Sexuality and Sexual Disorders in Women

Rosemary Basson

In cultures where women’s sexual pleasure and wish to engage sexually are endorsed, there are increasing data on the nature of their sexuality, sexual function, sexual problems and dysfunction, and the prevalence of genital pain with sexual activity. However, in cultures where sex is considered from the perspective of the man’s pleasure only and the woman’s need, preferences, function, enjoyment, and orientation are ignored, we clearly remain ignorant. The picture presented in this chapter is, therefore, far from complete. Seventy-six percent of 3,300 recently surveyed North American women considered sex moderately or very important; Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic women were more

likely to deem sex intensely important than were women from China or Japan (1). Of another 987 North American women recently surveyed, 24% reported marked distress about their sexual relationship or their own sexuality or both (2). Thus problems that interfere with this important aspect of women’s lives warrant careful assessment and management.

likely to deem sex intensely important than were women from China or Japan (1). Of another 987 North American women recently surveyed, 24% reported marked distress about their sexual relationship or their own sexuality or both (2). Thus problems that interfere with this important aspect of women’s lives warrant careful assessment and management.

CHARACTERISTICS OF WOMEN’S SEXUALITY

THE SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE IS PARAMOUNT

Determinants of women’s distress about their sexual relationships and about their own sexuality have recently been studied (2). The subjective response, defined as feeling emotionally close to her partner, feeling pleasure, not feeling displeasure, or feeling indifferent, had the most significant effect of a number of variables. This applied to women’s distress regarding both their sexual relationships and their own sexuality. Interestingly, distress about their physical sexual response had a weaker effect on distress about their relationship and no significant effect on distress about their own sexuality. It is therefore possible that relationship problems themselves impair physical response. It was apparent that younger women were more likely to be distressed if they had problems responding physically, but this still only caused distress about their respective sexual relation-ships—not about their own sexuality.

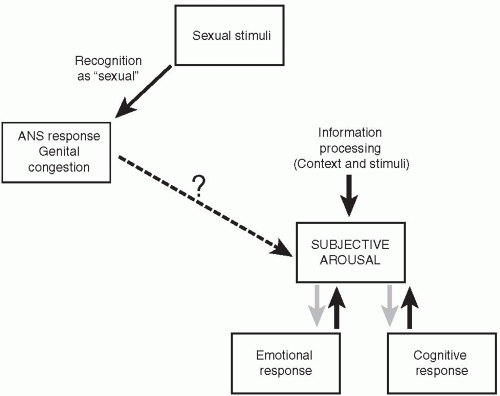

Emotions during sexual engagement strongly impact women’s overall subjective sexual experience, including the composite entity of sexual arousal. Sexually healthy women show highly variable correlation between their subjective arousal and psychophysiologic measures of genital congestion. Such testing involves the woman watching an erotic movie in a private room, while a tamponlike device she has inserted into her vagina records physiologic increase in congestion of blood around her vagina as she views the film. Both sexually healthy women and women reporting chronic low sexual arousal can show prompt genital congestion in response to the erotic video even if they report minimal subjective arousal. In women with chronically low arousal, the video may produce negative affect such as anxiety. Paradoxically, the intensity of this negative affect correlates with the degree of genital congestion. Figure 15.1 is a model of subjective sexual arousal.

Thus, for many women complaining of lack of sexual arousal, there is an apparent “disconnection” between the genital response (prompt and physiologic) and subjective excitement/arousal (absent). The degree to which such women are aware of the genital changes resulting from sexual stimulation varies. Thus some are well aware of an increase in vaginal lubrication despite the absence of any sexual excitement.

For sexually healthy women, marked lubrication may well excite a male partner and indeed may reassure the woman that her response is healthy, but of itself, lubrication rarely affords excitement to the woman. Indeed, in many sexually healthy women, their arousal is more strongly modulated by emotions than by genital feedback. Sometimes physicians see women who complain of excessive lubrication with stimulation, something that causes them embarrassment and displeasure.

Brain studies by functional magnetic resonance imaging of women during sexual arousal show activation of areas involved in cognitive appraisal and areas involved in emotional response as well as areas involved in the organization and perception of genital reflexes. In contrast to findings in similar studies in men, the uptake in the latter areas (including the posterior hypothalamus and rostral

anterior cingulate) does not correlate closely with the woman’s subjective arousal (4).

anterior cingulate) does not correlate closely with the woman’s subjective arousal (4).

WOMEN HAVE MANY REASONS FOR ENGAGING IN SEX

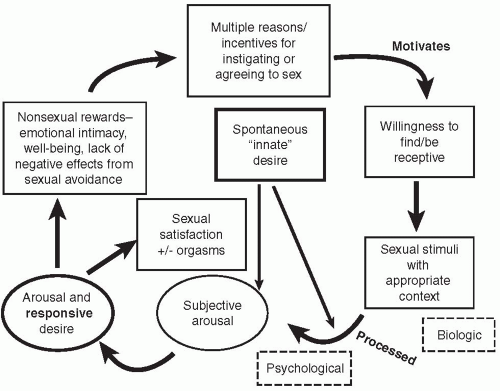

Most studies of women’s sexual motivation have been of women in established relationships. Interestingly, for the majority of these women, sexual desire itself is not a frequent reason to initiate or agree to partnered sexual activity (5,6,7). Frequently cited reasons include increasing her emotional closeness with her partner and enhancing the woman’s own sense of well-being as well as avoiding negative consequences of lack of sexual activity in the relationship. Initially she is sexually neutral but willing to become imminently aroused, but only well into the experience does she sense sexual desire. This type of response appears familiar to women. It is clear that providing the experience is enjoyable and the outcome rewarding, women find the experience entirely satisfactory (Figure 15.2).

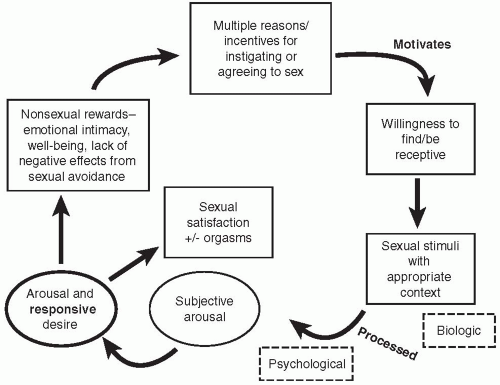

Sometimes response is augmented or overshadowed by a sense of apparently spontaneous desire, as shown in Figure 15.3. This progression from desire to arousal to orgasm and resolution reflects the original model by Kaplan, Masters, and Johnson.

Cross-cultural study is needed to substantiate the clinical impression that women from some cultures focus strongly on a wish to please the partner as their major motivation. Baseline data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the

Nation (SWAN) (1) show no marked cultural differences in the percentages of women choosing among three sexual motivations in response to a question on reasons for engaging in sex: expressing love, meeting the partner’s sexual needs, lessening their own tension and stress. There are minimal data on lesbian women’s reasons or incentives for sexual activity in long-term relationships, where sexual frequency is known to be generally lower than for women in heterosexual relationships. The clinical impression is that as both partners have relatively infrequent spontaneous sexual desire (compared to most men), there is no need for either woman’s sexual motivation to be based solely on wanting to meet the sexual needs of the partner.

Nation (SWAN) (1) show no marked cultural differences in the percentages of women choosing among three sexual motivations in response to a question on reasons for engaging in sex: expressing love, meeting the partner’s sexual needs, lessening their own tension and stress. There are minimal data on lesbian women’s reasons or incentives for sexual activity in long-term relationships, where sexual frequency is known to be generally lower than for women in heterosexual relationships. The clinical impression is that as both partners have relatively infrequent spontaneous sexual desire (compared to most men), there is no need for either woman’s sexual motivation to be based solely on wanting to meet the sexual needs of the partner.

FIGURE 15.2 • Sex response cycle initiated for reasons other than desire. Adapted from Basson R. Obstet Gynocol 2001; 98:350-353. Used with permission from Elsevier. |

THE PHASES OF SEXUAL RESPONSE ARE NOT DISCRETE

The models of women’s sexual response mentioned above illustrate the overlap of desire and arousal and the lack of any one linear sequence of phases. Additionally, women report merging of the phases of arousal and orgasm. Indeed, orgasm can be multiple and experienced at different levels of intensity of arousal. Orgasms themselves can be discrete events of a few seconds or a prolonged plateau of intense orgasmic excitement lasting more than 30 seconds as originally described by Masters and Johnson. The lack of a refractory period in women allows the potential for prolonged sexual activity in overlapping phases of varying sequence.

WOMEN’S SEXUALITY IS DISCONTINUOUS

Normally during pregnancy, there is reduced sexual desire and infrequent sexual intercourse. These reductions have been related to women’s fears about causing miscarriage earlier in the pregnancy or harm to the fetus from intercourse or orgasm at any stage in the pregnancy. Other reasons women cite are physical discomfort, fatigue, or feeling less physically attractive or less sexually desirable than before pregnancy.

A recent survey of 570 women and 550 of their partners showed that an average couple resumed intercourse and nonpenetrative sex by about the seventh week postpartum (9). Women who were breast-feeding reported less sexual activity and less satisfaction. There were no marked differences according to method of delivery, although women who delivered a child by cesarean section were more likely to have resumed intercourse at one month postpartum than were women who had delivered vaginally. Presence or absence of episiotomy or tear was not recorded in the study.

A modest gradual decline in sexual desire, interest, and responsivity occurs with menopause and aging (10). Frequency of partnered sexual activity may or may not decrease given that women have many reasons to engage in sex other than desire. Increased desire and interest are consistently reported with new relationships even many years after the menopause (10).

WOMEN’S SEXUALITY IS CONTEXTUAL AND MAY BE ADAPTIVE

As reflected in the model of women’s sex response (Figure 15.2), motivation to be sexual and the mental processing of sexual stimuli are affected by both the larger context of the woman’s life and the immediate context of the potential sexual experience. Longitudinal (10) and cross-sectional (11) menopausal studies

have confirmed the importance of a woman’s feelings for her partner in determining her sexual appetite and responsivity. Her relationship with others, the demands of those relationships, and her positive or negative feelings about them, as well as societal standards and the influence of poverty (12,13), can affect both her motivation and sexual arousability. Specifically, feelings for her partner at the time of sexual interaction and her present stated emotional well-being were the strongest predictors of sexual distress in the recent North American National Probability Sample (2). It has been noted how relatively infrequently women engage in sex for reasons of desire; rather, the stimuli and an appropriate context of the occasion can move the woman from sexual neutrality to sexual responsiveness. Women’s lack of sexual responsiveness in problematic contexts may be considered a normative adaptive response that can be construed as healthy rather than unhealthy; to consider this as a dysfunction or disorder may well be inappropriate (2). However, the woman may report that she is experiencing lack of sexual pleasure, dyspareunia, or is disinterested in engaging in sex. Labeling such problems “dysfunction” need not imply something intrinsically wrong with the woman’s sex response system. Analogously, a woman with tension headaches due to an ergonomic problem with her chair and computer desk need have no intrinsic musculoskeletal abnormality of her neck but will receive a medical diagnosis nevertheless.

have confirmed the importance of a woman’s feelings for her partner in determining her sexual appetite and responsivity. Her relationship with others, the demands of those relationships, and her positive or negative feelings about them, as well as societal standards and the influence of poverty (12,13), can affect both her motivation and sexual arousability. Specifically, feelings for her partner at the time of sexual interaction and her present stated emotional well-being were the strongest predictors of sexual distress in the recent North American National Probability Sample (2). It has been noted how relatively infrequently women engage in sex for reasons of desire; rather, the stimuli and an appropriate context of the occasion can move the woman from sexual neutrality to sexual responsiveness. Women’s lack of sexual responsiveness in problematic contexts may be considered a normative adaptive response that can be construed as healthy rather than unhealthy; to consider this as a dysfunction or disorder may well be inappropriate (2). However, the woman may report that she is experiencing lack of sexual pleasure, dyspareunia, or is disinterested in engaging in sex. Labeling such problems “dysfunction” need not imply something intrinsically wrong with the woman’s sex response system. Analogously, a woman with tension headaches due to an ergonomic problem with her chair and computer desk need have no intrinsic musculoskeletal abnormality of her neck but will receive a medical diagnosis nevertheless.

This concept that the environment affects function is basic to the understanding of sexual physiology as well as nonsexual physiology. The tendency in the past to consider etiologies of dysfunction as either biologic or psychological has little scientific foundation. Rather, there are numerous examples of environmental stresses interacting with physiology, as with the immune and hormonal systems, and even areas of the brain—in particular the hippocampus, which can change in volume according to stress levels. Interestingly in female oophorectomized rodents, environmental influences (a male animal in adjacent cage) and past experiences, including conditioned responses, can cause the same increase in sexual behavior afforded by the administration of sex hormones (14).

Physical health and physical well-being also have an impact on sexuality. Disease processes (e.g., spinal cord injury) may directly interfere with sexual response, but many other connected factors are involved as shown in Table 15.1.

TABLE 15.1 Areas of Chronic Illness Potentially Impacting on Sexual Health | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Specific studies focused on women receiving radical hysterectomy for cancer of the cervix have found a definite possibility of autonomic nerve damage affecting vaginal and vulval sexual response. Some prospective studies failed to confirm the results of a previous retrospective cross-sectional study that reported reduced vaginal lubrication and elasticity after hysterectomy (15). A recent prospective study of 173 women with early-stage cancer of the cervix treated by radical hysterectomy involved surgeries where the incisions in the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments were deliberately placed to spare traversing autonomic nerves that supply the vagina and vulva (16). Problems with sexual response were common in the first few months postoperatively but, nevertheless, sexual interest remained. By two years, sexual response had definitely improved, but both the women and their partners reported lessening of sexual interest. Only 10% of the women complained of significant lubrication difficulties at the two-year mark. The study did not inquire into congestion and pleasurable sensitivity of the vulval structures. Women with cancer of the cervix may also be subjected to marked hormonal changes from surgical oophorectomy or radiation damage to the ovaries. They may or may not receive estrogen therapy. In addition, there are many nonmedical factors involved, given that these women face a potentially life-threatening illness, which perhaps explains the lack of a simple correlation between sexual difficulties and treatment-induced changes whether hormonal, neurologic, or structural.

Diabetes, with its potential to impair endothelial function and autonomic nerve conduction, might be expected to directly affect genital sex response through lack of genital engorgement and lubrication and through anorgasmia. These outcomes have not been found in studies to date. Except for the entity of vaginal lubrication in one large outpatient study (17), psychological rather than somatic factors have largely accounted for women’s sexual complaints across studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree