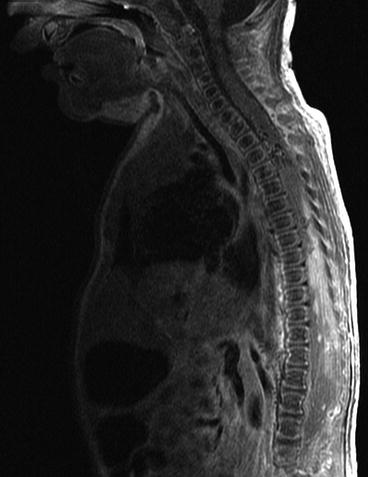

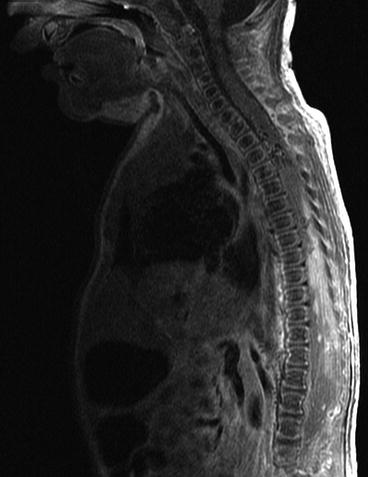

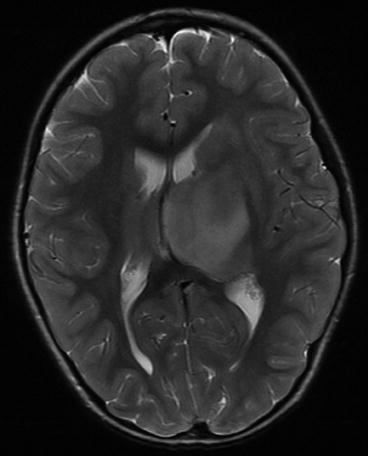

Fig. 7.1

MRI of high thoracic myelomeningocele

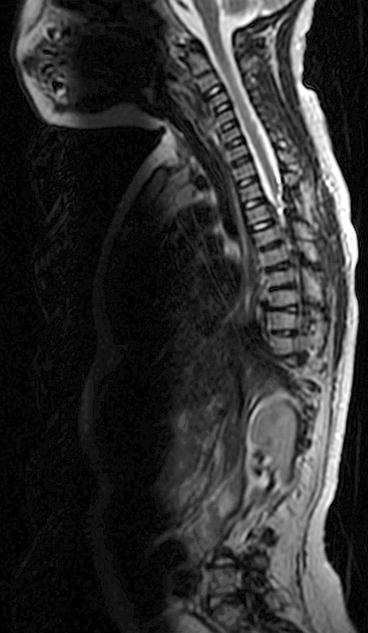

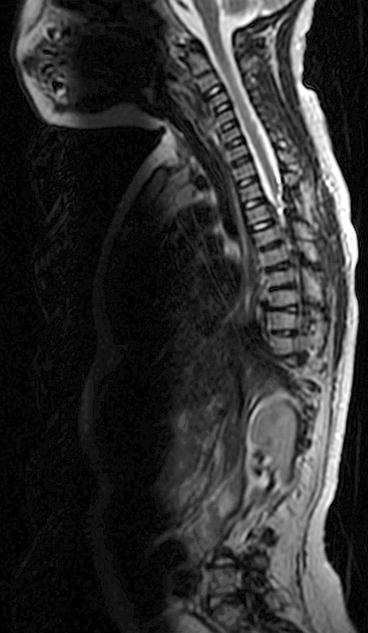

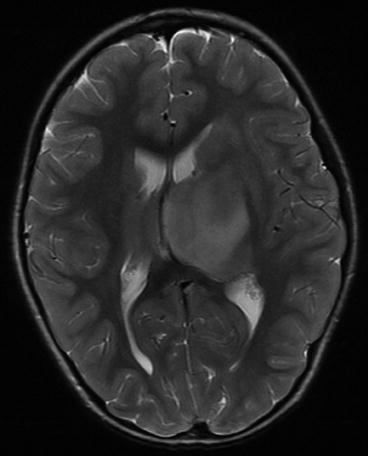

Fig. 7.2

MRI showing massive hydrocephalus

Fig. 7.3

Closure of the defect with rotation flaps and split skin techniques

Seven years later, she is living with her family (Fig. 7.4). Although she is a cooperative and attentive girl, she is cognitively very challenged, needing special school. She can speak words and short sentences and is wheelchair dependent, but can play by herself. Concerning transfers, she is almost completely dependent and she also needs to be catheterized six times a day. Up till now, she has needed ten operations.

Fig. 7.4

The girl at the age of 7 at home (printed with permission of her parents)

7.2.2 Case 2 (A Boy with a Huge Intramedullary Tumor)

At birth, this boy appeared to have paraplegia at a high thoracic level. MRI revealed a huge intramedullary tumor extending from the upper thoracic region down to the sacral region (Fig. 7.5). Biopsy revealed a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Six months after birth and after many multidisciplinary deliberations and following consistent requests of the parents, it was decided to operate the boy and remove the tumor en bloc by a spinal cord transection just below the normal cervical spinal cord and a resection of the distal cord together with the dural sac and all the roots (Fig. 7.6). Surgical removal was followed by systemic chemotherapy (three cycles of vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide).

Fig. 7.5

MRI of large intramedullary tumor extending from the upper thoracic level

Fig. 7.6

MRI after en bloc resection of the tumor below the cervical spinal cord

At the age of 7, he remains in remission. He grew up as a short-statured wheelchair-dependent boy. He has feeding problems, which necessitate PEG tube feeding. Arm function is normal, but he is completely paraplegic. Because of a neurogenic bladder, he needs to be catheterized four times a day. He is attending normal school, and despite his physical condition and dependency, up till now, he is seldom frustrated by his handicaps.

7.2.3 Case 3 (A Young Girl with an Anaplastic Glioma)

At the age of 4½ years, this girl was admitted to the hospital with progressive right-sided hemiparesis. MRI scan revealed a large thalamic tumor (Fig. 7.7). Biopsy revealed a highly malignant glioma. Subsequently, the girl was operated. A transcallosal approach was performed which resulted in a partial resection of the tumor. Postoperatively she was aphasic but cognitively preserved. Systemic chemotherapy was started (VP16 and carboplatin), but follow-up MRI showed again an aggressive tumor growth. A second operation was considered to be disproportionate by the medical team, but the parents urgently requested to do anything to prolong her life. Two months after the initial operation, the young girl underwent partial resection of the recurrent malignant glioma. The occurrence of progressive hydrocephalus required a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. After the second operation, 30 days of radiation therapy followed, each time under general anesthesia because of her young age.

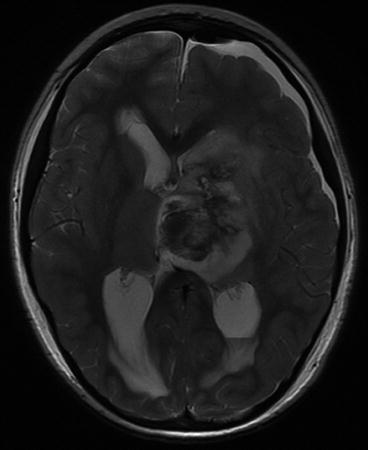

Fig. 7.7

MRI of diffuse thalamic anaplastic glioma

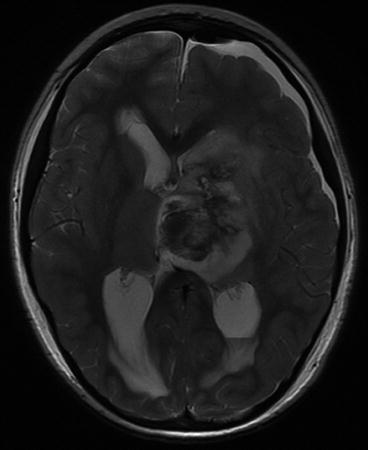

For a few months, she did moderately well, but gradually, she developed severe neurological deficits. MRI revealed a huge recurrence of the tumor (Fig. 7.8). Palliative treatment was started and she died at the age of almost 5½ years.

Fig. 7.8

MRI showing regrowth of the tumor after surgical debulking and chemotherapy

7.3 Discussion

7.3.1 “Inappropriate” Neurosurgical Interventions

An appropriate neurosurgical intervention is adequate, timely, and proper following moral standards and codes of the profession. Inappropriate neurosurgical interventions therefore can be defined as “not proper or untimely” use of neurosurgery. Inappropriate neurosurgical interventions include disproportionate neurosurgical interventions such as “excessive, too much, or more than enough” but also as “not enough” and even “futile use of neurosurgical interventions.”

7.3.2 “Disproportionate” Neurosurgical Interventions

Proportionate neurosurgical interventions could be defined as interventions that reduce patient’s risk of death in acute and life-threatening conditions or improve or restore the quality of life by avoiding long-term physical or mental sequelae. Disproportionate neurosurgical interventions are perceived by most healthcare providers, patients and their relatives, and/or society as disproportionate and/or out of balance, in relation to the condition of the patient or the expected outcome or reduction in risk of death of the patient or quality of life.

Neurosurgical treatment can be “not enough” in terms of inadequate treatment. Inadequate treatment can take place due to inadequacy of the physician, for financial reasons (especially in low-income countries), or at the explicit request of the patient or caretakers. More prevalent, disproportionate neurosurgical interventions are judged by physicians, nurses, patients, relatives, or society as “too much” or “more than enough.” In a small proportion of the cases, the inappropriate neurosurgical treatment can be judged as futile, in the sense of being ineffective or pointless.

Pearl

Converse to earlier bioethical writings, the use of the terms inappropriate or disproportionate neurosurgical treatment would be better than futile treatment as a reflection of the actual situation.

7.3.3 Medical Futility

Medical futility as a concept and the use of the term “futile care” are controversial and troublesome. Futile care can be defined as the initiation or prolongation of “ineffective, pointless, or hopeless” use of neurosurgical treatments. Therefore, medical futility is by definition inappropriate care. However, the inappropriate or disproportionate uses of neurosurgical interventions do not necessarily need to be futile. An example of medical futility would be the use of mechanical ventilation in a brain-dead patient who has declined to be a donor. Medical futility by this definition is rather rare in neurosurgery.

7.3.4 Disproportionate Use of ICU Resources in the Sense of “More than Enough”

Other than the patient her/his relatives can judge the use of neurosurgical interventions to be “more than enough” if it is not in the patient’s best interest. Physicians involved in the care of patients with severe neurological conditions should question themselves if there are medical interventions used in these patients that they can label as disproportionate because they, the nurses, or relatives of the patients are sufficiently confident that the interventions will not be beneficial. Excessive resources are sometimes used to provide life-sustaining medical care in debilitating conditions. Especially in older patients and in patients with multiple comorbidities, this could be labeled as “too much” or “more than enough.” Because we have the possibility and the resources to postpone and orchestrate death for a sometimes indefinite time, we have the moral responsibility to deliberate with all professionals involved and the patient and/or relatives, whether the continued care is still in the best interest of the patient. Alternatively, we should question ourselves whether initial institution of neurosurgical care is in the patient’s interest.

7.3.5 Disproportionate Use of Neurosurgical Interventions in the Sense of “Too Much”

When the initiation or prolongation of neurosurgical interventions is not anymore in the patient’s best interests, “too much” and thus disproportionate care is delivered. This occurs when the condition of the patient is irreversible or has become irreversible during the course of neurosurgical intervention according to current knowledge, as in the following circumstances:

(a)

No effective treatment is available or the prolonged treatment has no real pathophysiologic rationale anymore.

(b)

Effective treatment is available; however, the patient is not responding to therapy (“a nonresponder”), even when treatment is at its maximal level and it is not plausible anymore to assume that cure will occur.

(c)

Effective treatment has already been given to the patient with no or only minimal response (“a minimal responder”; marginally effective interventions).

(d)

It is certain or nearly certain that the treatment will not achieve the goals that the patient or the parents have specified or is against the patient’s or parents’ will (e.g., in patients with advanced directives).

7.4 Analysis of the Three Cases

7.4.1 Case 1 (Is Surgical Treatment Appropriate in a Large Thoracic Myelomeningocele?)

Directly after birth, the multidisciplinary MMC team was uncertain concerning what to do. Some members considered closing of such a large defect as disproportionate in the sense of “too much.” Furthermore, before the birth of the girl, the parents were told that their child would be stillborn or would die soon after birth. So why not let the baby die? Was not that perhaps in her best interests? But the girl was not stillborn and did not die soon after birth resulting in the situation in which the parents urged consistently and repeatedly to do everything possible to save the life of their child. The child herself appeared to be in a reasonable state, as no intensive care was necessary and the Comfort and VAS scores were most of the time below threshold. Finally, closing the defect was considered as an appropriate treatment to achieve two goals: to diminish the discomfort being caused by the huge MMC and to prevent a possible life-threatening complication (i.e., a fulminant meningitis). The decision was also made following the assumption that the parents loved their child and would be able to offer competent care should the girl survive. The operation itself would only harm the patient by causing wound pain for a limited period of time which was expected to be treatable effectively using standard pain medication.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree