Fig. 11.1

Descartes’ (1632) model of the brain awake showing tense fibers and strong spirits. Diagram M. The spirits leave gland h ( pineal), having dilated a ( ventricles) and having partly opened all pores (a), and flow to b ( fibrous mesh of the brain substance) and then to c ( membrane enveloping this mesh) and finally into d ( origins of the cranial nerves) [3]

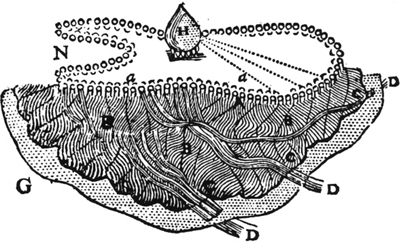

Fig. 11.2

Descartes’ (1632) model of the brain asleep, showing lax fibers, and spirits reduced and gradually become replenished. Diagram n. The spirits have left gland h ( pineal), the ventricles are mainly reduced and the pores (a) become shut down, and flow to b ( fibrous mesh of the brain substance) and c ( membrane enveloping this mesh) is reduced and the nerves d ( origins of the cranial nerves) become relaxed. Parts of the ventricles are still dilated ( dotted lines) that allows for dreaming during sleep [3]

The beginning of the seventeenth century was the time of William Shakespeare (1564–1616) who made many references to sleep in his writings. Insomnia was a particular topic, as was sleepwalking [4].

…the innocent sleep,

Sleep that knits up the ravell’d sleave of care,

…Chief nourisher of life’s feast.

Shakespeare: Macbeth, Act II [4].

The chemical principles of Paracelsus were advanced in the seventeenth century, and medicines, including the use of mercurials, began to take over from treatments such as purging and bloodletting. Illness was then considered to be something that attacked the body in a distinct manner, and the galenic and earlier concepts that disease was a derangement of humors, the essential elements of the body, were starting to fade. The concept of disease was “exogenous” compared to “endogenous” of previous times, so that therapy was aimed at an external cause.

Atomism involved the theory that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void. Atomism, which had been proposed by Democritus, Leucippus, and Epicurus, several centuries before the time of Christ, underwent a revival in the seventeenth century, and was supported by the findings of Jan Baptista van Helmont (1577–1644), who coined the term “gas” and recognized that air was composed of a variety of gases [5]. Van Helmont regarded disease as an internal reaction to some provocation or stimulus from the environment.

Robert Boyle (1627–1691) demonstrated the importance of air for life, and the effect of gases under pressure, which led to the discovery that the reddening of venous blood occurred because of exposure of blood to gases in the air. However, the major discovery of the seventeenth century was that of William Harvey, who was the first to demonstrate that blood was pumped around the body by the heart . It was against this background that the great neurologists, Thomas Willis (1621–1675) and Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689), developed the principles and practice of clinical neurology.

Willis contributed to the knowledge of various disorders in sleep, including restless legs syndrome , nightmares, and insomnia . He recognized that a component contained in coffee could prevent sleep and that sleep was not a disease but primarily a symptom of underlying causes. His book The Practice of Physick devoted four chapters to disorders producing sleepiness and insomnia [6]. As with Descartes , he considered that the animal spirits contained within the body undergo rest during sleep. However, he believed that the animal spirits residing in the cerebellum became active during sleep to maintain a control over physiology. He believed that some of the “animal spirits” became intermittently unrestrained, leading to the development of dreams. He also described restless legs syndrome, which he considered an escape of the animal humors into the nerves supplying the limbs:

when being abed, they betake themselves to sleep, presently in the arms and legs, leapings and contractions of the tendons, and so great a restlessness and tossings of their members ensue, that the diseased are no more able to sleep, than if they were in a place of the greatest torture.

(Willis, 1684) [6]

Willis discovered that laudanum, a solution of powdered opium, was effective in treating the restless legs syndrome . Willis also wrote extensively about sleepiness and lethargy . One form of sleepiness that was often reported in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and discussed by Willis was “continual sleepiness”:

…the affected as to other things are well enough, they eat and drink well, they walk about,…they now and then nod, and unless they are stirred by others, they are presently overwhelmed with sleep: and after this manner they sleep almost continual sleep, not only for some days or months, but for many years… Thomas Willis 1684 [6]

In 1705, William Oliver described a patient in detail in an article entitled “An account of an extraordinary sleepy person,” who was 25 years of age when he developed sleepiness which initially lasted a month, where he could only arouse to eat and drink [7]. Two years later, he had further episodes that lasted 6 weeks and 10 weeks. One year later, after a brief acute illness, he again fell into a deep sleep that lasted 3 months. The nature of these prolonged sleep episodes has never been explained; however, a number of additional reports around the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries suggest that an infective cause, such as influenza, may have been responsible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree