Chapter 4 Scoring of abnormal respiration is the component that is most controversial. This section of the atlas provides a number of snapshots (Figs. 4.1–4.30) to illustrate some of the patterns and challenges. Scoring has evolved through time, and most recently, recognizing and mapping dynamic patterns have added new dimensions. New treatment modalities such as adaptive ventilation fundamentally alter waveform characteristics and challenge the current scoring guidelines. FIGURE 4.1 Obstructive sleep apnea. FIGURE 4.2 Complex sleep apnea. FIGURE 4.3 Stabilization effects of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep on chemoreflex-modulated sleep apnea. FIGURE 4.4 Short cycle obstructive apneas in non–rapid eye movement sleep. FIGURE 4.5 Classic periodic breathing/Cheyne-Stokes pattern during continuous positive airway pressure titration. FIGURE 4.6 Bradypnea. FIGURE 4.7 Increased upper airway resistance with consequences. FIGURE 4.8 Ataxic respiration and opiates. FIGURE 4.9 Dynamism in sleep-breathing disorders. FIGURE 4.10 Respiratory events while awake. FIGURE 4.11 Respiratory events while awake. FIGURE 4.12 Stable non–rapid eye movement sleep during adaptive ventilation. FIGURE 4.13 Unstable non–rapid eye movement sleep during adaptive ventilation. FIGURE 4.14 Sleep apnea and parasomnias.

Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Scoring

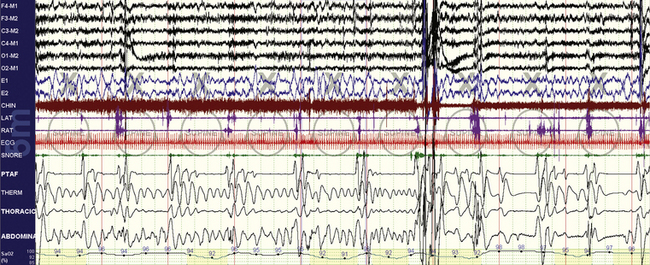

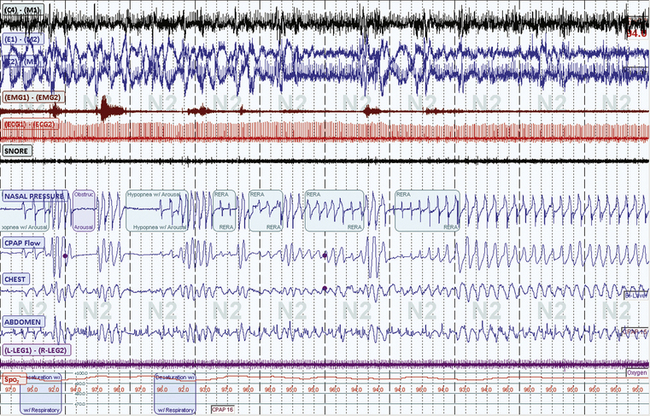

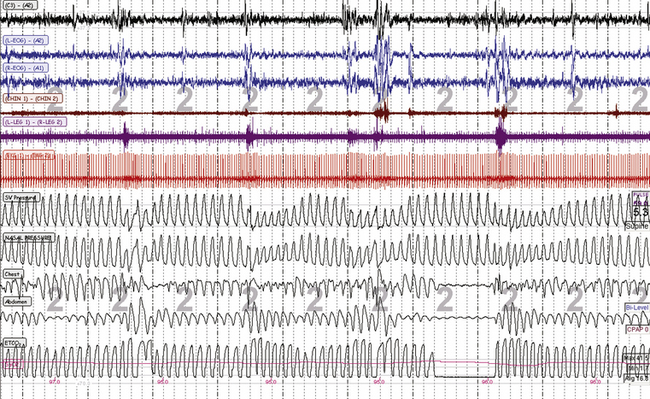

A 10-minute compression is shown in a 47-year-old man. Overt and repetitive obstructive respiratory events with associated oxygen desaturations are seen. Following a larger arousal, postarousal central apneas and respiratory instability are seen. Periodic tibialis motor activations occur associated with respiratory arousals. However, note that many of the events, especially the fourth to seventh events from the left, have a nearly identical timing of 30 seconds. Such timing characteristics (short, metronomical) can reflect strong respiratory chemoreflex modulation of sleep breathing, but by any criteria the events shown here need to be scored as obstructive hypopneas.

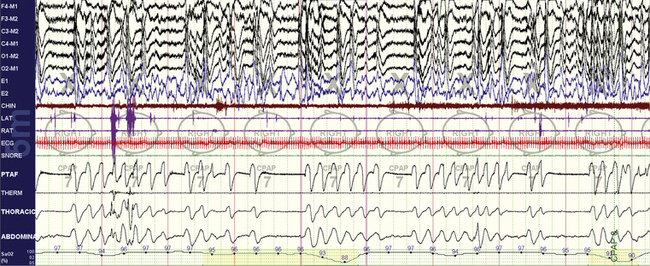

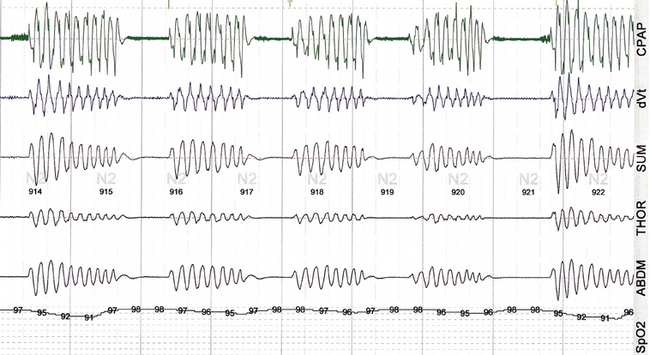

The same subject as in Figure 4.1 while on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). A 10-minute compression is shown. Note the emergence of central apneas at low to moderate CPAP pressures. This pattern persisted through much of non–rapid eye movement sleep. In this snapshot the patient is nonsupine.

The same subject as in Figures 4.1 and 4.2. A 10-minute compression is shown. Note the excellent response to therapy. The body position is supine, and thus positional effects cannot explain the non-REM (NREM) versus REM sleep differences. The NREM-dominant sleep apnea phenotype is readily recognizable and confers a high risk for conversion to the “complex” phenotype.

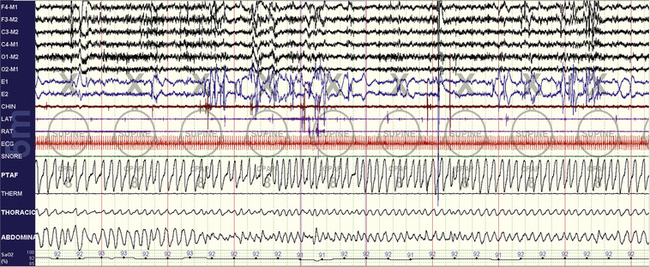

A 10-minute compression is shown in a 32-year-old woman. The events are clearly obstructive yet have few recovery breaths after individual events. The return of oxygen saturation levels to the baseline after arousals suggests that there is no hypoventilation, but end-tidal CO2 monitoring would be required. Note the robust cardiac accelerations and decelerations, but these do not exactly match the timing of arousal/recovery breaths.

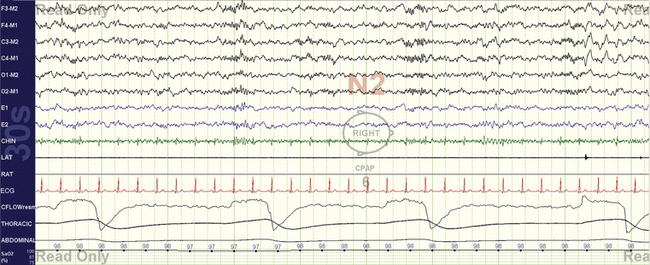

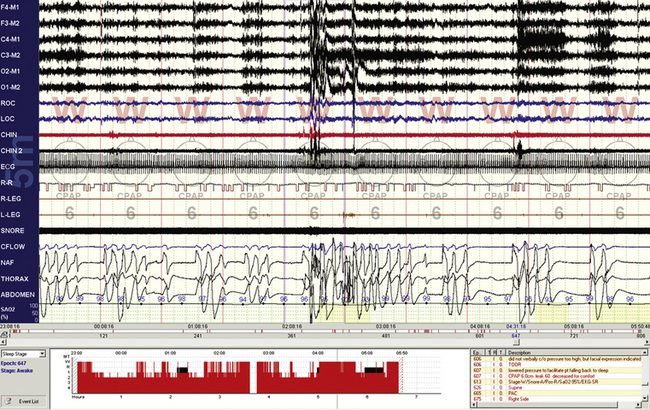

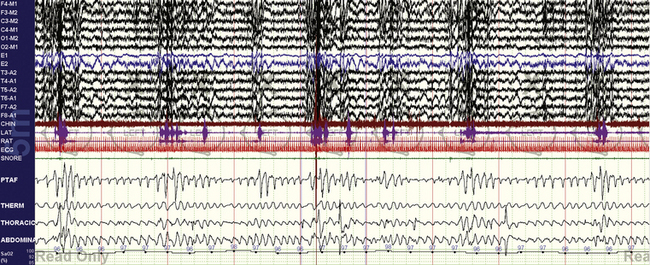

A 59-year-old man with clinical symptoms consistent with sleep apnea, with no other comorbidities. The vertical lines are 30 seconds. The pattern during the diagnostic assessment was identical. This readily recognizable pattern reflects unstable and exaggerated respiratory chemoreflex influences.

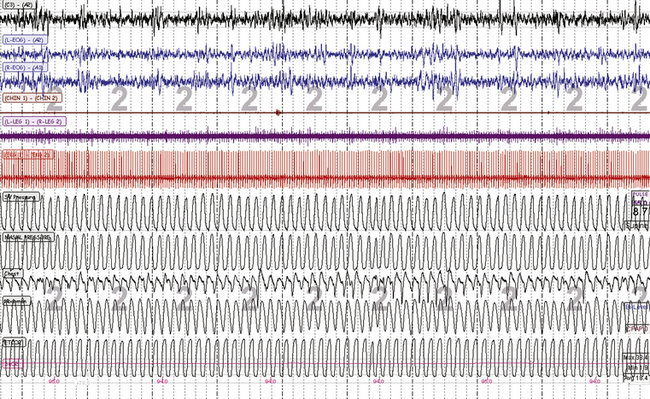

A 30-second epoch snapshot from a 22-year-old with mixed sleep apnea. Respiratory rate is about 8 breaths/min, with prolonged expiration phases that show some variability. The rate while awake was 14 breaths/min, and this pattern was seen during continuous positive airway pressure application. Unexplained sleep bradypnea (which will be designated central apneas if the rate slows down enough) or ataxic respiration in the absence of opiate use in a young individual could raise the possibility of a craniovertebral junction abnormality.

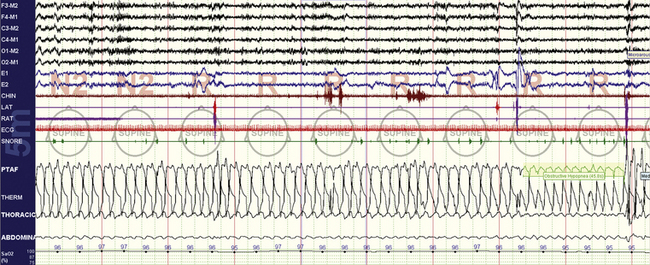

A 26-year-old woman, 10-minute screen compression. The stage is rapid eye movement sleep, with variable degrees of flow limitation (PTAF channel) and arousals characterized by transient chin electromyographic tone increases and recovery breaths. There is no oxygen desaturation.

A 77-year-old woman with spinal stenosis and methadone use. Note the unpredictable variability of the expiratory phase.

A 10-minute screen compression from a 66-year-old male patient with long-standing sleep apnea and a new diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. Repetitive obstructive respiratory events and respiratory instability occur and lead relatively abruptly to a switch to stable non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. Such periods of stability are intrinsic to NREM sleep and in this case occur in stage N2.

A 10-minute compression from a 60-year-old man with stable congestive heart failure. Note that even though the epochs are scored “wake” by conventional criteria, there are repetitive central apneas on continuous positive airway pressure and fluctuating electroencephalographic (EEG) amplitudes and frequency (see EEG channels) associated with these events. The problem reflects limitations of the current epoch-based scoring system. These events may be preventing a proper transition to sleep.

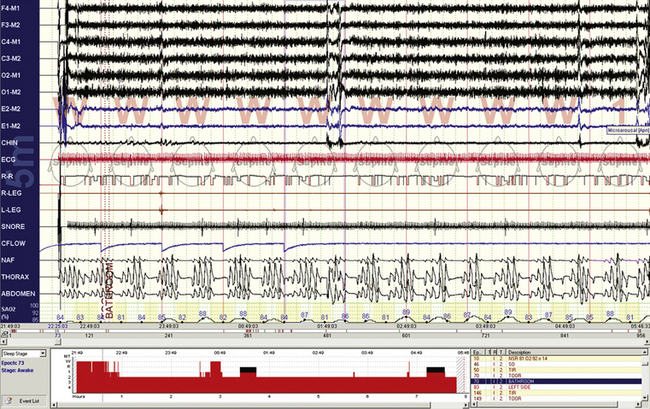

A 10-minute compression from a 56-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Note that even though the epochs are scored “wake” by conventional criteria, there are repetitive central apneas during this diagnostic assessment. The electroencephalogram less clearly shows state transitions than in Figure 4.10, there are no slow eye movements of drowsiness, but the oxygenation fluctuations and respiratory cycling suggest that these events are pathological and related to sleep state or at least the transition to it. Note that the oxygen saturation levels remain low during recovery phases, likely because of reduced lung functional reserve.

A 10-minute screen compression during titration of adaptive ventilation and dead space use in a 58-year-old male patient with congestive heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Note overall stability of sleep and respiration. The respiratory signals from top are servo ventilation (SV) pressure (pressure output from the ResMed VPAP Adapt SV), nasal pressure (mask pressure), chest and abdominal effort, and mainstream end-tidal CO2 (maximum is 38.4 mm Hg).

A 10-minute screen compression during titration of adaptive ventilation and dead space in the same patient as in Figure 4.12. The respiratory signals from top are spontaneous ventilation (SV) pressure (pressure output from the ResMed VPAP Adapt SV), nasal pressure (mask pressure), chest and abdominal effort, and mainstream end-tidal CO2 (maximum is 38.4 mm Hg). Note the “pressure cycling” profile of the servo ventilation (SV) pressure that signifies adaptive responses to ongoing periodic breathing. Conventional scoring can be challenging during adaptive ventilation: effort signals reflect machine plus patient, and the flow signals can be continuously undulating—with a reduction in pressure during recovery breaths, exactly the opposite relative to continuous positive airway pressure titration. However, the ongoing arousals suggest that these events need to be scored as hypopneas with arousals.

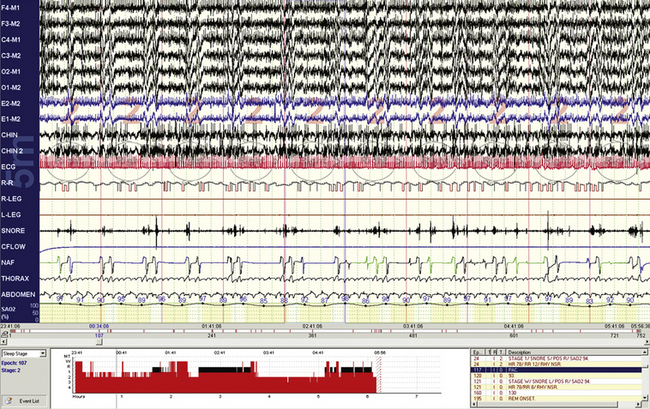

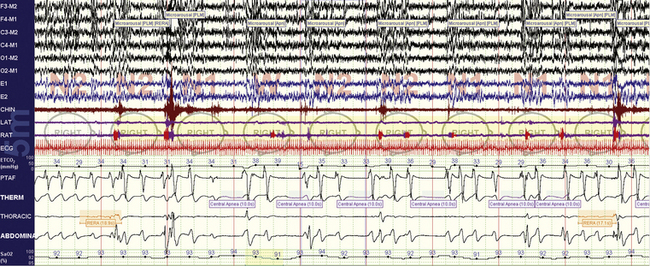

A 25-year-old man presents with what could be nocturnal seizures or non–rapid eye movement (NREM) parasomnias. There is no snoring or daytime sleepiness. The diagnostic polysomnogram shows repetitive nonhypoxic respiratory events, no clear epileptiform activity, and vigorous arousals. Sleep apnea may be asymptomatic (no sleepiness) in those with NREM parasomnias, whereas treatment of sleep apnea can stop clinical expression of NREM parasomnias.

Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Scoring

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree