Sleep Disorders

Thomas F. Anders

Introduction

Our understanding of clinical sleep disorders has advanced significantly since the 1950s, when polysomnographic (PSG) recordings first described the rapid eye movement (REM) and nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep states. Aserinsky and Kleitman (1) first described the electrophysiological differences between the two states of sleep. Today, standards of practice, official nosologies, and certification processes are all in place. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine certifies clinical laboratories and the technicians who record sleep, and the American Boards of Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Psychiatry/Neurology have collectively agreed to certify board-eligible clinicians in a new subspecialty, sleep disorders

medicine. A pediatric section of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies, the national professional organization of sleep specialists, held its first organizing and scientific meeting in 2005 and is planning a second meeting in 2006. Unfortunately, child and adolescent psychiatrists continue to be underrepresented in all of these groups.

medicine. A pediatric section of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies, the national professional organization of sleep specialists, held its first organizing and scientific meeting in 2005 and is planning a second meeting in 2006. Unfortunately, child and adolescent psychiatrists continue to be underrepresented in all of these groups.

How are sleep disorders defined and diagnosed? A number of psychophysiological systems are routinely recorded in a sleep laboratory: peripheral muscle tone (electromyogram, EMG) from submental muscles, horizontal and vertical eye movements (electrooculogram, EOG) from electrodes placed peri-orbitally, the electroencephalogram (EEG) from an array of scalp electrodes, and cardiac, respiratory, and peripheral motor activity from thermistors placed around the chest, airway, and limbs. Eye movement, muscle tone, and EEG patterns are the primary parameters used to score REM and NREM sleep states. Patterns of obstructed breathing, heart rate irregularity, and episodic behaviors, including limb movements, are associated features useful in diagnosing specific sleep disorders.

PSG studies are largely confined to nighttime recordings in a sleep laboratory. However, sleeping in an unfamiliar sleep laboratory disrupts normal sleep architecture and often requires recording over several nights to eliminate the “first night” stress effect. The need for multiple nights of recording has made sleep research with young subjects difficult as both children, wired with an array of electrodes and thermistors in an unfamiliar sleep laboratory, and their parents are reluctant to sleep away from home for even one night. Ambulatory polysomnography, actigraphy, and time-lapse video recording have greatly expanded the scope of sleep evaluations by providing opportunities for home recording and for 24-hour recording.

Neurophysiology of Sleep States

The EEG pattern during REM sleep is low voltage, fast, resembling the EEG of wakefulness; the EMG pattern is inhibited and the EOG is characterized by bursts of vertical and horizontal saccadic eye movements. Heart and respiratory rates are rapid and irregular. Neuronal firing, neurotransmitter release and uptake, and metabolic rates also resemble patterns of waking. Mental activity during REM sleep is present and is reported as dreams. Thus, during REM sleep, an individual appears asleep, but for the most part the central nervous system is highly activated. In infants, REM sleep has been called active sleep.

In contrast to the psychophysiological activation of REM sleep, NREM sleep is characterized by more basal, organized patterns of physiological inhibition. Both respiratory and heart rates are slowed and more regular. The EEG is synchronized with specific slower frequency wave forms. In infants NREM sleep is also called quiet sleep. The EEG of stage 1 NREM sleep resembles the tracing of REM sleep; however, respiratory and heart rate patterns are regular, and saccadic eye movements are absent. The EEG of stage 2 NREM sleep contains K complexes and sleep spindles. Stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep have varying amounts of slow, high-voltage synchronized delta waves. In newborns, only two sleep states— REM sleep and NREM sleep— can be distinguished. By 6 months of age, the specific EEG waveforms that are used to subclassify the four stages of NREM sleep have emerged.

Development of Sleep-Wake State Organization

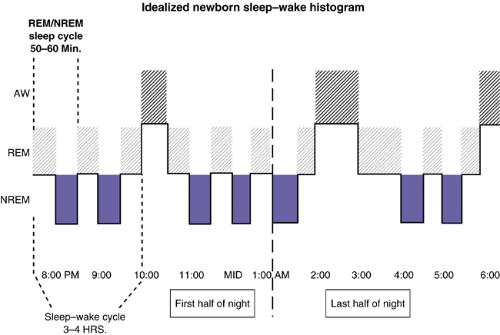

The characteristics of the electrophysiologic patterns and the proportions of sleep-wake states change with development. Proportionally in adults, REM sleep occupies about 20% and NREM sleep about 80% of total sleep time each night. Stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep account for approximately 20% of all NREM sleep. In newborns, REM sleep occupies 50% of total sleep time (2). REM and NREM sleep states alternate with each other in sleep cycles that recur periodically through the sleep period. In adults, the REM-NREM sleep cycle length averages 90 minutes; in infants the cycle length is approximately 50 minutes. Adult sleep organization is achieved by adolescence (Table 5.9.1).

TABLE 5.9.1 SLEEP-WAKE STATE CHANGES WITH AGE | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

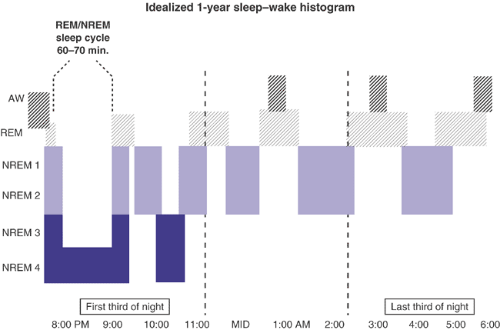

In adults, sleep typically begins with NREM stage 4 sleep, and the first third of the sleep period has most of the total night’s stage 4 NREM sleep. That is, although REM-NREM cycles recur at 90-minute intervals throughout the night, the percentage of stage 4 NREM sleep in a single cycle is greater during the early part of the night than later in the night. The proportion of REM sleep in a single sleep cycle is greater during the latter part of the night.

In infants, sleep begins with an initial REM period, and sleep cycles throughout the night include as much REM sleep as NREM sleep. No early- and late-night differences in REM–NREM proportions are found. The shift in the temporal organization of states during the course of a night’s sleep, which begins in the first month of life, reflects the maturation of internal central nervous system timing mechanisms. That is, biological clocks mature to regulate both the ultradian and circadian control mechanisms to achieve sleep-wake state consolidation. These changes are depicted schematically in Figures 5.9.1 and 5.9.2.

An understanding of these developmental changes is important for understanding the presentation of specific sleep disorders that affect infants, children, and adolescents.

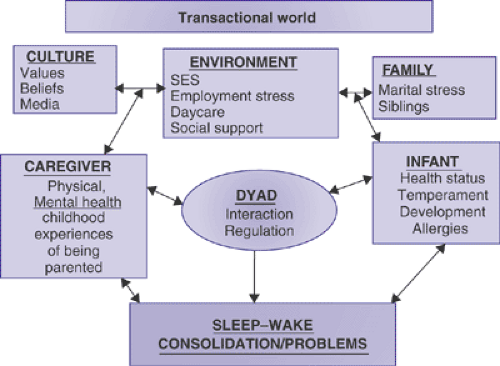

From Dyadic Regulation to Self-Regulation: A Transactional Model

During early development, transitions between sleep and waking at bedtime and during the middle of the night offer multiple opportunities for parent–infant interaction (3). Sensitive responses during these interactions facilitate the development of self-regulation. An assessment of sleep disturbances in the infant, toddler, and preschool child, therefore, necessarily involves assessment of the parent–child interactions and the psychosocial factors that impact that relationship. Figure 5.9.3 schematically depicts a transactional model useful in the evaluation of sleep disorders in young children (4).

Proximal influences on the relationship include the primary caregiver’s current state of physical and psychological well being, the primary caregiver’s own childhood experiences of being parented, including their experiences around sleep, current social support networks, the family’s economic and household condition, and the infant’s temperament and physical health. More distal factors in the transactional

model include the broader cultural context and belief systems of the family and more indirect environmental influences. Stressors, such as infant physical illness or maternal depression, serve as proximate factors that directly impact parent–child interaction. At bedtime and during the night, if parental sensitivity and consistency are affected, the regulation of sleep may become disrupted. In turn, when the infant’s sleep becomes disorganized, the entire family is impacted, which in turn affects infant sleep-wake regulation.

model include the broader cultural context and belief systems of the family and more indirect environmental influences. Stressors, such as infant physical illness or maternal depression, serve as proximate factors that directly impact parent–child interaction. At bedtime and during the night, if parental sensitivity and consistency are affected, the regulation of sleep may become disrupted. In turn, when the infant’s sleep becomes disorganized, the entire family is impacted, which in turn affects infant sleep-wake regulation.

FIGURE 5.9.1. Note the regular distribution (∼50:50) between REM and NREM sleeps throughout the sleep cycle and the initial REM sleep period at sleep onset. |

In early childhood, a sleep problem may be specific to a particular relationship or setting. A child may nap at the daycare center but not at home (or vice-versa), or a child may fall asleep more easily when the babysitter puts the infant to bed

than when the parent does (or vice-versa). Sometimes, infants and young children’s sleep problems present differentially with mothers and fathers.

than when the parent does (or vice-versa). Sometimes, infants and young children’s sleep problems present differentially with mothers and fathers.

Classification of Sleep Disorders in Childhood

Several nosologies for classifying pediatric sleep disorders are currently available, although none adequately present criteria for the night waking and sleep resistance problems that are such prevalent concerns of parents of young children. They are The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2nd Edition (ICSD-DCM2) (5), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (6) and Diagnostic Classification: Zero to Three, Revised (DC 0-3R) (7). Table 5.9.2 compares their principal similarities and differences.

All three nosologies define major categories of disordered sleep: 1) dysomnias; 2) parasomnias; and 3) sleep disorders associated with medical/psychiatric conditions. Each of the systems then subclassifies the major categories slightly differently. Dysomnias are defined as disruptions of sleep-wake state organization, i.e., the disruption of the REM-NREM pattern. Parasomnias are defined as intrusions of events upon a normally organized sleep-wake process.

ICSD-DCM2 lumps together the disorders of night waking and sleep resistance, so common in early childhood, as behavioral sleep disorders. Cut points are not specified, especially as they pertain to differentiating disorder from typical age-appropriate behaviors. Similarly, the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for dysomnias in young children often are not easily met, especially for the primary insomnias and hypersomnias.

New quantitative and more developmentally appropriate research diagnostic criteria (RDC) for disorders of initiating and/or maintaining sleep (dysomnias) for younger children have been proposed (8) (Tables 5.9.3 and 5.9.4). Because they do not meet full adult criteria of DSM-IV-TR for functional impairment, the disorders are referred to as “protodysomnias.” Perturbations refer to age-appropriate temporary disruptions of sleep patterns, such as the behavioral sleep response related to an acute respiratory infection. Perturbations are time limited and self correcting. Disturbances suggest potentially more significant risk conditions that warrant monitoring and, perhaps, parent guidance. Disorders are persistent and severe and require treatment. Further research with large, ethnically diverse populations, focused on age-related prevalence, natural course and efficacy of guidance and treatment programs, is necessary before these criteria can be officially adopted.

DC 0-3R, like DSM-IV-TR, is a multiaxial nosology of mental disorders developed specifically for use in infancy and early childhood. DC 0-3R provides several opportunities to classify sleep problems, either as a primary entity or as a symptom of another Axis 1 disorder such as traumatic stress disorder, adjustment disorder, regulatory disorder, anxiety disorder or mood disorder. For the primary sleep disorder category, DC 0-3R has adopted the research diagnostic criteria for sleep onset and night waking protodysomnias described next.

A Developmental Approach to Diagnosis

Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers

Night Waking and Sleep Onset Protodysomnias

“My infant is not sleeping through the night” is one of the most common concerns of parents at the time of well baby

visits. Some parents expect their infants to sleep through the night shortly after birth. Others complain that their infant “resists falling asleep” and must be rocked or nursed to sleep for prolonged periods. Occasionally, health professionals prescribe hypnotics or antihistamines for 6- to 12-month-old infants with these problems, or they may counsel parents to let their babies cry.

visits. Some parents expect their infants to sleep through the night shortly after birth. Others complain that their infant “resists falling asleep” and must be rocked or nursed to sleep for prolonged periods. Occasionally, health professionals prescribe hypnotics or antihistamines for 6- to 12-month-old infants with these problems, or they may counsel parents to let their babies cry.

TABLE 5.9.2 SLEEP DISORDERS NOSOLOGIES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 5.9.3 NIGHT-WAKING DYSOMNIA IN TODDLERS AND PRESCHOOLERS (OCCURS AFTER INFANT HAS BEEN ASLEEP FOR >10 MINUTES) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During the second year of life, toddlers commonly resist bedtime and separating from their parents. Infants with significant problems have severe and intractable battles at bedtime associated with frequent and prolonged bouts of night waking that begin shortly after sleep onset and persist until morning rise time. These more serious disorders become a major source of family tension and are usually associated with significant parental conflict about managing the infant’s sleep.

Preschoolers, especially if there are older siblings in the family, enjoy participating in the family’s evening activities. Since many families have irregular schedules, time with parents may be a precious commodity that the child wishes to prolong. Young children fervently deny being tired when asked. When daytime experiences for preschoolers are too exciting or overstimulating, calming down at bedtime may be difficult. The role of television in overstimulation and fear arousal has also been posited. Whatever the causes, the preschool child may protest vigorously, attempting to delay bedtime. Examples of protestation include requesting bedtime stories to be repeated, returning for more good-night hugs and kisses, asking for another glass of water or snack, and pleading for “five more minutes” until bedtime. A child may also insist on falling asleep in the parents’ bed or while lying next to and holding the parents.

TABLE 5.9.4 SLEEP ONSET DYSOMNIA IN TODDLERS AND PRESCHOOLERS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|