, Jeffrey R. Strawn2 and Ernest V. Pedapati3

(1)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(3)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry Division of Child Neurology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Let us be grateful to the people who make us happy; they are the charming gardeners who make our souls blossom.

—Marcel Proust

In this chapter, we discuss some of the everyday challenges facing the psychotherapist who embarks upon the regular practice of two-person relational psychodynamic psychotherapy. By actively “setting the frame ” for the patient and parents, a psychotherapist starts the psychotherapeutic process on a strong foundation. There is consensus that in most forms of psychotherapy, the psychotherapist benefits by providing an outline of what the patient and his or her family can expect once they agree to participate. It is best to launch the psychotherapeutic process after the psychotherapist sets the frame with the patient and their parents or caregivers so they can have some predictability about what will occur during the process and avoid having surprises when conflict arises.

Many of our practical suggestions, including those on confidentiality, compensation, and time, will be useful to clinicians of any psychodynamic persuasion. However, as we will discuss, there are certain key contrasts between traditional one-person and the two-person relational form of psychotherapy.

In traditional one-person psychotherapy, the frame is clearly set by certain principles. The psychotherapist will attempt to preserve some form of neutrality , provide empathy judiciously, observe for inner conflicts of the patient (as well as those present within the parents), attend for maladaptive defense mechanisms, and infer a patient’s object relations through a child’s play or through verbal interactions in adolescents. Further, frequently missed appointments are generally understood to be a form of an unconscious resistance by the patient or parents.

For the two-person relational psychotherapist, matters are not as clearly defined. The psychotherapeutic process occurs in the intersubjective field, a space that is cocreated by all parties’ subjectivities (temperament, cognition, cognitive flexibility, and implicit relation knowing), including the patient, the parents or caregivers, and the psychotherapist. Each member brings a unique set of nonconscious internal working relational models of attachment on how they implicitly chose to interact with others. Thus, it is quite possible that when the same child and his family are seen by two different relational psychotherapists, a different intersubjective field would be cocreated as a result of the unique sets of temperament, internal working, and implicit relational models of each. An inherent “sloppiness” forms as these intersubjective experiences brush into each other (Chap. 5).

9.1 What to Expect from the Psychotherapist

The following section is intended to succinctly remind the reader of the role the psychotherapist has within the psychotherapeutic relationship as envisioned by two-person relational theory. Though a relational psychotherapist may strive to be empathic, it is more important to recognize that the psychotherapist has a crucial role in the development of the psychotherapeutic process itself. Rather than relying on an approach that “discovers” the patient’s diagnosis or conflicts, the relational psychotherapist must carefully attend to the intersubjectivities in the treatment relationship so as to cocreate interventions that account for the patient’s cognition, temperament, and internal working models of attachment. That is, the inquiry occurs in the form of mutual here-and-now interactions, which allows the psychotherapist to know subjectively the patient’s and their family’s implicit relational models of relating. As an atmosphere of safety sets in, a mutual alliance is created, and new and different information may then be available to the psychotherapist.

For example, there are psychotherapists that are natural at using humor with their patients across a wide range of ages. They may be comfortable using a melodic tone of voice, allowing for a here-and-now mutual subjective experience that facilitates a new emotional experience to unfold in the psychotherapeutic process. Other psychotherapists are less flexible and, although empathic, are somewhat more cautious in their approach toward children, which may not initially provide the atmosphere of safety needed by the patient.

The inquiry of maladaptive patterns is through the active participation by the psychotherapist in the process. To give a broad example, when a family begins to demonstrate conflict during their first appointment and the psychotherapist intersubjectively wants to step in and “join in the conflict,” this becomes a warning sign. It reflects on how the family system nonconsciously seeks to elicit negative interactions from each other, although the family unit outwardly hopes to stop the maladaptive patterns of relating.

9.2 “Setting the Frame”: The Contemporary Diagnostic Interview (CDI)

As we have stressed throughout this book, performing a contemporary diagnostic interview (CDI, Chap. 8) does not necessarily imply a future commitment to begin psychotherapy. Rather, the purpose of the diagnostic interview is to provide a critical form of psychiatric triage and to help guide the patient and family to the best possible setting to fit their needs, which in some cases may not be regular psychotherapy.

We would recommend completing the CDI over the course of two or more appointments if possible. In our experience, this allows the psychotherapist the necessary time to learn about the patient’s and the family system’s strengths and weaknesses. Rather than depending on a verbal history or a review of medical records, the relational psychotherapist must carefully examine the intersubjectivity , which will yield knowledge about the internal working models of attachment and implicit relational knowing. With this information in hand, the psychotherapist can examine the goodness of fit needed to work in a relational psychotherapy approach and embark on the process of providing a new emotional experience in a safe atmosphere.

9.3 “Setting the Frame” in Two-Person Relational Psychotherapy

After the decision has been made and agreed upon by all parties to start an ongoing two-person relational psychodynamic psychotherapy process, it is important to directly address some of the formalities of the treatment relationship.

Many patients and families, especially those who are in treatment for the first time, may not understand the logistics of how psychotherapy works. These parents may be more accustomed to regular doctor visits, such as with a pediatrician or even a psychiatrist for medications, which are quite different in structure and function than a course of psychotherapy. We have laid out important matters that should be discussed with the family before entering into psychotherapy (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

Pragmatic aspects of “setting the frame”

Necessary discussions for establishing a treatment relationship | Discussing the appointment frame | Discussing communication before psychotherapy is initiated |

|---|---|---|

Obtain consent/assent for treatment | Discuss frequency of sessions, including the frequency of parent sessions | Discuss frequency of telephone calls, when the patient should expect return phone calls |

Establish goals of treatment | Discuss time demands with regard to psychotherapy | Discuss voicemail procedure |

Discuss fees and payment | Review cancellation policy (e.g., fees for “no shows”) | Discuss e-mail (and text messaging, if applicable) with regard to HIPAA compliance, confidentiality, etc. |

Assure confidentiality and discuss situations in which confidentiality may not apply (e.g., child abuse, suicidality) | Familiarize the patient with the office, including toys, etc. | Obtain consent for video recording |

Discuss medical records with regard to disclosure | Waiting room and etiquette | Discuss electronic devices with regard to their use in the session |

If medications are a component of treatment, discuss frame (e.g., refills) | Discuss policies regarding “out-of-office” visits | Families as ambassadors for two-person relational psychotherapy |

Provide contact information (see next column) | Special situations |

Consent to Treat

We strongly encourage the child and adolescent psychiatrist and psychotherapist to provide a written contract in the form of “consent to treat ” for the patient and their parents and/or legal caregiver to review and sign, which is then placed in the medical record. This contract should include, but is not limited to, language about the risks and benefits of psychotherapy. Many of the logistical issues of treatment may be spelled out in this document and discussed with the patient and family in an organized fashion. Relying on verbal exchanges may lead to misunderstandings and disrupt the overall psychotherapeutic process, which may be particularly frequent in persons with temperamental difficulties, cognitive weaknesses, or disorganized attachment styles.

The reader is strongly advised to have his or her personal attorney review any legal document before he or she implements a binding document. There are a wide variety of business practices among child and adolescent psychiatrists and psychotherapists that include differences in payments (e.g., self-pay, insurance), treatment settings (e.g., academic, community based, private), and emergency availability. There are also many state and local regulations and laws that govern certain institutional settings, such as hospitals and mental health clinics, that are different than those governing a private practitioner.

Goals of Treatment

After the CDI, the psychotherapist should be able to share his or her initial goals with the patient and family and ask if the goals are consistent with their expectations. The most important goal of a two-person relational psychodynamic psychotherapy will be to provide the child or adolescent with the opportunity to develop a healthier sense of self and more adaptive patterns of social reciprocity—ability to love, play, and learn.

Working with Parents

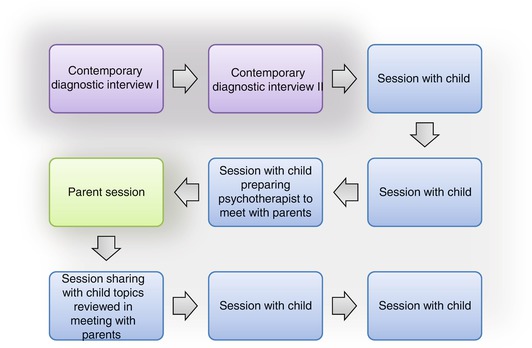

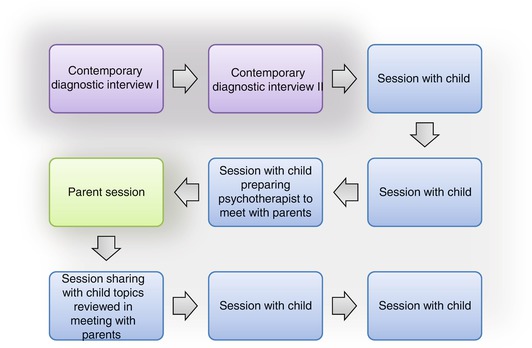

In our experience, working with parents regularly is essential. We recommend that the psychotherapist schedule appointments with the patients’ parents individually after every three to four sessions with the child or adolescent. This provides the parents or caregivers a sense of relief in knowing that they will have time to speak to the psychotherapist after he or she has become more familiar with their child or adolescent. In preparation for meeting with the parents, it is important to ask the child what they think should be shared with the parents about their work together and whether they have ideas about what the parents may be asking the psychotherapist. Asking the patient to be a contributing participant in the parent session without being present is a valuable model of the new adaptive ways of trusting others, which is stored in the patient’s implicit nondeclarative memory. Then, after meeting with the parents, it is helpful to review with the patient what had been discussed with the parents (Fig. 9.1).

Fig. 9.1

Suggested course of two-person relational psychotherapy

It is expected that some disagreements will occur among the patient and the parents as a result of these meetings, and this will likely occur more frequently in families that have poor internal working models of relating with others to begin with. Their disagreements should be considered as an example that the process is beginning to serve the cocreation of new adaptive ways of relating—communication rather than isolation or distancing—that the psychotherapist has influenced. Oftentimes, their disagreements are the result of their desire to collaborate in helping to achieve the goals set out when the process began, although early in the process they will continue to be influenced by maladaptive relational patterns.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree