Essential Features

The RLS diagnosis depends entirely on clinical symptoms matching the four essential criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) workshop (

Table 15-1). The first criterion that defines the primary symptom of RLS is a strong urge to move the legs and can be termed a focal akathisia. This akathisia is often, but not always, accompanied by other disagreeable sensations or paresthesias usually involving a dynamic sensation located deep in the leg, not on the surface or in the skin. Any observable physical abnormality in the leg or changes in its appearance rarely if ever occur with these paresthesias. Subjects commonly report they are unable to describe the sensory disturbance but recognize it as unpleasant and, in a minority of cases, actually painful. The remaining three essential criteria indicate the conditions in which the RLS symptoms occur. Rest involving both decreased motor and mental activity engenders or worsens the symptoms. This quiescegenic feature depends upon both the duration and degree of rest for promoting symptom onset. Obversely, activity reduces the RLS symptoms. Walking or moving the legs produces an almost immediate relief from symptoms as long as the movement continues. Sometimes intense mental activity, such as arguing or playing an involving computer game, also significantly relieves the symptoms. The symptom relief lasts for variable amounts of time once the patient returns to resting, and there is no clear indication that the intensity or duration of the activity affects the subsequent duration of rest before symptoms recur. Finally, the symptoms have a strong circadian pattern, with symptoms occurring most prominently on the descending limb of the daily temperature curve during the late afternoon, evening, and night (

8). Symptoms decrease or disappear in the midmorning about 6 to 10 AM, only to reoccur the next evening or night. The quiescegenic and circadian features interact. The duration of time the patient can sit or lie still decreases as the day progresses. In mild cases, it may take as much as an hour or more of rest to engender the symptoms, which may not be severe enough to awaken the patient. Thus, if the patients falls asleep in <30 minutes, the symptoms will be experienced only during protracted periods of enforced rest in the afternoon or evening, such as when traveling or attending a performance or meeting. More severely affected patients, however, have trouble lying still long enough to fall asleep at night and, once asleep, may even wake up with the symptoms compelling them to get out of bed and walk for a while.

Features Supportive of the Diagnosis

Three features supportive of the diagnosis may guide clinical judgment in situations of diagnostic uncertainty (

Table 15-1). RLS, particularly when it starts early in life, frequently occurs in more than one member of a family. RLS in the family supports the diagnosis. Nearly all patients report reduced symptoms at least initially when treated with L-dopa or a dopamine agonist. When there is no such response, the diagnosis should be reconsidered. PLMS occur for about 80% to 90% of all RLS patients (

9) and, similarly, most RLS patients have periodic limb movements while lying resting awake, either during the sleep period or during a special suggested immobilization test (SIT) (

10). These movements represent the motor expression of the disorder and provide the only sign for the disorder. Their presence supports the diagnosis when other causes for the movements can be excluded; their absence makes the diagnosis unlikely.

Differential Diagnoses

Some conditions produce symptoms that mimic RLS and are commonly misdiagnosed as RLS. The most common is positional discomfort occurring from sitting or lying in a fixed position too long. This puts pressure on veins, nerves, or simply on the skin itself, producing a discomfort and a need to move to relieve the discomfort. The characteristic difference is that relief occurs with a simple change in body position without any persisting activity. RLS requires some degree of activity to reduce the symptoms after return to resting. Positional discomfort usually occurs only when sitting whereas RLS, in contrast, usually occurs whenever the patient is resting and thus should at least occasionally occur when lying down. The same considerations apply to the urge to move occurring with orthostatic hypotension (

11).

Pain from arthritis or other conditions can be circadian, worse at night, and, in some cases, brought on by rest and relieved by activity. Usually, unlike the RLS situation, the relief by activity does not occur almost immediately nor does it persist as long as the movement continues. The urge to move is usually more clearly secondary to the desire to relieve the pain; RLS patients desire to move to relieve a focused urge to move the leg, more than to relieve some other sensation associated with the leg.

Nocturnal leg cramps are sometimes confused with RLS. For these, a specific activity of stretching the affected muscle is usually required to produce relief; RLS patients may also stretch or tense muscles to reduce symptoms, but they find that almost any other leg activity also reduces symptoms.

Habitual or unconscious movements, such as foot tapping and sleep starts, can sometimes be confused with RLS, but these are automatic behaviors occurring without awareness of any urge to move. Inferring an urge to move the leg, based on an observation of movement occurring, differs from the clear awareness of the urge to move occurring with RLS. RLS patients may also have involuntary leg movements but, independent of the involuntary or unconscious movements, they have a conscious awareness of the akathisia focused on, and even appearing to stem from, the leg.

Neuroleptic-induced akathisia appears to be similar to RLS, and the differential diagnosis depends upon the history of medication use and response to discontinuing or changing the neuroleptic.

Neuropathies, anxiety, and moving toes and painful legs can at times be misdiagnosed as RLS. These generally do not involve a primary urge to move and are either not quiescegenic or circadian.

Objective Diagnostic Tests

RLS diagnosis relies on the clinical symptoms, but the occurrence of PLMS as a motor sign for the disorder provides strong support for the diagnosis. These periodic leg movements occur during sleep (PLMS) and also when awake lying down resting (PLMW). They are measured using electromyographic recordings from the anterior tibialis or using activity meters placed on the ankle. They occur every 5 to 90 seconds and may persist for several minutes. Each movement during sleep lasts 0.5 to 5.0 seconds, but during waking tends to be longer, lasting 0.5 to 10 seconds. More details for scoring these are provided in the last section of this chapter. In one study, PLMS > 7 per hour supported the diagnosis of RLS with an accuracy of 84%, but PLMW > 15 per hour during the nocturnal PSG provides much better support for the diagnosis, with an accuracy of 91% (

10). PLMW should always be scored when doing a PSG as a sign of RLS.

A specific test, the SIT, has been developed to evaluate the sensory and motor symptoms of RLS during a period of rest. The patient sits reclining in bed at about a 45-degree angle, with legs outstretched, without any cognitive or motor stimulation for 60 minutes. The patient is told to remain awake and to lie still without moving the legs unless the movement is needed to relieve RLS symptoms. The standard PSG recording is obtained without respiratory measures and, if sleep occurs, the patient is awakened. The patient provides a rating of the sensory discomfort in the legs on a 100-mm vertical bar using an electronic device placed conveniently at the bedside to minimize disturbance of the resting aspect of the SIT once every 5 minutes. The SIT is usually done in the hour before sleep onset. In one study, the diagnostic accuracy for PLM per hour >12 was 75%; the sensory score >11 mm was 88% (

10). It should be noted that the sensory score for leg discomfort on the SIT provides the only systematized assessment of the expression of the primary RLS symptom when provoked. While this makes it an interesting measure, it also makes it somewhat more prone to environmental and subject variation. Reporting sensory symptoms also interrupts somewhat the SIT, thereby reducing the provocative nature of the boredom with this test and possibly reducing the sensitivity of the SIT.

The best laboratory objective test was the PLMW during the nocturnal PSG; the second best was the sensory score during the SIT, but the PLMW during the SIT was a close third.

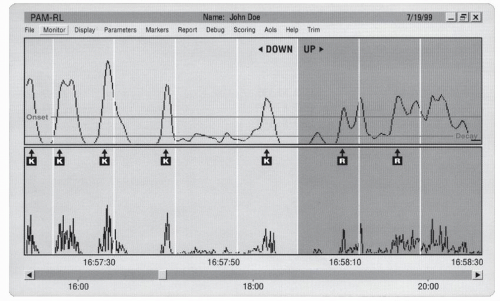

Activity meters presumably could also be used to measure PLMW and PLMS together over several nights and presumably, given the repeated nights, would have at least the same degree of accuracy as the PLMS and PLMW from the PSG on a single night. Recent advances in activity measures include a device developed by IM Systems in Baltimore and now available from Phillips-Respironics. It uses a three-dimensional sensor sampling the activity at 40 Hz and recording it at 10 Hz for up to 5 consecutive days. It also includes a position sensor that separates the movements into those occurring when the leg is in the lying position versus standing or sitting. Its software identifies the PLM and provides a summary of the PLM per hour, adjusted for the amount of time in each body position. Validation studies comparing this activity meter to the PLMS and PLMW in a mixture of RLS and insomnia patients showed that the measurement of PLM per hour was accurate within ± 2 (correlation seconds >0.90) (

12). (See

Fig. 15-1 for an example of the activity recording of leg movements for an RLS patient while awake resting.) For RLS, this device also measures the amount of lying the patient is able to do during the night. There is obvious appeal to an objective test that could be obtained in the home using a device that could be mailed to the patient. Moreover, PLM vary considerably night-to-night within a subject. A reasonably stable estimate of a subject’s PLM per hour of sleep requires, in general, recording for about 5 nights (

13).

Secondary Restless Legs Syndrome

RLS commonly occurs with end-stage renal disease, pregnancy, and iron deficiency and, for each of these conditions, RLS commonly starts and ends with the condition. RLS occurs in 20% to 70% of patients on dialysis, depending on the population (

14,

15), and has been associated with increased risk of mortality (

14). RLS symptoms disappeared in 1 to 21 days after a successful kidney transplant (

16). RLS occurs in about 20% to 30% of women during pregnancy, mostly in the third trimester (

17,

18,

19 and

20), and resolves for most, but not all, within a few days after delivery (

18,

20). The fact that RLS persisted after delivery raises the possibility that pregnancy may be a risk factor for its development. It occurs commonly in patients with iron deficiency and, for these patients, correction of the iron deficiency generally leads to remission or at least a significant reduction in the severity of the RLS symptoms.

The relationship between RLS and neuropathy remains unclear. While neuropathies have been reported to be surprisingly common among RLS patients (

21,

22), the best survey to date did not find a high prevalence of RLS among patients with neuropathy (

23). One comparison of types of neuropathy found RLS commonly occurred for patients

with Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease (CMT) type 1, but not CMT type 2, suggesting that RLS was associated or possibly secondary to neuropathy-disrupting sensory processing (

24).

Several conditions that compromise iron status have also been advanced as causing RLS, such as very frequent blood donations (

25), low-density lipoprotein apheresis (

26), rheumatoid arthritis (

27), and gastric surgery (

28). It seems likely that RLS results from the iron deficiency more than other aspects of these conditions.