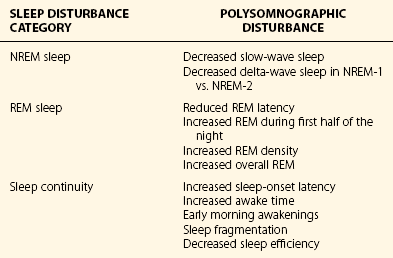

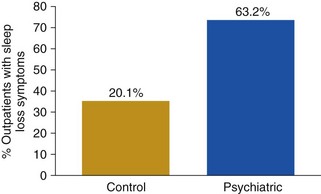

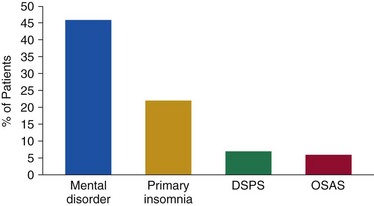

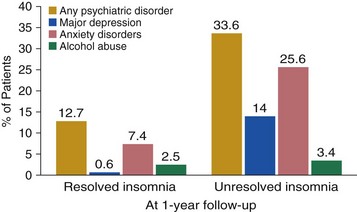

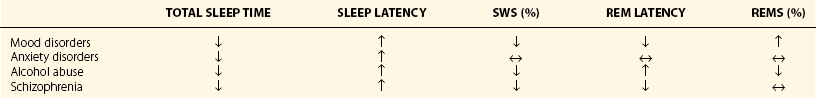

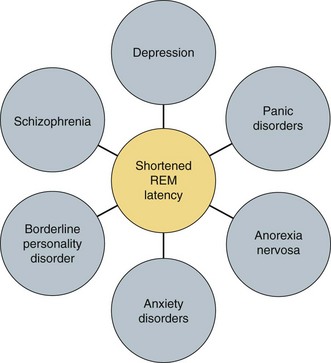

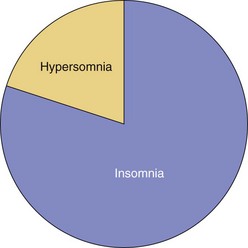

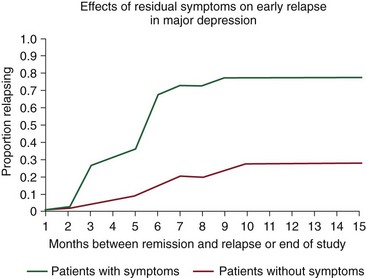

Chapter 17 Common sleep problems such as insomnia, circadian rhythm disorders, and nightmares reviewed elsewhere in this volume occur very frequently in patients with psychiatric illness. Up to 63% of patients with psychiatric illness report significant sleep loss compared with only 20% of the general population (Fig. 17-1). Conversely, disturbed sleepers report more psychiatric symptoms than do undisturbed sleepers. Nearly 45% of patients with insomnia can attribute their sleep loss to psychiatric conditions. Less common causes are primary insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and other medical disorders (Fig. 17-2). Figure 17-1 Prevalence of insomnia in psychiatric patients compared with patients who do not have psychiatric illness. (Data from Sweetwood HL, et al: Sleep disorder and psychobiological symptomatology in male psychiatric outpatients and male nonpatients. Psychosomat Med 1976;38:373-378.) Figure 17-2 Prevalence of insomnia associated with mental illness, primary insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), or other medical illness. (Modified from Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3d, Hauri PJ, et al: Diagnostic concordance for DSM-IV sleep disorders: a report from the APA/NIMH DSM-IV field trial. Am J Psychiatry 151:1351–1360, 1994.) In some patients, insomnia may even be a harbinger for future mental illness. In approximately a dozen studies, it has been shown that unresolved insomnia increases the odds of developing a new psychiatric disorder over the following year, particularly a major depressive episode (MDE) or panic disorder (Fig. 17-3). It is unclear whether insomnia is merely an early symptom of MDE or a modifiable risk factor, but the evidence tilts toward the latter. In susceptible patients with bipolar disorder, even a single night of sleep loss has been shown to precipitate manic symptoms. Figure 17-3 Percentage of patients with insomnia who return after 1 year, with resolved or unresolved insomnia, and those with a new diagnosis of psychiatric illness. (Data from Ford DE, Kamerow DB: Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA 262(11):1479–1484, 1989.) Objective abnormalities in sleep architecture recorded by polysomnography (PSG) have been noted in patients with psychiatric disorders. In healthy adults, sleep onset occurs approximately 10 to 15 minutes after lights out, followed by stages 2, 3, and 4 of non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. This is followed by a period of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. This cycle of NREM-REM sleep occurs at approximately 90- to 100-minute intervals throughout the night. The duration of NREM sleep progressively decreases throughout the night, whereas REM sleep duration increases. Intermittent awakenings of short duration occur in healthy adults but generally last for only 2% to 5% of total sleep time. Specific sleep pattern anomalies are associated with psychiatric illness. In particular, decreased REM latency has been notably associated with a number of disorders, including MDE, panic disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and borderline personality disorder (Fig. 17-4). Other specific patterns of PSG abnormalities have been associated with depression, PTSD, anxiety, alcohol dependence, and schizophrenia (Table 17-1). Table 17-1 Polysomnographic Features of Mood and Anxiety Disorders, Alcohol Abuse, and Schizophrenia ↓, decreased; ↑, increased; ↔, no change; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; SWS, slow-wave sleep. Data from Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, Gillin JC: Sleep and psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatr 49:651–668, 1992. Figure 17-4 Shortened rapid eye movement (REM) latency is associated with a number of psychiatric conditions. Disturbed sleep occurs in at least 80% of patients with major depression (Fig. 17-5). Higher levels of insomnia correspond to a significantly greater intensity of suicidal thinking. In fact, insomnia is a better predictor of near-lethal suicide attempts than a specific suicide plan. Insomnia is the most frequent residual symptom during remission in patients treated for depression. In addition, patients in remission who experience continued sleep disruption have a higher rate of major depressive disorder relapse (Fig. 17-6). Figure 17-5 In patients with depression, approximately 80% experience insomnia, whereas only 20% experience hypersomnia. (Modified from Kennedy S, Parikh SV, Shapiro CM: Defeating depression. Thornhill, Ontario, Canada, 1998, Joli Joco Publications.) Figure 17-6 Rates of relapse among depressed patients increase when vegetative symptoms of depression, such as poor sleep, occur during remission. (Modified from Kennedy S, Parikh SV, Shapiro CM: Defeating depression. Thornhill, Ontario, Canada, 1998, Joli Joco Publications.) Sleep architecture abnormalities in patients with depression include disturbances in REM sleep, NREM sleep, and sleep continuity (Table 17-2). Patients with depression experience decreased total sleep time (TST), increased sleep latency (SL), decreased slow-wave sleep (SWS), decreased REM latency, and increased REM density (Fig. 17-7). Several studies have found that significantly shorter REM latency, prolonged first REM sleep period, and increased phasic REM activity were associated with primary depression. The presence of decreased REM latency and increased REM density is 70% sensitive and 90% specific in discriminating individuals with MDE from those without MDE. Although the likelihood of developing depression cannot be predicted based only on these abnormalities, they can predict failure to respond to psychotherapy alone. It is appropriate to screen individuals with these PSG abnormalities for depression and to consider pharmacologic antidepressant treatment.

Sleep and Psychiatric Disease

Overview

Sleep and Depression

Sleep Architecture

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sleep and Psychiatric Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue