Abbreviations:

% BF= percent body fat

BIA= bioimpedance analysis

BMI= body mass index

CCT= curriculum control trial

CRP= c-reactive protein

CSA= accelerometer

DEXA= dual energy x-ray absorptiometry

FFA= food frequency questionnaire

FU= follow-up

FVI= Fruit and vegetable intake

HE= health education

MVPA= moderate to vigorous physical activity

nRCT= non-randomized controlled trail

OBS= observational

PE= physical education

RCT= randomized controlled trial

SOFIT= System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time

TNFα= tumor necrosis factor α

TSF= triceps skinfold

TVT= television viewing time

WC= waist circumference

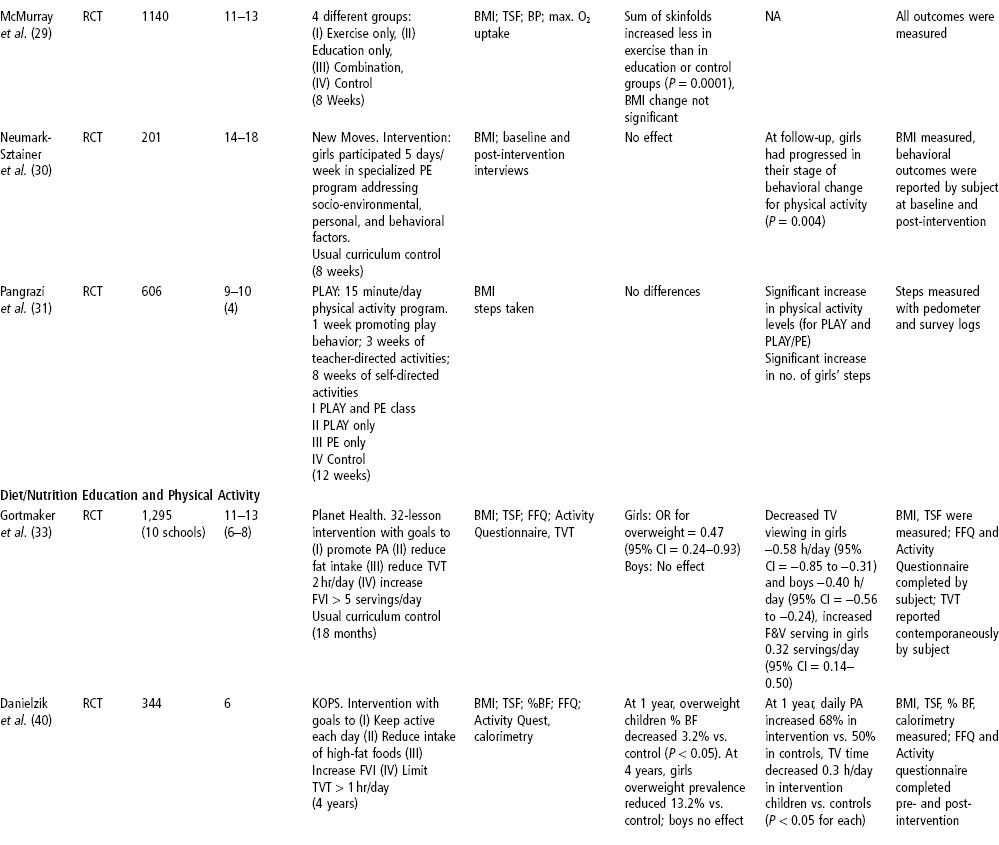

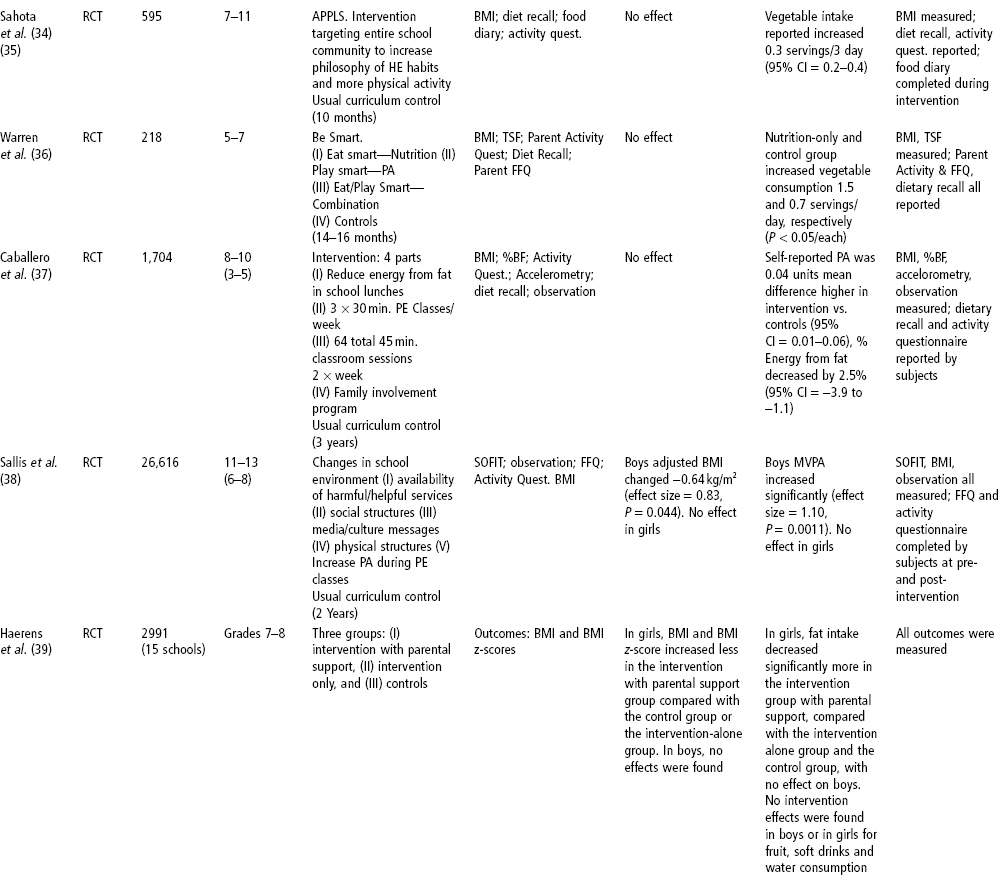

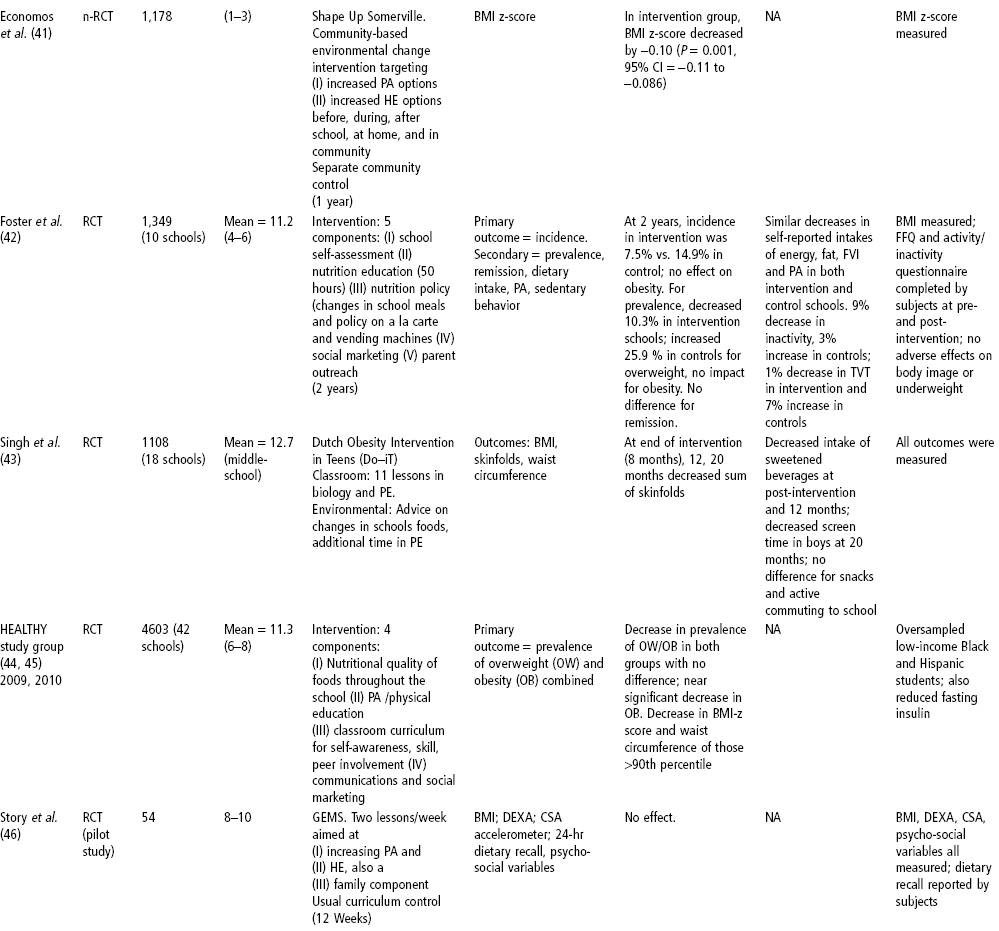

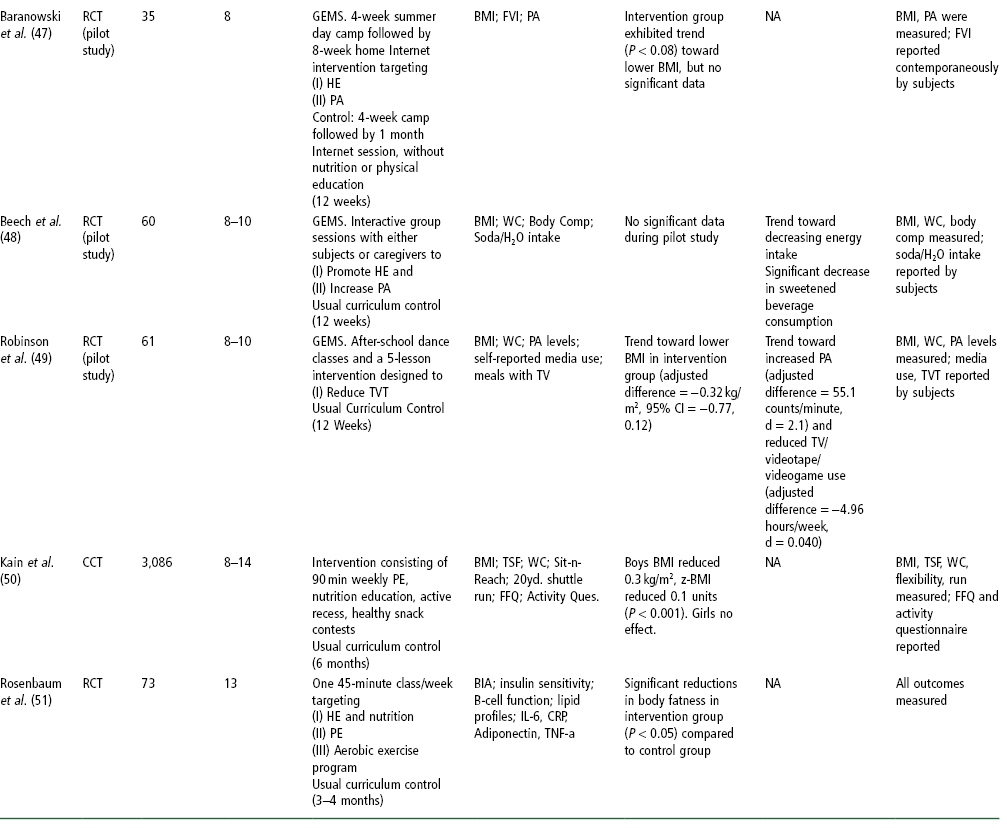

As noted earlier, several meta-analyses have shown interventions that target both diet and/or nutrition education and physical activity to be effective based on some measures of overweight and obesity (21, 22). However, which features of the interventions contribute to effectiveness has remained elusive. In a review of studies, Doak and colleagues (15) found that whether programs were judged to be effective or ineffective based on anthropometric outcomes, they used the following features to some extent: addressing diet and/ or physical activity, targeting the physical or sociocultural environment, addressing individual and family-level factors, and including the parents, teachers, or wider community. The reviewers point out that a purely quantitative comparison may fail to capture differences in the quality of the intervention’s activities: whether educational methods involved active participation of children, or appropriate application of theory, for example.

There may be several reasons for the inconsistency in results among studies. First, there are measurement issues. Studies often used small samples and were hence under-powered. Many researchers also point out that interpreting weight values is itself fraught with difficulties in this population. There are pubertal effects: children are growing at very different rates and with differing stages of developmental changes in body fat content. The use of age- and sex-specific BMI percentile can circumvent some of these problems, but is dependent on accurate measurements of height and weight, calculation of BMI, and plotting of the BMI percentile. In one study based on increasing physical activity (49), there was an increase in BMI simultaneous with reductions in skinfold thickness, a paradoxical finding possibly explained by reductions in subcutaneous fat (accessible to skinfold measures) and increased lean body mass due to exercise.

There are also implementation issues. Most obesity prevention studies published to date have not reported evaluations of how faithfully the intervention was delivered. For studies directed at increasing fruit and vegetable intake or reducing intake of high-fat foods, process evaluation findings show that programs are often not fully implemented as designed. Teachers are more comfortable teaching information didactically rather than engaging students in the motivational and goal-setting activities that are considered a more effective focus of nutrition education curricula. Consequently, even some long-term and comprehensive interventions may not have yielded positive results because the students may not have been receiving the planned “dose” of the intervention. This interpretation is supported by the finding that where the intervention was highly focused and delivered by the investigators rather than by regular teachers or trained laypersons, the impact was significantly positive even when the intervention was short and the sample size was small (51).

It may be that the comprehensiveness, intensity, and duration of interventions, as implemented on site, are not sufficient to overcome the many environmental forces that negatively affect the eating and physical activity patterns of children and youth. Recent studies that have more comprehensively targeted the school’s food and activity environment as well as curriculum have shown some promise. In a year-long intervention that addressed before-, within- and after-school environments and in which the entire community was involved in a highly participatory fashion, the impact was positive (41). It should be noted that many studies did find some improvements in diet and physical activity behaviors, which, if practiced consistently or for long enough, might eventually result in healthy weights or improved body composition. Whatever the reason for the inconsistent results, findings from effective programs, taken together, do not provide clear guidance on specific elements of effectiveness for school-based weight gain prevention programs. While there is increasing recognition of the importance of changing food and physical activity environments to facilitate behavioral change, the evidence suggests that in the school setting, a strong curriculum and rigorous teacher professional development and student engagement are likely highly important.

Future interventions must assess the quality of the implementation and measurements, in addition to the cost and feasibility of delivering such programs on a much broader scale. Identifying effective program components has been challenging, as discussed above. But delivering such programs on a community-wide level to culturally and economically diverse groups of children living in urban, suburban, and rural communities raises daunting issues about program components, training, and the fidelity of program delivery. Rarely do studies include an analysis of the expense of program delivery or the cost of ensuring adequate quality control.

While prior studies suggest that a strong curriculum is needed, they do not offer clear models for how such a curriculum might best be constructed. Thus, many questions remain. How do we teach children about the challenges associated with childhood overweight in ways that are empowering, rather than guilt-inducing? At what grade levels would such an intervention be most effective? How should any intervention program be balanced between helping children understand the problem and helping them act on the problem? Where should the program be housed—in physical education or health or science class? In special assemblies? Or across the regular academic curriculum? If so, how are the activities best coordinated? Would after-school sessions be a better venue given the limited time in the school day? How should parents and families and entire communities participate and support the necessary changes? These questions will only be answered through innovative intervention research.

An Innovative Approach Based on Inquiry-Based Science Education—choice, Control and Change

We developed a curriculum, called Choice, Control and Change, based on the belief that we need to go beyond teaching children which behaviors to enact and the strategies to enact them, to include how to think about food and their behaviors in ways that help them feel competent in navigating today’s food and activity environment. The content of the curriculum focuses on providing an understanding of how biology, the environment, and personal behaviors interact to influence overweight; the process involves inquiry-based science activities to help them understand why they need to take action and behavioral, theory-based strategies for applying learning. The behavioral strategies are based on self-determination (53) and social cognitive (54) theories, which emphasize that behavior is motivated not only by anticipated outcomes but also by a strong sense of personal agency. This sense of personal control and mastery over their own behavior and the ability to create personal food and activity environments we call “competence,” and is enhanced by effective self-regulation skills.

Choice, Control and Change (C3) is an inquiry-based science curriculum made up of 24 sequenced lessons with the goal of improving weight-related behaviors of high risk 6th and 7th graders. C3 is taught by classroom science teachers. The curriculum covers selected national science standards in biology. The development of the C3 lessons used the Stepwise Procedure for Designing Theory-Based Nutrition Education, which involves needs analysis, selecting theory and philosophy, designing activities to enhance motivation (focusing on why to take action) and skills development (focusing on how to take action), and designing the evaluation (55). To increase awareness and enhance motivation—why-to information—the students participate in hands-on investigations that allow them to explore their current views on health and the reasons behind their food and activity choices. Students collect and analyze data in order to increase their understanding of our current food and activity environment, human biology, and their personal behaviors. Students explore how the modern “obesogenic” environment promotes overeating (excessive energy intake) and a sedentary lifestyle (low energy expenditure) through bombarding us, as a society, with opportunities to increase fat and sugar intake cheaply while remaining sedentary. This “mismatch” between human physiology and the modern environment is a factor, perhaps a major factor, in increasing the risk of chronic disease and extra body weight that are plaguing the US and much of the world because maintaining a healthy lifestyle in the modern environment requires a great deal of conscious effort (56–58).

When students come to understand why it is personally important to them to make healthy food and activity choices, they are ready to learn how to enact them. C3 focuses on behaviors that contribute to risk of excessive weight gain over which youth have a large degree of control, such as after-school snack and beverage choices and walking. C3 uses a process of guided goal-setting that has been found appropriate for youth, whereby the curriculum sets out several behaviors, from which youth can choose (59–60). The behaviors are:

- Eat more fruits and vegetables—aim for at least 4 cups a day.

- Drink more water—aim for 8 8oz glasses a day.

- Drink fewer sweetened beverages—aim for no more than 8 oz a day.

- Eat less frequently at fast-food establishments—aim for no more than three times a week.

- Eat fewer packaged snacks—aim for no more than one small or medium a day.

All students are asked to walk more and to take the stairs more often. These behaviors are similar to those recommended for the prevention of child and adolescent obesity (61, 62). Through C3, youth learn that they have choices, can take control and can make changes.

Evaluation of Choice, Control, and Change

The C3 intervention was first pilot-tested several times with 5–7 classes and then formatively evaluated in 19 classes in five schools (about 500 students) using a pre-/post-test design, and analyzed using paired t-tests (63). An impact evaluation was then conducted using a cluster-randomized pre-test/post-test intervention and control group design (64). Ten urban schools from low-income neighborhoods with predominantly African American and Hispanic children were matched in pairs, and then members of each pair were randomly assigned to intervention and control conditions, with 20 classes (504 students) in the intervention condition and 21 classes (534 students) in the control condition. Generally, all the 6th or 7th grade classes in a school participated in the intervention. The C3 curriculum was taught by science teachers on most school days over a period of about 7–8 weeks, interrupted only by assemblies, field trips, and so forth. Some lessons spanned two or more days; thus most classes had 24–35 C3 sessions. Validated instruments measured reported targeted eating and physical activity behaviors and the mediating variables of social cognitive and self-determination theories. Data were analyzed using ANCOVA of post-test scores, with pre-test scores as a covariate. Since the unit of assignment was the school, the data were analyzed with students nested in schools. The primary outcome was whether students reported engaging in the specific behaviors that reduce risk of excessive weight gain that were targeted by the curriculum. The secondary outcomes were changes in the potential mediating variables specified by theory.

In the impact evaluation, students who received C3, compared to those in the control group, reported drinking fewer sweetened beverages and eating fewer packaged snacks, especially candy and salty snacks, and selected smaller sizes. Although they did not reduce the frequency of eating at fast-food restaurants, intervention students reported ordering significantly smaller sizes and ordering value or combo meals less often. The students in the intervention group did not report any significant improvements in fruit, vegetable, or water intake. They reported that they intentionally walked and took the stairs for exercise more often, and spent less time on sedentary activities including watching TV, playing video games or using the computer. Although the data were all self-reported, the fact that some reported behaviors changed significantly while others did not reduces social desirability response bias as the sole explanation of the results. In terms of potential mediating variables, they significantly increased their knowledge, positive outcome beliefs, and self-efficacy about drinking fewer sweetened beverages, eating less frequently at fast-food restaurants, eating fewer packaged snacks, drinking more water, and eating more fruits and vegetables. Outcome beliefs and self-efficacy were found to be mediators that were most predictive of behavior change in a review of studies of fruit and vegetable intake in youth (65). The curriculum also significantly improved their competence and autonomy in the eating and physical activity domains.

The C3 impact study took into account the findings from review of prior studies and thus used a relatively large sample, addressed both diet and physical activity, and paid close attention to implementation issues. To enhance full implementation, research staff provided professional development before implementation and met with teachers each week. Research staff also monitored the degree of implementation by attending and making detailed classroom observations on one third of all lessons. It was found that implementation ranged from 60% to 80%, which is considerably higher than the percentages reported elsewhere (66). The fact that, based on student reports, the intervention had positive effects on students’ sense of competence and on most of the less healthful behaviors targeted by the curriculum and their potential mediators suggests that youth are responsive to an approach that helps them understand that they have choices, can exert control, and can make changes in their eating behaviors and personal food environments to enhance their health and help their bodies do what they want them to do.

Conclusion

The need for effective interventions to reduce the risk of excessive weight gain has never been greater and many approaches have been proposed (8–10). Schools are certainly a rational place for population-based interventions to prevent excessive weight gain in youth. However, specific effective prevention strategies remain elusive. The most useful theoretical frameworks need to be identified (12). A systematic process must be used in designing the intervention, based on a thorough assessment of issues, behaviors contributing to the issues and motivations and skills and appropriate use of theory to develop strategies (55, 65). In addition, with the increased emphasis on academic testing, all obesity prevention curricula must satisfy national or local education standards.

There are also issues related to implementation of research protocols in schools (67–69). Namely, teachers usually implement the curricula; however, they are professionals who have autonomy in the classroom and also have a variety of pressures on them. They may not be able to implement health-related curricula as designed. Yet fidelity to the curriculum as designed is imperative, particularly if successful programs are to be disseminated and implemented in other settings. A fruit and vegetable intervention that proved marginally effective delivered through the regular classroom venue was very effective when the content and strategies were delivered directly to students through the format of a serious educational game (66, 70). Interventions need to be of sufficient duration and intensity and implemented with a high degree of fidelity if they are to be effective. Innovative approaches must also be evaluated.

Our experience shows that science education offers an attractive venue; it is in science class that students can investigate, through inquiry-based approaches, how the body works, and can examine the scientific evidence for why to make healthy food and activity choices. Such an inquiry-based approach can be integrated with cognitive self-regulation strategies on how to take action. In particular, this approach teaches youth how to think about food and their behaviors in ways that are empowering, rather than guilt-inducing, and in ways that help them feel competent navigating today’s food and activity environment and creating healthy personal food environments that will reduce the risk of excessive weight gain. Collection of evidence of the effects of such an approach on weight-related outcomes such as BMI is a necessary next step in this research.

Results from the studies reviewed here suggest that such a classroom curriculum would work best when it is combined with interventions that address the school and larger environment as well (9–10, 41–42, 45, 71–75). Schools need to provide a health-promoting environment in which healthy foods are offered, physical activity opportunities are made available, and school policies reduce barriers to healthful eating and physical activity. It is recognized that such a comprehensive, social ecological approach with all its complexity is difficult to implement and challenging to evaluate (9–10, 55, 76–78). However, the requirement for “wellness policies” in schools in the US and the movement for “health-promoting schools” in many other countries, provide an opportunity for the many stakeholders involved with schools to come together to design and implement such a comprehensive approach. It is clear that when the entire community is involved—from planning to implementation to evaluation—there is greater likelihood of buy-in and hence student outcomes are more likely to be positive and to be sustained (41). National policy documents argue that indeed national social structures, institutions, systems, and policies must also be involved so that food and physical activity environments are supportive of children’s health (8–10, 74–76), as discussed further in Chapter 27. Social norms as well as social structures must become supportive. All the sectors that affect diet and physical activity behaviors must be aligned to achieve such changes—government and industry as well as communities, homes and schools. Many venues will need to be explored and these will require collaboration and coordination. All these actions will require political will. But given the importance of the health of the next generation, as a society we can do no less.

Summary: Key Points

- Schools are a logical place for population-based interventions to prevent excessive weight gain in youth. However, specific, effective prevention strategies remain elusive and the most useful theoretical frameworks need to be identified.

- With the increased emphasis on academic testing, all obesity prevention curricula must satisfy national or local education standards.

- There are challenges related to implementation of research protocols in schools; fidelity to the curriculum as designed is imperative, particularly if successful programs are to be disseminated and implemented in other settings.

- Interventions need to be of sufficient duration and intensity and implemented with a high degree of fidelity if they are to be effective. Innovative approaches must also be explored. Science education may offer an attractive venue.

- Collection of evidence of the effects of any approach on weight-related outcomes such as BMI is a necessary next step in school-based research.

- Studies suggest that any classroom curriculum would work best when it is combined with interventions that address the school and larger environment as well.