Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome

Key Points

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is a relatively common disorder, sharing pathophysiologic features with a spectrum of disorders, including posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), drug-related arteriopathies, and others.

The clinical presentation of “thunderclap” headache is typical of this disorder, but not specific.

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is a group of diverse disorders characterized by acute onset, often with a thunderclap headache and an acute course of illness spanning 2 to 8 weeks during which complications of cerebral vasoconstriction may become clinically evident. About 40% of cases can be termed primary, that is, no known cause or precipitant, and about 60% have well-recognized antecedent risk factors. Within this entire group of disorders, an undefined dysregulation of arterial tone is a common feature, leading to significant overlap in clinical features with other disorders such as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). It is important to be familiar with the entity of RCVS as it is not as rare a condition as it was once considered. Furthermore, some of the features of RCVS can lend itself to being confused with primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS), a distinct condition with a very different prognosis and specific treatment requirements.

Background

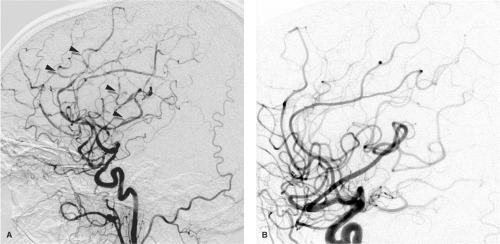

The recognition of RCVS as a distinct, although heterogeneous, group of related conditions has evolved over the past two decades. A paper in 1988 (1) by Call and Fleming drew attention to a group of patients presenting with sudden severe headaches and proceeding to variable patterns of cerebral ischemia associated with multivessel, scattered vasoconstriction of the circle of Willis and its major branches (Figs. 26-1–26-3). Over the years since then, many reports and case series of patients with disparate backgrounds have appeared, all of whom shared many features with the patients in the 1988 paper. These were variably described as having benign angiopathy of the central nervous system (CNS), postpartum angiopathy, migrainous vasospasm, drug-related CNS arteritis, pheochromocytoma-induced arteritis, hypertensive encephalopathy, or variants of PRES. The clinical, prognostic, and treatment similarities among all these groups, as distinct from patients with other conditions, particularly PACNS (see Chapter 27) and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, make the categorical labeling with RCVS useful and valid. Primary RCVS remains a diagnosis of exclusion, after other entities have been considered, but because this is not a rare phenomenon, and is in fact more common than PACNS, patients with primary RCVS need to be spared the more drastic immunosuppressive therapy warranted for PACNS. Thunderclap headache is not pathognomonic of RCVS, even in the absence of a cerebral aneurysm ruptured or otherwise. Entities such as intracranial dissection, ischemic stroke, acute hypertensive crisis, acute obstruction by a colloid cyst, or intracranial infection are all considered in the differential diagnosis initially (2).

Clinical Presentation of RCVS

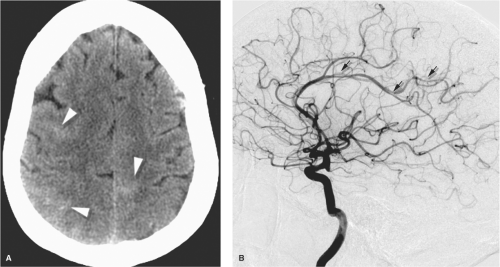

Several large case series of patients with RCVS report a consistent clinical appearance and course of this condition (3,4,5,6). Typically this condition is seen in its primary form, or with minimal risk factors, in middle-aged women (80%), while younger male patients have a greater likelihood of associated risk factors. Less commonly, the condition has been identified in children (7,8). The presentation is abrupt, most frequently with a thunderclap headache in 82% to 100% of patients, which may be recurrent during the first week. By the 2nd or 3rd week, neurologic complications of vasoconstriction declare themselves, and about 80% of patients develop brain lesions on MRI or CT. About 40% develop ischemic strokes usually in a watershed distribution and frequently with a pattern similar to that seen in PRES (9,10), subarachnoid hemorrhage 30% to 40%, lobar hemorrhage, cortical blindness (Anton’s syndrome), or seizure. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is normal except where xanthochromia from hemorrhage is to be expected. Segmental, multivessel irregularities with a “bead and string” appearance will be seen in the majority of patients on CTA or MRA, although the initial study may frequently be normal. In the published papers,

catheter angiography shows abnormalities in 100% of patients. About 80% of patients or more have a very favorable outcome, provided that severe complications of ischemic stroke are not present, and the condition runs its course within 6 to 12 weeks with complete normalization and reversal of imaging features of vasoconstriction.

catheter angiography shows abnormalities in 100% of patients. About 80% of patients or more have a very favorable outcome, provided that severe complications of ischemic stroke are not present, and the condition runs its course within 6 to 12 weeks with complete normalization and reversal of imaging features of vasoconstriction.

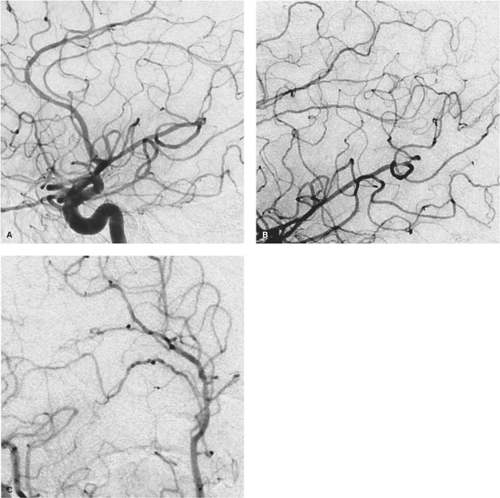

Figure 26-2. (A–C) Marijuana-related RCVS. A middle-aged patient with a long history of heavy marijuana use was admitted with headache and mental status changes. The angiogram of the right internal carotid artery (A, lateral view; B, magnification view; C, magnification oblique view) shows a more subtle appearance of RCVS than that seen in Figure 26-1, but with, nevertheless, diffuse involvement of the medium-sized and more distal arteries. The corrugated appearance of the distal vessels gives an irregular, almost cork-screw aspect to many of the vessels. |

PACNS, by contrast, tends to present with a more insidious onset of dull headache, with a step-wise neurologic deterioration and course. The course of illness is prolonged, frequently over months or longer until a diagnosis is reached. Patients present due to difficulties with paresis, cognitive or personality change, visual problems, dysphasia, or ataxia. No gender predisposition is seen. Ischemic lesions are not confined to the watershed territories (Fig. 27-2). CSF findings are abnormal in the great majority of patients with pleocytosis and elevated protein count. Even with orthodox immunosuppressive therapy, angiographic findings do not reverse themselves acutely (11,12).

It seems cogent to argue that RCVS and PRES are closely related and overlapping disorders that share many

clinical and imaging features (9,10). The risk factors for both conditions are virtually identical (Table 26-1), except that the lists for PRES cast a wider net to encompass a range of complex immunologic conditions such as posttransplant immunotherapy, cancer chemotherapy, transfusion, and autoimmune disease, but it is possible that these entities are part of a shared spectrum of common pathophysiologic processes. The most discerning shibboleth between the two diagnoses appears to be the prominence of vasogenic edema within white matter with PRES. Otherwise, a description of what separates the two conditions might be captious. PRES has been associated with findings suggesting the importance of endothelial activation, reactive astrocytosis, and T-cell migration with increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) activity on biopsy (13), and at least 10% to 17% of RCVS patients are recognized as having archetypal PRES findings (4,6), although the figure is likely even higher. Within the realm of RCVS, clinical differences between groups of patients described by different authors can be ascribed to their being recruited variably from headache clinics versus inpatient stroke services, for example (3,5). It is very likely that the recognition and labeling of patients as having either PRES or RCVS is influenced by a similar bias.

clinical and imaging features (9,10). The risk factors for both conditions are virtually identical (Table 26-1), except that the lists for PRES cast a wider net to encompass a range of complex immunologic conditions such as posttransplant immunotherapy, cancer chemotherapy, transfusion, and autoimmune disease, but it is possible that these entities are part of a shared spectrum of common pathophysiologic processes. The most discerning shibboleth between the two diagnoses appears to be the prominence of vasogenic edema within white matter with PRES. Otherwise, a description of what separates the two conditions might be captious. PRES has been associated with findings suggesting the importance of endothelial activation, reactive astrocytosis, and T-cell migration with increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) activity on biopsy (13), and at least 10% to 17% of RCVS patients are recognized as having archetypal PRES findings (4,6), although the figure is likely even higher. Within the realm of RCVS, clinical differences between groups of patients described by different authors can be ascribed to their being recruited variably from headache clinics versus inpatient stroke services, for example (3,5). It is very likely that the recognition and labeling of patients as having either PRES or RCVS is influenced by a similar bias.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree