Percentage of subjects with clinically significant cognitive complaints based on the BC-CCI.

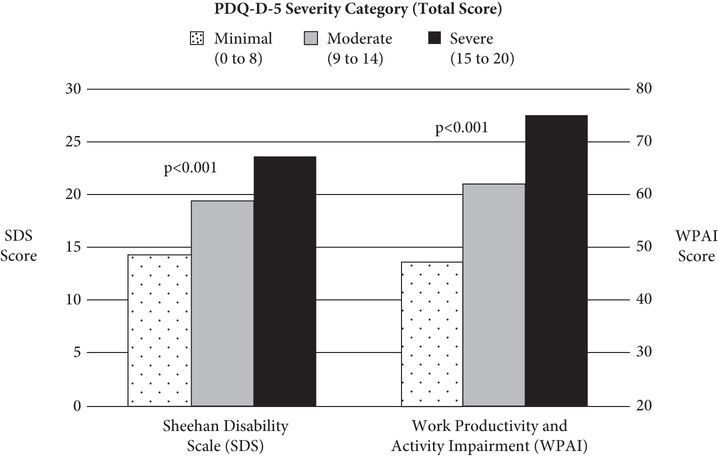

Cognitive symptoms also clearly affect psychosocial functioning. Sad mood and concentration difficulties were found on multivariate analysis to be the depressive symptoms that had the highest unique associations with impairment in multiple domains of psychosocial functioning (Fried & Nesse, 2014). A survey of 164 employed depressed patients attending a mood disorders clinic found that 52 percent reported that cognitive symptoms were highly impairing of work functioning (Lam et al., 2012). Another naturalistic study of 947 patients with MDD evaluated functional outcomes using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS, Leon, Olfson, Portera, Farber, & Sheehan, 1997) and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI, Reilly, Zbrozek, & Dukes, 1993) scale, and evaluated cognition using a brief self-rated questionnaire, the five-item version of the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ, Sullivan, Edgley, & Dehoux, 1990). Higher scores on the PDQ, indicating greater subjective cognitive dysfunction, were associated with greater functional impairment as assessed by both the SDS and the WPAI (Figure 17.2) (Saragoussi et al., 2013).

Functional impairment (as measured by SDS and WPAI scores) increases with greater self-perceived cognitive dysfunction (as measured by PDQ-D-5 Severity Category).

Cognitive symptoms are also one of the most common residual symptoms for patients during treatment for MDD. In the large US Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, frequency of residual symptoms was examined in 428 patients who had a clinical response (at least 50 percent improvement in depression scores) but were not in symptom remission after 12 weeks of treatment with citalopram 20–60 mg/day (McClintock et al., 2011). Persistent problems with concentration and decision-making were experienced by 71 percent of these patients. In another study of 117 patients who were in full or partial remission after three months of antidepressant treatment, cognitive symptoms were reported by more than 30 percent of patients and were associated with overall severity of residual depressive symptoms (Fava et al., 2006).

Given the clinical impact of cognitive symptoms for both diagnosis and management, it is important to properly assess cognition in patients with MDD. There is increasing focus in depression management on measurement-based care – the systematic use of validated outcome assessments to guide and monitor treatment decisions (Trivedi, 2013). Studies have shown that measurement-based care for depression can improve patient outcomes compared with treatment as usual (Yeung et al., 2012). Assessment of cognitive dysfunction should be integrated into measurement-based care, especially since its response to treatment may be independent of other depressive symptoms.

Neuropsychological tests are usually considered the “gold standard” for assessing cognitive dysfunction. Unfortunately, neuropsychological assessment is impractical for use in routine clinical care because it requires specific expertise and is not widely accessible to patients or clinicians. Brief clinician-administered cognitive tests, such as the Mini Mental State Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), were designed to screen for cognitive impairment in dementia and similar disorders and are not sensitive enough to detect the more subtle cognitive deficits found in MDD. Similarly, commonly used depression rating scales, whether clinician-rated (e.g. the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale or the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale) or patient-rated (e.g. the Patient Health Questionnaire), usually have only a single item dealing with cognitive symptoms and may not adequately address important cognitive domains. Hence, a patient-rated cognitive assessment scale may enhance the comprehensive evaluation of cognition beyond the standard clinician interview (Schwartz, Kozora, & Zeng, 1996). In busy clinical settings, self-rated scales are also more feasible for measurement-based care than clinician-administered scales or formal neuropsychological testing.

Subjective versus objective assessment of cognitive function

There is considerable evidence that subjective measures of cognition are not well correlated with objective findings on neuropsychological tests (Trepanier & Nolin, 1997; Schmidt, Berg, & Deelman, 2001; Lovera et al., 2006). This has been demonstrated in most neurological and psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia (Tomida et al., 2010) and bipolar disorder (Burdick, Endick, & Goldberg, 2005; Van der Werf-Eldering et al., 2011). Similarly, there are several studies involving patients with MDD showing low correlations between subjective and objective measures of cognitive dysfunction (Lahr, Beblo, & Hartie, 2007; Mowla et al., 2008; Huang, 2010; Svendsen, Kessing, Munkholm, Vinberg, & Miskowiak, 2012). Patients’ self-ratings of cognitive difficulty are also usually higher than ratings from family observers (Lahr et al., 2007).

In contrast, many studies have shown moderate but significant correlations between scores on subjective cognitive assessment scales and depression symptom rating scales (Biringer et al., 2005, 2007; Stenfors, Marklund, Magnusson Hanson, Theorell, & Nilsson, 2014; Olsen et al., 2015). This suggests that self-perception of cognition may be associated with depressive symptom severity. For example, self-assessment of cognition in people with depression may be subject to cognitive distortions, such as catastrophizing small decrements in memory performance. This might explain why their subjective assessment of memory and thinking is worse than their objective performance on neuropsychological tests.

However, an alternative explanation is that subjective and objective cognitive assessments may be measuring different aspects of cognition. Neuropsychological tests, by definition, are “snapshot” assessments at a single point in time. They are usually conducted in a controlled testing environment with minimal stress and distractions. Thus, performance on neuropsychological tests may not be generalizable to longer periods of time or to stressful situations such as the workplace, where cognitive dysfunction may be worse than in a testing situation. In contrast, a person completing a subjective scale is assessing their cognitive difficulties over an extended period of time (days or weeks) and over a number of different situations. Subjective scales can also assess a perceived change from the usual baseline for a particular person, while objective tests cannot (unless a premorbid baseline test was done).

Emerging evidence also suggests that changes in subjective assessment of cognition may have stronger correlations to changes in neuropsychological tests (Zimprich, Martin, & Kliegel, 2003). In a study examining cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis, there were no significant correlations between scores on a self-rated cognitive scale (the five-item version of the PDQ, or PDQ-5) and composite z-scores based on neuropsychological testing (a modified version of the Brief Repeatable Battery), either at baseline or after 24 weeks of treatment (Christodoulou et al., 2005). However, the change in PDQ-5 score between baseline and post-treatment was significantly correlated to change in neuropsychological performance. This finding has been replicated in a secondary analysis of data from an eight-week, placebo-controlled clinical trial in patients with MDD treated with vortioxetine (McIntyre, Lophaven, & Olsen, 2014). We found that the change in score from baseline to eight weeks on the 20-item version of the PDQ was significantly correlated with the composite z-score of several neuropsychological tests (Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making Test, Stroop, Simple Reaction Time task, Choice Reaction Time task) (Olsen et al., 2015). These findings suggest that, while patients may not accurately self-assess their objective cognitive performance relative to their normal functioning or to others, they may be better able to self-assess changes in their own objective cognitive functioning over time. Hence, subjective cognitive scales may be clinically useful, even without objective testing, to monitor changes in cognition with treatment.

In summary, neuropsychological assessment has many limitations for routine clinical use whereas subjective cognitive assessments may have greater relevance to real-world situations. Self-rated cognitive scales may also assess different aspects of cognition than neuropsychological tests. Although patients may not accurately self-assess their neuropsychological performance at a given time point, their responses on subjective cognitive scales may accurately detect changes in their neuropsychological performance. A comprehensive evaluation of cognitive dysfunction in an individual patient may require both objective and subjective cognitive assessment.

Cognitive assessment scales in depression

A number of self-assessment tools have been developed to assess cognition and cognitive dysfunction. Selection of a particular cognitive scale will depend on a number of factors, including psychometrics, reason for use, patient population, and setting.

Any cognitive scale must demonstrate adequate psychometric properties, including consistency, validity, and reliability. From a psychometric perspective, the greater the number of items on a scale, the higher the accuracy of measurement. From a clinical perspective, the fewer the number of items, the lower the burden for respondents. The purpose and context of the assessment will thus affect the type of scale to be used. In research settings, more detailed and longer assessments are often necessary to assess individual domains of cognition. In clinical trial settings, scales must demonstrate sensitivity to change and ability to detect clinically important differences between treatments. In busy clinical settings, scales must be brief, acceptable to patients and clinicians, and easy to administer. Language and readability are also important considerations in settings where patients have varied educational, social, and cultural backgrounds.

Scales must also be appropriate for the target population. There are many scales for cognitive assessment, but most were designed for use as a screening or monitoring tool for dementia or for elderly populations. Few have been validated in MDD populations. A literature search for published papers up to October, 2014, found only three cognitive scales that have been psychometrically validated specifically in adults with MDD (Table 17.1). These are described in greater detail in the following sections.

Subjective cognitive scales that are psychometrically validated in major depressive disorder

| Validation citation | Scale | Number of items | Validation samples | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iverson & Lam, 2013 | BC-CCI | 6 | MDD = 62; Healthy = 112 |

|

| CPFQ | 7 | MDD = 150; MDD = 50 GAD = 381 MDD = 495; MDD = 227 MDD = 483 MDD = 776 |

| |

| Lam et al., 2013 | PDQ-D PDQ-D-5 | 20 5 | MDD = 421 Healthy = 434 |

|

British Columbia Cognitive Complaints Inventory (BC-CCI)

The British Columbia Cognitive Complaints Inventory (BC-CCI) is a six-item scale designed to assess perceived problems with concentration, memory, trouble expressing thoughts, word finding, slow thinking, and difficulty solving problems (Table 17.1; Appendix 17.1) (Iverson, 2007). Each item is rated on a four-point scale: 0 = not at all, 1 = some, 2 = quite a bit, and 3 = very much. The time period for recall is the past seven days. Total scores range from 0 to 18; the higher the score, the greater the severity of cognitive complaints. The BC-CCI was validated in a convenience sample of 62 patients with MDD and 112 non-depressed community volunteers (Iverson & Lam, 2013). The internal consistency of the BC-CCI was good for both patient (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86) and community (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82) samples. A principal components analysis found two factors in the depressed sample: a cognitive factor (concentration, forgetfulness, problem-solving, slow thinking) and an expressive language factor (expressing thoughts, word finding). Only one factor was extracted in the community sample. As a measure of convergent validity, the BC-CCI scores were compared for each severity category on the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). There was also a moderate, significant correlation of the BC-CCI score to the BDI-II score in both patient (r = 0.66, p < 0.01) and community volunteer (r = 0.43, p < 0.01) samples.

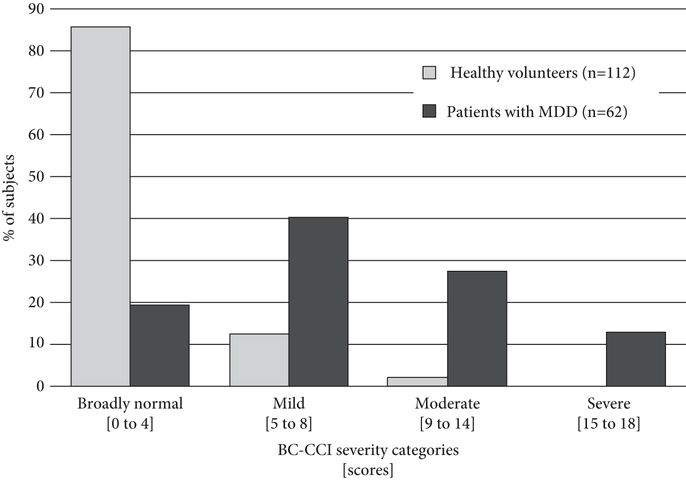

Based on frequency distributions, four classification groups and scoring ranges were identified: broadly normal (0 to 4), mild cognitive complaints (5 to 8), moderate cognitive complaints (9 to 14), and severe cognitive complaints (15 to 18). Figure 17.3 shows the percentage of patients compared to community volunteers in each of these severity categories. Over 40% of the depressed sample had moderate or severe cognitive complaints compared to less than 2% of the healthy volunteers.

Percentage of subjects in each severity category on the BC-CCI.

In summary, the BC-CCI is a brief, simple questionnaire with good internal consistency and face validity in a sample of depressed patients and non-depressed community volunteers. It has not yet been evaluated for responsivity or sensitivity to change, or validated against other cognitive measures, whether subjective or objective.

Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ)

The Massachusetts General Hospital Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ, Fava, Iosifescu, Pedrelli, & Baer, 2009) is composed of seven items chosen by “clinical experience” of the investigators (Table 17.1). The seven items include motivation/interest/enthusiasm, wakefulness/alertness, energy, ability to focus/sustain attention, ability to remember/recall information, ability to find words, and sharpness/mental acuity (Appendix 17.2). The recall period for respondents is the past month. Each item is rated on a six-point scale: 1 = greater than normal, 2 = normal, 3 = minimally diminished, 4 = moderately diminished, 5 = markedly diminished, and 6 = totally absent. Total scores range from 7 (greater than normal) to 36 (severe); the higher the score, the greater the severity of cognitive symptoms.

The CPFQ underwent an initial series of validation studies using data from samples of patients evaluated for other studies (Fava et al., 2009). In a convenience sample of 150 patients with MDD who were in full or partial symptom remission following medication treatment, the CPFQ showed good internal consistency for the total score (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) and a factor analysis using principal components analysis found a single-factor model. In a second sample of 50 patients with MDD who had inadequate response and residual cognitive complaints, the CPFQ also showed good test–retest reliability (mean of eight days between testing, r = 0.83, p < 0.001).

Convergent validity was assessed in these samples by comparing CPFQ scores with a number of other self-rated assessments. The CPFQ score was significantly correlated in the first sample with measures of sleepiness and fatigue, and in the second sample to measures of amotivation and apathy. In 33 subjects from the second sample, changes from baseline to post-treatment in the CPFQ scores were compared with changes in the Conners Continuous Performance Test (CPT) (Conners, 1985), a neuropsychological test that assesses sustained and selective attention with accuracy evaluated by errors of commission (false response to an incorrect stimulus) and omission (lack of response to a correct stimulus). The CPFQ scores were significantly correlated to errors of commission on the CPT (r = 0.33, p < 0.05), but not to errors of omission. Finally, the baseline CPFQ scores also showed moderate, significant correlations to the 31-item HAM-D scores (r = 0.32, p = 0.02).

Further validation of the CPFQ was conducted using pooled data from four independent clinical trials (with sample sizes ranging from 227 to 776 participants) of antidepressants for patients with MDD, including three that were placebo-controlled studies (Baer et al., 2014). Many of the results replicated the findings in the previous validation. However, in these studies, the factor analysis revealed a two-factor structure (one of fatigue/apathy, and the other of cognition), although each subscale appeared to function similarly to the total score. The CPFQ also demonstrated good sensitivity to change, with significantly higher scores in the antidepressant-treated groups compared with placebo in two of the three placebo-controlled trials.

In summary, the CPFQ is a brief, well-validated questionnaire for patients with MDD. The strengths include a correlation with a neuropsychological test (the CPT) and the demonstration of sensitivity to change within large clinical trials of MDD. The limitations are the unusual anchor points (with greater than normal as a possible response) and scoring (with “normal” having a score of 7), since greater than normal functioning on some items can impact the total score for impairment. The CPFQ may be particularly useful when assessments of both subjective fatigue and cognition are desired.

Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ)

The Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (Sullivan et al., 1990) is a self-report scale initially developed to assess cognitive dysfunction as a component of a Quality of Life battery for patients with multiple sclerosis (Fischer et al., 1999). The PDQ (Table 17.1) is composed of 20 items with five items each contributing to four subscales: attention/concentration, retrospective memory, prospective memory, and planning/organization. The period of recall was the past four weeks. Each item is scored on a five-point scale: 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = almost always. Total score ranges from 0 to 80; higher scores indicate greater perceived cognitive impairment.

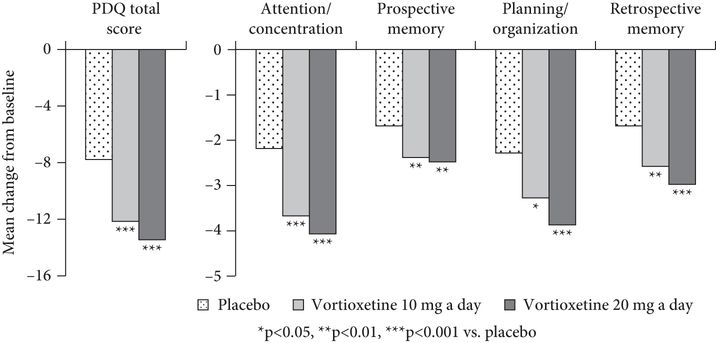

The PDQ was included in a multicenter, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial examining the cognitive effects of vortioxetine, a novel antidepressant with a multimodal mechanism of action (McIntyre et al., 2014). Patients with MDD (n = 602) were randomized 1:1:1 to vortioxetine 10 mg/day or 20 mg/day or placebo and treated for eight weeks. Compared with placebo, both of the vortioxetine groups had significantly greater improvement in depression scores between baseline and post-treatment. Both vortioxetine groups also showed significantly greater improvement on the PDQ than the placebo group, demonstrating good sensitivity to change (Figure 17.4).

Mean change from baseline to week 8 in PDQ total score and PDQ subscale scores.

The PDQ was recently adapted for use in patients with MDD. For the PDQ – Depression (PDQ-D), the recall period was changed to seven days and some of the questions modified to be more relevant to patients with depression (Appendix 17.3). In a qualitative study, focus groups of patients with depression found that the PDQ-D was easy to understand and relevant to patient experiences of cognitive symptoms (Fehnel et al., 2013). We have recently conducted validation studies for the PDQ-D in an online study with depressed (n = 421) and non-depressed (n = 434) subjects (Lam et al., 2013). The internal consistency of the PDQ-D was very good for the overall score (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95) and for each of the four subscales (Cronbach’s alpha from 0.81 to 0.89). Convergent validity was established with significant correlations of PDQ-D scores with other cognitive scales. Higher scores on the PDQ-D were associated with poorer psychosocial outcomes including work functioning and health-related quality of life measures. For example, the PDQ-D score was moderately correlated with the SDS score (r = 0.32 to 0.53, p < 0.001). A subset of depressed respondents (n = 190) were reassessed after six weeks. The PDQ-D showed responsivity to change in this sample, in that PDQ-D scores were significantly reduced in patients with improvement in depression severity, and significantly increased in those showing worsening of depression. A confirmatory factor analysis supported the scoring of a single overall score for perceived cognitive impairment.

Given the support for a single global PDQ-D score, a five-item screening version (PDQ-D-5) has also been proposed (Appendix 17.4) and a psychometric validation study in MDD is in progress. The PDQ-D-5 should be useful in clinical settings as a brief screening and monitoring tool for cognitive dysfunction. We have developed a free website (optimized for mobile devices) for the general public, www.MoodFx.ca, which is designed to support measurement-based care with self-rated tools. MoodFx (pronounced Mood Effects) incorporates the PDQ-D-5 along with other brief, validated symptom and functional rating scales to screen and monitor outcomes during depression treatment.

In summary, the PDQ-D is an extensively validated cognitive scale that shows good psychometric properties and responsivity to change in both online depressed subject samples and in patients with MDD in clinical trials. The 20-item version provides a comprehensive assessment of subjective cognitive dysfunction in four major domains, and a brief five-item screening version is available for clinical settings.

Other cognitive assessment scales

There are many other cognitive scales available, but most have only been used in general population or elderly samples or for screening for dementia, and have not yet been validated in patients with MDD. Some examples include the Cognitive Dysfunction Questionnaire (CDQ), which has been validated in a general population sample (Vestergren, Ronnlund, Nyberg, & Nilsson, 2011), the Medical Outcomes Study Cognitive Functioning Scale (MOS-Cog), which has been used in studies of bipolar disorder (Kaye, Graham, Roberts, Thompson, & Nanry, 2007), and the Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ), which attempts to assess both prospective and retrospective episodic memory (Crawford, Smith, Maylor, Della Sala, & Logie, 2003).

Another interesting cognitive scale, the Applied Cognition-General Concerns (ACGC) Scale, is available in the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (Cella et al., 2010). PROMIS is an initiative of several research centers and funded by the US National Institutes of Health to provide highly reliable and valid assessments of patient-reported health, including physical, mental, and social well-being. Scales are standardized and comparisons available across many different chronic health conditions, including depression. The ACGC is a self-report assessment of cognition consisting of 34 items in the full item bank, although shorter versions with four, six, and eight items are available. An advantage of using the ACGC and the PROMIS scales is the potential use of computerized adaptive testing (CAT), in which successive items are presented only if needed to derive a valid score. A person with minimal symptoms or severity would answer only a minimum number of items, while someone with more severe symptoms would have additional questions presented, thereby ensuring full validity and precision of scores across the entire severity spectrum (Pilkonis et al., 2014). However, in a qualitative study the PDQ-D was preferred over the ACGC by people with depression (Fehnel et al., 2013).

Summary and conclusions

Subjective cognitive complaints are a hallmark of MDD and are important enough to warrant careful clinical evaluation. The limited correlation between subjective cognitive scales and objective neuropsychological tests suggests that they measure different aspects of cognition. Self-assessment of cognition may be confounded by depressive severity and depression-related cognitive bias but may also be more reflective of real-world cognitive functioning than a battery of neuropsychological tests. It is also possible that subjective cognitive assessment may be better correlated to objective measures of “hot cognition,” or emotion-dependent cognitive processes (see Chapter 6 in this volume) than to those of traditional neuropsychological tests that primarily assess “cold cognition.” This will be an important research question to answer.

Many studies have also shown that subjective cognitive symptoms and neuropsychological deficits in MDD may continue as residual symptoms in patients with partial response to treatment and may persist even when patients are otherwise regarded as being in symptom remission. It is therefore important to monitor cognitive functioning during treatment of MDD to ensure that cognition returns to normal and that psychosocial functioning is restored. Currently there are no “gold standard” subjective cognitive scales in MDD, for either research or clinical use. Three scales have been psychometrically validated in MDD populations: the BC-CCI, CPFQ, and the PDQ-D. Only the BC-CCI and PDQ-D have been studied in non-depressed samples and only the CPFQ and PDQ-D have shown responsivity to change in clinical trials. There are still only limited comparisons of any of these scales with objective neuropsychological tests. Regardless, brief, validated subjective cognitive scales are now available which makes it feasible to include assessments of cognition in routine clinical management of depression. However, further studies will need to determine whether the use of these cognitive scales offer advantages in the measurement-based care of patients with MDD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree