Chapter 17 “The brain cells are dying faster than you are thinking.” Early management of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is best conducted in an environment that is conducive to prevention, early recognition, and preemptive management of complications. The early phase of AIS requires management of both neurologic and nonneurologic factors. Central nervous system issues can be divided into protection of the newly restored perfusion as well as prevention or treatment of the complications secondary to the original ischemic insult. The highest mortality from AIS is present during the first weeks after the stroke; in the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study (NOMASS), the early mortality rate from AIS approached 75%.1 Impaired consciousness on admission, vertebrobasilar involvement, and early transtentorial herniation are the most significant predictors of higher mortality.2 Increasing age has also been identified as an independent factor for increasing medical complication and mortality rates (Table 17.1).3 The Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) and NIH Stroke Scale Score (NIHSS) are major predictors for instability during the early phase of management. With every point increase in NIHSS score, one can expect a 24% reduction in the ultimate outcome quality.4 It has become clear with experience that when the NIHSS score approaches and exceeds 16, the risk for complications is high, the ultimate neurologic outcome is predictably worse, and the patient will benefit from admission to the neurocritical care unit. Expert neurocritical care skills are beneficial to preempt and reverse cerebral edema and medical complications in this setting. Multiple factors can affect the immediate stabilization of patients with AIS. Premorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, unstable coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal failure and congestive heart failure must be appreciated and addressed. In addition, the affected vascular territory can have a significant impact on complication and mortality rates, with complete middle cerebral artery infarctions carrying a high risk of malignant cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension. Posterior circulation stroke may be complicated by airway compromise due to lower cranial nerve involvement or direct insult to or compression of brainstem respiratory centers. Prior to interventional attempts to restore cerebral perfusion, several measures must be taken to stabilize airway, breathing, and circulation. Although early recanalization of a major arterial occlusion takes precedence over most other interventions, patients with airway compromise require immediate establishment of an adequate airway, often via endotracheal intubation. It is important to perform a quick and complete neurologic examination before intubation as sedation or paralysis will confound the ability to properly document the neurologic condition. Prior to intubation, patients should be preoxygenated, and preferably two suction catheters should be prepared. Most patients have eaten within the previous 6 to 8 hours, thus rapid sequence induction with lidocaine is the most appropriate approach. We prefer to avoid the use of a paralytic agent, which may impair our ability to monitor the patient’s neurologic exam. Etomidate is our drug of choice for sedation (0.3 μ g/kg), followed by low-dose propofol or dexmedetomidine infusion. Endotracheal tube placement should be confirmed objectively with a chest radiograph. If the patient is hypotensive, end tidal CO2 may give a false indication of low exhaled CO2, which may also result from massive pulmonary embolism.

Stabilization of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke

Early Stabilization of Acute Ischemic Stroke

Early Stabilization of Acute Ischemic Stroke

Preintervention Stabilization

Airway and Oxygenation

Impaired consciousness on presentation |

Posterior circulation acute ischemic stroke |

Cerebral herniation syndrome |

Advancing age |

Acute cerebral edema |

Respiratory failure requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation |

Acute myocardial infarction |

NIH Stroke Scale Score ≥16 |

One can start with 100% FiO2 either with a nonrebreather mask or with mechanical ventilation. Oxygen saturation is kept close to 100%, and FiO2 is titrated down based on the saturation. Blood gases may be checked to confirm PaO2 is consistent with saturation.

Circulation: Cerebral Perfusion Pressure and Blood Pressure

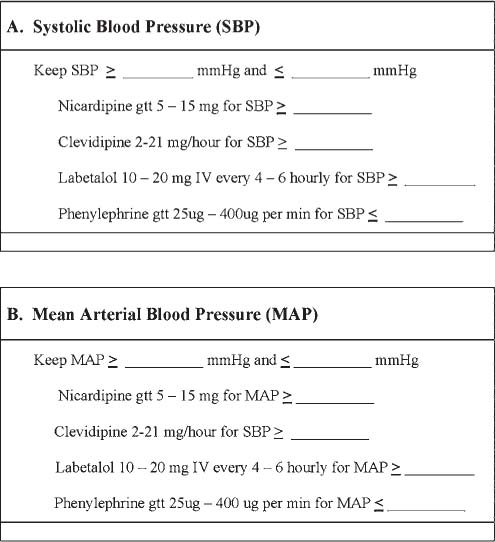

Fig. 17.1 Proposed protocol for blood pressure control in neurocritical care.

Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) depends on mean arterial pressure (MAP). MAP is kept within the area under the curve (AUC) by carefully controlling the blood pressure itself. We use nicardipine or clevidipine and avoid reducing the systolic blood pressure (BP) and MAP below 25% of baseline. If the CPP drops below the AUC, phenylephrine, 25% albumin, or hypertonic saline can be used. In the tPA stroke survey, pretreatment BP was one of the main factors associated with an increased fatality rate and was also related directly to the risk of hemorrhagic conversion.5 In our experience, the placement of an arterial line for real-time monitoring is helpful in the early management of uncontrolled BP.

In the International Stroke Trial (IST), abnormal systolic BP and MAP were directly related to poor outcome at 6 months. The early mortality rate was increased by 3.8% for every 10 mm Hg above 150 mm Hg and by 17.9% for every 10 mm Hg below 150 mm Hg.6 Figure 17.1 provides a representative standardized order set as used by our neurovascular service for BP control in the setting of AIS.

Postintervention Stabilization

Following intervention to attempt reperfusion of the involved territory, we continue the above protocols. In addition, the below mentioned measures are implemented. The neurocritical care management can be very complicated with multiple variables (Table 17.2).

Pulmonary |

COPD with baseline hypoxemia |

Acute bronchospasm |

Respiratory failure |

Aspiration pneumonitis |

Acute thromboembolism with paradoxical emboli |

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome |

Cardiac |

Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response |

Decompensated congestive heart failure |

Aortic stenosis–severe with fixed cardiac output |

Prosthetic cardiac valve with anticoagulation |

Renal |

Renal transplant with immunotherapy |

Renal failure with fluid restriction |

Metabolic |

Diabetes mellitus with DKA or hyperglycemia |

SIADH |

Cerebral salt wasting |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DKA, diabetes ketoacidosis; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone.

Glucose Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree