Spondylolisthesis and Bracing: A Critical Literature Review

Tom Bendix

Spondylolisthesis means sliding (-olisthesis) of the spine. There are mainly three types: spondylolytic, degenerative, and congenital (1,2). This chapter describes the types with regard to the possible effect of corseting or bracing and reviews the literature review on evidence found with bracing.

A brace is a stiff, body-conforming device intended to prevent or reduce movement. A corset is a fabric-based device that can be made more or less stiff by means of metal or plastic inserts. It is not as stiff as a brace.

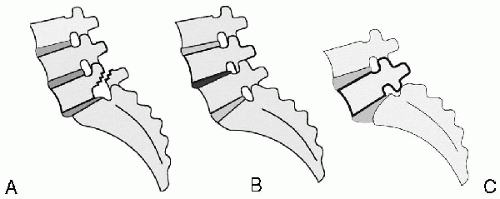

Spondylolisthesis is seen in children above the age of 6 in whom spondylolysis at the fifth lumbar (L5) vertebra has resulted in forward sliding of the anterior aspect of L5 vertebra and the spine above (Fig. 14.1A). L4-L5 degeneration may lead to spondylolisthesis, usually above the age of 60 if, additionally, the facet joints are malformed prior to or during the period of instability (Fig. 14.1B). Furthermore, it is seen (albeit rarely) in early childhood as a result of a congenital, dysplastic dome-shaped deformation of the base of the sacral bone in combination with insufficient facet joints.

The dysplastic type virtually always progresses to the extent that surgery is the treatment of choice and a brace for primary treatment is out of the question. This type is very seldom seen and will not be considered further in this review. Other chapters in this book provide further details on classification.

SPONDYLOLYTIC SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

Spondylolysis virtually always appears in the early teen years and is most often caused by a fatigue fracture in the isthmic area (2,3). The pure spondylolytic type without spondylolisthesis is apparently rarely symptomatic, since it is often clinically evidenced later in life without the patient having any memory of pain.

There seem to be several different clinical courses:

Symptoms occur at the time the fracture appears. Probably this is the type that is treatable with a brace (see later discussion).

Back pain occurs around the age of 20.

Back pain occurs later in life, most often in the 30s,when spondylolisthesis is noticed for the first time.

The condition is never symptomatic.

Fracture pain as seen in any other fractures in the body is most likely the cause of the first mentioned, early type. Spinal instability is considered to be the cause of pain for the

type at age 20. The more spondylolisthesis, the more likely the appearance of symptoms during the young years.

type at age 20. The more spondylolisthesis, the more likely the appearance of symptoms during the young years.

When spondylolytic spondylolisthesis becomes a part of the clinical picture later in life, it seems related to discogenic pain, more often in L4-L5 than L5-S1.

The reason for the absence of pain despite large deformation could be the following: L5-S1 disc becomes highly deformed at an early stage and consequently severely degenerated. In most cases, the degeneration is so intensive that the nucleus degenerates quickly, changing from a jelly consistence to fibrotic tissue. One result is that the phase in the degenerative process when annular tears can be penetrated by jelly nuclear material does not occur (4). Therefore, the altered anatomy may instead influence the L4-L5 level, because that joint will receive increased demand during lumbosacral movements. Probably, this L4-L5 pathology does not differ from any other discogenic pain.

Pain and spondylolisthesis are more often associated in girls than in boys (5).

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

The degenerative type of spondylolisthesis in later age seems highly related to spinal instability, but because this is based on discogenic components in terms of annular tears, it is difficult to distinguish what is actually the cause of a back pain. Also facet-joint pain, secondary to the reduced segmental stability, may contribute to the back pain (6). Due to anterior displacement of one part of the vertebral canal—the neural ring of L4—in relation to that of L5, the canal may be narrowed at that level, resulting in usual leg-pain claudication symptoms of spinal stenosis. Also facet-joint arthrosis and soft tissue components secondary to the reduced disc height usually contributes to this stenosis.

RATIONALE FOR AND AGAINST BRACE IN SPONDYLOLYSIS/SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

The theoretical biological effect of a brace is an ability to avoid painful movements. Such movements can be either:

Instability

Abnormal joint-mobility within the normal range of movement (ROM), or

Abnormal large trunk movements

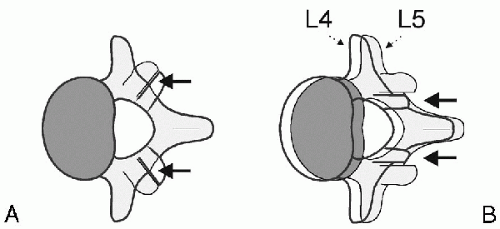

FIG. 14.2. A: Normal facet-joint orientation would not allow L4 to slide forward. B: A modification of the joint is mandatory and possible (although not exactly as shown in this schematic drawing). |

In these cases, unexpected positioning in the course of a movement implies abnormal, uncontrolled tensions of various tissues. Instability has been studied for years, but despite a theoretical definition, no clear, clinically usable test for demonstrating instability has yet been stated. However, it seems as if lack of smoothness in the course from one endpoint to another (described in list item la above) is a key issue, dominated by rather erratic movements.

2. Movements can also be painful in a normal movement pattern due to irritation of local receptors in deteriorated tissues, as in osteoarthritis.

The theoretical effect of a brace would be that it might be able to avoid some of these painful movements. However, at least small midrange movements do not seem to be prevented by bracing (7) and corseting offers even less prevention of movement. It could be that larger movements could be relieved to some extent. In a study (8), Spratt et al. demonstrated that bracing gave a better clinical result for a lordotic posture than for flexion/ kyphosis. They hypothesized that the (slight although seemingly present) effect did not relate to possible instability but rather to the component of discogenic pain based on annular tears. Spratt et al. did look into degenerative spondylolisthesis versus retrodisplacement, but the sample was too small for subgrouping. In the present author’s conception, their result may correspond well with the later demonstrated effect of extension exercises, improving those initially centralizing their pain (9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree