Chapter 12

Sleep Dysfunction and Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Miscellaneous Neurological Disorders

Control of Breathing in Sleep and Wakefulness

The central respiratory neurons controlling respiration during sleep and wakefulness (metabolic or automatic system) are located in the medulla in the region of the nucleus tractus solitarius, nucleus ambiguus, and nucleus retroambigualis. The voluntary respiratory system is located in the cerebral cortex and projects partly to the metabolic system in the medulla but mostly descends to the upper cervical spinal cord where the metabolic and the voluntary systems are integrated. Therefore these anatomical locations make these structures controlling sleep-wakefulness and breathing highly vulnerable to the neurological lesions affecting the cortical and subcortical structures. Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) therefore occurs in many central neurological disorders, as well as in peripheral neurological disorders such as polyneuropathies, neuromuscular junction disorders, and muscle diseases by causing weakness of the respiratory muscles. SDB has been described in many neurodegenerative disorders, “strokes,” other structural affections of the brainstem and upper cervical spinal cord, as well as in many neuromuscular diseases.

Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Other Sleep Dysfunction in Neurological Diseases

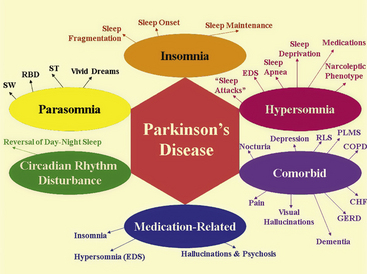

In this section of the atlas we are illustrating a few selected neurological disorders causing a variety of sleep dysfunction and SDB. SDB has been estimated to be present in 33% to 53% of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (Fig. 12.1). Whether the prevalence of sleep apnea in AD patients is related to the advancing age of the patient and whether sleep apnea increases the severity of illness or more rapid progression of the disease remains to be determined. SDB causes cognitive impairment, and therefore it is most probable that the presence of SDB will adversely affect these demented patients, although there is some controversy about this. SDB (obstructive, central, and mixed apneas), as well as laryngeal stridor, may be more common in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients than in age-matched controls. Those PD patients with autonomic dysfunction show increased incidence of SDB (Fig.12.2). Figure 12.3 schematically shows the spectrum of sleep dysfunction in PD. Multiple system atrophy (MSA), another degenerative disease of the autonomic and somatic neurons, initially presents with progressive autonomic failure followed by progressive somatic neurological manifestations affecting multiple systems. The term Shy-Drager syndrome is used to describe the condition in which autonomic failure is the predominant feature. The term striatonigral degeneration is used to describe the condition in which the predominant feature is parkinsonism, whereas sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA) is used when cerebellar features are the predominant manifestations. A variety of sleep-related respiratory disturbances may occur, which include obstructive, central, and mixed apneas and hypopneas; dysrhythmic breathing; Cheyne-Stokes respiration; and nocturnal inspiratory stridor (Fig. 12.4). In addition to the sporadic OPCA, patients with dominant OPCA may also have central, upper airway obstructive, or mixed apneas, but these are less frequent and less intense in this condition than in MSA.

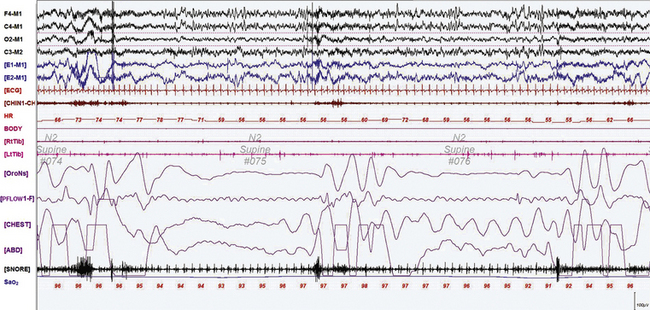

FIGURE 12.1 A case of Alzheimer’s dementia and sleep-disordered breathing.

Polysomnographic recording in a 75-year-old man in an advanced stage of Alzheimer’s disease with profound dementia, excessive daytime sleepiness, and severe nocturnal sleep disturbance. He had severe obstructive sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index 68/hr in general, O2 saturation nadir of 77%) with several obstructive, central, and mixed apneas. This 90-second epoch shows first a mixed and then an obstructive apnea. Top four channels, Electroencephalographic recording with electrodes placed according to the 10-20 international electrode placement system; E1-M1 and E2-M1, electro-oculogram channels; ECG, electrocardiogram; CHIN1-CHIN2, mentalis electromyogram; HR, heart rate; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior electromyogram; OroNs, oronasal airflow; PFLOW; nasal pressure transducer recording; CHEST and ABD, effort belts; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry. Also included is a snore channel.

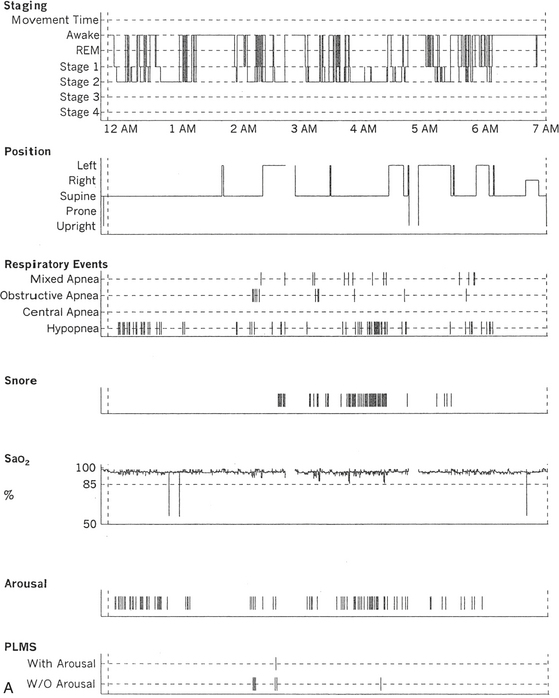

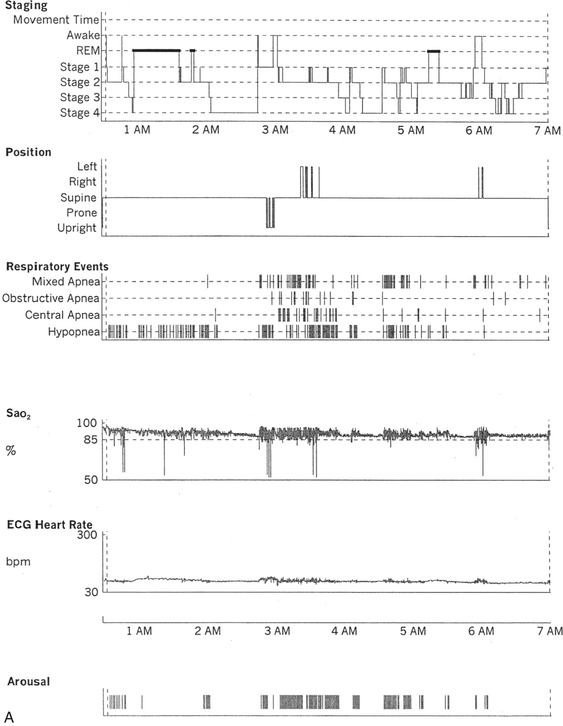

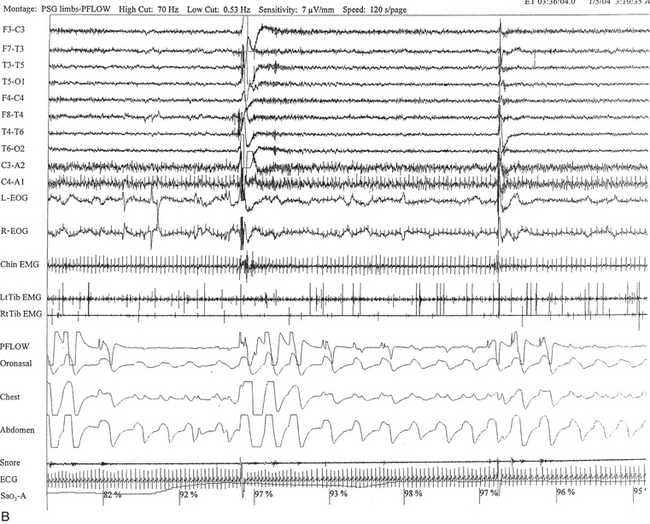

FIGURE 12.2 A case of Parkinson’s disease and sleep-disordered breathing.

A 67-year-old man with history of loud snoring for several years, mild daytime sleepiness, and light-headedness on standing up in the last 2 to 3 months. His past medical history is significant for Parkinson’s disease diagnosed about 2 years ago (currently stage II Hoehn-Yahr scale) and hypertension. A prior sleep study performed approximately 3 years ago had diagnosed severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. He tried continuous positive airway pressure treatment unsuccessfully and has been using a dental appliance every night for the last 2 years, which has somewhat decreased his daytime sleepiness. A, Hypnogram shows sleep architectural changes with frequent stage shifts and awakenings resulting in a decreased sleep efficiency of 54%. Slow-wave sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep are conspicuously lacking. Frequent respiratory events, particularly hypopneas, are recorded throughout the night associated with mild O2 desaturation and arousals. The apnea-hypopnea index is moderately increased at 25/hr. The multiple sleep latency test shows a mean sleep latency of 1.75 minutes consistent with pathological sleepiness. Several sleep complaints, commonly sleep maintenance insomnia, hypersomnia, and parasomnias, particularly REM behavior disorder, are reported in Parkinson’s disease patients. Some patients may also have obstructive and central sleep apnea, but adequate studies have not been undertaken to see if apneas are part of the intrinsic disease process or related to aging. B, A 60-second excerpt from an overnight polysomnogram showing an obstructive sleep apnea in stage II non-REM sleep associated with mild O2 desaturation and followed by an arousal. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin EMG, electromyography of chin; LtTib, RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior electromyogram; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography; Sao2, oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; PLMS, periodic limb movements in sleep.

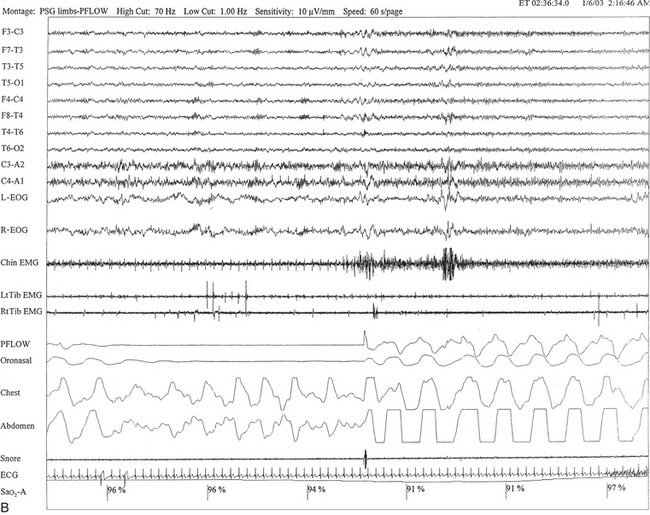

FIGURE 12.3 The spectrum of sleep dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease.

CHF, Congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PLMS, periodic limb movements in sleep; RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; RLS, restless legs syndrome; ST, sleep terror; SW, sleep walking.

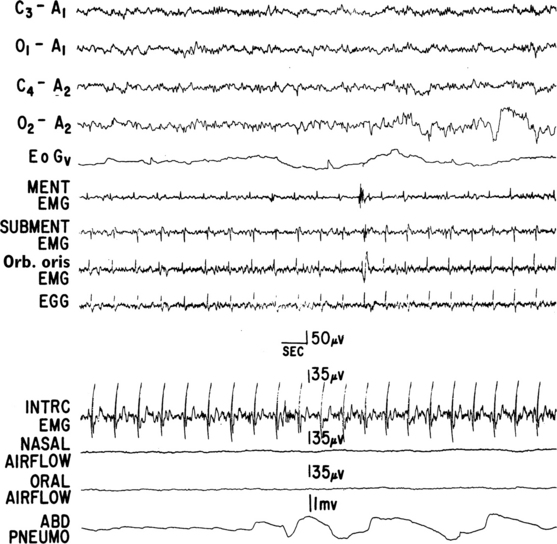

FIGURE 12.4 A case of multiple systems atrophy (Shy-Drager syndrome) and sleep-disordered breathing.

