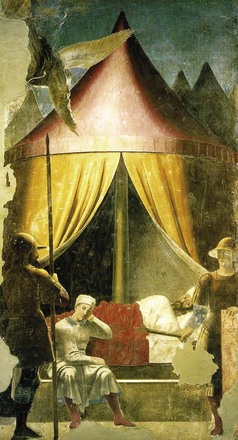

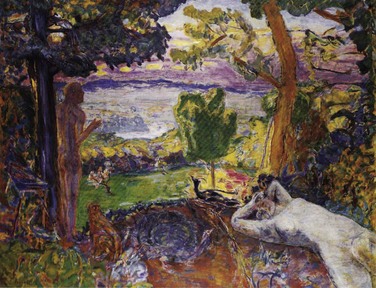

Chapter 1 The scientist explores the functions, mechanisms and pathologies of sleep (Fig. 1-1). Visual artists, on the other hand, are not concerned with these matters; instead, when representing sleep, a number of themes repeatedly emerge. They have intense fascination with mythology, dreams, religious themes, the parallel between sleep and death, reward, abandonment of conscious control, healing, a depiction of innocence and serenity, and the erotic. An example of this is Sandro Botticelli’s Mars and Venus (Fig. 1-2). In this painting, the fully clothed Venus sits at the left, upright and alert, whereas the sleeping Mars on the right lies languidly, incapacitated, exposed, and vulnerable. Venus appears to be in control while Mars is reduced to being a plaything for the baby satyrs. Thus, this painting likens the state of sleep to weakness. It is a powerful force that can overtake the god of war. Sleep is undesirable because it is capable of lowering the defenses of someone as formidable as the god of war. The god of war becomes subject to humiliation. Furthermore, he has become prey to the outside world. This power of sleep is often not appreciated by patients, even those who suffer from sleep disorders, who may need to be reminded, for example, that sleep deprivation is used as a technique of torture. In other words, sleep is so highly necessary that “take those sleeping pills” may be the simplistic mantra. Lorenzo Lotto’s Sleeping Apollo (Fig. 1-3) portrays sleep in a manner similar to that of Botticelli’s Mars and Venus. Once again, the sexes are divided; the naked female Muses are on the left and the slumbering Apollo sits on the right. Fame, who flies above Apollo, is ready to desert him and join the other Muses. The Muses have taken advantage of the sleeping Apollo to abandon their clothes and arts to frolic about. Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (Fig. 1-4), instead of two figures, has one, the female figure, who is sleeping. As in the other two paintings, Venus lies in a pastoral setting; but unlike in Mars and Venus, she is alone, and she is the one who is sleeping and nude. The curves of her body emulate the undulating hills. She has her left hand covering her genitals. This is an extremely erotic picture. Instead of classical mythology, many artists have turned to the Bible in their representations of sleep. In his oil painting Earthly Paradise (Fig. 1-5), Pierre Bonnard depicts a slumbering Eve and an alert Adam. Bonnard uses the same pictorial language in his rendering of Eve: the exposed armpit and her rounded form alluding to nature. Her rendering and sleeping posture make her look thanatotic. Figure 1-5 Pierre Bonnard, Earthly Paradise, 1916–1920. The Art Institute of Chicago. (Used with permission. Copyright 2008 Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York/ADAGP, Paris.) In works such as Piero della Francesca’s Dream of Constantine (Fig. 1-6), sleep is depicted as the state in which the divine communicates with humans. This is a common occurrence in mythology and religious stories. Well-known instances are the Bible’s Jacob and his dream of the ladder that reached heaven, as well as the Egyptian Pharaoh’s prophetic dreams that would be interpreted by Joseph. Whatever the story, it is necessary that the protagonist enter the state of sleep in order to hear God speak to him. In this early Renaissance painting, Constantine is shown reposed in a tent and is flanked by his sentinels. There is—or what appears to be—an angel swooping from the upper left corner as if to deliver a divine message from God. This image depicts the moment, Laurie Schneider Adams tells us, when Constantine’s dream “revealed the power of the Cross, and led to his legal sanction of Christianity.” As opposed to Botticelli’s Mars and Venus and Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, Constantine is neither emasculated nor empowered with sexual prowess. Sleep is depicted as a state wherein only the divine becomes revealed and the sleeper can realize higher states of consciousness. This is further exemplified by the contrast between Constantine and his guards. The leader is composed and peaceful in his rest as though receptive to a divine message. (This may be thought of as a foreshadowing of current research that links sleep in a critical way with the consolidation of memory.) The soldiers, on the other hand, appear languid and unaware of the angel that is delivering the message. The artist uses both this event and sleep as a way to demonstrate the former and to explore the latter. It is interesting to note that the title and content of the painting force the viewer to ask whether he or she is witnessing an event that is occurring in reality, or are we privy to the actual dream of Constantine? Are we the awake sleepers who are also in Constantine’s higher state and are witnessing the delivery of this divine message?

Sleep in Art and Literature

Mythology

Religion

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree