentially in breadth and depth [27]. RBD publications have now exceeded 100 per year. The “RBD odyssey” [28] exemplifies the strong cross-linkage between the basic science underlying REM sleep and the clinical features of RBD, and the close correspondences between animal models of RBD and clinical RBD. Table 45.2 presents early RBD historical milestones [2, 3, 20, 19, 15–18, 21, 22], with elaboration below.

Table 45.2

Early historical milestones in RBDa

1986–1987 | |

1989 | RBD in the differential diagnosis of sleep-related injury [15] |

1990 | Forensic aspects of RBD [16] |

1991 | Status dissociatus [17] |

1992 | Medication-induced RBD [18] |

1992 | Narcolepsy-RBD [19] |

1996 | Delayed emergence of parkinsonism in RBD [20] |

1996 | Association of RBD with specific HLA haplotypes [21] |

1997 | Parasomnia overlap disorder [22] |

Clinical and PSG Findings in RBD

There are two essential diagnostic hallmarks of RBD, involving clinical and PSG components [4]. The clinical component involves either (i) a history of abnormal sleep-related behaviors that are often dream-enacting behaviors, and/or emerge during the second half of the sleep cycle when REM sleep predominates compared to the first half of the sleep cycle, and/or (ii) abnormal REM sleep behaviors documented during video-PSG in a sleep laboratory, which are often manifestations of dream enactment. It is important to note that the diagnosis of RBD does not require dream enactment [4], since about 30 % of reported RBD cases in the world literature do not have dream enactment (usually in patients with neurodegenerative disorders, including dementia) , as reviewed [29]. The PSG hallmark of RBD consists of electromyographic (EMG) abnormalities during REM sleep, referred to as “loss of REM-atonia,” or “RWA,” featuring increased muscle tone and/or increased phasic muscle twitching [4]. Figures 45.2, 45.3, 45.4a, b depict examples of PSG findings in RBD.

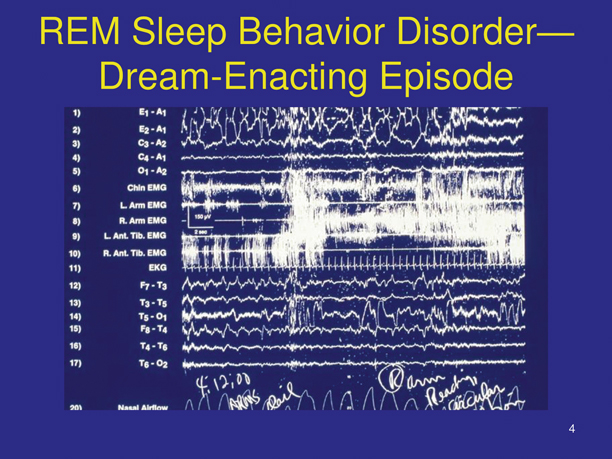

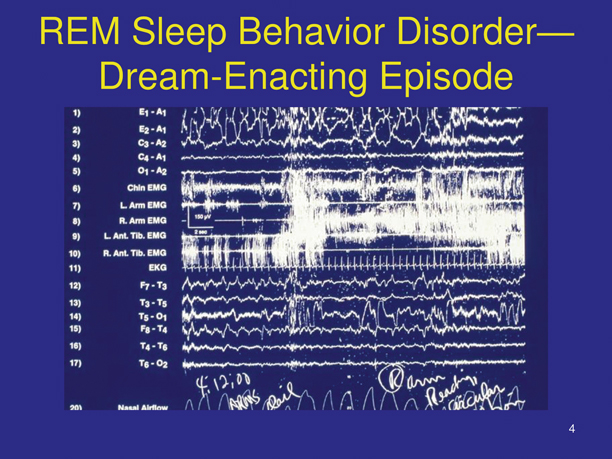

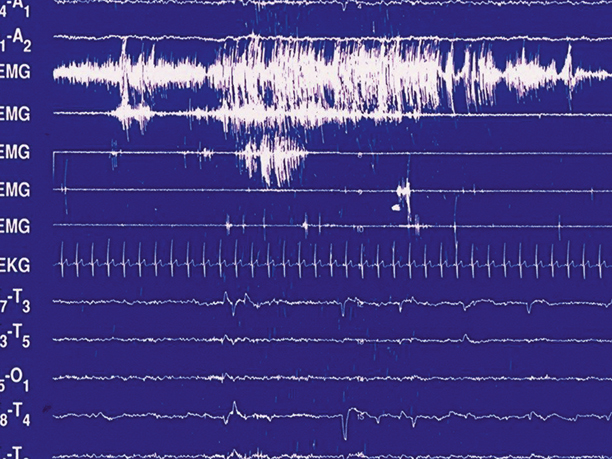

Fig. 45.2

Dream-enacting episode during REM sleep in a 62-year-old man with RBD. As the sleep technologist noted the episode on the PSG tracing, the man was dreaming that he was on a boat on Lake Superior, by Duluth, Minnesota. The boat was rocking violently in the water, and he was on the main deck urgently reaching for the handrail with his right hand in circular motions to grab hold of the handrail and stabilize himself—and avoid being thrown down into the hold of the ship where menacing skeletons were beckoning at him. When he woke up, he instantly became alert and oriented, and relayed the dream to the technologist, who acknowledged that the observed behavior closely matched the dream sequence, an example of “isomorphism.”There is complete obliteration of “REM-atonia” in this tracing, with continuous increase of chin muscle tone, and tremendous phasic EMG activation of the chin and both upper and lower extremities. Despite the intense, generalized phasic motor activation and concomitant behavioral release, the EKG rate remains constant, without acceleration, which is typical of RBD and in sharp contrast to the disorders of arousal from slow-wave sleep.

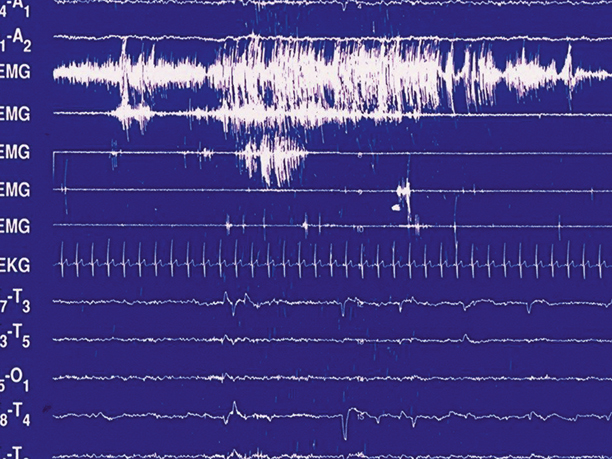

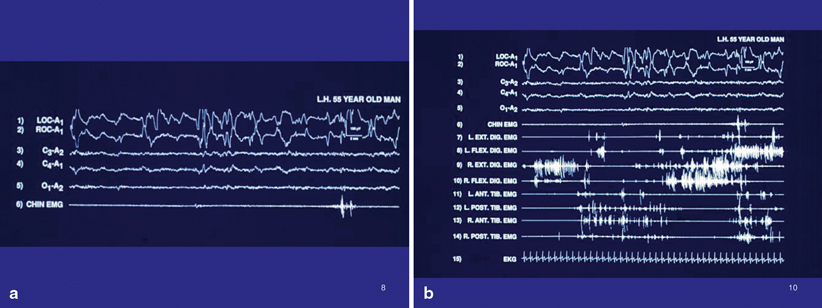

Fig. 45.3

Same-patient and same-night PSG as in Fig. 45.2. This tracing during REM sleep shows REMs in the top two channels, nearly complete loss of REM-atonia, with brief restoration of normal REM-atonia in the chin EMG towards the end of the tracing. The upper extremities show robust phasic EMG twitching, in sharp contrast to the virtual lack of phasic EMG activity in the lower extremities, thus calling attention to the recommended EMG montage in evaluating for RBD that should include bilateral upper extremity EMG monitoring, besides lower extremity and chin EMG monitoring

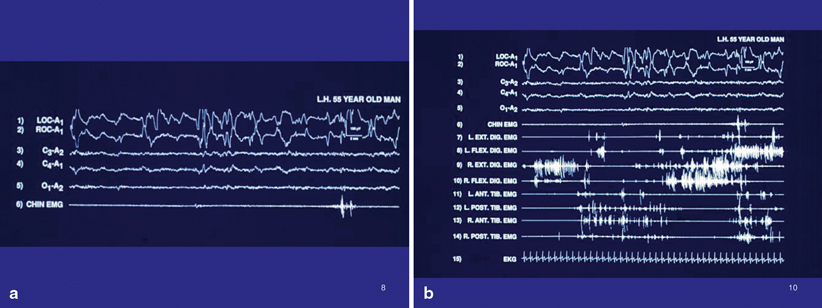

Fig. 45.4

a PSG tracing of RBD, with REMs, an activated EEG, and continuously preserved REM-atonia, with normal, brief phasic twitching of the chin EMG. b Expanded montage. Note the excessive phasic EMG twitching of opposing flexor and extensor muscles in both the upper and lower extremities, in the context of preserved REM-atonia shown by the chin EMG. This exemplifies the need for an expanded EMG montage in the evaluation of RBD. Also, the phasic coactivation of opposing muscle groups, viz. right flexor and right extensor digitorum muscles (robust in this tracing), is a common finding during REM sleep in RBD, which ordinarily is not present in wakefulness, since it would be completely dysfunctional (usually there is reciprocal inhibition of an opposing muscle group when one muscle group is activated for a functional purpose). This tracing exemplifies a subtype of motor dyscontrol in RBD in which there is excessive extremity phasic EMG twitching with preserved background atonia shown in the chin EMG

RBD represents how one of the defining features of mammalian REM sleep, viz. generalized skeletal muscle atonia—“REM-atonia”—can be partially or completely eliminated, resulting in a major clinical disorder. RBD is the only parasomnia in the ICSD-2 [4] and ICSD-3 that requires PSG confirmation. There are three reasons for this requirement: first, the core EMG abnormalities of RBD are present every night (given a sufficient amount of REM sleep); second, RBD is not the only dream-enacting disorder in adults, and so objective confirmation is highly desirable; third, given the strong probability of future parkinsonism in males ≥ 50 years of age initially diagnosed with idiopathic RBD, it is imperative to diagnose RBD objectively so that affected males (and their families) can be properly informed and be encouraged to plan for the future accordingly.

Some patients almost exclusively have arm and hand behaviors during REM sleep, indicating the need for both upper and lower extremity EMG monitoring in fully evaluating for RBD. Some patients preserve most of their REM-atonia, but have excessive EMG twitching during REM sleep. Autonomic nervous system activation (viz. tachycardia) is uncommon during REM sleep motor activation in RBD, in contrast to the disorders of arousal. Periodic limb movements (PLMs) during NREM and REM sleep are very common with RBD, and may disturb the sleep of the bed partner. These PLMs are rarely associated with electroencephalogram (EEG) signs of arousal. Increased percentages of slow-wave sleep and increased delta power in RBD have been found in controlled and uncontrolled studies, but this can be a highly variable finding in RBD, depending on the clinical population. Sleep architecture and the customary cycling among REM and NREM sleep stages are usually preserved in RBD, although some patients show a shift toward N1 sleep (particularly in neurodegenerative disorders) .

There has been an advance over time from the qualitative determination of RWA to a more rigorous, quantitative determination of RWA, to assist with the diagnosis of RBD . The most current evidence-based objective data provide the following guidelines for detecting RWA and guidelines for their interpretation supporting the diagnosis of RBD:

1.

RWA is supported by the PSG findings of either: (i) tonic chin EMG activity in ≥ 30 % of REM sleep; or (ii) phasic chin EMG activity in ≥ 15 % REM sleep, scored in 20 s epochs [30].

2.

Any (tonic/phasic) chin EMG activity combined with bilateral phasic activity of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscles in ≥ 27 % of REM sleep, scored in 30 s epochs [31].

3.

Automated quantification methods have been developed for generating the “REM sleep atonia index” with scores ranging from 0 (complete loss of REM-atonia) to 1 (complete preservation of REM-atonia); cut-score for RSWA is atonia index < 0.9 [32].

As demonstrated by RBD, REM-atonia serves an important protective function, as it allows the dreaming human or other mammal to engage in a full spectrum of physically active dreams while being simultaneously paralyzed and thus unable to actually move while having active dreams. A person with RBD moves with eyes closed and with complete unawareness of the actual surroundings—a highly vulnerable state for the dreamer [5, 15, 16]. The clinical manifestation of RBD is usually (but not necessarily) dream-enacting behavior. Injury to oneself or bed partner is common in RBD. Typically, at the end of an episode, the individual awakens quickly, becomes rapidly alert, and reports a dream with a coherent story, with the dream action corresponding to the observed sleep behaviors. This phenomenon is called “isomorphism” with examples provided in the previous section. After awakenings from RBD episodes, behavior and social interactions are appropriate, mitigating against either an NREM sleep phenomenon, delirious state, or an ictal phenomenon.

Sleep and dream-related behaviors reported by history and documented during video PSG include both violent and (less commonly) nonviolent and even pleasant behaviors [6, 33]: talking, smiling, laughing, singing, whistling, shouting, swearing profanities, crying, chewing, gesturing, reaching, grabbing, arm flailing, clapping, slapping, punching, kicking, sitting up, looking around, leaping from bed, crawling, running, dancing, and searching for a treasure or other objects. Walking, however, is quite uncommon with RBD, and leaving the room is especially rare, and probably accidental. Rarely there can be smoking a fictive cigarette; masturbation-like behavior; pelvic thrusting; and mimics of eating, drinking, urinating, and defecating. Since the person is attending to the dream action with eyes closed, and not attending to the actual environment with eyes open, this is a major reason for the high rate of injury in RBD, besides the aggressive and violent behaviors.

Sleep talking with RBD runs the spectrum from short and garbled to long-winded and clearly articulated speech. Angry speech with shouting and profanity, and also humorous speech with laughter, can emerge.

One recent study found that of 14 RBD patients with repeated laughing during REM sleep documented by video-PSG, 9 were clinically depressed during the daytime, indicating a state-dependent dissociation between waking versus REM sleep emotional expression in RBD [34].

As RBD occurs during REM sleep, it usually appears at least 90 min after sleep onset, unless there is a coexisting narcolepsy, in that case RBD can emerge shortly after sleep onset during a sleep-onset REM period (SOREMP). Although irregular jerking of the limbs may occur nightly (comprising the “minimal RBD syndrome”), the major behavioral episodes appear intermittently with a frequency minimum of usually once every 1–2 weeks up to a maximum of four times nightly on ten consecutive nights [5, 6].

Chronic RBD may be preceded by a lengthy prodrome (in one series it was 25 %) consisting of prominent limb and body movements during sleep and new-onset sleep talking [35]. RBD is usually a chronic progressive disorder, with increasing complexity, intensity, and frequency of expressed behaviors. Spontaneous remissions are very rare. RBD, however, may subside considerably during the later stages of an underlying neurodegenerative disorder. Although the prevalence of RBD is not known, surveys have estimated a prevalence of 0.38–0.5 % [4]. The prevalence of RBD in older adults is probably considerably higher [36].

Most patients with RBD who present for clinical evaluation, complain of sleep injury and rarely of sleep disruption. Daytime tiredness or sleepiness is uncommon, unless narcolepsy is also present, or there is coexisting obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). There is typically no history of irritable, aggressive, or violent behavior during the day. One study of consecutive referrals to a sleep center found that the majority of patients diagnosed with RBD reported symptoms on specific questioning only, underlining the importance of eliciting a comprehensive history for the diagnosis of RBD [37].

Documented injuries to the patient and bed partner resulting from RBD include: bruises; subdural hematomas; lacerations (including arteries, nerves, tendons); fractures (including high cervical fractures); dislocations, sprains, abrasions, rug burns; tooth chipping; scalp injury from hair pulling. The published cases of RBD (as of 2010 [38]), associated with potentially lethal behaviors include: choking/headlock (n = 22–24), diving from bed (n = 10), defenestration (n = 7), and punching a pregnant bed partner (n = 2). The potential for injury to self or bed partner raises important and challenging clinical issues (such as in ICU settings [39, 40]) and forensic medicine issues [16], including “parasomnia pseudo-suicide” [41] and inadvertent murder; guidelines have been developed to assist experts in forensic parasomnia cases [16, 42].

There has only been one reported case of marital separation or divorce related to RBD, in a recently married young adult with narcolepsy-RBD [43], this probably reflects the many decades of marriage prior to the onset of typical RBD, and so the wives of men with RBD understand that the violent dream-enacting behaviors are completely discordant from the usual pleasant-waking personality [5]. Nevertheless, RBD can pose serious risks to a marriage. A recently married, young adult Taiwanese woman with RBD attempted suicide because her husband would not sleep with her at night, since he complained that her RBD disrupted his sleep excessively and compromised his work productivity [44]. Fortunately, once her RBD was diagnosed and effectively treated with clonazepam, the husband resumed sleeping in their conjugal bed, and their marriage was preserved.

Finally, there is an acute form of RBD that emerges during intense REM sleep rebound states, such as during withdrawal from alcohol and sedative–hypnotic agents, with certain medication use, drug intoxication, or relapsing multiple sclerosis [45].

RBD and Dreaming

In typical RBD affecting middle-aged and older men, the enacted dreams are often vivid and action-filled with unpleasant (“nightmarish”) scenarios involving confrontation, aggression, and violence with unfamiliar people and animals, and the dreamer is rarely the instigator. In fact, the dreamer is often defending his wife in a dream while actually beating her in bed. There can also be culture-specific sports dreams, such as American football, Irish rugby, or Canadian ice hockey. Some patients experience recurrent dreams (with enactment) with presumed vestibular activation, involving spinning objects or angular motion with acceleration (e.g., a car speeding down a steep hill); other patients experience atonia suddenly intruding into their dream-enacting episodes, and fall down while dreaming of suddenly becoming stuck in mud or trapped in deep snow .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree