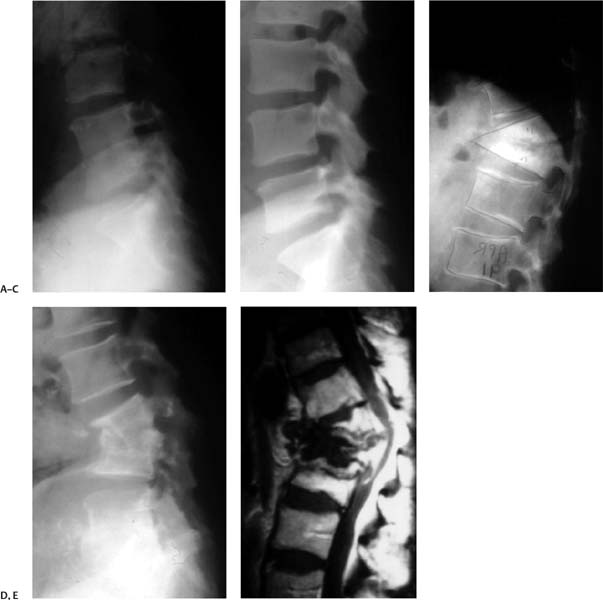

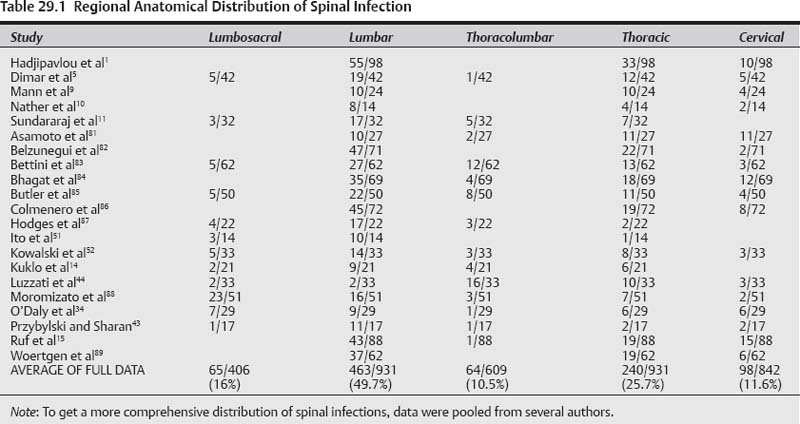

29 Spinal infection encompasses several entities with characteristic presentations and clinical courses1; it can be pyogenic (bacterial), granulomatous (tuberculosis or fungal), or parasitic. Spinal pyogenic infection can be either primary or secondary after any invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedure (surgery, diskography, epidural steroids, etc.). Structural localization of primary spinal pyogenic infection has been identified as spondylodiskitis (95%), diskitis (1%), spondylitis (1%), pyogenic facet arthropathy (6%), and primary epidural abscess (2%).1 The concept of spondylitis (denoting osteomyelitis of the vertebral body) originates from the theory that, in adults, infection starts in the subchondral bone as an osteomyelitic lesion and then spreads into the adjacent intervertebral disk.2 In the early stages, at least some of these entities may represent different phases of a wider spectrum of the same infectious process in a state of evolution, with spondylodiskitis being the major segment of the spectrum of spinal infections—as first expressed by Ghormley and associates.3 When an epidural abscess complicates pyogenic infection of the spine it is referred to as secondary epidural abscess. It is estimated that the incidence of spondylodiskitis in the general population is 1.8 cases per 10,000 hospital admissions, and the incidence of paraplegia represents 20.9 cases per 10,000 spinal cord injuries.4 Frequent complications of spondylodiskitis are spinal deformity (Fig. 29.1), spinal instability, and epidural abscess that clinically may result in variable degrees of back pain, neck pain, radiculopathy, paraparesis, paraplegia, severe morbidity, and mortality. The real question is: can these complications be prevented and what are the best treatment options? Several conditions have been accepted as risk factors pre-disposing to primary hematogenous spinal infection. There are no good scientific studies to grade the degree of their virulence. However, based on the available literature they can be graded into three categories.5–11 Category I includes the origin of the source of infection such as preceding infection, IV drug abuse, diagnostic, or surgical procedures. Category II comprises predisposing medical conditions that render the host susceptible to infection such as immunosuppressive host, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic steroid use. Finally, category III consists of comorbidities (organ failure, ankylosing spondylitis, trauma, etc.). The most frequent anatomical location (Table 29.1) of spondylodiskitis was the lumbar spine (49.7%) followed by the thoracic (25.7%) and cervical spine (11.6%). The most frequent anatomical site for thecal sac encroachment by epidural abscess was in the cervical spine (90%) followed by the thoracic (33%) and lumbar spine (23.6%).1 However, dreadful neurological complications (paraparesis/paraplegia) as a result of thecal sac compression occurred more frequently in the thoracic (81.8%) and cervical (55.6%) regions as opposed to the lumbar (7.7%) spine.1 Therefore, in case of cervical or thoracic infection, more caution should be exercised to assess the higher probability of secondary epidural abscess formation and prevent its grave neurological consequences. Primary epidural abscess is reported to occur at rates ranging from 5.7 to 29%,1,12,13 whereas secondary epidural abscess is more frequent, and the reported rates range from 38 to 94.2%.1,12,13 The most dreaded complication is paralysis (Table 29.2). When paraplegia or tetraplegia is present, the prognosis for recovery is very poor. In Hadjipavlou et al’s series, 37% of the patients with epidural abscess presented with paraplegia.1 Only 23% recovered completely, and 7.7% had a partial recovery from paraplegia. Pearls • Infection in the cervical and thoracic spine is more prone to develop epidural abscess and serious neurological deficit. • The prognosis for recovery from paralysis is very poor, and surgery should not be delayed in the presence of serious or deteriorating neurological deficit. Fig. 29.1 Demonstration of different pathways of spondylodiskitis end results. (A) Early infection. (B) Successful fusion of adjacent vertebrae with some degree of kyphosis and manageable backache. (C) Serious kyphotic deformity with crippling back pain. (D) Spinal canal compromise with variable degree of neurological deficit. (E) Complete paraplegia. Spondylodiskitis is commonly managed nonoperatively with intravenous antibiotics and external support. However, when it is complicated with neurological impairment, abscess formation, recurrence of infection, severe pain, segmental instability and/or local kyphosis, and absence of clinical response, surgical intervention is indicated. It is generally agreed that the administration of antibiotics is warranted. But the dosage, route, and duration of antibiotic therapy advocated by various investigators are still imprecise. Some authors advocate 6 to 8 weeks of intravenous therapy alone, whereas others propose 6 to 8 weeks of parenteral therapy followed by 2 months or more of oral therapy, depending on clinical and laboratory response (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein values).1,14–17 Even after adequate debridement and instrumentation, delayed recurrence of infection may occur because the primary infection is not completely eradicated or because of the occurrence of a de novo secondary infection.18 The contributing factor should be attributed to virulent micro-organisms and resistance to local antibiotics.19 For instance, patients that are hospitalized or have leg ulcers are at high risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and elderly patients with recurrent urinary tract infections and IV drug users are at high risk for gram-negative bacilli. Generally, treatment should cover MRSA with vancomycin or teicoplanin, and gram-negative bacilli with ciprofloxacin or third-/fourth-generation cephalosporin.20,21 In general, immunocompromised patients require longer treatment. When treatment is delayed for a mean of 6 to 7 weeks after the onset of symptoms, antibiotic treatment for 4 to 8 weeks is associated with an increased recurrence rate as compared with treatment for 12 weeks and over.22 When treatment starts within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms, a 6-week treatment is adequate.22 Table 29.2 Incidence of Paralysis in Patients with Spondylodiskitis

Spine Infections: Medical versus Surgical Treatment Options

Treatment of Spinal Infections

Treatment of Spinal Infections

Conservative Treatment

Study | % (N) |

|---|---|

Hadjipavlou et al1 | 17.0% (17/101) |

Lee and Suh7 | 38.8% (7/18) |

Malawski and Lukawski8 | 5.2% (23/442) |

Mann et al9 | 55.5% (10/24) |

Nather et al10 | 7.1% (1/14) |

Sundararaj et al11 | 41.1% (15/37) |

Asamoto et al81 | 55.7% (15/27) |

Butler et al85 | 6.2% (3/48) |

Ruf et al15 | 28.1% (20/71) |

Allen et al29 | 57.0% (8/14) |

TOTAL | 14.9% (119/796) |

Obtaining a biopsy, before antibiotic administration, for culture and histology is crucial for administering the appropriate antibiotics.1,16,23

Pearls

• Tissue culture is crucial for administering the appropriate antibiotics.

• Weak evidence recommends treatment with intravenous antibiotics for 6 to 8 weeks.

• Other level IV studies recommend 2 or more months of oral antibiotics following treatment with IV antibiotics.

Conservative versus Surgical Treatment

Bony ankylosis after conservative treatment may take up to 2 years and occurs only in 35% of cases.24 Furthermore, most of the patients frequently complain of residual mechanical back pain.25,26 It is notable1 that 64% of patients treated by medical means complained of mechanical back pain as opposed to 26% of patients treated surgically.

A retrospective analysis of 57 patients with epidural abscess treated with antibiotics alone (25 patients) or in combination with computed tomographically (CT) guided percutaneous needle aspiration (seven patients) and open surgical drainage (28 patients), concluded that epidural abscess can be treated safely and effectively with antibiotics alone.27 However, this study had several flaws ranging from patient selection to lack of randomization. Furthermore, residual chronic pain from deformity, a major complication of spondylodiskitis, was not taken into account in this study.

A recent study (level IV) has displayed more uncertainty on the efficacy of nonoperative treatment. Nineteen patients with spondylodiskitis (eight complicated with an epidural abscess and three with a subdural abscess) were treated with antibiotics and bracing alone for an in hospital duration of 58.2 ± 22.0 days.28 The authors claim successful medical outcome; however, two patients died of uncontrollable sepsis and no objective outcome measures were utilized. Furthermore, the clinical presentations were not well documented, and one wonders why the authors continued to treat patients suffering from sepsis and paraplegia with antibiotics alone.

There are no prospective, randomized studies or sufficient data in the literature to compare the outcomes of conservative versus surgical treatment. Furthermore, most of the cases that are referred for surgical treatment are patients with severe painful deformities and neurological complications for whom surgery is the best treatment option.

Some authors noted a recurrence of infection even as late as several years after surgical treatment, ranging from 2 to 18%.1,25,29,30 However, the majority of published surgical outcomes have not indicated late recurrences of deep infection.5,16,25,29–33

There are inadequate published data on the long-term functional outcomes after pyogenic spinal infection.34 Most studies have used heterogeneous, unreliable, and nonvali-dated measure instruments yielding data that are difficult to interpret.

Poor functional outcome following pyogenic spinal infection is common at long-term follow-up even in patients with apparent complete neurological recovery.

Pearls

• There are no prospective, randomized studies comparing surgical versus conservative treatment; however, it appears that surgical treatment was performed in patients with severe painful deformities and neurological complications.

• Weak studies suggest that patients treated solely by medical means are more prone to complain of mechanical spinal pain as opposed to surgically treated patients.

Surgical Treatment

Although pyogenic spinal infection comprises less than 4% of all bone infections, it can be a challenging condition to successfully manage surgically due to moribund patients, destructive lesions resulting in spinal deformity, profound local inflammatory response, and cord compression.

Early accounts of surgery for spinal infection were associated with a significant morbidity rate and comparatively high incidence of recurrent infections. Improved methods of radiological diagnosis, safer operative and anesthetic techniques, and modern segmental spinal fixation systems have led to better overall surgical outcomes.

It is widely agreed that radical and aggressive debridement of all unhealthy material is mandatory for successful results.35 All infected and necrotic tissues must be excised and abscesses evacuated. Surgery usually offers relief of severe pain, restoration of neurological impairment, and improvement or maintenance of sagittal balance.1,14,15,31,35–41

Pearls

• Surgery is very effective for improving sagittal balance, restoring neurological impairment, and relieving severe pain.

Conventional surgery

Several methods and surgical approaches have been advocated. These include (1) anterior approach alone consisting of anterior decompression and bone grafting, that is occasionally enhanced with anterior stabilization; (2) posterior approach consisting of laminectomy alone or further supported by transpedicular instrumentation; (3) combined anterior decompression, bone grafting, or cages through a thoracotomy or retroperitoneal approach with posterior stabilization either as a staged procedure or in the same sitting; (4) posterior extracavitary approach, which can also achieve an anterior decompression and posterior stabilization.

Anterior, posterior, or Combined Approach?

There are some issues concerning surgical approaches (e.g., strategy of the procedures for the best optimal treatment, the type of instrumentation, and graft material). The selection of anterior versus posterior approach is still a matter of debate. Because the pathology of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis affects mainly the vertebral bodies and disk spaces, the anterior approach is adopted by many surgeons because it allows direct access to the infected focus and is convenient for debriding infection and reconstructing the defect with greater stability.25,35

The majority of anterior surgical approaches are performed in patients with cervical lesions. In the lumbar and thoracic spine, anterior instrumentation to provide bone stability after grafting may be tenuous39 because the concomitant osteoporosis associated with infection renders the vertebrae structurally weak and may prevent adequate fixation.

However, most operations are currently performed using a combined approach. There is a decrease in the incidence of recurrence of infection and revision surgery with combined approaches as compared with a single approach.14,42 The relatively larger invasiveness of combined anterior and posterior approach surgery has not been shown to worsen the morbidity and mortality of the procedure.

Pearls

• Most surgeons favor an anterior surgical approach for managing pyogenic spondylodiskitis, particularly in patients with cervical lesions.

Single-Stage versus Two-Stage Operation

Controversy remains on the subject of one- or two-stage operation. Two-stage operation with a convalescence period bridging the two surgeries may result in shorter operation time, less blood loss, and safety for the patient with poorer general health.42 On the other hand, a single-stage operation also has many advantages, such as lower complication rate, shorter hospital stay, and earlier mobilization.14,16,17,37,40

In a small series of cases comparing anterior versus combined anterior and posterior instrumentation, Hee et al35 showed the combined approach had better overall results in terms of postoperative complications, quicker fusion, and maintenance of kyphotic correction.

Combined surgical approaches in a sequential fashion have been shown even in moribund patients to be a safe approach.1,16,44 Most authors1,14,15,34,36,43 agree that a single-stage procedure generally outweighs the perceived surgical risks.31,43 However, the procedure could be staged for severely unhealthy patients. Nevertheless, the possibility to perform limited invasive posterior, anterior, or combined stabilization should result in minimizing intraoperative bleeding and postoperative complications.14

Poor sagittal spinal correction has been documented following anterior debridement and fusion without instrumentation.2 In the last few years, improved correction of sagittal alignment has been noted with anterior strut grafting, structural allograft, and titanium mesh cages combined with posterior instrumentation.1,16,18,32,41,45 Reported kyphosis correction ranges from 7.2 to 12.7 degrees, with 2.0- to 3.0-degree loss of correction with an average follow-up of 45 months.14,16,25,33,41

Pearls

• Weak studies advocate combining anterior and posterior approaches in a single-stage procedure because it is associated with lower complication rates, shorter hospital stay, and faster patient mobilization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree