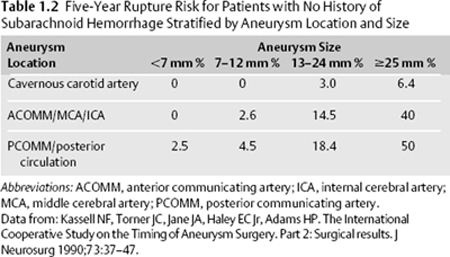

1 Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Harshpal Singh, Joshua B. Bederson, and Jennifer A. Frontera Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is defined as the presence of blood within the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid membrane and the pia mater. SAH may be categorized as traumatic or nontraumatic. Nontraumatic or spontaneous SAH accounts for 1 to 7% of all strokes; ~80 to 90% of the time they can be attributed to the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. Approximately 5% of the population harbors an intracranial aneurysm, and 20 to 30% of this population will have multiple aneurysms.1 However, the vast majority of aneurysms never rupture. The annual incidence of spontaneous SAH is 2 to 25 per 100,000 people, and ~30,000 spontaneous SAHs occur in the United States per year.2 The peak age range for aneurysmal SAH is 50 to 60 years, and it is more common in women and blacks. Although it is unclear why, aneurysmal SAH occurs more commonly in the winter and spring (Table 1.1). Previous SAH is one of the strongest predictors of SAH. Patients with previously ruptured aneurysms should undergo repair of additional unruptured aneurysms. The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA)3 addressed treatment of unruptured aneurysms detected in patients with and without previous SAH. In patients without a history of SAH, patients >50 years of age with large posterior circulation aneurysms are at the greatest risk for both rupture and repair complications (Table 1.2). The decision whether to treat an unruptured aneurysm should involve a discussion of the risks of rupture and the risks and benefits associated with treatment. Considerations include aneurysm size and location, as well as the patient’s age and comorbidities. Often, patients without a history of SAH and with aneurysms <7 mm are observed and followed with serial imaging.

| Modifiable Risk Factors | Nonmodifiable Risk Factors |

| Cigarette smoking (dose-dependent effect on aneurysm formation; the most important modifiable risk factor) | Previous SAH (new aneurysm formation rate 1–2% per year) |

| Hypertension | Polycystic kidney disease |

| Moderate to heavy EtOH use | Connective tissue disease (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome) |

| Cocaine use | Aortic coarctation |

| Endocarditis (mycotic aneurysm) | Pseudoxanthoma elasticum Moyamoya disease Arteriovenous malformation Fibromuscular dysplasia Dissection with pseudoaneurysm Vasculitis Neurofibromatosis 1 Glucocorticoid remediable hyperaldosteronism Family history (Japanese and Finnish cohorts. Familial intracranial aneurysm syndrome: Two 1st- to 3rd-degree relatives with intracranial aneurysms; 8% risk of having an unruptured aneurysm. These patients tend to have SAH at a younger age and have multiple aneurysms.) |

Abbreviations: EtOH, ethyl alcohol; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

History and Examination

History

The most common presenting complaint is that of a severe headache. Often patients present with a warning or “sentinel” headache that precedes the “thunderclap” headache. Some patients complain of pain radiating down the legs; this is due to pooling of blood in the lumbar cistern and the irritation of nerve roots. Neck stiffness, photophobia, and meningeal symptoms occur. Diplopia (due to cranial nerve palsy) is also common. Loss of consciousness at ictus can occur due to a sudden rise in intracranial pressure (ICP) with a consequent drop in cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). This should be distinguished from seizure.

Twelve percent of those with SAH die before reaching medical attention. The misdiagnosis of SAH is thought to be as high as 12% (particularly in patients with mild symptoms).4 Because treatment is urgent and the consequences of misdiagnosis are severe, a high index of suspicion for SAH should be maintained.

Physical Examination

Kernig’s or Brudzinski’s sign may signify meningismus from SAH. Assess for external signs of trauma to evaluate for traumatic versus spontaneous SAH.

Neurologic Examination

- A full neurologic examination, including assessment of mental status, cranial nerves, motor skills, and reflexes, as well as a sensory and cerebellar examination, should be performed on all patients.

- Cranial nerve III compression classically occurs from an aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery, but it can also occur with posterior cerebral artery or superior cerebellar artery aneurysms. Uncal herniation causing pupillary dilatation, third nerve palsy, and deteriorating mental status is an ominous sign. Lateral rectus (6th nerve) palsy may signify an increased ICP, but it is generally nonlocalizing.

- Retinal examination: subhyaloid hemorrhages occur in 13% of SAH patients (Terson syndrome).5

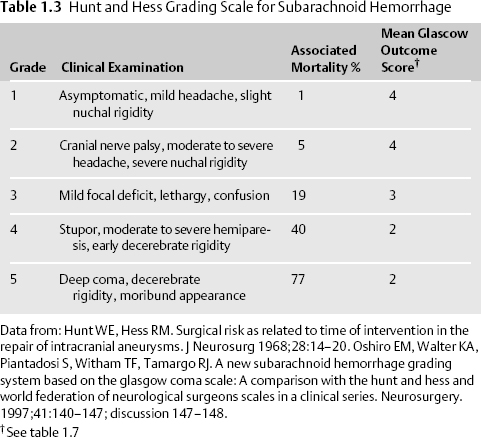

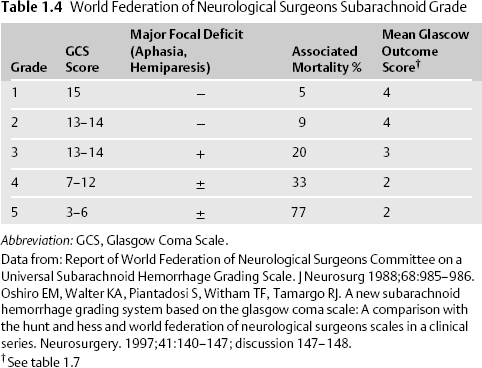

- The Hunt and Hess6 and the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) clinical grading scales for SAH are commonly employed. (Table 1.3, Table 1.4).

Differential Diagnosis

- Ruptured saccular cerebral aneurysm. Ninety percent of aneurysms develop in the anterior circulation, most commonly the anterior communicating artery (ACOMM, 30%), the posterior communicating artery (PCOMM, 25%), the middle cerebral artery (MCA) bifurcation (20%), the internal carotid artery (ICA) bifurcation (8%), and 7% from other locations. Ten percent of aneurysms arise from the posterior circulation.

- Traumatic SAH. Typically convexity SAH, often accompanied by a clear history of trauma and other signs of injury such as orbital frontal contusions, skull fracture, or external scalp trauma.

- Vascular malformation

- Arteriovenous malformation (AVM). AVMs are congenital malformations comprised of direct fistulas from arteries to veins without any intervening capillary bed. The interposed brain tissue is nonfunctional. Patients may present with SAH, intracerebral hemorrhage, intraventricular hemorrhage, seizures, headache, or neurologic deficits. The bleeding rate of an AVM is 2 to 4% per year, and the recurrent bleeding rate is 6 to 18% per year (highest during the first year after an initial bleed).7,8,9 The lifetime risk of hemorrhage is 105 minus the patient’s age (in years).10 Risk factors for rupture include previous rupture, high pressure over the malformation, small nidus, deep brain location, intranidal or feeding artery aneurysms, deep venous drainage, and venous occlusions. Patients with no risk factors have a bleeding rate as low as 0.9% annually.11 Repair options include embolization with subsequent resection or gamma knife obliteration (for lesions <3 cm). The Spetzler-Martin AVM grading scale assesses surgical risk.12 Grading is based on size, location, and venous drainage pattern: <3 cm = 1 point, 3 to 6 cm = 2 points, >6 cm = 3 points; eloquent location = 1 point, noneloquent location = 0 point; deep venous drainage = 1 point, superficial venous drainage = 0 point. Increasing points correlate with a higher surgical risk for resection.

- Cavernous malformations are vascular lesions with closely spaced sinusoidal vessels lacking a smooth muscle layer and without interspaced neural tissue. They appear as “popcorn-like” lesions on gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with differing ages of blood products. The annual bleeding rate is 0.25 to 1.1% in the anterior circulation with a rebleed rate of 4.5% per year.13 The annual bleeding rate for posterior fossa cavernous malformations is 2 to 3% with a 17 to 21% rebleed rate.14 The high rate of rebleeding for posterior fossa lesions may be related to a higher likelihood of symptoms from small bleeds in very eloquent tissue. Cavernous malformations are angiographically occult, but they may be associated with developmental venous anomalies.

- Intracranial dissection with pseudoaneurysm rupture

- Vasculopathy-related SAH. Vasculopathy may present with multiple strokes, cognitive changes, psychiatric symptoms, seizure, headache, and rarely SAH. Etiologies include primary central nervous system (CNS) angiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, lupus, cryoglobulinemia, Kawasaki disease, bacterial meningitis, viral infections (hepatitis B and C, cytomegalovirus [CMV], Epstein-Barr virus [EBV], parvovirus B19, varicella, and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), syphilis, CNS tuberculosis, drug-induced vasculopathy (e.g. SSRI), and cocaine- and methamphetamine-induced vasculopathy.

- Oncotic aneurysm rupture

- Endocarditis with mycotic aneurysm rupture (typically distal fusiform artery aneurysms; may be accompanied by vasculitis).

- Meningitis/encephalitis. Can be mistaken for SAH with symptoms of headache and meningeal findings. Look for fever, lumbar puncture results.

- Thunderclap headache and benign coital headache

- Vascular malformation

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

- Aneurysmal SAH

- Dissection with pseudoaneurysm rupture

- Endocarditis with mycotic aneurysm rupture

- Meningitis/encephalitis

Diagnostic Evaluation

- Imaging studies.

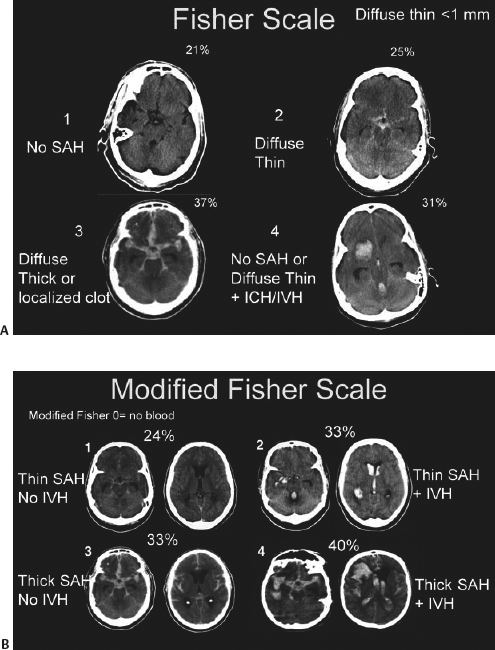

- Noncontrast CT scan. SAH is radiographically visible in 90% of patients within 24 hours of ictus, but the sensitivity of CT drops to 60% 5 days after ictus.15 The thickness of SAH clot and the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) both predict the risk of vasospasm. The modified Fisher scale incorporates the risk of vasospasm due to both SAH and IVH into its grading system (Table 1.5, Fig. 1.1).16,17,18

- Cerebral angiogram. Gold standard for ruling out a ruptured cerebral aneurysm, for defining the relevant neuroanatomy, and possibly providing immediate endovascular treatment. Fifteen to 20% of SAH patients have negative angiograms. Repeat angiography detects an abnormality in 1 to 2%.19

- CT angiography (CTA). >5 mm aneurysm = 95 to 100% sensitive, <5 mm aneurysm = 64 to 83% sensitive.20,21

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). >5 mm aneurysm = 85 to 100% sensitive, <5 mm aneurysm = 56% sensitive.22

- Cerebral angiogram. Gold standard for ruling out a ruptured cerebral aneurysm, for defining the relevant neuroanatomy, and possibly providing immediate endovascular treatment. Fifteen to 20% of SAH patients have negative angiograms. Repeat angiography detects an abnormality in 1 to 2%.19

- Noncontrast CT scan. SAH is radiographically visible in 90% of patients within 24 hours of ictus, but the sensitivity of CT drops to 60% 5 days after ictus.15 The thickness of SAH clot and the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) both predict the risk of vasospasm. The modified Fisher scale incorporates the risk of vasospasm due to both SAH and IVH into its grading system (Table 1.5, Fig. 1.1).16,17,18

- Lumbar puncture. A lumbar puncture must be performed if the history is suspicious for SAH and the head CT is negative. Always check an opening pressure. Look for clearing of blood between tubes 1 and 4 and spin for xanthochromia (may not be present within 12 hours of ictus, but it remains for ~2 weeks).

- Laboratory studies. Perform toxicology screen in at-risk populations.

- See 2009 AHA/ASA guidelines on pages 337–340 for the management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (Addendum).23

- Laboratory studies. Perform toxicology screen in at-risk populations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree