CHAPTER 10 Stress and coping

The material in this chapter will help you to:

What is stress?

Stress is a physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural reaction of an individual (or organism) to a stressful event – stressor – that threatens, challenges or exceeds the individual’s internal and external coping resources. The threat may be actual (e.g. being robbed at knife point) or perceived (e.g. the student who believes he will fail a forthcoming exam). The threat or stressor can be physically or emotionally challenging, or both. It may also be perceived as either a positive or negative event by the individual (Witek-Janusek & Barkway 2004). See Figure 10.1 for examples of physical and emotional stressors.

Table 10.1 Examples of stressors

| PHYSICAL STRESSORS | EMOTIONAL STRESSORS |

|---|---|

| Undergoing surgery | Diagnosis of a chronic disease |

| Insomnia | Marriage |

| Loss of eyesight | Travel overseas |

| Heat stress | Redundancy |

| Physical trauma | Relationship breakup |

| Pain | Moving house |

| Illness | Winning the lottery |

Stress as a response, stimulus or process

Stress is a topic of interest not only to health professionals but also to the general public as evidenced by the number of publications on the topic in the pop psychology literature such as in self-help books and health and lifestyle magazines. Furthermore, stress is the most investigated phenomenon in health psychology research with regard to examining the relationship between psychology and disease (Lyons & Chamberlain 2006). Despite this not all researchers use the concept in the same way. Research that investigates the relationship between stress and health fall into three main categories that view stress as one of the following:

Stress as a response

Stress as a response refers to the individual’s physiological and psychological reactions to a perceived threat or stressor, such as the student who discovers that the hard disc on their computer is corrupted and they do not have another copy of an assignment that is due that day. Physical symptoms include dry mouth, palpitations, appetite changes and insomnia, while psychological responses can include anxiety and forgetfulness and, in extreme circumstances, burnout or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Physiologists in the first half of the 20th century such as Cannon and Selye were the first researchers to describe the stress response and pioneered research in this field.

FIGHT OR FLIGHT

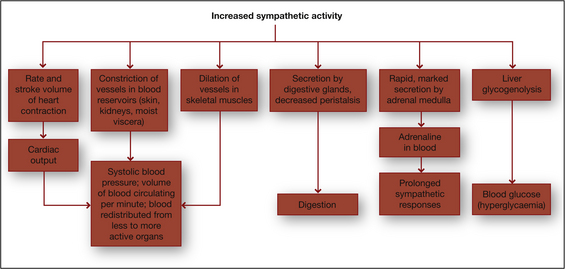

Walter Cannon (1932) was a physiologist and early stress researcher who first described the fight or flight response – a primitive inborn protective mechanism to defend the organism against harm. The response is a physical reaction by an organism (including humans) to a perception of threat. Cannon observed that when an organism was threatened the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system were aroused preparing the organism to respond to the anticipated danger by either reacting aggressively (fight) or by fleeing (flight).

The physiological mechanism of this involves arousal of the sympathetic nervous system that stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) which then elevate blood pressure, increase the heart rate, divert blood supply from internal organs to muscles and limbs and dilate pupils to enable the organism to take action in the face of a threat (see Fig 10.1). Activation of the endocrine system prompts the secretion of cortisol by the adrenal glands that provides a quick burst of energy, heightened alertness and memory and increases the organism’s pain threshold. Together they enable the organism to confront or withdraw from the threat.

In the landmark Whitehall I and II studies, British civil servants in lower level jobs experienced greater stress due to having less control of their workload than higher level employees (Marmot et al 1997). Further, the final report of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Commission of Social Determinants of Health states that ‘stress at work is associated with a 50% excess risk of coronary heart disease and there is consistent evidence that high job demand, low control and effort–reward imbalance are risk factors for mental and physical health problems (WHO 2008 p 8).

Research focus

Marmot M, Kogevinas M, Elston M 1987 Social economic status and disease. Annual Review of Public Health Vol 8, pp 111–135

Whitehall I and II

Whitehall II followed up on the findings of Whitehall I with a prospective cohort study of over 10,000 men and women, aged 35–55 years, employed in the British civil service between 1985 and 1998 with the purpose of identifying the relationship between occupational and psychosocial factors in the workplace and risk for coronary heart disease for both men and women. The researchers concluded that ‘low control in the work environment is associated with an increased risk of future coronary heart disease among men and women employed in government offices’ (Bosma et al 1997 p 558).

GENERAL ADAPTATION SYNDROME (GAS)

Hans Selye (1956) was another pioneer stress researcher who identified the relationship between stress and illness in a model he called the general adaptation syndrome (GAS). The GAS provides a biomedical explanation of the stress response and how it influences health outcomes. The theory identifies a pattern of reaction to a threat or challenge and proposes that stress is the individual’s non-specific response to the specific environmental stressor. Selye defined this as a demand on the body that induces the stress response; that is, the individual is required to adapt (Selye 1956). GAS is non-specific in that the response is the same regardless of stimuli; that is, whether the stressor is physical or emotional or whether it is viewed as positive or negative.

The GAS includes three phases:

Despite the influence of Seyle’s stress response model on stress research it does not escape criticism. Namely, that it describes a physiological process and overlooks the role of cognitive appraisal as identified by Lazarus and Folkman (1984); second, not all individuals respond in the same physiological way to stress; and third, Selye’s model refers to responses to actual stress whereas an individual can experience the stress response to an anticipated stressor (Taylor 2009 p 148). For example, in agoraphobia the person fears the anxiety they might experience if they leave their ‘safe place’.

CRITICAL THINKING

Imagine you are driving from your home in the hills to your university to sit a health psychology exam when a cat suddenly darts in front of your car. You brake quickly, swerve and, fortunately, avoid hitting it. You are not injured but your car came to a halt against a fence post and sustained significant damage to the front end. Water is now leaking from the damaged radiator. When you try to call for assistance you discover your mobile phone is out of range. The road is quiet and traffic infrequent. You know that the nearest house is about five kilometres further on. Consider:

Imagine you are driving from your home in the hills to your university to sit a health psychology exam when a cat suddenly darts in front of your car. You brake quickly, swerve and, fortunately, avoid hitting it. You are not injured but your car came to a halt against a fence post and sustained significant damage to the front end. Water is now leaking from the damaged radiator. When you try to call for assistance you discover your mobile phone is out of range. The road is quiet and traffic infrequent. You know that the nearest house is about five kilometres further on. Consider:In summary, the stress response is an automatic reaction that enables the individual to take action in order to adapt to, or make changes in response to, a perceived or actual threat or stressor. The stress response is most effective for stressors that are of short-term duration and where adaptation is possible. However, should adaptation not be achievable or the stress prolonged the individual is at risk of developing health problems as a consequence.

Stress as a stimulus

Another approach to stress research is to view it as a stimulus that produces a reaction. According to Yerkes and Dodson (1908) stress is the stimulus that prompts action and the amount of stress experienced predicts how well the individual performs The stimulus can be a major life event such as those as identified by Holmes and Rahe in 1967 (see Table 7.4). Alternatively the stimulus may be an accumulation of minor life events or hassles as described by Kanner and colleagues in a study that compared the stress from daily hassles and uplifts with the stress produced by major life events (Kanner et al 1981).

YERKES–DODSON LAW

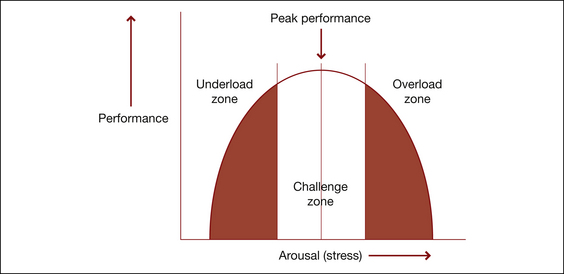

Yerkes and Dodson (1908) hypothesised that a relationship exists between arousal and performance and that stress is a stimulus that prompts the individual to take action. According to the Yerkes–Dodson law, when stressed (aroused) the individual’s performance increases to a maximum point after which performance reduces. The relationship is represented graphically as an inverted ‘U’ (see Fig 10.2).

The model proposes that there is an optimal level of arousal (stress) at which the individual is challenged and thereby performs at their best. With too little arousal the individual is not sufficiently motivated to take action in response to the stimulus and hence performance is minimal. Increasing arousal energises the individual to take the action required to achieve a goal such as study to pass an exam. However, excessive arousal can result in the individual being overloaded and, consequently, performance deteriorates such as the student who is highly anxious about a forthcoming exam and loses concentration or becomes ill.

Major life events

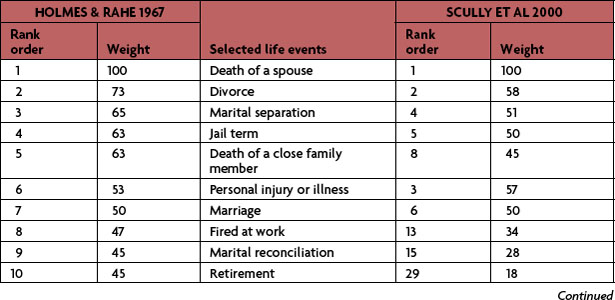

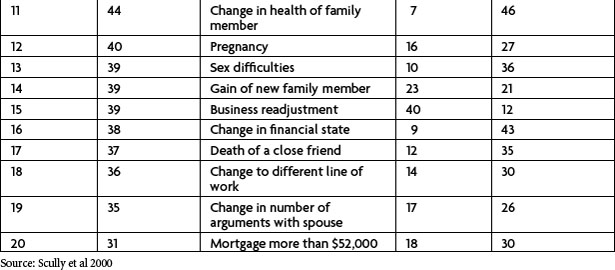

Items in the SRRS are given a weighting that reflects the magnitude of the stressful stimulus (see Table 10.2). For example, the death of a spouse was found to be the most stressful life event and was given a score of 100. A score of 150–299 for the preceding year places the individual at moderate risk for illness, whereas a score of 300 in the preceding six months or more than 500 in the preceding year places the individual at high risk of developing a stress-related illness.

Since its development in the 1960s the Holmes–Rahe SRRS is one of the most widely cited tools in the stress research. Thirty years later Scully and colleagues replicated the research to examine the usefulness of the tool as an indicator of health risk and to consider the validity of criticisms raised in the literature in relation to the tool. Scully et al’s research found that the relative weightings and rank order of the selected life events remained valid and concluded that SRRS continues to be ‘a robust instrument for identifying the potential for the occurrences of stress-related outcomes (Scully et al 2000 p 875). Table 10.2 compares weight and rank order for selected stressors in Holmes and Rahe’s seminal study and the replication by Scully et al.

Minor life events

In summary, it is evident that both major and minor events may stimulate a stress reaction in humans that, in turn, can impact health. Nevertheless, the presence of a stressful stimulus is not predictive of how an individual will respond to the stressor. Different people will respond differently to the same stressor and the same event can lead to positive or negative outcomes in different individuals. This observation prompted psychologists studying stress to examine the relationship between the individual and their environment, that is, stress as a process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree