chapter 8

Seizures and Epilepsy

This chapter is a brief discussion of the clinical aspects of epilepsy. It does not discuss pathophysiology. The numerous classification schemes [1–4] also are not discussed as it is inevitable that with advancing knowledge these will continue to evolve.

The basic principles of clinical assessment and management of patients suffering from a suspected seizure or epilepsy (recurrent seizures) will be discussed. A comprehensive discussion of epilepsy can be found in numerous textbooks [5–7]. Treatment is documented in Appendix C but, as it will continue to evolve rapidly, any discussion in a textbook will quickly be out of date. Therefore, links to neurology- and epilepsy-related websites are included in Chapter 15, ‘Further reading, keeping up-to-date and retrieving information’. It is anticipated that these websites will provide the reader with the up-to-date information that a textbook cannot provide.

CLINICAL FEATURES CHARACTERISTIC OF EPILEPSY

Epilepsy (apart from the very rare reflex epilepsies discussed below) is:

Epilepsy is an episodic disturbance of function that occurs with variable frequency from a single seizure in a lifetime to many seizures per day. Apart from reflex epilepsy (see ‘Reflex epilepsies’ below), when seizures will occur is unpredictable and can be any time of the day or night and under any circumstances. Some patients may experience a brief warning (aura), lasting seconds only, leading up to the ictus. Unless a patient has more than one type of seizure each episode is identical or almost identical (stereotyped), in terms of the clinical manifestations, to the previous one. If a patient suffers from multiple types of seizures each will be have their own stereotypical features. Seizures are brief, usually lasting less than 1–3 minutes (even tonic–clonic seizures) and rarely 5–10 minutes [8]. There are characteristic positive phenomena, i.e. abnormal movements or smell, taste, sensory, psychic or visual sensations. A loss of function, such as paralysis or sensory loss, is NOT a feature during a seizure but may follow a seizure; this is referred to as Todd’s palsy (see ‘Tonic–clonic seizures’ below).

THE PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH A SUSPECTED SEIZURE OR EPILEPSY

1. Confirm that the patient has suffered a seizure.

2. Characterise the type(s) of seizure(s).

3. Assess the frequency of seizures.

4. Identify any precipitating causes.

6. Decide whether to treat or not.

7. Choose the appropriate drug and dose and monitor the response to therapy.

8. Advise regarding lifestyle.

9. Consider surgery in patients who fail to respond to drug therapy.

10. Decide whether and when to withdraw therapy in ‘seizure-free’ patients.

CONFIRMING THAT THE PATIENT HAS HAD A SEIZURE OR SUFFERS FROM EPILEPSY

In patients with suspected seizure(s) the best history-taking technique is to obtain a blow-by-blow description of the episode or several of the episodes. Concentrate on the periods immediately before, during and after the event or ictus. These are referred to as the pre-ictal, ictal and post-ictal periods. The correct diagnosis depends on establishing the exact duration and nature of the symptoms that occur during each of these three phases. The alternative diagnoses that may be confused with epilepsy have been discussed in Chapter 7, ‘Episodic disturbances of neurological function’.

Useful questions to ask the patient

• What were you doing just before the episode? The circumstances under which the episode occurred may provide a vital clue in terms of aetiology or precipitating factors: flashing lights in a discotheque with photosensitive epilepsy or a seizure during venesection suggesting a seizure probably secondary to syncope.

• Was there any warning? If so, what was the exact nature of this warning and how long did it last? A brief warning or aura lasting only seconds is very typical of epilepsy; a more prolonged warning would point to a possible alternative diagnosis.

• What was your next recollection? Can you establish how long this was after the episode commenced? A short period of lost time, 10 minutes or at most 20 minutes, is more in keeping with epilepsy.

• When you came to were you aware of anything the matter? A period of post-ictal drowsiness or confusion in the absence of a head injury strongly suggests epilepsy.

• Did you injure yourself? This is non-specific, but a dislocated shoulder occasionally occurs with tonic–clonic seizures and an injury indicates a fall, thus reducing the number of diagnostic possibilities.

• During the episode did you bite your tongue or cheek or lose control of your bladder or bowels? These occur with tonic–clonic seizures.

• Have you ever had any unexplained motor vehicle accidents? An explanation may be a seizure without warning.

• When you are watching a television program that you are interested in or having a conversation with a person, do you ever miss parts of the program or conversation? An affirmative answer to this suggests the possibility of minor absence or complex–partial seizures that the patient may not have noticed. However, when patients are just sitting in front of the television it would be not uncommon through lack of concentration to miss parts of the program. On the other hand, if it interrupts a program that the patient is particularly interested in, it is more likely to be a minor seizure.

• Do people accuse you of being a daydreamer? It is not uncommon for children and adolescents to be thought of as daydreamers when they have been having unrecognised minor seizures. It is also not uncommon for children and teenagers to actually daydream, so interpret the answer to this question with caution. If the patient has suffered from repeated episodes, establish if each and every episode was identical or whether there may have been different types of seizures so that detailed questioning of several different events is necessary.

• Have you ever been able to prevent one of these episodes and, if so, how? Seizures secondary to syncope or hypotension may be prevented if the patient assumes a recumbent posture immediately after they experience the first warning.

Useful questions to ask an eyewitness or relative

Some patients can suffer unrecognised seizures for many years [9], particularly children and teenagers who are often thought to be daydreaming. Relatives may have witnessed a number of episodes and not recognised them as seizures.A useful sequence of questions includes:

1. Have you ever seen the patient suddenly interrupt what they were doing and stare into space, where their eyes were open but they did not respond to you? If the answer is yes, this is in keeping with absence or complex–partial seizures.

2. What was the patient doing at the time the episode commenced?

3. What was the first thing that you noticed and how long did it last?

4. What was the next thing that you noticed and how long did it last?

5. What was the next thing that you noticed and how long did it last?

• During the episode was the patient able to hear what you were saying or were they out to it? If the answer is no, this indicates a loss of awareness suggesting a generalised seizure or complex–partial seizure.

• Did you see any excessive blinking or abnormal chewing movements of the mouth? These occur with absence and complex–partial seizures, respectively.

Epilepsy in the elderly

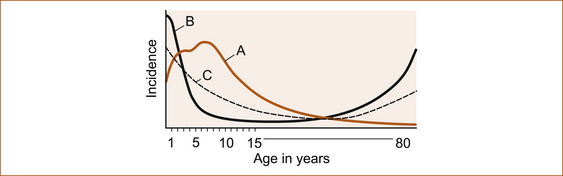

It is a common misconception that epilepsy is a disease of childhood. While this is largely true of absence (petit-mal) seizures, which are very rare in adults and often present when they do occur with absence status epilepsy, seizures do occur in the elderly and the incidence increases with increasing age, as shown in Figure 8.1. Elderly patients with epilepsy most often present with tonic–clonic or complex–partial seizures that have a higher recurrence rate than in the younger population. The complex–partial seizures are often difficult to diagnose since they present with atypical symptoms, particularly prolonged post-ictal symptoms including memory lapses, confusion, altered mental status and inattention [10].

FIGURE 8.1 Schematic diagram to show that both maturational factors in seizure susceptibility derived from onset of age-related epileptic disorders and febrile convulsions (a) and environmental factors derived from age-related risk of cerebral injury (b) combined to yield the incidence of epilepsy by age (c) Reproduced from ‘Seizures and Epilepsy’, by J Engel, Jr. In: Contemporary Neurology Series, edited by F Plum, Vol 31, 1989, FA Davis Company, Figure 5.3, p 115 [12]

Although there is a continuing incidence of seizures throughout life, they are more common in the first 5 years. There is also a higher incidence in the 70- to 80-year-old age group [11].

CHARACTERISATION OF THE TYPE OF SEIZURE

The clinical manifestations of the more common types of seizures is discussed here; more detail can be found in textbooks [12–14]. The commonest seizures in clinical practice are:

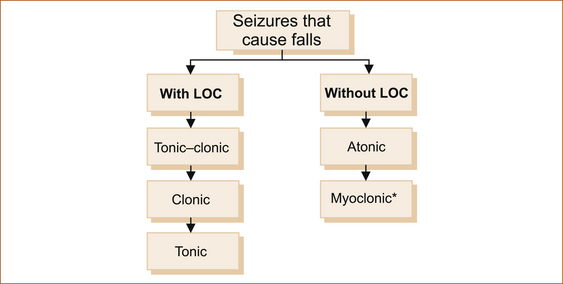

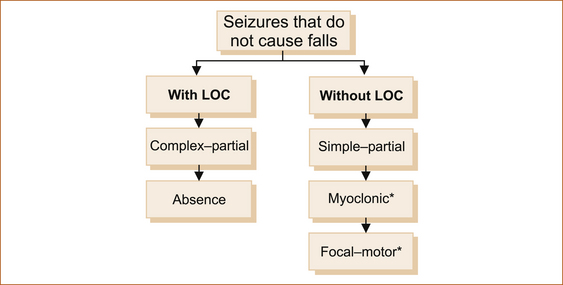

1. seizures that cause the patient to fall with or without loss of consciousness (see Figure 8.2)

2. seizures that are not associated with a fall with or without loss of consciousness (awareness; see Figure 8.3).

Tonic–clonic seizures

• Immediately before ictus: The aura or warning if it occurs may indicate a focal onset such as déjà vu, jamais vu or unpleasant olfactory (smell) or gustatory (taste) phenomena that are suggestive of a temporal lobe origin. The aura may consist of a non-specific epigastric rising sensation, where an unpleasant feeling commences in the epigastrium and rises up towards the head very quickly over a few seconds, a non-specific light-headedness or an odd feeling in the head. Tonic–clonic seizures preceded by an aura are often referred to as focal seizures with secondary generalisation, as opposed to primary generalised epilepsy where the tonic–clonic seizure is not of focal origin. The essential feature is that the aura is identical each time and more importantly is very brief, usually lasting seconds only.

• During ictus: With or without warning (an aura) the patient will fall to the ground, rigid, with the teeth clenched, arms and legs extended and eyes open. At times the arms may be flexed instead of extended. Many eyewitnesses describe the eyes as rolling up into the top of the head, which means that the eyes are open. This tonic phase is brief, usually less than 30 seconds, and it is followed by repetitive jerking (clonic phase) of the arms and legs, which is also brief, usually less than 1 or 2 minutes, although it may be prolonged up to 10 minutes. Seizures may last longer if the patient develops status recurrent seizures without recovery of consciousness between seizures, referred to as status epilepsy. During a tonic–clonic seizure the patient may bite the tongue or cheek, froth at the mouth or be incontinent of urine and/or faeces. If urinary or faecal incontinence occurs, it is during the tonic phase.

• After ictus: Immediately following the seizure the patient is limp, drowsy and confused. This period of post-ictal confusion and drowsiness varies depending upon the duration of the seizure and the age of the patient. If seizures are brief the duration may be less than a few minutes; with more prolonged seizures, the period of confusion can last much longer, usually less than half an hour. In the elderly it may last for several days in the absence of any obvious metabolic or infective process to account for such confusion. Very rarely, paralysis of a limb(s) follows a seizure, an entity called Todd’s palsy. Again, this tends to be more prolonged in the elderly.

Atonic seizures

Drop attacks due to epilepsy mainly occur in childhood; drop attacks that occur in elderly adults are thought not to be epileptic in origin and are discussed in Chapter 7, ‘Episodic disturbances of function’. The Lennox–Gastaut syndrome is seen in childhood and consists of multiple seizure types including atypical absence seizures, myoclonic, tonic–clonic and atonic seizures with often a degree of intellectual disability [5].

Myoclonic seizures

In patients with myoclonic epilepsy, these myoclonic jerks are more frequent, often occur during sleep but characteristically occur first thing in the morning on awakening. They affect the whole body or a single limb and may be single or repetitive jerks. In myoclonic seizures the patient is fully aware of what is happening. There is no aura, loss of awareness or post-ictal confusion, i.e. the patient is normal immediately before and after the event. Myoclonus induced by movement is a feature of post-hypoxic myoclonus [15].

Complex–partial seizures

• Immediately before ictus: The duration of the aura is usually measured in seconds; the symptoms of aura have been described above.

• During ictus: The ictus usually lasts seconds to a few minutes. The patient is not aware of what is happening, nor are they able to respond to any verbal or painful stimuli. In the words of two relatives witnessing minor seizures: ‘the lights were on but no one was at home’ or ‘there were no sheep in the top paddock’. There may be involuntary movements of the mouth or limbs, depending on which area of the brain is the focus for the seizure.

• After ictus: There is a period of post-ictal confusion lasting several minutes during which the patient can usually respond to outside stimuli but is clearly disoriented and confused [18]. The patient is unable to relate what happened during the event.

Absence (petit-mal) seizures

Absence epilepsy generally occurs in childhood and is very rare as a primary presentation in adults. In retrospect, however, when one takes a careful history from a patient with their first tonic–clonic seizure, many patients have had unrecognised absence seizures [9] in childhood and have simply been regarded as either dull or a daydreamer.

• Immediately before ictus: The absence seizure is characterised by no warning unless it is an atypical absence.

• During ictus: The period of impaired consciousness is brief. In one study the average seizure duration was 9.4 seconds (range 1–44 seconds, SD 7 seconds), 26% of seizures were shorter than 4 seconds and 8% were longer than 20 seconds [19]. The patient simply stares into space and may blink, but they are clearly unresponsive to either verbal or painful stimuli. They have no recollection of what happened or was said to them during the episode.

• After ictus: Immediately following the ictus, the patient is able to resume a conversation and the activity that they were undertaking without any post-ictal confusion.

It is surprising how many absence seizures patients can experience without people actually noticing them because they are so brief. Absence seizures can readily be induced by hyperventilation (HV). In one study of 47 children with childhood absence seizures, HV induced seizures in 83% (39/47) of children. Of the eight children who did not have seizures induced by HV, four were too young to perform HV. In the other four children, HV was performed but may not have been performed well [19].

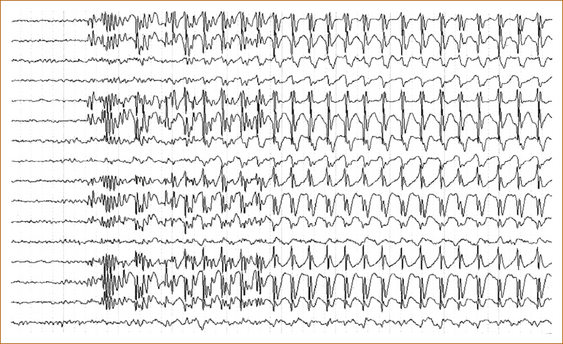

The EEG in absence seizures shows a characteristic 3 per second spike and wave (see Figure 8.4).

Simple partial seizures

The essential characteristic of simple partial seizures is that they can occur at any age in either sex and consist of a brief stereotyped sensation without loss of awareness, i.e. the patient is fully conscious of what is happening and is able to describe the whole episode from start to finish. There is no warning or aura, nor is there any post-ictal drowsiness or confusion. Examples of this type of epilepsy are patients who experience a tingling sensation that may commence in their feet and rise up to the top of the head and sometimes go back down again to their feet, over a matter of seconds.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree