5 Status Epilepticus

Jan Claassen and Lawrence J. Hirsch

Status epilepticus (SE) is a life-threatening medical and neurological emergency and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. Every hour delay in treatment increases mortality. Traditionally, SE has been defined as continuous or repetitive seizure activity persisting for at least 30 minutes without recovery of consciousness between attacks. Nowadays, patients should be considered to be in SE if seizures persist for more than 5 minutes.1 SE may be classified into convulsive and nonconvulsive based on the clinical presence of seizure-like activity.

In neuroscience intensive care units, up to a third of patients will have nonconvulsive seizures (and most of these patients will be in nonconvulsive status epilepticus [NCSE]).2 In the medical intensive care unit, up to 10% of patients undergoing continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring have nonconvulsive seizures.3 Up to 50% of patients with generalized tonic-clonic seizures will have nonconvulsive seizures after convulsions have subsided. The annual incidence of SE is 100,000 to 200,000 cases in the United States. Refractory status epilepticus (RSE) is defined by failure to respond to two intravenous drugs and occurs in up to 43% of patients with SE.4,5

The most common cause of SE is a prior history of epilepsy (22 to 34%). Other causes include remote brain lesion (stroke, tumor, or subdural hemorrhage [SDH], etc., 24%), new stroke (22%), anoxia/hypoxia (10%), metabolic (10%), and ethyl alcohol (EtOH) withdrawal (10%).6

History and Examination

History

- Seizure semiology. Obtain a detailed description of the seizure (gaze deviation, face or extremity jerking, automatisms, altered mental status, etc.).

- Seizure duration. Attempt to establish when the patient was last seen normal as an onset time. Determine duration of convulsive component of seizure and duration of postictal or potentially nonconvulsive period of altered mentation.

- Past medical history of epilepsy or epilepsy risk factors (history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, meningitis/encephalitis, or febrile seizures); history of hypoglycemia or diabetes, history of structural brain lesion (stroke, tumor, subdural, etc.)

- If epileptic, determine what antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) the patient was taking and if there is a history of noncompliance.

- Medication history (review medications that reduce seizure threshold)

- Social history, with particular attention to illicit drug use or EtOH use

- A full neurologic examination, including assessment of mental status, cranial nerves, motor skills, and reflexes, as well as a sensory and cerebellar exam, should be performed in all patients.

- Mental status. Typically, patients who present with generalized convulsive SE are expected to awaken gradually after the motor features of seizures disappear. If the level of consciousness is not improving by 20 minutes after cessation of movements, or if mental status remains abnormal 30 to 60 minutes after the convulsions cease, NCSE must be considered, and urgent EEG monitoring is advised.

- Symptoms may include:

- Negative symptoms such as coma, lethargy, confusion, aphasia, amnesia, speech arrest, and staring

- Positive symptoms such as automatisms, blinking, facial twitching, agitation, nystagmus, eye deviation, and perseveration

- It is crucial to recognize and treat NCSE early because prognosis worsens with increasing duration of seizure activity.

- Focal exam findings. Todd’s paralysis and Todd’s-equivalents, such as aphasia, numbness, etc. Any focal finding indicates a potential focal brain lesion.

Differential Diagnosis

- Status epilepticus and/or NCSE

- Postictal state—if mental status remains abnormal 30 to 60 minutes after the convulsions cease, NCSE must be considered, and urgent EEG is advised.

- Movement disorders (myoclonus, asterixis, tremor, chorea, tics, dystonia)

- Herniation (decerebrate or decorticate posturing)

- Limb-shaking transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), most commonly associated with perfusion failure due to severe carotid stenosis

- Psychiatric disorders (psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, conversion disorder, acute psychosis, catatonia)

- Any condition that may lead to decreased level of consciousness (e.g., toxic-metabolic encephalopathies, including hypoglycemia and delirium, anoxia, and central nervous system [CNS] infections), transient global amnesia, sleep disorders (e.g., parasomnias), syncope

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

- Status epilepticus and NCSE

Diagnostic Evaluation

- EEG. Urgent EEG is indicated in any patient with fluctuating or unexplained alteration of behavior or mental status, and after convulsive seizures or SE if the patient does not rapidly awaken.

- Spot EEG (30-minute recording) picks up about one-third of nonconvulsive seizures (using 24-hour EEG as a gold standard), and about half of clinical events.

- Limited montage (6-channel or hairline EEG) is not sensitive for seizures or epileptiform discharges.

- Continuous EEG (cEEG) is preferred. Twenty-four hours of monitoring detects 95% of seizures in noncomatose patients and 80% in comatose patients (comatose patients should have cEEG for 48 hours before nonconvulsive seizure is ruled out).7

- Video EEG monitoring is helpful to distinguish true electrographic activity from common ICU artifact (ventilator, continuous venovenous hemofiltration [CVVH], nursing-related artifact).

- EEG findings in the aftermath of SE may include generalized periodic epileptiform discharges (GPEDs), periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs) or bilateral but independent periodic discharges (BiPLEDs). These controversial EEG findings in the setting of SE may be considered on an ictal/interictal continuum because they do not meet formal seizure criteria, and their exact nature and significance are not well understood.

- Benzodiazepine trial. May help to make the diagnosis of NCSE. Administer sequential small doses of rapidly acting, short-duration benzodiazepines (e.g., midazolam 1 mg). Resolution of the potentially ictal EEG pattern and either an improvement in the clinical state or the appearance of previously absent normal EEG patterns would be considered a positive response. If EEG improves but the patient does not (e.g., due to marked sedation), the result is equivocal.

- Imaging studies

- MRI: Seizure focus may show up as a bright signal on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dark signal on apparent diffusion coefficient imaging (ADC) in a nonvascular territory possibly with leptomeningeal enhancement. Gyral increased signal and gyral thickening are sometimes seen on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and is a reversible change. This pattern may mimic acute infarction.

Treatment

General Concepts

- Treat quickly. Eighty percent of patients will respond to first line medications if treatment is begun within 30 minutes, but <40% respond if treated within 2 hours. Mortality doubles with a 24 hour delay in treatment of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.8

- Do not withhold seizure medications because of fear of respiratory suppression leading to intubation. When given by paramedics for out-of-hospital SE in adults, the rate of respiratory depression or circulatory complications was lower with lorazepam and diazepam than with placebo.9 These, as well as other studies, confirm that not giving benzodiazepines is riskier than giving them for prolonged convulsive seizures.

First-Line Antiepileptic Medications

Lorazepam is superior to phenytoin or diazepam as a first line agent.10 In a trial comparing four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus, lorazepam aborted 65% of seizures, phenobarbital 58%, phenytoin + diazepam 56%, and phenytoin alone 44%.11 A randomized trial comparing lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus found status epilepticus was terminated more frequently with lorazepam or diazepam compared with placebo. There was a trend for more seizure termination with lorazepam compared with diazepam, but this was not statistically significant.9 Lorazepam is preferred as first line over diazepam because it has a longer duration of action (4 to 6 hours) and less fat distribution. If no IV access is available, diazepam is available in a rectal form, and midazolam can be given buccally or intranasally.

Second-Line Antiepileptic Medications

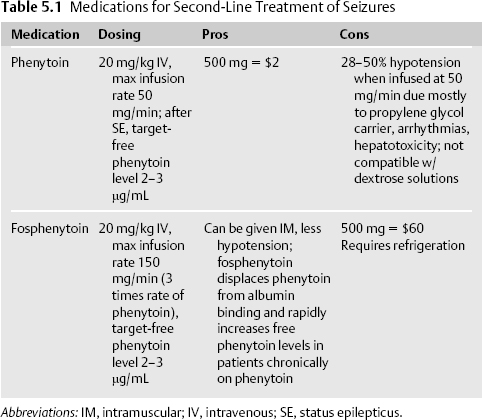

Due to the time-dependent loss of potency of lorazepam and the need for a maintenance antiepileptic drug (AED), phenytoin or fosphenytoin is typically administered even if seizure activity has stopped after lorazepam is given. Fosphenytoin is usually used as a loading agent, particularly when a patient is still seizing. Because of its cheaper cost, phenytoin is used as a maintenance agent (Table 5.1).