Personal narratives

Samson Tse

I am an occupational therapist and have always enjoyed working in mental health. I value the interpersonal relationships I have with people and the creative side of working in mental health. I obtained my doctoral degree from the University of Otago, New Zealand. Now I teach at the University of Auckland. My current research includes work on the recovery approach, work rehabilitation, primary health care and mental health. My personal understanding of mental health has shifted in response to years spent in clinical work, reading others’ research and conducting my own research. I have moved from concentrating on mental illness or reducing psychiatric disability to focusing on mental health with an emphasis on clients’ strengths, resilience, aspirations and goals. After meeting Carolyn Doughty in 2002, I began exploring the topic of peer-support and service-user-led interventions. How do they work? What is the evidence to support this type of service delivery? What are the critical success factors? What are the opportunities and challenges associated with delivering these types of services?

Carolyn Doughty

After working for more than a decade in community mental health, I returned to university to do a PhD in psychological medicine, working with families affected by bipolar disorder. Soon after completion I was employed by a small group of consumers who had a wider vision for growing a network of people within New Zealand that would offer peer support to tangata whai ora (those seeking wellness) and their whanau (family and significant others). Five years later, this national organisation with grassroots members from across New Zealand continues to grow and develop, linking support groups and peer organisations around the country and seeking to build the capacity of all peer workers in mental health. Since its inception, Balance New Zealand has held highly successful annual training events with a strong emphasis on recovery principles, consumer training and leadership. As an organisation it aims to ensure that any support, information and training provided will be particularly relevant, timely and responsive to consumer needs.

Introduction

Over the last three decades, there have been major shifts in the theoretical paradigm within mental health. The first shift concerned the increasing level of interest in mental health at a population or community level in response to the emerging evidence of very high lifetime prevalence of mental illness in the population particularly in Western countries. The recent Te Rau Hinengaro New Zealand Mental Health Survey (Oakley et al., 2006) estimates that the lifetime risk (up to 75 years of age) of experiencing any common mental disorder such as depression, anxiety or an alcohol or drug disorder is 46.4%. It signals that mental health problems are a concern for the whole population.

The second shift has been the move away from focusing on mental illness to considering mental health, emphasising clients’ strengths, resilience, spirituality and aspirations. People with mental health problems recover from mental illness, and they now have the potential to improve the quality of service delivery through active involvement in the mental health system. This may be in a variety of roles such as a consumer consultant or advisor, peer specialist or leading a mental health programme.

Like other health professionals, occupational therapists working in mental health have the opportunity to interact with consumers as colleagues in several ways. This may include work as a paid staff member employed by a consumer-run programme adjunct to a mental health service or working alongside a consumer consultant (Honey, 1999; Corr et al., 2005). Occupational therapists assert that the basic philosophy and value of the profession resonates very strongly with client or consumer-centred practice (Sumsion, 1999; Fossey & Harvey, 2001), but now the challenge and opportunity is to form meaningful alliances with consumers and to work with, and in, consumer-run mental health services. This chapter reviews the literature about consumer-run or consumer-led mental health services and relates observations of the sector. The specific objectives were to

Terms and concepts

In this chapter consumers are defined as individuals with mental illness who have been users of mental health services and who identify themselves as such. The terms service user and consumer are used interchangeably, acknowledging that there is variation in how individuals prefer to be addressed (Mueser et al., 1996). Literature from North America favours the term consumer, while in the UK and Europe service user is in more general use and in New Zealand the Maori term tangata whai ora (person seeking wellness) or tangata motuhake (another term for people with mental illness) are popular alternatives.

It is not straightforward to define consumer participation or recognise what a consumer-run or consumer-led service is. In Australia, consumer participation in the mental health field has come to mean ‘that service providers ensure that consumers have the opportunity to influence decision-making processes in the areas of service delivery, service planning and development, training and evaluation’ (Department of Health and Community Services, 1996, p. 5). The operational definition of most consumer-run services (CRS) moves a step beyond what has been described as consumer participation.

It embraces the notion that any support offered, by the CRS, is not controlled or dominated by professionals. This does not necessarily preclude non-consumers or professionals from being involved, but their inclusion is within the control of the consumer operators (Solomon & Draine, 1996). Indeed, it is not uncommon that qualified mental health professionals may have personal experience of mental health problems.

Here, a consumer-run, consumer-led service is defined as a programme, project or service planned, administered, delivered and evaluated by a consumer group based on needs defined by the consumer group. Operation of the service requires consumer self-governance, staffing and supervision of the staff, control of programme policy and responsibility for programme implementation. While there is generally consensus among consumers that staff in traditional mental health services are on the whole well-intentioned, system structures, resource allocation and general attitudinal issues still interact to create barriers for effective service delivery (MacNeil & Abbott, 2000).

Over the last 20 years further effort has been made to empower people with mental illness to increase their activity in and control over mental health services. The notion that consumers can participate and provide useful services to other people has been based on two important foundations. First, mental illness and its associated problems are socially constructed (Hutchison & Pedlar, 1999). Chinman et al. (2001, p. 215) argued that a proportion of any individual’s ongoing symptoms or psychiatric disability stem from the ‘poor person-environment fit between the multiple and complex needs of those with serious psychiatric disorders and community-based mental health systems.’ Therefore, consumers working together in service provision are in an ideal position to close the gap between person–environment fit and address the issues faced by their peers on a day-to-day basis such as social isolation, demoralisation, poor quality of life and difficulties in accessing mental health services. Second, because of individuals’ personal experience, they are in a unique position to make contributions that will promote positive service development and, therefore, service effectiveness by improving outcomes for mental health clients.

The potential benefits of intentional peer support include, but are not limited to, sharing similar life experiences in making sense of mental illness-related experiences, regaining a sense of control that counteracts feelings of powerlessness, role modelling recovery, instillation of hope, providing more empathetic and relevant emotional support, sharing practical information and coping strategies and strengthening social supports (Felton, et al., 1995; Mowbray et al., 2005). Consumers, as mental health service providers, are sometimes seen as more sensitive, as they more readily see the person rather than the illness. Employing service users within clinical settings or using consumer organisations as providers can facilitate cultural change within mental health workplaces by stimulating open dialogue on the attitude and behaviours of professionals. It breaks down stigma and promotes a vision of inclusion and the full participation of service users in society. It demonstrates that mental health services value consumer experience if they also employ them in providing services to others (Solomon & Draine, 1996). Lastly, CRSs or consultants can work towards social justice and enduring social change on behalf of individuals with mental illness (Mowbray et al., 2005).

CRSs can be divided into three main categories (Clay, 2005). The first, drop-in centres, are places where members can meet in a relaxing manner and participate in activities of their choice. The second, peer support programmes, provide a unique opportunity for individuals in recovery to support one another. The final, education programmes, consist of small groups in which participants learn about recovery, relapse prevention or stress-coping skills. Additional ways in which consumer involvement is possible in both partnership services or consumer-run or consumer-operated services are summarised in Box 12.1.

Despite the claims made about the desirability of consumers’ involvement, it remains a challenge to define what is meant by involving consumers in mental health services and to embed this in practice. Information on the strength of evidence about the effectiveness of consumer operated services and programmes could add value to existing mental health services in countries currently struggling with this issue, such as the US, Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand.

Box 12.1 Ways in which consumers can be involved in mental health services, modified from the work by Simpson and House (2002, 2003).

| Current or former consumer | Qualified clinical staff with personal experience of mental health problems |

| Provider in traditional mental health services, e.g., peer specialist on case management team or crisis team, mental health support worker or consumer advisor along with clinical staff | |

| Provider of independent mental health services, e.g., a consumer consultant providing information and advocacy services | |

| Trainer of mental health service providers/family or carers/other consumers or students, e.g., health professional training, health professionals’ ongoing education, intentional peer support or self management/recovery training | |

| Research, audit or evaluation of mental health services | |

| Advisors in public policy and programme development |

Adapted and reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group’s British Medical Journal, 325, 1265.

Reviewing effectiveness of consumer-run services

Methodology

A systematic method of literature searching and selection was employed. Searches were limited to English language material published from 1980 to May 2004. Peer-reviewed studies were considered if they used one of the following study designs: systematic review, randomised controlled trials (including cross-over trials), pseudo-randomised controlled trials (alternate allocation or some other method), concurrent controls or cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional or descriptive studies. Evidence, obtained from case studies without outcome data, was excluded, but these may be used as examples in the discussion. Descriptive studies, where there was no control group, were included and described but not tabled. Key outcome measures for primary studies related to the effectiveness of relevant interventions included, but not limited to, improved income, level of functioning, quality of life, attitudes to use of medication, social contacts, symptoms, inpatient days, clients’ satisfaction or perception of the service, hospital admissions, nature or duration of hospitalisations, time until first hospitalisation, arrest, emergency hospital care or homelessness, use of crisis services, self-esteem, engagement in programme, employment and relationship between client and case manager.

Studies were selected for appraisal using a two-stage process. Initially, the titles and abstracts (where available) were identified from the search strategy, including references cited in retrieved papers and review articles; these were scanned and excluded as appropriate. The full text articles were retrieved for the remaining studies and these were appraised if they fulfilled the following study inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 12.1).

The strength of the evidence in the selected studies was assessed and classified using the dimensions of evidence defined by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Canberra, Australia. These are derived directly from the literature identified as informing a particular intervention. The designations of the levels of evidence are shown in Table 12.2 and the three subdomains (level, quality and statistical precision) are collectively a measure of the strength of the evidence (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2000).

Results

Studies included in the review

The search strategy identified over 175 studies. After excluding studies from the search titles, abstracts and reference lists, 85 full text articles were retrieved, of these 57 did not fulfil the inclusion criteria and were excluded. The remaining 28 articles were eligible for inclusion and were fully appraised, consisting of 26 papers reporting primary research and 2 papers reporting systematic reviews, which will be discussed next.

Table 12.1 Inclusion/exclusion criteria for identification of relevant studies.

| Characteristic | Criteria |

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Publication type | Studies published 1980 or later |

| Sample characteristics | Adults (aged 18 years or more) |

| Study population those with Axis I psychiatric disorders as classified by DSM-IV and/or ICD-10 or earlier versions of these classifications | |

| Studies that were not restricted to participants within these age ranges, but met any of the following criteria: results were reported separately on a subgroup of participants aged at least 13 years of age; the mean age for the sample was at least 13 years | |

| Sample size | Studies with sample size 5 or more people |

| Intervention/test | Consumer-run or consumer-led mental health services for people with mental disorders |

| Comparative or controlled studies of consumer participation services within mental health services where led by consumer steering group, managed, implemented or staffed primarily by consumers | |

| Comparators | Traditional health professional-run and/or directed mental health services |

| Outcome | Studies using at least one outcome measure examining the effectiveness of the intervention in achieving improvement in function or quality of life for consumers using the service, studies looking at service delivery or studies looking at indirect measures of effectiveness |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Publication type | Non-systematic reviews, letters, editorials, expert opinion articles, comments, book chapters, articles published in abstract form and studies on animal subjects |

| Non-published work | |

| Language | Non-English language articles will be excluded |

| Study design | Evidence obtained from case studies/series where there is no outcome data |

| Sample | Studies which report outcomes for a study population including 50% or more with DSM IV alcohol or drug abuse and/or dependence as the presenting diagnosis will be excluded |

| Studies which primarily concern participants with physical or neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis | |

| Intervention/test | Studies investigating consumer involvement in mental health services but where health professionals retain 50% or more of the role of governance or management of the specific service or event (not including overall governance of the wider mental health service within which an initiative might be placed) |

| Outcome | Studies which used no quantitative outcome measure or proxy measure for collecting and reporting data from study participants |

Table 12.2 Explanation of the levels of evidence and strength of evidence (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2000).

| Level of evidence | Study design |

| I | Evidence obtained from a systematic review of all relevant randomised controlled trials |

| II | Evidence obtained from at least one properly-designed randomised controlled trial |

| III-1 | Evidence obtained from well-designed pseudo-randomised controlled trials (alternate allocation or some other method) |

| III-2 | Evidence obtained from comparative studies (including systematic reviews of such studies) with concurrent controls and allocation, not randomised, cohort studies, case–control studies or interrupted time series with a control group |

| III-3 | Evidence obtained from comparative studies with historical control, two or more single arm studies, or interrupted time series without a parallel control group |

| IV | Evidence obtained from case series, either post-test or pre-test/post-test |

| Strength of evidence | Definition |

| Level | The study design used, as an indicator of the degree to which bias has been eliminated by design |

| Quality | The methods used by investigators to minimise bias within a study design |

| Statistical precision | The p-value or, alternatively, the precision of the estimate of the effect. It reflects the degree of certainty about the existence of a true effect |

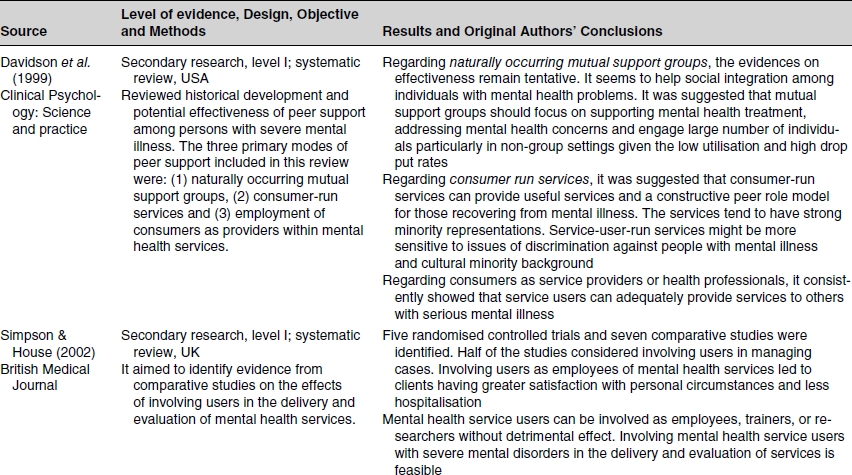

Davidson and colleagues (1999) provided a valuable commentary on the historical development and potential effectiveness of peer support among individuals with serious mental illness. Their review focused on naturally occurring mutual support groups, consumer-run services and employment of consumers as health providers. Most studies included in this review were descriptive, were limited by their small samples and low power and did not have random assignment. A more recent systematic review (Simpson and House, 2002) considered the evidence involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services. This comprehensive review was based on research published between 1966 and 2001, and included randomised controlled trials and comparative studies.

The remaining 26 eligible primary research studies included 6 randomised controlled trials (Solomon & Draine, 1996; Klein, Cnaan & Whitecraft, 1998; Clark et al., 1999; O’Donnell et al., 1999; Paulsonet al., 1999; Campbell, 2004); 7 comparative studies (Polowczyk et al., 1993; Cook et al., 1995; Felton et al., 1995; Lyonset al., 1996; Chinman et al., 2000; Chinman et al., 2001; Segal & Silverman, 2002) and 13 descriptive studies (Chen, 1990; Mowbray & Tan, 1993; Chamberlin et al., 1996; Segalet al., 1997; Torrey et al., 1998; Hutchison & Pedlar, 1999; Bentley, 2000; Petr et al., 2000; Segal et al., 2000; Meehan et al., 2002; Mowbray,et al., 2002; Salzer & Shear, 2002; Tobin et al., 2002) identified for appraisal from the search strategy.

A variety of interventions were considered. These included the involvement of current or former users of mental health services as providers in mental health services, for example, as case managers in a community mental health service (Solomon & Draine, 1996), case managers in an assertive community treatment programme (Paulson et al., 1999), client consumer advocates attached to a case management service (O’Donnell et al., 1999), peer counsellors alongside a case management service (Klein et al., 1998); peer specialists on case management teams ( Felton et al., 1995), case managers in outreach service (Chinman et al., 2000), service providers in a community outreach service (Chinman et al., 2001) and users as service providers in a mobile crisis assessment service ( Lyons et al., 1996). One study looked at current or former users of mental health services as trainers of mental health service providers (Cook et al., 1995). All these studies were published between 1993 and 2002, and these proximal publication dates indicate the relatively recent development of this field of enquiry. One unpublished randomised trial was included because of its significance for the field (Campbell, 2004).

Nineteen out of twenty-six of the evaluations to date appear to have been conducted in the US (76%). Notably, three studies from Australia (12%) have been included, two from Canada (8%) and one from the UK (4%). No published New-Zealand-based studies or evaluations were identified from the search strategy used regardless of study design.

All the Level I, II and III studies included in this review are presented in Table 12.3, using the terminology and spelling of the country of origin.

Summary of evidence

Most research in mental health draws on three major types of studies: true experiments, quasi-experiments and case–control designs. Given the limited level of knowledge in regard to self-help and consumer-operated programmes, it is appropriate to also use non-controlled study designs (Mowbray & Tan, 1993). Unlike the work by Davidson and colleagues (1999), the recent review by Simpson and House (2002) only considered controlled or comparative study designs, namely, randomised controlled trials as these are considered the gold standard for evaluating effectiveness. However, Chen (1990) asserts that evaluators should first address whether programmes are serving their targeted beneficiaries, with service delivery activities and programmes as intended, and meeting their specified objectives. Once this is assured, experimental designs for outcome evaluation may be considered, but not before. Otherwise, it cannot be known whether unsuccessful outcomes reflect failure of the specified model or failure to implement the model as specified. For this reason, selected high-quality descriptive studies were also included in this review. The following three sections discuss the literature appraised.

Table 12.3 Summary of Level I, II and III studies on the effectiveness of consumer-run or consumer-led mental health services.