8 | Soft Disk Herniation: Anterior versus Posterior Approaches |

| Case Presentation |

History and Physical Examination

A 38-year-old, healthy, right-hand-dominant female presented with a 1-month history of acute severe neck pain that radiated into her right shoulder, lateral brachium, lateral antebrachium, thumb, and index finger. Her neck and arm pain were both 10/10. She was not a smoker. Physical examination revealed mild weakness of the right deltoid, biceps, and wrist extensors. She had decreased sensation in the right C6 distribution. Her biceps, brachioradialis, and triceps reflexes were preserved. She had a positive Spurling sign. Her pain was not relieved by right shoulder abduction. Her lower extremity reflexes were normal. She had no Hoffmann sign and no Babinski sign, and she had a normal tandem gait.

Radiological Findings

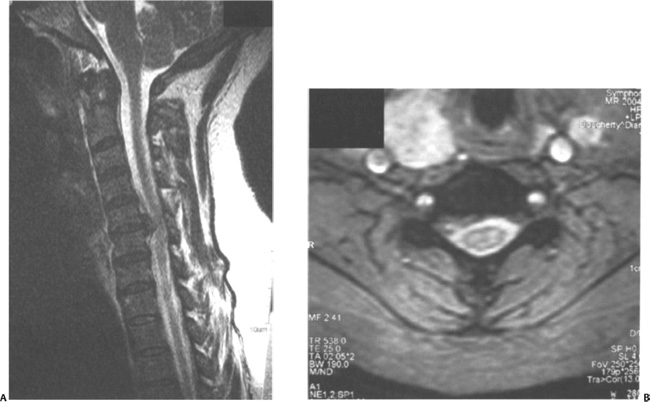

Cervical spine anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and flexion-extension views demonstrated no significant spondylosis. The disk heights were well preserved and there was no instability on flexion-extension (Fig. 8–1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine revealed a right C5-6 soft disk herniation compressing the right C6 nerve root (Fig. 8–2).

Diagnosis

Right C6 radiculopathy due to right C5-6 soft disk herniation

| Background |

Cervical radiculopathy is a clinical diagnosis based on the sclerotormal distribution of either or both motor and sensory symptoms.1 Many patients with radiculopathy initially have neck pain alone, often without any known antecedent trauma, but within a few days radicular symptoms develop.2 Compressive pathologies include anterior osteophyte, buckled ligamentum flavum, congenital canal stenosis, collapsed disk space, uncovertebral joint spur, facet osteophyte, disk herniation, instability, and spondylolisthesis as well as neurohumoral factors that can cause chemical irritation of the nerve root.1,3,4

Radiculopathy caused by soft disk herniations can be very different from that caused by hard disk herniations or osteophytic compression. Soft disk herniations often occur in younger patients with sudden onset of symptoms. In comparison, hard disk herniations have a more insidious, chronic, and progressive presentation, which may occur as osteophytes off the joints of Luschka encroach upon the neural foramen. Furthermore, hard disks arise in the setting of degenerative spondylosis, a continuum of collapsing degenerative disk disease resulting in neuroforaminal stenosis.1

Figure 8–1 Cervical spine lateral radiography demonstrates well-preserved disc heights and normal alignment.

Figure 8–2 (A) Parasagittal and (B) axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance images of the cervical spine revealed a right C5-6 foraminal/paramedian soft disk herniation compressing the right C6 nerve root.

Soft disk herniations may spontaneously improve in 80 to 90% of the patients in 6 to 12 weeks, and surgery is usually not necessary. In comparison, with hard disk herniations spontaneous improvement is less likely, symptoms are of longer duration, and surgery is often more likely. The natural history has been described by Dillin et al4 and Roth-man and Simeone,5 with estimates that slightly over half of the adult population will experience axial or radicular pain or both at some point. It has been estimated that, of the patients presenting with radiculopathy, 21.9% were caused by disk protrusions.6

Stookey7 described three different anatomical herniations that can lead to different clinical syndromes. The most common soft disk herniation is the intraforaminal herniation (or lateral herniation) and presents most often with radicular-type symptoms. In contrast, posterolateral herniations tend to present with predominantly motor symptoms, and midline herniations tend to present with myelopathy.1

Except in the face of a progressing neurological deficit, nonoperative management is appropriate in almost all cases of cervical radiculopathy.1 Although soft collar and bed rest have been treatment options in the past, there is very little in the literature to support their use. It is hypothesized that immobilization serves to decrease the acute inflammatory response. The soft collar limits range of motion and possibly minimizes irritation of the nerve root and relieves paraspinal muscle spasms. However, collars should not be used for longer than 14 days because of the rapid atrophy of the cervical musculature.1 Similarly, bed rest, thought to eliminate axial forces, should be of short duration. The inverted-V pillow and cervical traction are better suited for patients with radiculopathy. Home traction devices that apply traction forces of 8 to 12 lb can be used for 15- to 20-minute periods and are theorized to relieve pressure from compressed nerves and to increase blood flow. Cervical traction may be helpful in young patients with soft disk herniations but is less successful in patients with spondylosis.

The mainstay of conservative treatment is a concerted effort of regulated physical therapy using all modalities, pharmaceutical management, and injection therapy. Conservative treatment can be broken down in three phases. The acute phase (the first 1 to 2 weeks) treatment consists of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or a short course of oral steroids, ice or heat, activity modification, and soft collar or home traction.1 The intermediate phase (next 3 to 4 weeks) includes stretching and isometric exercises and the consideration of structured physical therapy if the patient is not responding.1 The rehabilitation phase (> 4 weeks) includes cardiovascular conditioning and a vigorous strengthening exercise program. Despite appropriate conservative treatments, between 33 and 66% of patients will experience persistent symptoms during long-term follow-up.8,9

If conservative treatment fails, surgery should be considered. The indications for surgery in patients with cervical radiculopathy are (1) persistent symptoms unresponsive to conservative management for 6 weeks, (2) disabling motor weakness of 6 weeks’ duration—loss of deltoid and wrist function would prompt surgical intervention sooner, (3) progressive neurological deficit, (4) static neurological deficit combined with radicular or referred pain, and (5) instability or deformity of the functional spinal unit in combination with radicular symptoms.3

| Methods of Surgical Management |

Anterior Cervical Diskectomy and Fusion

Robinson and Smith10 first described anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion (ACDF) in 1955. This technique used an autogenous tricortical iliac crest graft shaped like a horseshoe. The cortex helps to maintain disk space height while the cancellous bone facilitates fusion. This technique has been modified many times in the literature.11–15 In 1958, Cloward12 developed an oversized dowel graft for fusion. However, this method often led to graft collapse with a kyphotic deformity. In 1960, Bailey and Badgley11 developed a corticocancellous structural graft that was structurally superior to the Cloward but inferior to the Smith and Robinson. In 1969, Simmons and Bhalla15 described a trapezoidal graft that theoretically decreased the risk of extrusion. Lastly, Emery14 modified this technique by burring the end plates for a more aggressive decortication. It was thought that this technique prevented spondylotic spurring, promoted spur resorption, allowed for indirect decompression of the spinal canal, and minimized surgical manipulation of the neural structure.10

Radiographic and clinical results after ACDF have been generally good. Robinson et al16 reported an 88% fusion after ACDF compared with 95% by Emery14 with his modified technique. Herkowitz et al17 prospectively found that 94% of patients undergoing ACDF had good or excellent results, whereas Lunsford et al18 found that 67% of patients had good or excellent results. Clements and O’Leary19 showed 88% to have good or excellent results when the symptomatic levels were treated with no additional spondylosis found at adjacent levels. Degenerative arthritis may develop both above and below the fusion, though it can remain asymptomatic.20

Autogenous iliac crest has been the standard fusion bone graft since Robinson and Smith10 and Cloward12,21 first introduced its use in the 1950s. Nonunion rates have been reported to be 3 to 20% for single-level fusions, up to 27% for two-level fusions, and up to 50% for three-level fusions.4,10,16,21–24 The use of allograft has been shown to give similar fusion rates to autograft for single-level fusions.12,25–27 However, significantly higher nonunion rates ranging up to 63% have been observed for multiple-level procedures with allograft.26 In a prospective series, An et al27 showed that 33.3% of levels developed pseudarthrosis with allograft-demineralized bone matrix compared with 22% with autograft. More recently, Yue et al28 noted in a series of 71 patients treated with allograft/plate and followed for an average of 7.2 years, 82% remained symptom free and 93% achieved a solid fusion. Furthermore, Samartzis et al29 noted in a series of 66 patients with single-level ACDF that a solid fusion was obtained in 100% of the allograft patients versus only 90% in the autograft patients. This difference was not statistically significant, however.

Posterior Cervical Laminoforaminotomy

Successful treatment of cervical radiculopathy via a posterior approach was first described by Spurling and Scoville30 in 1944. A keyhole laminoforaminotomy involves removal of bone from the adjacent lamina and overlying facet joint to allow direct visualization of the involved nerve root.31 Proponents of this approach cite its ease and comparable outcomes to the anterior approach while obviating the need for fusing the motion segment and avoiding its potential complications.3

A concern with posterior laminoforaminotomy is the potential to create iatrogenic instability by overzealous bony resection. A biomechanical study by Zdeblick et al32 evaluated bilateral facetectomies and their effect on cervical stability. They found stability was maintained with bilateral facetectomies up to 50%, allowing a 3 to 5 mm exposure of the nerve root. Beyond 50%, shear strength reduced significantly, resulting in increased instability.

Successful treatment of cervical radiculopathy by posterior laminoforaminotomy has been reported in numerous publications. Henderson et al33 reviewed 846 consecutive cases between 1963 and 1980 and reported relief of significant arm pain/paresthesias in 96% of patients and complete resolution of motor deficits in 98% with overall good or excellent outcomes in 91.5%. In a smaller study, Simeone and Dillin34 reported a 96% success rate in 50 patients. In a study of 183 patients who underwent surgery in an outpatient setting, Tomaras et al35 reported 92.8% good or excellent outcomes in those patients not involved with worker’s compensation. Success rates decreased to 77.8% in those with worker’s compensation claims. Their study showed that this procedure can be done on an outpatient basis with comparable results to inpatient surgical management. In a prospective study comparing the anterior and posterior approaches, Herkowitz17 reports 94% (16 of 17) good to excellent results with anterior diskectomy and fusion versus 75% (12/16) good to excellent results. The difference, however, was not statistically significant.

| Selecting a Method of Surgical Management |

For single-level soft disk herniations, both anterior and posterior (laminoforaminotomy) approaches have been shown through numerous studies to be quite successful, with neither technique proving to be statistically superior to the other.11,16,34,35,40,41 ACDF provides good visualization of the entire pathological disk and allows indirect decompression of the neural foramen without manipulation of the neural elements. Posterior laminoforaminotomy allows direct decompression of the nerve root and obviates the need for fusion and postoperative cervical immobilization, which may be appropriate for younger patients unlikely to have concomitant spondylotic changes. A third viable surgical treatment option may be cervical disk replacement. At this writing, however, cervical disk replacements are not Food and Drug Administration approved.

The choice of approach should be based on the presenting clinical symptoms and its correlation to pathological changes seen on neurodiagnostic studies. Generally though, the choice of technique will likely be based on patient and surgeon preference.

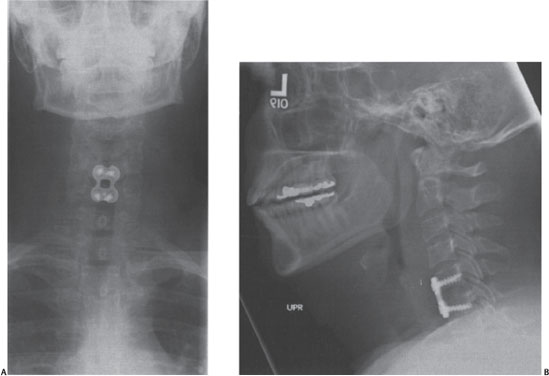

Figure 8–3 (A) Postoperative anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiographs reveal the C5-6 anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion with tricortical iliac crest allograft and plate.