Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

7.1 Schizophrenia

7.1 Schizophrenia

Although schizophrenia is discussed as if it is a single disease, it probably comprises a group of disorders with heterogeneous etiologies, and it includes patients whose clinical presentations, treatment response, and courses of illness vary. Signs and symptoms are variable and include changes in perception, emotion, cognition, thinking, and behavior. The expression of these manifestations varies across patients and over time, but the effect of the illness is always severe and is usually long lasting. The disorder usually begins before age 25 years, persists throughout life, and affects persons of all social classes. Both patients and their families often suffer from poor care and social ostracism because of widespread ignorance about the disorder. Schizophrenia is one of the most common of the serious mental disorders, but its essential nature remains to be clarified; thus, it is sometimes referred to as a syndrome, as the group of schizophrenias, or as in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the schizophrenia spectrum. Clinicians should appreciate that the diagnosis of schizophrenia is based entirely on the psychiatric history and mental status examination. There is no laboratory test for schizophrenia.

HISTORY

Written descriptions of symptoms commonly observed today in patients with schizophrenia are found throughout history. Early Greek physicians described delusions of grandeur, paranoia, and deterioration in cognitive functions and personality. It was not until the 19th century, however, that schizophrenia emerged as a medical condition worthy of study and treatment. Two major figures in psychiatry and neurology who studied the disorder were Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) and Eugene Bleuler (1857–1939). Earlier, Benedict Morel (1809–1873), a French psychiatrist, had used the term démence précoce to describe deteriorated patients whose illnesses began in adolescence.

Emil Kraepelin

Kraepelin (Fig. 7.1-1) translated Morel’s démence précoce into dementia precox, a term that emphasized the change in cognition (dementia) and early onset (precox) of the disorder. Patients with dementia precox were described as having a long-term deteriorating course and the clinical symptoms of hallucinations and delusions. Kraepelin distinguished these patients from those who underwent distinct episodes of illness alternating with periods of normal functioning, which he classified as having manic-depressive psychosis. Another separate condition called paranoia was characterized by persistent persecutory delusions. These patients lacked the deteriorating course of dementia precox and the intermittent symptoms of manic-depressive psychosis.

FIGURE 7.1-1

Emil Kraepelin, 1856–1926. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD.)

Eugene Bleuler

Bleuler (Fig. 7.1-2) coined the term schizophrenia, which replaced dementia precox in the literature. He chose the term to express the presence of schisms among thought, emotion, and behavior in patients with the disorder. Bleuler stressed that, unlike Kraepelin’s concept of dementia precox, schizophrenia need not have a deteriorating course. This term is often misconstrued, especially by lay people, to mean split personality. Split personality, called dissociative identity disorder, differs completely from schizophrenia (see Chapter 12).

FIGURE 7.1-2

Eugene Bleuler, 1857–1939. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD.)

The Four As. Bleuler identified specific fundamental (or primary) symptoms of schizophrenia to develop his theory about the internal mental schisms of patients. These symptoms included associational disturbances of thought, especially looseness, affective disturbances, autism, and ambivalence, summarized as the four As: associations, affect, autism, and ambivalence. Bleuler also identified accessory (secondary) symptoms, which included the symptoms that Kraepelin saw as major indicators of dementia precox: hallucinations and delusions.

Other Theorists

Ernst Kretschmer (1888–1926). Kretschmer compiled data to support the idea that schizophrenia occurred more often among persons with asthenic (i.e., slender, lightly muscled physiques), athletic, or dysplastic body types rather than among persons with pyknic (i.e., short, stocky physiques) body types. He thought the latter were more likely to incur bipolar disorders. His observations may seem strange, but they are not inconsistent with a superficial impression of the body types in many persons with schizophrenia.

Kurt Schneider (1887–1967). Schneider contributed a description of first-rank symptoms, which, he stressed, were not specific for schizophrenia and were not to be rigidly applied but were useful for making diagnoses. He emphasized that in patients who showed no first-rank symptoms, the disorder could be diagnosed exclusively on the basis of second-rank symptoms and an otherwise typical clinical appearance. Clinicians frequently ignore his warnings and sometimes see the absence of first-rank symptoms during a single interview as evidence that a person does not have schizophrenia.

Karl Jaspers (1883–1969). Jaspers, a psychiatrist and philosopher, played a major role in developing existential psychoanalysis. He was interested in the phenomenology of mental illness and the subjective feelings of patients with mental illness. His work paved the way toward trying to understand the psychological meaning of schizophrenic signs and symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations.

Adolf Meyer (1866–1950). Meyer, the founder of psychobiology, saw schizophrenia as a reaction to life stresses. It was a maladaptation that was understandable in terms of the patient’s life experiences. Meyer’s view was represented in the nomenclature of the 1950s, which referred to the schizophrenic reaction. In later editions of DSM, the term reaction was dropped.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is about 1 percent, which means that about one person in 100 will develop schizophrenia during their lifetime. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health reported a lifetime prevalence of 0.6 to 1.9 percent. In the United States, about 0.05 percent of the total population is treated for schizophrenia in any single year, and only about half of all patients with schizophrenia obtain treatment, despite the severity of the disorder.

Gender and Age

Schizophrenia is equally prevalent in men and women. The two genders differ, however, in the onset and course of illness. Onset is earlier in men than in women. More than half of all male schizophrenia patients, but only one-third of all female schizophrenia patients, are first admitted to a psychiatric hospital before age 25 years. The peak ages of onset are 10 to 25 years for men and 25 to 35 years for women. Unlike men, women display a bimodal age distribution, with a second peak occurring in middle age. Approximately 3 to 10 percent of women with schizophrenia present with disease onset after age 40 years. About 90 percent of patients in treatment for schizophrenia are between 15 and 55 years old. Onset of schizophrenia before age 10 years or after age 60 years is extremely rare. Some studies have indicated that men are more likely to be impaired by negative symptoms (described later) than are women and that women are more likely to have better social functioning than are men before disease onset. In general, the outcome for female schizophrenia patients is better than that for male schizophrenia patients. When onset occurs after age 45 years, the disorder is characterized as late-onset schizophrenia.

Reproductive Factors

The use of psychopharmacological drugs, the open-door policies in hospitals, the deinstitutionalization in state hospitals, and the emphasis on rehabilitation and community-based care for patients have all led to an increase in the marriage and fertility rates among persons with schizophrenia. Because of these factors, the number of children born to parents with schizophrenia is continually increasing. The fertility rate for persons with schizophrenia is close to that for the general population. First-degree biological relatives of persons with schizophrenia have a ten times greater risk for developing the disease than the general population.

Medical Illness

Persons with schizophrenia have a higher mortality rate from accidents and natural causes than the general population. Institution- or treatment-related variables do not explain the increased mortality rate, but the higher rate may be related to the fact that the diagnosis and treatment of medical and surgical conditions in schizophrenia patients can be clinical challenges. Several studies have shown that up to 80 percent of all schizophrenia patients have significant concurrent medical illnesses and that up to 50 percent of these conditions may be undiagnosed.

Infection and Birth Season

Persons who develop schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in the winter and early spring and less likely to have been born in late spring and summer. In the Northern Hemisphere, including the United States, persons with schizophrenia are more often born in the months from January to April. In the Southern Hemisphere, persons with schizophrenia are more often born in the months from July to September. Season-specific risk factors, such as a virus or a seasonal change in diet, may be operative. Another hypothesis is that persons with a genetic predisposition for schizophrenia have a decreased biological advantage to survive season-specific insults.

Studies have pointed to gestational and birth complications, exposure to influenza epidemics, maternal starvation during pregnancy, Rhesus factor incompatibility, and an excess of winter births in the etiology of schizophrenia. The nature of these factors suggests a neurodevelopmental pathological process in schizophrenia, but the exact pathophysiological mechanism associated with these risk factors is not known.

Epidemiological data show a high incidence of schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to influenza during several epidemics of the disease. Some studies show that the frequency of schizophrenia is increased after exposure to influenza—which occurs in the winter—during the second trimester of pregnancy. Other data supporting a viral hypothesis are an increased number of physical anomalies at birth, an increased rate of pregnancy and birth complications, seasonality of birth consistent with viral infection, geographical clusters of adult cases, and seasonality of hospitalizations.

Viral theories stem from the fact that several specific viral theories have the power to explain the particular localization of pathology necessary to account for a range of manifestations in schizophrenia without overt febrile encephalitis.

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse is common in schizophrenia. The lifetime prevalence of any drug abuse (other than tobacco) is often greater than 50 percent. For all drugs of abuse (other than tobacco), abuse is associated with poorer function. In one population-based study, the lifetime prevalence of alcohol within schizophrenia was 40 percent. Alcohol abuse increases risk of hospitalization and, in some patients, may increase psychotic symptoms. People with schizophrenia have an increased prevalence of abuse of common street drugs. There has been particular interest in the association between cannabis and schizophrenia. Those reporting high levels of cannabis use (more than 50 occasions) were at sixfold increased risk of schizophrenia compared with nonusers. The use of amphetamines, cocaine, and similar drugs should raise particular concern because of their marked ability to increase psychotic symptoms.

Nicotine. Up to 90 percent of schizophrenia patients may be dependent on nicotine. Apart from smoking-associated mortality, nicotine decreases the blood concentrations of some antipsychotics. There are suggestions that the increased prevalence in smoking is due, at least in part, to brain abnormalities in nicotinic receptors. A specific polymorphism in a nicotinic receptor has been linked to a genetic risk for schizophrenia. Nicotine administration appears to improve some cognitive impairments and parkinsonism in schizophrenia, possibly because of nicotine-dependent activation of dopamine neurons. Recent studies have also demonstrated that nicotine may decrease positive symptoms such as hallucinations in schizophrenia patients by its effect on nicotine receptors in the brain that reduce the perception of outside stimuli, especially noise. In that sense, smoking is a form of self-medication.

Population Density

The prevalence of schizophrenia has been correlated with local population density in cities with populations of more than 1 million people. The correlation is weaker in cities of 100,000 to 500,000 people and is absent in cities with fewer than 10,000 people. The effect of population density is consistent with the observation that the incidence of schizophrenia in children of either one or two parents with schizophrenia is twice as high in cities as in rural communities. These observations suggest that social stressors in urban settings may affect the development of schizophrenia in persons at risk.

Socioeconomic and Cultural Factors

Economics. Because schizophrenia begins early in life; causes significant and long-lasting impairments; makes heavy demands for hospital care; and requires ongoing clinical care, rehabilitation, and support services, the financial cost of the illness in the United States is estimated to exceed that of all cancers combined. Patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia are reported to account for 15 to 45 percent of homeless Americans.

Hospitalization. The development of effective antipsychotic drugs and changes in political and popular attitudes toward the treatment and the rights of persons who are mentally ill have dramatically changed the patterns of hospitalization for schizophrenia patients since the mid-1950s. Even with antipsychotic medication, however, the probability of readmission within 2 years after discharge from the first hospitalization is about 40 to 60 percent. Patients with schizophrenia occupy about 50 percent of all mental hospital beds and account for about 16 percent of all psychiatric patients who receive any treatment.

ETIOLOGY

Genetic Factors

There is a genetic contribution to some, perhaps all, forms of schizophrenia, and a high proportion of the variance in liability to schizophrenia is due to additive genetic effects. For example, schizophrenia and schizophrenia-related disorders (e.g., schizotypal personality disorder) occur at an increased rate among the biological relatives of patients with schizophrenia. The likelihood of a person having schizophrenia is correlated with the closeness of the relationship to an affected relative (e.g., first- or second-degree relative). In the case of monozygotic twins who have identical genetic endowment, there is an approximately 50 percent concordance rate for schizophrenia. This rate is four to five times the concordance rate in dizygotic twins or the rate of occurrence found in other first-degree relatives (i.e., siblings, parents, or offspring). The role of genetic factors is further reflected in the drop-off in the occurrence of schizophrenia among second- and third-degree relatives, in whom one would hypothesize a decreased genetic loading. The finding of a higher rate of schizophrenia among the biological relatives of an adopted-away person who develops schizophrenia, compared with the adoptive, nonbiological relatives who rear the patient, provides further support to the genetic contribution in the etiology of schizophrenia. Nevertheless, the monozygotic twin data clearly demonstrate the fact that individuals who are genetically vulnerable to schizophrenia do not inevitably develop schizophrenia; other factors (e.g., environment) must be involved in determining a schizophrenia outcome. If a vulnerability-liability model of schizophrenia is correct in its postulation of an environmental influence, then other biological or psychosocial environment factors may prevent or cause schizophrenia in the genetically vulnerable individual.

Some data indicate that the age of the father has a correlation with the development of schizophrenia. In studies of schizophrenia patients with no history of illness in either the maternal or paternal line, it was found that those born from fathers older than the age of 60 years were vulnerable to developing the disorder. Presumably, spermatogenesis in older men is subject to greater epigenetic damage than in younger men.

The modes of genetic transmission in schizophrenia are unknown, but several genes appear to make a contribution to schizophrenia vulnerability. Linkage and association genetic studies have provided strong evidence for nine linkage sites: 1q, 5q, 6p, 6q, 8p, 10p, 13q, 15q, and 22q. Further analyses of these chromosomal sites have led to the identification of specific candidate genes, and the best current candidates are α-7 nicotinic receptor, DISC 1, GRM 3, COMT, NRG 1, RGS 4, and G 72. Recently, mutations of the genes dystrobrevin (DTNBP1) and neureglin 1 have been found to be associated with negative features of schizophrenia.

Biochemical Factors

Dopamine Hypothesis. The simplest formulation of the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia posits that schizophrenia results from too much dopaminergic activity. The theory evolved from two observations. First, the efficacy and the potency of many antipsychotic drugs (i.e., the dopamine receptor antagonists [DRAs]) are correlated with their ability to act as antagonists of the dopamine type 2 (D2) receptor. Second, drugs that increase dopaminergic activity, notably cocaine and amphetamine, are psychotomimetic. The basic theory does not elaborate on whether the dopaminergic hyperactivity is due to too much release of dopamine, too many dopamine receptors, hypersensitivity of the dopamine receptors to dopamine, or a combination of these mechanisms. Which dopamine tracts in the brain are involved is also not specified in the theory, although the mesocortical and mesolimbic tracts are most often implicated. The dopaminergic neurons in these tracts project from their cell bodies in the midbrain to dopaminoceptive neurons in the limbic system and the cerebral cortex.

Excessive dopamine release in patients with schizophrenia has been linked to the severity of positive psychotic symptoms. Position emission tomography studies of dopamine receptors document an increase in D2 receptors in the caudate nucleus of drug-free patients with schizophrenia. There have also been reports of increased dopamine concentration in the amygdala, decreased density of the dopamine transporter, and increased numbers of dopamine type 4 receptors in the entorhinal cortex.

Serotonin. Current hypotheses posit serotonin excess as a cause of both positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. The robust serotonin antagonist activity of clozapine and other second-generation antipsychotics coupled with the effectiveness of clozapine to decrease positive symptoms in chronic patients has contributed to the validity of this proposition.

Norepinephrine. Anhedonia—the impaired capacity for emotional gratification and the decreased ability to experience pleasure—has long been noted to be a prominent feature of schizophrenia. A selective neuronal degeneration within the norepinephrine reward neural system could account for this aspect of schizophrenic symptomatology. However, biochemical and pharmacological data bearing on this proposal are inconclusive.

GABA. The inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia based on the finding that some patients with schizophrenia have a loss of GABAergic neurons in the hippocampus. GABA has a regulatory effect on dopamine activity, and the loss of inhibitory GABAergic neurons could lead to the hyperactivity of dopaminergic neurons.

Neuropeptides. Neuropeptides, such as substance P and neurotensin, are localized with the catecholamine and indolamine neurotransmitters and influence the action of these neurotransmitters. Alteration in neuropeptide mechanisms could facilitate, inhibit, or otherwise alter the pattern of firing these neuronal systems.

Glutamate. Glutamate has been implicated because ingestion of phencyclidine, a glutamate antagonist, produces an acute syndrome similar to schizophrenia. The hypotheses proposed about glutamate include those of hyperactivity, hypoactivity, and glutamate-induced neurotoxicity.

Acetylcholine and Nicotine. Postmortem studies in schizophrenia have demonstrated decreased muscarinic and nicotinic receptors in the caudate-putamen, hippocampus, and selected regions of the prefrontal cortex. These receptors play a role in the regulation of neurotransmitter systems involved in cognition, which is impaired in schizophrenia.

Neuropathology

In the 19th century, neuropathologists failed to find a neuropathological basis for schizophrenia, and thus they classified schizophrenia as a functional disorder. By the end of the 20th century, however, researchers had made significant strides in revealing a potential neuropathological basis for schizophrenia, primarily in the limbic system and the basal ganglia, including neuropathological or neurochemical abnormalities in the cerebral cortex, the thalamus, and the brainstem. The loss of brain volume widely reported in schizophrenic brains appears to result from reduced density of the axons, dendrites, and synapses that mediate associative functions of the brain. Synaptic density is highest at age 1 year and then is pared down to adult values in early adolescence. One theory, based in part on the observation that patients often develop schizophrenic symptoms during adolescence, holds that schizophrenia results from excessive pruning of synapses during this phase of development.

Cerebral Ventricles. Computed tomography (CT) scans of patients with schizophrenia have consistently shown lateral and third ventricular enlargement and some reduction in cortical volume. Reduced volumes of cortical gray matter have been demonstrated during the earliest stages of the disease. Several investigators have attempted to determine whether the abnormalities detected by CT are progressive or static. Some studies have concluded that the lesions observed on CT scan are present at the onset of the illness and do not progress. Other studies, however, have concluded that the pathological process visualized on CT scan continues to progress during the illness. Thus, whether an active pathological process is continuing to evolve in schizophrenia patients is still uncertain.

Reduced Symmetry. There is a reduced symmetry in several brain areas in schizophrenia, including the temporal, frontal, and occipital lobes. This reduced symmetry is believed by some investigators to originate during fetal life and to be indicative of a disruption in brain lateralization during neurodevelopment.

Limbic System. Because of its role in controlling emotions, the limbic system has been hypothesized to be involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Studies of postmortem brain samples from schizophrenia patients have shown a decrease in the size of the region, including the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the parahippocampal gyrus. This neuropathological finding agrees with the observation made by magnetic resonance imaging studies of patients with schizophrenia. The hippocampus is not only smaller in size in schizophrenia but is also functionally abnormal as indicated by disturbances in glutamate transmission. Disorganization of the neurons within the hippocampus has also been seen in brain tissue sections of schizophrenia patients compared with healthy control participants without schizophrenia.

Prefrontal Cortex. There is considerable evidence from postmortem brain studies that supports anatomical abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Functional deficits in the prefrontal brain imaging region have also been demonstrated. It has long been noted that several symptoms of schizophrenia mimic those found in persons with prefrontal lobotomies or frontal lobe syndromes.

Thalamus. Some studies of the thalamus show evidence of volume shrinkage or neuronal loss, in particular subnuclei. The medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus, which has reciprocal connections with the prefrontal cortex, has been reported to contain a reduced number of neurons. The total number of neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes is reduced by 30 to 45 percent in schizophrenia patients. This putative finding does not appear to be due to the effects of antipsychotic drugs because the volume of the thalamus is similar in size between patients with schizophrenia treated chronically with medication and neuroleptic-naive subjects.

Basal Ganglia and Cerebellum. The basal ganglia and cerebellum have been of theoretical interest in schizophrenia for at least two reasons. First, many patients with schizophrenia show odd movements, even in the absence of medication-induced movement disorders (e.g., tardive dyskinesia). The odd movements can include an awkward gait, facial grimacing, and stereotypies. Because the basal ganglia and cerebellum are involved in the control of movement, disease in these areas is implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Second, the movement disorders involving the basal ganglia (e.g., Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease) are the ones most commonly associated with psychosis. Neuropathological studies of the basal ganglia have produced variable and inconclusive reports about cell loss or the reduction of volume of the globus pallidus and the substantia nigra. Studies have also shown an increase in the number of D2 receptors in the caudate, the putamen, and the nucleus accumbens. The question remains, however, whether the increase is secondary to the patient having received antipsychotic medications. Some investigators have begun to study the serotonergic system in the basal ganglia; a role for serotonin in psychotic disorder is suggested by the clinical usefulness of antipsychotic drugs that are serotonin antagonists (e.g., clozapine, risperidone).

Neural Circuits

There has been a gradual evolution from conceptualizing schizophrenia as a disorder that involves discrete areas of the brain to a perspective that views schizophrenia as a disorder of brain neural circuits. For example, as mentioned previously, the basal ganglia and cerebellum are reciprocally connected to the frontal lobes, and the abnormalities in frontal lobe function seen in some brain imaging studies may be due to disease in either area rather than in the frontal lobes themselves. It is also hypothesized that an early developmental lesion of the dopaminergic tracts to the prefrontal cortex results in the disturbance of prefrontal and limbic system function and leads to the positive and negative symptoms and cognitive impairments observed in patients with schizophrenia.

Of particular interest in the context of neural circuit hypotheses linking the prefrontal cortex and limbic system are studies demonstrating a relationship between hippocampal morphological abnormalities and disturbances in prefrontal cortex metabolism or function (or both). Data from functional and structural imaging studies in humans suggest that whereas dysfunction of the anterior cingulate basal ganglia thalamocortical circuit underlies the production of positive psychotic symptoms, dysfunction of the dorsolateral prefrontal circuit underlies the production of primary, enduring, negative or deficit symptoms. There is a neural basis for cognitive functions that is impaired in patients with schizophrenia. The observation of the relationship among impaired working memory performance, disrupted prefrontal neuronal integrity, altered prefrontal, cingulate, and inferior parietal cortex, and altered hippocampal blood flow provides strong support for disruption of the normal working memory neural circuit in patients with schizophrenia. The involvement of this circuit, at least for auditory hallucinations, has been documented in a number of functional imaging studies that contrast hallucinating and nonhallucinating patients.

Brain Metabolism

Studies using magnetic resonance spectroscopy, a technique that measures the concentration of specific molecules in the brain, found that patients with schizophrenia had lower levels of phosphomonoester and inorganic phosphate and higher levels of phosphodiester than a control group. Furthermore, concentrations of N-acetyl aspartate, a marker of neurons, were lower in the hippocampus and frontal lobes of patients with schizophrenia.

Applied Electrophysiology

Electroencephalographic studies indicate that many schizophrenia patients have abnormal records, increased sensitivity to activation procedures (e.g., frequent spike activity after sleep deprivation), decreased alpha activity, increased theta and delta activity, possibly more epileptiform activity than usual, and possibly more left-sided abnormalities than usual. Schizophrenia patients also exhibit an inability to filter out irrelevant sounds and are extremely sensitive to background noise. The flooding of sound that results makes concentration difficult and may be a factor in the production of auditory hallucinations. This sound sensitivity may be associated with a genetic defect.

Complex Partial Epilepsy. Schizophrenia-like psychoses have been reported to occur more frequently than expected in patients with complex partial seizures, especially seizures involving the temporal lobes. Factors associated with the development of psychosis in these patients include a left-sided seizure focus, medial temporal location of the lesion, and an early onset of seizures. The first-rank symptoms described by Schneider may be similar to symptoms of patients with complex partial epilepsy and may reflect the presence of a temporal lobe disorder when seen in patients with schizophrenia.

Evoked Potentials. A large number of abnormalities in evoked potential among patients with schizophrenia has been described. The P300 has been most studied and is defined as a large, positive evoked-potential wave that occurs about 300 milliseconds after a sensory stimulus is detected. The major source of the P300 wave may be located in the limbic system structures of the medial temporal lobes. In patients with schizophrenia, the P300 has been reported to be statistically smaller than in comparison groups. Abnormalities in the P300 wave have also been reported to be more common in children who, because they have affected parents, are at high risk for schizophrenia. Whether the characteristics of the P300 represent a state or a trait phenomenon remains controversial. Other evoked potentials reported to be abnormal in patients with schizophrenia are the N100 and the contingent negative variation. The N100 is a negative wave that occurs about 100 milliseconds after a stimulus, and the contingent negative variation is a slowly developing, negative-voltage shift following the presentation of a sensory stimulus that is a warning for an upcoming stimulus. The evoked-potential data have been interpreted as indicating that although patients with schizophrenia are unusually sensitive to a sensory stimulus (larger early evoked potentials), they compensate for the increased sensitivity by blunting the processing of information at higher cortical levels (indicated by smaller late evoked potentials).

Eye Movement Dysfunction

The inability to follow a moving visual target accurately is the defining basis for the disorders of smooth visual pursuit and disinhibition of saccadic eye movements seen in patients with schizophrenia. Eye movement dysfunction may be a trait marker for schizophrenia; it is independent of drug treatment and clinical state and is also seen in first-degree relatives of probands with schizophrenia. Various studies have reported abnormal eye movements in 50 to 85 percent of patients with schizophrenia compared with about 25 percent in psychiatric patients without schizophrenia and fewer than 10 percent in nonpsychiatrically ill control participant.

Psychoneuroimmunology

Several immunological abnormalities have been associated with patients who have schizophrenia. The abnormalities include decreased T-cell interleukin-2 production, reduced number and responsiveness of peripheral lymphocytes, abnormal cellular and humoral reactivity to neurons, and the presence of brain-directed (antibrain) antibodies. The data can be interpreted variously as representing the effects of a neurotoxic virus or of an endogenous autoimmune disorder. Most carefully conducted investigations that have searched for evidence of neurotoxic viral infections in schizophrenia have had negative results, although epidemiological data show a high incidence of schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to influenza during several epidemics of the disease. Other data supporting a viral hypothesis are an increased number of physical anomalies at birth, an increased rate of pregnancy and birth complications, seasonality of birth consistent with viral infection, geographical clusters of adult cases, and seasonality of hospitalizations. Nonetheless, the inability to detect genetic evidence of viral infection reduces the significance of all circumstantial data. The possibility of autoimmune brain antibodies has some data to support it; the pathophysiological process, if it exists, however, probably explains only a subset of the population with schizophrenia.

Psychoneuroendocrinology

Many reports describe neuroendocrine differences between groups of patients with schizophrenia and groups of control subjects. For example, results of the dexamethasone-suppression test have been reported to be abnormal in various subgroups of patients with schizophrenia, although the practical or predictive value of the test in schizophrenia has been questioned. One carefully done report, however, has correlated persistent nonsuppression on the dexamethasone-suppression test in schizophrenia with a poor long-term outcome.

Some data suggest decreased concentrations of luteinizing hormone or follicle-stimulating hormone, perhaps correlated with age of onset and length of illness. Two additional reported abnormalities may be correlated with the presence of negative symptoms: a blunted release of prolactin and growth hormone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone or thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulation and a blunted release of growth hormone on apomorphine stimulation.

PSYCHOSOCIAL AND PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORIES

If schizophrenia is a disease of the brain, it is likely to parallel diseases of other organs (e.g., myocardial infarctions, diabetes) whose courses are affected by psychosocial stress. Thus, clinicians should consider both psychosocial and biological factors affecting schizophrenia.

The disorder affects individual patients, each of whom has a unique psychological makeup. Although many psychodynamic theories about the pathogenesis of schizophrenia seem outdated, perceptive clinical observations can help contemporary clinicians understand how the disease may affect a patient’s psyche.

Psychoanalytic Theories. Sigmund Freud postulated that schizophrenia resulted from developmental fixations early in life. These fixations produce defects in ego development, and he postulated that such defects contributed to the symptoms of schizophrenia. Ego disintegration in schizophrenia represents a return to the time when the ego was not yet developed or had just begun to be established. Because the ego affects the interpretation of reality and the control of inner drives, such as sex and aggression, these ego functions are impaired. Thus, intrapsychic conflict arising from the early fixations and the ego defect, which may have resulted from poor early object relations, fuel the psychotic symptoms.

As described by Margaret Mahler, there are distortions in the reciprocal relationship between the infant and the mother. The child is unable to separate from, and progress beyond, the closeness and complete dependence that characterize the mother–child relationship in the oral phase of development. As a result, the person’s identity never becomes secure.

Paul Federn hypothesized that the defect in ego functions permits intense hostility and aggression to distort the mother–infant relationship, which leads to eventual personality disorganization and vulnerability to stress. The onset of symptoms during adolescence occurs when teenagers need a strong ego to function independently, to separate from the parents, to identify tasks, to control increased internal drives, and to cope with intense external stimulation.

Harry Stack Sullivan viewed schizophrenia as a disturbance in interpersonal relatedness. The patient’s massive anxiety creates a sense of unrelatedness that is transformed into parataxic distortions, which are usually, but not always, persecutory. To Sullivan, schizophrenia is an adaptive method used to avoid panic, terror, and disintegration of the sense of self. The source of pathological anxiety results from cumulative experiential traumas during development.

Psychoanalytic theory also postulates that the various symptoms of schizophrenia have symbolic meaning for individual patients. For example, fantasies of the world coming to an end may indicate a perception that a person’s internal world has broken down. Feelings of inferiority are replaced by delusions of grandeur and omnipotence. Hallucinations may be substitutes for a patient’s inability to deal with objective reality and may represent inner wishes or fears. Delusions, similar to hallucinations, are regressive, restitutive attempts to create a new reality or to express hidden fears or impulses (Fig. 7.1-3).

Regardless of the theoretical model, all psychodynamic approaches are founded on the premise that psychotic symptoms have meaning in schizophrenia. Patients, for example, may become grandiose after an injury to their self-esteem. Similarly, all theories recognize that human relatedness may be terrifying for persons with schizophrenia. Although research on the efficacy of psychotherapy with schizophrenia shows mixed results, concerned persons who offer compassion and a sanctuary in the confusing world of schizophrenia must be a cornerstone of any overall treatment plan. Long-term follow-up studies show that some patients who bury psychotic episodes probably do not benefit from exploratory psychotherapy, but those who are able to integrate the psychotic experience into their lives may benefit from some insight-oriented approaches. There is renewed interest in the use of long-term individual psychotherapy in the treatment of schizophrenia, especially when combined with medication.

FIGURE 7.1-3

This patient wore suits too large for him in the delusional belief that he would appear taller to others. (Courtesy of Emil Kraepelin, M.D.)

Learning Theories. According to learning theorists, children who later have schizophrenia learn irrational reactions and ways of thinking by imitating parents who have their own significant emotional problems. In learning theory, the poor interpersonal relationships of persons with schizophrenia develop because of poor models for learning during childhood.

Family Dynamics

In a study of British 4-year-old children, those who had a poor mother–child relationship had a sixfold increase in the risk of developing schizophrenia, and offspring from schizophrenic mothers who were adopted away at birth were more likely to develop the illness if they were reared in adverse circumstances compared with those raised in loving homes by stable adoptive parents. Nevertheless, no well-controlled evidence indicates that a specific family pattern plays a causative role in the development of schizophrenia. Some patients with schizophrenia do come from dysfunctional families, just as do many nonpsychiatrically ill persons. It is important, however, not to overlook pathological family behavior that can significantly increase the emotional stress with which a vulnerable patient with schizophrenia must cope.

Double Bind. The double-bind concept was formulated by Gregory Bateson and Donald Jackson to describe a hypothetical family in which children receive conflicting parental messages about their behavior, attitudes, and feelings. In Bateson’s hypothesis, children withdraw into a psychotic state to escape the unsolvable confusion of the double bind. Unfortunately, the family studies that were conducted to validate the theory were seriously flawed methodologically. The theory has value only as a descriptive pattern, not as a causal explanation of schizophrenia. An example of a double bind is a parent who tells a child to provide cookies for his or her friends and then chastises the child for giving away too many cookies to playmates.

Schisms and Skewed Families. Theodore Lidz described two abnormal patterns of family behavior. In one family type, with a prominent schism between the parents, one parent is overly close to a child of the opposite gender. In the other family type, a skewed relationship between a child and one parent involves a power struggle between the parents and the resulting dominance of one parent. These dynamics stress the tenuous adaptive capacity of the person with schizophrenia.

Pseudomutual and Pseudohostile Families. As described by Lyman Wynne, some families suppress emotional expression by consistently using pseudomutual or pseudohostile verbal communication. In such families, a unique verbal communication develops, and when a child leaves home and must relate to other persons, problems may arise. The child’s verbal communication may be incomprehensible to outsiders.

Expressed Emotion. Parents or other caregivers may behave with overt criticism, hostility, and overinvolvement toward a person with schizophrenia. Many studies have indicated that in families with high levels of expressed emotion, the relapse rate for schizophrenia is high. The assessment of expressed emotion involves analyzing both what is said and the manner in which it is said.

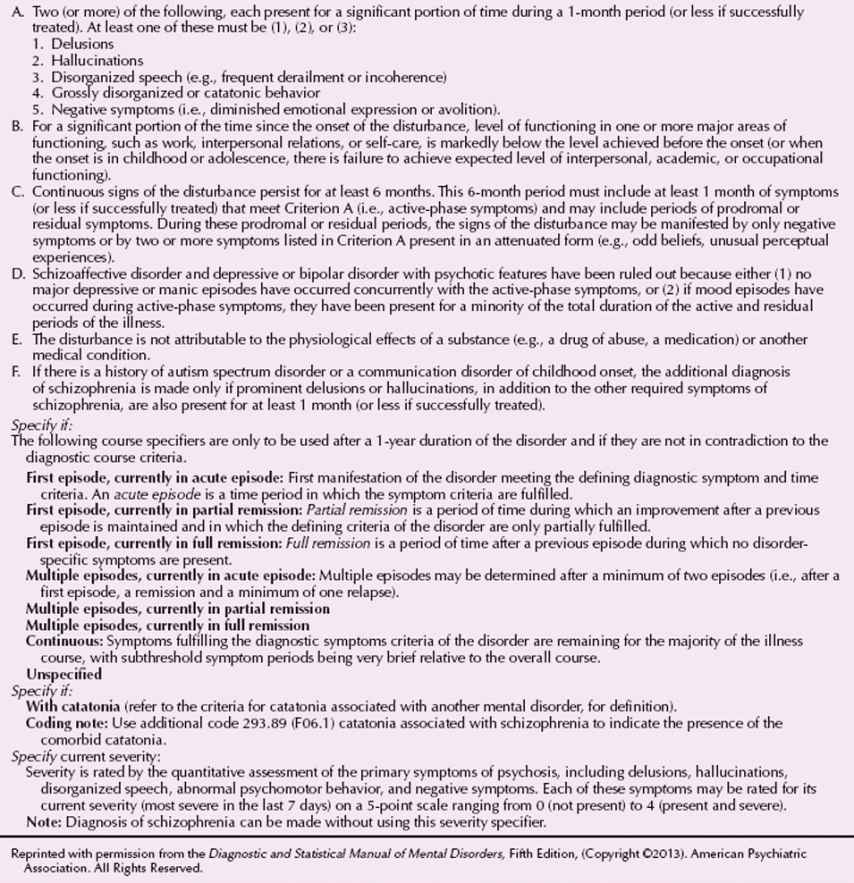

DIAGNOSIS

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria include course specifiers (i.e., prognosis) that offer clinicians several options and describe actual clinical situations (Table 7.1-1). The presence of hallucinations or delusions is not necessary for a diagnosis of schizophrenia; the patient’s disorder is diagnosed as schizophrenia when the patient exhibits two of the symptoms listed in symptoms 1 through 5 of Criterion A in Table 7.1-1 (e.g., disorganized speech). Criterion B requires that impaired functioning, although not deteriorations, be present during the active phase of the illness. Symptoms must persist for at least 6 months, and a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or mood disorder must be absent.

Table 7.1-1

Table 7.1-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Schizophrenia

Subtypes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree