Role of Anesthesia in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Psychogenic Movement Disorders

Stanley Fahn

ABSTRACT

When a patient presents with fixed postural deformities that do not yield to passive manipulation by the examiner, if those fixed postures persist in sleep, and if the physician suspects that the postural deformities may be due to a psychogenic movement disorder, then the possibility that those fixed postures are the result of contractures needs to be considered. The extent of the contractures will be the limiting factor in the degree of motor benefit that could be expected by treating the patient for a psychogenic movement disorder by the usual method of a combination of psychotherapy, physiotherapy, and medications for any psychiatric disorder. Therefore, it is important to know whether or not the fixed postures are the result of contractures, and to know the limitation of the range of motion possible because of those contractures. Examination of the fixed postures under deep anesthesia allows the physician to ascertain this knowledge, and to devise an effective plan of therapy. The essence of this chapter is that anesthesia provides information about the presence or absence of contractures, and if contractures are present, about the extent of benefit one might obtain by the routine psychotherapy-physiotherapy approach one utilizes for the treatment of psychogenic movement disorders.

An added benefit from the examination under anesthesia is the ascertainment of any fixed postures that failed to respond to passive manipulation or routine sleep not being due to contractures. This added lack of range of motion not due to contractures supports the notion that they were caused by a psychogenic movement disorder rather than an organic one. The acceptance by the patient that there was this noncontractured type of fixed posture, which can now be overcome by the patient voluntarily, adds greatly to the patient accepting the diagnosis of a psychogenic movement disorder and often leads to successful therapy of that condition. Informing the patient about the presence or absence of contractures, and about any noncontractured state of the fixed postures, aids in the patient often immediately

eliminating the noncontractured component of the fixed postures. Fahn writes:

eliminating the noncontractured component of the fixed postures. Fahn writes:

An accurate diagnosis of psychogenic movement disorder as opposed to diagnosing an organic movement disorder is often one of the most difficult tasks in the movement disorder specialty. It is extremely important to be correct in the diagnosis, because only then can the appropriate therapy be initiated. The results of an incorrect diagnosis are detrimental. If a patient has a psychogenic disorder that is misdiagnosed, the patient will be given inappropriate and potentially harmful medication and is also denied the proper treatment to overcome the disabling symptoms. By postponing the appropriate psychiatric treatment, the cycle of disability is perpetuated. Untreated patients with psychogenic movement disorders are at risk for becoming career invalids with chronic disability (1).

INTRODUCTION

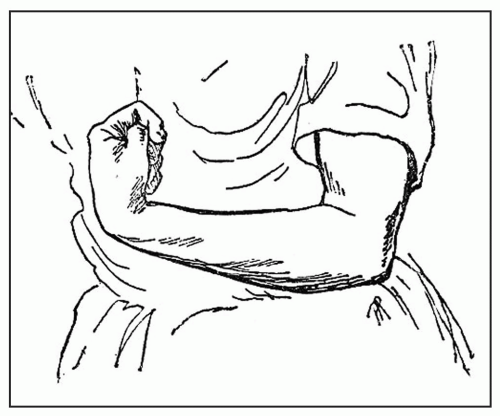

The first step in the diagnosis of a psychogenic disorder, like most medical conditions, is to be suspicious of the possibility of that diagnosis. In movement disorders, that suspicion rests on the phenomenology of the abnormal pattern of movements and on certain clues (1) in the history and examination. Fixed postures are sustained postures that resist passive movement, and such fixed postures are highly likely to be due to a psychogenic dystonia (2, 3, 4).

Once a psychogenic movement disorder is suspected, the next step is to establish the correct diagnosis, that is, document that the abnormal movements are indeed due to a psychogenic etiology. Just being suspicious that the signs and symptoms are psychogenic is insufficient for the diagnosis of documented psychogenic disorder. Fahn and Williams (2) categorized patients into four levels of certainty as to the likelihood of their having a psychogenic movement disorder. These four degrees of certainty are (i) documented psychogenic disorder, (ii) clinically established psychogenic disorder, (iii) probable psychogenic disorder, and (iv) possible psychogenic movement disorder. This classification has been used by subsequent authors (5, 6, 7). In order for the disorder to be documented as being psychogenic, the symptoms must be relieved by psychotherapy, by the clinician utilizing psychological suggestion including physiotherapy, by administration of placebos (again with suggestion being a part of this approach), or by the patient being witnessed as being free of symptoms when left alone, supposedly unobserved (1). Two special problems exist: (i) when the abnormal movements are paroxysmal, because getting better at times is part of a paroxysmal syndrome, so one cannot be certain if the improvement was due to the psychotherapeutic treatment for psychogenicity; and (ii) if the abnormal movements had led to a fixed posture that resists passive movement possibly due to the development of contractures.

A contracture in a muscle is a shortened muscle that is resistant to passive stretch and is usually due to fibrosis of the muscle, ligaments, tendons, or the joints, preventing the muscle from stretching to its normal length. (An ankylosed joint due to bony growth would also result in a fixed posture and would be in the differential diagnoses of fixed postures along with contracture. X-rays would be able to detect such ankylotic joints, and we will not consider ankylosis any further.) The contracture thus presents as a fixed posture, that is, a posture that cannot be relieved by the examiner trying to straighten out the abnormally positioned body part. However, a fixed posture due to psychogenicity may be due to a contracture or may resemble a contracture, merely by resisting passive movement. How to distinguish between a contracture and a noncontracture fixed posture is the essence of this chapter. The ultimate, documented diagnosis of a psychogenic dystonia, as stated above, depends on getting the patient better; getting better, in terms of relieving fixed postures, depends on knowing if contractures are present and if noncontractured fixed postures are present.

The shortened muscle, if due entirely to a contracture, is electrically silent. Metabolic diseases, such as McArdle disease (8) due to muscle phosphorylase deficiency, can cause electrically silent contractions, thus technically physiologic contractures (9). But these disorders do not lead to persistent contractures. This type of physiologic contracture appears with protracted exercise, and is most readily seen in phosphorylase deficiency with anaerobic exercise, where the muscle’s energy is derived from glycolysis and not

mitochondria. Further discussion of physiologic contractures is not part of this chapter.

mitochondria. Further discussion of physiologic contractures is not part of this chapter.

Figure 29.2 Drawing by Richer. “Hysterical flexion contracture of the right leg.” (From Oppenheim H. In: Bruce A, ed. Text-book of nervous diseases. Edinburgh: Otto Schulze and Co., 1911:1079, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|