Polysomnogram (PSG) recording in a 58-year-old patient with olivopontocerebellar atrophy presenting with ataxic gait, scanning dysarthria, nystagmus, marked finger-nose and heal-knee incoordination, and bilateral extensor plantar responses. Laboratory test results showed evidence of dysautonomia. PSG shows a portion of an episode of mixed apnea during stage II non-REM sleep. Top four channels, Electroencephalograms; EOGv, vertical electro-oculogram; MENT, mentalis; EMG, electromyography; SUBMENT, submentalis; Orb. oris, orbicularis oris; EGG, electroglossogram; INTRC, intercostal muscles; ABD PNEUMO, abdominal pneumogram. (From Chokroverty S, Sachdeo R, Masdeu J. Autonomic dysfunction and sleep apnea in olivopontocerebellar degeneration. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:509, with permission.)

In several multiple sclerosis patients, SDB abnormalities have been described, including predominant central sleep apnea and ataxic or Biot’s breathing (Fig. 12.5). SDB in such a condition may result from a demyelinating plaque involving the hypnogenic and respiratory neurons in the brainstem. In Arnold-Chiari malformation, particularly in type I malformation, several patients have been described with central and upper airway obstructive sleep apneas, as well as profound sleep hypoventilation (Fig. 12.6).

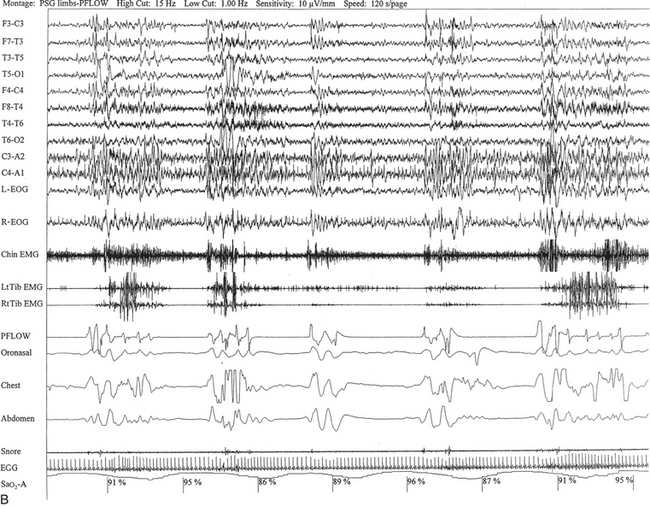

FIGURE 12.5 A case of multiple sclerosis and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

A 51-year-old woman with history of multiple sclerosis diagnosed 7 years ago. Her sleep difficulties started approximately 3 years ago and are described as frequent night awakenings, sleepwalking, and brief episodes consisting of sudden sleepiness or impairment of consciousness resulting in falls and multiple fractures but never accompanied by jerky movements of the limbs, tongue biting, or incontinence, with spontaneous recovery in 5 to 10 minutes without residual confusion. These episodes occur during early morning hours, as well as during the day. Her neurological examination is significant for the presence of decreased visual acuity and impaired saccades bilaterally, horizontal nystagmus on looking to the left, intention tremor (left more than right) on finger-to-nose testing, mild ataxia in the lower extremities on heel-to-shin testing, tandem ataxia, and impaired joint and position sense in the toes bilaterally. She was clinically evaluated with a differential diagnosis of SDB related to multiple sclerosis, narcolepsy-cataplexy secondary to multiple sclerosis, and sleepwalking. Unusual nocturnal seizures remained unlikely given the clinical features, the several negative electroencephalograms (EEGs), and the negative long-term epilepsy monitoring. A, Hypnogram significant for rapid eye movement (REM) sleep distribution abnormality (longest REM in the early part of the night); frequent obstructive, mixed, and central apneas and hypopneas both during non-REM and REM sleep; mild-moderate O2 desaturation; and frequent arousals. Sleep-related respiratory dysrhythmias caused by brainstem involvement are a common finding in multiple sclerosis patients. B, A 120-second excerpt from overnight polysomnographic recording showing repeated central apneas with O2 desaturation. Note that some of these events have the characteristics of Biot’s breathing (a variant of ataxic breathing). An increase in muscle tone is noted on chin and tibialis anterior electromyogram (EMG) channels following some central events. Top 10 channels, EEG; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin EMG, electromyography of chin; LtTib, RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior electromyography; PFLOW, peak flow; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography; Sao2, oxygen saturation by finger oximetry.

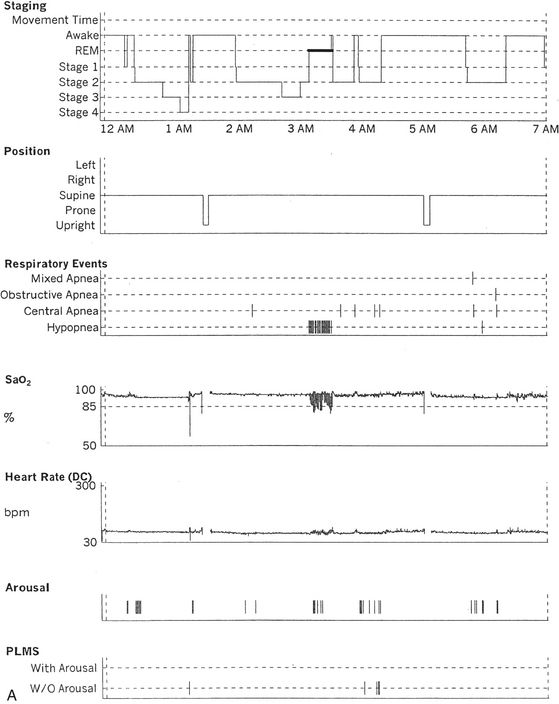

FIGURE 12.6 A case of Arnold-Chiari malformation and sleep-disordered breathing.

A 52-year-old man with history of tiredness and excessive daytime sleepiness for many years but no cataplexy, sleep paralysis, or hypnagogic hallucinations. At the age of 27 years, he complained of gait problems, and magnetic resonance imaging examination revealed Arnold-Chiari malformation type I. His neurological examination is significant for the presence of a coarse horizontal nystagmus, minimal right lower facial weakness, minimal right wrist extensor muscle weakness, minimal to mild ataxia in upper and lower extremities on coordination testing, and presence of ataxia on tandem gait. A, Hypnogram shows a few periods of apneas and hypopneas accompanied by mild-moderate oxygen desaturation and arousals limited exclusively to a single rapid eye movement (REM) sleep period recorded during the night. A supine posture is maintained throughout the polysomnographic recording. These findings are suggestive of REM sleep–related hypoventilation. Central sleep apnea, obstructive sleep apnea, and hypoventilation have all been described in patients with Arnold-Chiari malformation, likely from brainstem involvement. B, A 120-second excerpt from REM sleep showing one obstructive apnea followed by two sequential hypopneas; O2 desaturation of 82%, likely from a prior respiratory event, is recorded at the onset of the epoch. The first two events are followed by an arousal response, and the epoch does not include the complete recovery phase of the third event. Phasic eye movements of REM sleep are noted on the electro-oculogram channels in the early part of the epoch. Phasic muscle twitches of REM sleep are noted on both tibialis anterior electromyogram (EMG) channels. Chin EMG channel shows electrocardiography artifact. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin EMG, electromyography of chin; LtTib, RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior electromyography; PFLOW, peak flow; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography; Sao2, oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; PLMS, periodic limb movements in sleep.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree