Substance Use and Addictive Disorders

20.1 Introduction and Overview

20.1 Introduction and Overview

The most commonly used drugs have been part of human existence for thousands of years. For example, opium has been used for medicinal purposes for at least 3,500 years, references to cannabis (marijuana) as a medicinal can be found in ancient Chinese herbals, wine is mentioned frequently in the Bible, and the natives of the Western Hemisphere smoked tobacco and chewed coca leaves. As new drugs were discovered and new routes of administration developed, new problems related to their use emerged. Substance use disorders are complicated psychiatric conditions and like other psychiatric disorders, both biological factors and environmental circumstances are etiologically significant.

This chapter covers substance dependence and substance abuse with descriptions of the clinical phenomena associated with the use of 11 designated classes of pharmacological agents: alcohol; amphetamines or similarly acting agents; caffeine; cannabis; cocaine; hallucinogens; inhalants; nicotine; opioids; phencyclidine (PCP) or similar agents; and a group that includes sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics. A residual 12th category includes a variety of agents not in the 11 designated classes, such as anabolic steroids and nitrous oxide.

TERMINOLOGY

Various terms have been used over the years to refer to drug abuse. For example, the term dependence has been and is used in one of two ways when discussing substance use disorders. In behavioral dependence, substance-seeking activities and related evidence of pathological use patterns are emphasized, whereas physical dependence refers to the physical (physiological) effects of multiple episodes of substance use. Psychological dependence, also referred to as habituation, is characterized by a continuous or intermittent craving (i.e., intense desire) for the substance to avoid a dysphoric state. Behavioral, physical, and psychological dependence are the hallmark of substance use disorders.

Somewhat related to dependence are the related words addiction and addict. The word addict has acquired a pejorative connotation that ignores the concept of substance abuse as a medical disorder. Addiction has also been trivialized in popular usage, as in the terms TV addiction and money addiction; however, the term still has value. There are common neurochemical and neuroanatomical substrates found among all addictions, whether it is to substances or to gambling, sex, stealing, or eating. These various addictions may have similar effects on the activities of specific reward areas of the brain, such as the ventral tegmental area, the locus ceruleus, and the nucleus accumbens.

Other Terms

Codependence. The terms coaddiction and, more commonly, codependency or codependence are used to designate the behavioral patterns of family members who have been significantly affected by another family member’s substance use or addiction. The terms have been used in various ways and no established criteria for codependence exist.

Enabling. Enabling was one of the first, and more agreed on, characteristics of codependence or coaddiction. Sometimes, family members feel that they have little or no control over the enabling acts. Either because of the social pressures for protecting and supporting family members or because of pathological interdependencies, or both, enabling behavior often resists modification. Other characteristics of codependence include unwillingness to accept the notion of addiction as a disease. The family members continue to behave as if the substance-using behavior were voluntary and willful (if not actually spiteful), and the user cares more for alcohol and drugs than for family members. This results in feelings of anger, rejection, and failure. In addition to those feelings, family members may feel guilty and depressed because addicts, in an effort to deny loss of control over drugs and to shift the focus of concern away from their use, often try to place the responsibility for such use on other family members, who often seem willing to accept some or all of it.

Denial. Family members, as with the substance users themselves, often behave as if the substance use that is causing obvious problems were not really a problem; that is, they engage in denial. The reasons for the unwillingness to accept the obvious vary. Sometimes denial is self-protecting, in that the family members believe that if a drug or alcohol problem exists, then they are responsible.

As with the addicts themselves, codependent family members seem unwilling to accept the notion that outside intervention is needed and, despite repeated failures, continue to believe that greater willpower and greater efforts at control can restore tranquility. When additional efforts at control fail, they often attribute the failure to themselves rather than to the addict or the disease process, and along with failure come feelings of anger, lowered self-esteem, and depression. A summary of some key terms related to substance use disorders is given in Table 20.1-1.

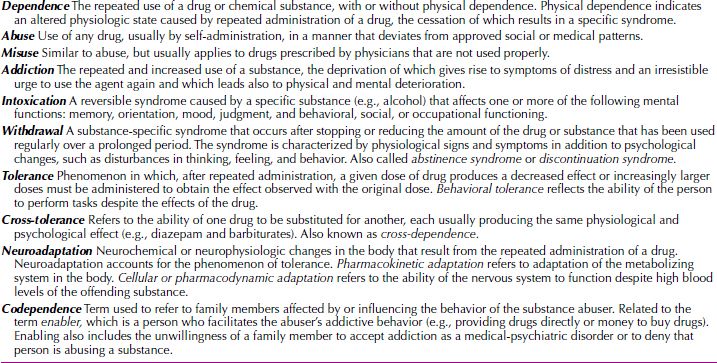

Table 20.1-1

Table 20.1-1

Terms Used in Substance-Related Disorders

EPIDEMIOLOGY

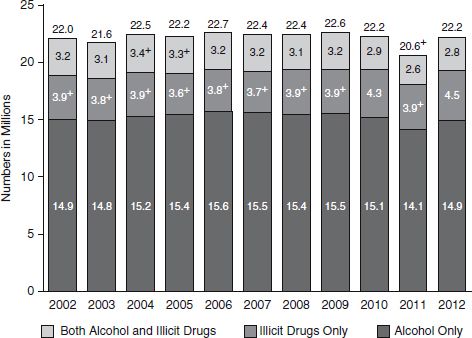

The National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) and other agencies, such as the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), conduct periodic surveys of the use of illicit drugs in the United States. As of 2012, it is estimated that more than 22 million persons older than the age of 12 years (about 10 percent of the total US population) were classified as having a substance-related disorder. Of this group, almost 15 million were dependent on, or abused, alcohol (Fig. 20.1-1).

FIGURE 20.1-1

Substance dependence or abuse in the past year among persons age 12 or over: 2002–2012. (From Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.)

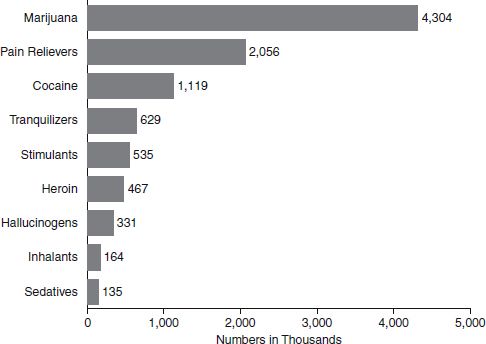

Figure 20.1-2 shows data from the surveys on the percentage of respondents who reported using various drugs. In 2012, 669,000 persons were dependent on, or abused, heroin; 1.7 percent (4.3 million) abused marijuana; 0.4 percent (1 million) abused cocaine; and 2 million were classified as dependent on, or abuse of, pain relievers.

FIGURE 20.1-2

Dependence on, or abuse of, specific illicit drugs within the past year among persons age 12 or older: 2010. (From Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.)

With regard to age at first use, those who started to use drugs at an earlier age (14 years or younger) were more likely to become addicted than those who started at a later age. This applied to all substances of abuse, but particularly to alcohol. Among adults aged 21 or older who first tried alcohol at age 14 or younger, 15 percent were classified as alcoholics compared with only 3 percent who first used alcohol at age 21 or older.

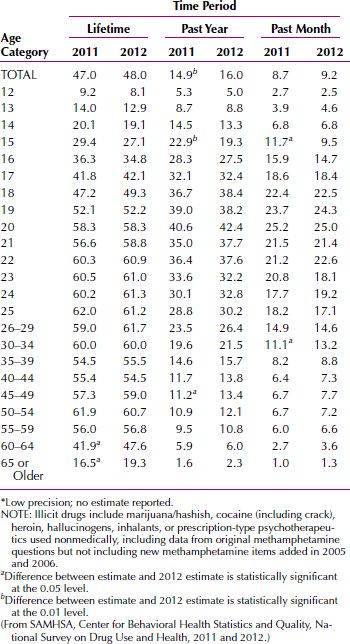

Rates of abuse also varied according to age (Table 20.1-2). In 2012, the rate for dependence or abuse is highest among adults age 18 to 25 (19 percent) compared to youths age 12 to 17 (6 percent) and adults age 26 or older (7 percent). After age 21, a general decline occurred with age. By age 65, only about 1 percent of persons have used an illicit substance within the past year, which lends credence to the clinical observation that addicts tend to “burn out” as they age.

Table 20.1-2

Table 20.1-2

Illicit Drug Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month, by Detailed Age Category: Percentages, 2011 and 2012

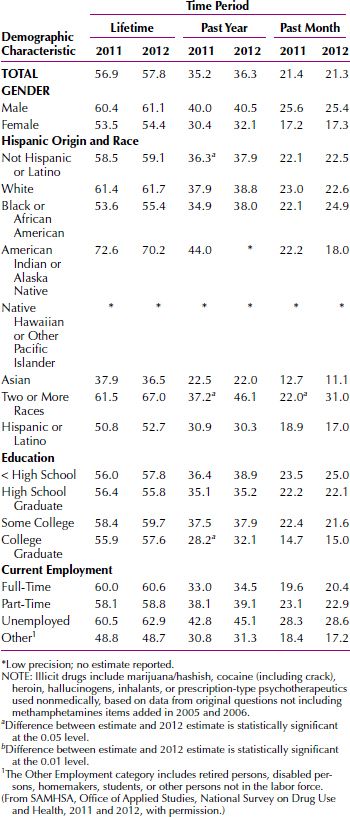

Table 20.1-3 summarizes data about the demographic characteristics of those who use illicit drugs. More men than women use drugs; the highest lifetime rate is among American Indian or Alaska Natives; whites are more affected than blacks or African Americans; those with some college education use more substances than those with less education; and the unemployed have higher rates that those with either part-time or full-time employment.

Table 20.1-3

Table 20.1-3

Illicit Drug Use in Lifetime, Past Year, and Past Month among Persons Aged 18 or Older, by Demographic Characteristics: Percentages, 2011 and 2012

Rates of substance dependence or abuse varied by region in the United States. In 2010, rates were slightly higher in the West (9 percent) and Midwest (9 percent) than in the Northeast (8 percent) and South (8 percent). Rates were similar in small metropolitan counties and large metropolitan counties (both at 9 percent) and were lowest in completely rural counties (7 percent). Rates are also higher among persons on parole or on supervised release from jail (34 percent vs. 9 percent). The number of persons driving while under the influence of drugs or alcohol is on a decline. The percentage driving under the influence of alcohol decreased from 14 percent in 2002 to 11 percent in 2010, and those driving under the influence of drugs decreased from 5 percent to 4 percent during the same period. A comprehensive survey of drug use and trends in the United States is available at www.samhsa.gov.

ETIOLOGY

The model of substance use disorders is the result of a process in which multiple interacting factors influence drug-using behavior and the loss of judgment with respect to decisions about using a given drug. Although the actions of a given drug are critical in the process, it is not assumed that all people who become dependent on the same drug experience its effects in the same way or are motivated by the same set of factors. Furthermore, it is postulated that different factors may be more or less important at different stages of the process. Thus, drug availability, social acceptability, and peer pressures may be the major determinants of initial experimentation with a drug, but other factors, such as personality and individual biology, probably are more important in how the effects of a given drug are perceived and the degree to which repeated drug use produces changes in the central nervous system (CNS). Still other factors, including the particular actions of the drug, may be primary determinants of whether drug use progresses to drug dependence, whereas still others may be important influences on the likelihood that drug use (1) leads to adverse effects or (2) to successful recovery from dependence.

It has been asserted that addiction is a “brain disease,” that the critical processes that transform voluntary drug-using behavior to compulsive drug use are changes in the structure and neurochemistry of the brain of the drug user. Sufficient evidence now indicates that such changes in relevant parts of the brain do occur. The perplexing and unanswered question is whether these changes are both necessary and sufficient to account for the drug-using behavior. Many argue that they are not, that the capacity of drug-dependent individuals to modify their drug-using behavior in response to positive reinforcers or aversive contingencies indicates that the nature of addiction is more complex and requires the interaction of multiple factors.

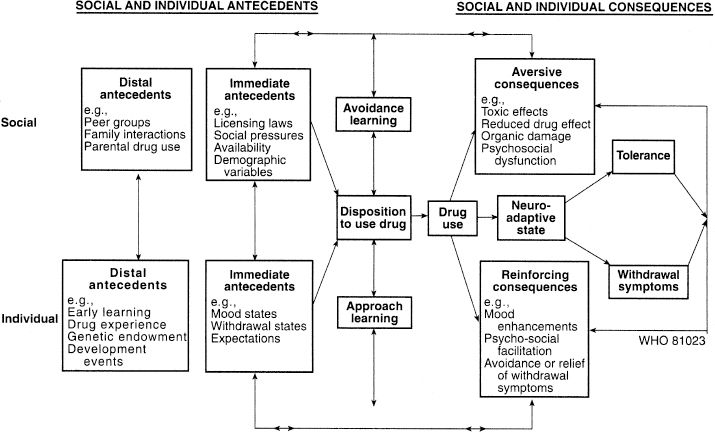

Figure 20.1-3 illustrates how various factors might interact in the development of drug dependence. The central element is the drug-using behavior itself. The decision to use a drug is influenced by immediate social and psychological situations as well as by the person’s more remote history. Use of the drug initiates a sequence of consequences that can be rewarding or aversive and which, through a process of learning, can result in a greater or lesser likelihood that the drug-using behavior will be repeated. For some drugs, use also initiates the biological processes associated with tolerance, physical dependence, and (not shown in the figure) sensitization. In turn, tolerance can reduce some of the adverse effects of the drug, permitting or requiring the use of larger doses, which then can accelerate or intensify the development of physical dependence. Above a certain threshold, the aversive qualities of a withdrawal syndrome provide a distinct recurrent motive for further drug use. Sensitization of motivational systems can increase the salience of drug-related stimuli.

FIGURE 20.1-3

World Health Organization schematic model of drug use and dependence. (From Edwards G, Arif A, Hodgson R. Nomenclature and classification of drug-and alcohol-related problems. A WHO memorandum. Bull WHO. 1981;59:225, with permission.)

Psychodynamic Factors

The range of psychodynamic theories about substance abuse reflects the various popular theories during the last 100 years. According to classic theories, substance abuse is a masturbatory equivalent (some heroin users describe the initial “rush” as similar to a prolonged sexual orgasm), a defense against anxious impulses, or a manifestation of oral regression (i.e., dependency). Recent psychodynamic formulations relate substance use as a reflection of disturbed ego functions (i.e., the inability to deal with reality). As a form of self-medication, alcohol may be used to control panic, opioids to diminish anger, and amphetamines to alleviate depression. Some addicts have great difficulty recognizing their inner emotional states, a condition called alexithymia (i.e., being unable to find words to describe their feelings).

Learning and Conditioning. Drug use, whether occasional or compulsive, can be viewed as behavior maintained by its consequences. Drugs can reinforce antecedent behaviors by terminating some noxious or aversive state such as pain, anxiety, or depression. In some social situations, the drug use, apart from its pharmacological effects, can be reinforcing if it results in special status or the approval of friends. Each use of the drug evokes rapid positive reinforcement, either as a result of the rush (the drug-induced euphoria), alleviation of disturbed affects, alleviation of withdrawal symptoms, or any combination of these effects. In addition, some drugs may sensitize neural systems to the reinforcing effects of the drug. Eventually, the paraphernalia (needles, bottles, cigarette packs) and behaviors associated with substance use can become secondary reinforcers, as well as cues signaling availability of the substance, and in their presence, craving or a desire to experience the effects increases.

Drug users respond to the drug-related stimuli with increased activity in limbic regions, including the amygdala and the anterior cingulate. Such drug-related activation of limbic areas has been demonstrated with a variety of drugs, including cocaine, opioids, and cigarettes (nicotine). Of interest, the same regions activated by cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine users are activated by sexual stimuli in both normal controls and cocaine users.

In addition to the operant reinforcement of drug-using and drug-seeking behaviors, other learning mechanisms probably play a role in dependence and relapse. Opioid and alcohol withdrawal phenomena can be conditioned (in the Pavlovian or classic sense) to environmental or interoceptive stimuli. For a long time after withdrawal (from opioids, nicotine, or alcohol), the addict exposed to environmental stimuli previously linked with substance use or withdrawal may experience conditioned withdrawal, conditioned craving, or both. The increased feelings of craving are not necessarily accompanied by symptoms of withdrawal. The most intense craving is elicited by conditions associated with the availability or use of the substance, such as watching someone else use heroin or light a cigarette or being offered some drug by a friend. Those learning and conditioning phenomena can be superimposed on any preexisting psychopathology, but preexisting difficulties are not required for the development of powerfully reinforced substance-seeking behavior.

Genetic Factors

Strong evidence from studies of twins, adoptees, and siblings brought up separately indicates that the cause of alcohol abuse has a genetic component. Many less conclusive data show that other types of substance abuse or substance dependence have a genetic pattern in their development. Researchers recently have used restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) in the study of substance abuse and substance dependence, and associations to genes that affect dopamine production have been postulated.

Neurochemical Factors

Receptors and Receptor Systems. With the exception of alcohol, researchers have identified particular neurotransmitters or neurotransmitter receptors involved with most substances of abuse. Some researchers base their studies on such hypotheses. The opioids, for example, act on opioid receptors. A person with too little endogenous opioid activity (e.g., low concentrations of endorphins) or with too much activity of an endogenous opioid antagonist may be at risk for developing opioid dependence. Even in a person with completely normal endogenous receptor function and neurotransmitter concentration, the long-term use of a particular substance of abuse may eventually modulate receptor systems in the brain so that the presence of the exogenous substance is needed to maintain homeostasis. Such a receptor-level process may be the mechanism for developing tolerance within the CNS. Demonstrating modulation of neurotransmitter release and neurotransmitter receptor function has proved difficult, however, and recent research focuses on the effects of substances on the second-messenger system and on gene regulation.

Pathways and Neurotransmitters

The major neurotransmitters possibly involved in developing substance abuse and substance dependence are the opioid, catecholamine (particularly dopamine), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) systems. The dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area are particularly important. These neurons project to the cortical and limbic regions, especially the nucleus accumbens. This pathway is probably involved in the sensation of reward and may be the major mediator of the effects of such substances as amphetamine and cocaine. The locus ceruleus, the largest group of adrenergic neurons, probably mediates the effects of the opiates and the opioids. These pathways have collectively been called the brain-reward circuitry.

COMORBIDITY

Comorbidity is the occurrence of two or more psychiatric disorders in a single patient at the same time. A high prevalence of additional psychiatric disorders is found among persons seeking treatment for alcohol, cocaine, or opioid dependence; some studies have shown that up to 50 percent of addicts have a comorbid psychiatric disorder. Although opioid, cocaine, and alcohol abusers with current psychiatric problems are more likely to seek treatment, those who do not seek treatment are not necessarily free of comorbid psychiatric problems; such persons may have social supports that enable them to deny the impact that drug use is having on their lives. Two large epidemiological studies have shown that even among representative samples of the population, those who meet the criteria for alcohol or drug abuse and dependence (excluding tobacco dependence) are also far more likely to meet the criteria for other psychiatric disorders also.

In various studies, a range of 35 to 60 percent of patients with substance abuse or substance dependence also meets the diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder. The range is even higher when investigators include persons who meet all the antisocial personality disorder diagnostic criteria, except the requirement that the symptoms started at an early age. That is, a high percentage of patients with substance abuse or substance dependence diagnoses have a pattern of antisocial behavior, whether it was present before the substance use started or developed during the course of the substance use. Patients with substance abuse or substance dependence diagnoses who have antisocial personality disorder are likely to use more illegal substances; to have more psychopathology; to be less satisfied with their lives; and to be more impulsive, isolated, and depressed than patients with antisocial personality disorders alone.

Depression and Suicide. Depressive symptoms are common among persons diagnosed with substance abuse or substance dependence. About one third to one half of all those with opioid abuse or opioid dependence and about 40 percent of those with alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence meet the criteria for major depressive disorder sometime during their lives. Substance use is also a major precipitating factor for suicide. Persons who abuse substances are about 20 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. About 15 percent of persons with alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence have been reported to commit suicide. This frequency of suicide is second only to the frequency in patients with major depressive disorder.

DIAGNOSTIC CLASSIFICATION

There are four major diagnostic categories in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5): (1) Substance Use Disorder; (2) Substance Intoxication; (3) Substance Withdrawal; and (4) Substance-Induced Mental Disorder.

Substance Use Disorder

Substance use disorder is the diagnostic term applied to the specific substance abused (e.g., alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder) that results from the prolonged use of the substance. The following points should be considered in making this diagnosis. These criteria apply to all substances of abuse.

A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by 2 (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

1. recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home (e.g., repeated absences or poor work performance related to substance use; substance-related absences, suspensions, or expulsions from school; neglect of children or household)

2. recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (e.g., driving an automobile or operating a machine when impaired by substance use)

3. continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance (e.g., arguments with spouse about consequences of intoxication, physical fights)

4. tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

a. a need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect

b. markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance

5. withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following:

a. the characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance

b. the same (or a closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms

6. the substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended

7. there is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use

8. a great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects

9. important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use

10. the substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance

11. craving or a strong desire or urge to use a specific substance.

Substance Intoxication

Substance intoxication is the diagnosis used to describe a syndrome (e.g., alcohol intoxication or simple drunkenness) characterized by specific signs and symptoms resulting from recent ingestion or exposure to the substance. A general description of substance intoxication includes the following points:

The development of a reversible substance-specific syndrome due to recent ingestion of (or exposure to) a substance. Note: Different substances may produce similar or identical syndromes.

The development of a reversible substance-specific syndrome due to recent ingestion of (or exposure to) a substance. Note: Different substances may produce similar or identical syndromes.

Clinically significant maladaptive behavioral or psychological changes that are due to the effect of the substance on the central nervous system (e.g., belligerence, mood lability, cognitive impairment, impaired judgment, impaired social or occupational functioning) and develop during or shortly after use of the substance.

Clinically significant maladaptive behavioral or psychological changes that are due to the effect of the substance on the central nervous system (e.g., belligerence, mood lability, cognitive impairment, impaired judgment, impaired social or occupational functioning) and develop during or shortly after use of the substance.

The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

Substance Withdrawal

Substance withdrawal is the diagnosis used to describe a substance specific syndrome that results from the abrupt cessation of heavy and prolonged use of a substance (e.g., opioid withdrawal). A general description of substance withdrawal requires the following criteria to be met:

The development of a substance-specific syndrome due to the cessation of (or reduction in) substance use that has been heavy and prolonged.

The development of a substance-specific syndrome due to the cessation of (or reduction in) substance use that has been heavy and prolonged.

The substance-specific syndrome causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

The substance-specific syndrome causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

In the discussion of each substance in the sections that follow, the generic tables listed above, derived from the DSM-5 can be applied. Thus, in place of the word substance, the clinician should indicate the specific substance or drug that is used or that caused intoxication or withdrawal.

TREATMENT AND REHABILITATION

Some persons who develop substance-related problems recover without formal treatment, especially as they age. For those patients with less severe disorders, such as nicotine addiction, relatively brief interventions are often as effective as more intensive treatments. Because these brief interventions do not change the environment, alter drug-induced brain changes, or provide new skills, a change in the patient’s motivation (cognitive change) probably has the best impact on the drug-using behavior. For those individuals who do not respond or whose dependence is more severe, a variety of interventions described below appear to be effective.

It is useful to distinguish among specific procedures or techniques (e.g., individual therapy, family therapy, group therapy, relapse prevention, and pharmacotherapy) and treatment programs. Most programs use a number of specific procedures and involve several professional disciplines as well as nonprofessionals who have special skills or personal experience with the substance problem being treated. The best treatment programs combine specific procedures and disciplines to meet the needs of the individual patient after a careful assessment.

No classification system is generally accepted for either the specific procedures used in treatment or programs using various combinations of procedures. This lack of standardized terminology for categorizing procedures and programs presents a problem, even when the field of interest is narrowed from substance problems in general to treatment for a single substance, such as alcohol, tobacco, or cocaine. Except in carefully monitored research projects, even the definitions of specific procedures (e.g., individual counseling, group therapy, and methadone maintenance) tend to be so imprecise that usually just what transactions are supposed to occur cannot be inferred. Nevertheless, for descriptive purposes, programs are often broadly grouped on the basis of one or more of their salient characteristics: whether the program is aimed at merely controlling acute withdrawal and consequences of recent drug use (detoxification) or is focused on longer-term behavioral change; whether the program makes extensive use of pharmacological interventions; and the degree to which the program is based on individual psychotherapy, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or other 12-step principles, or therapeutic community principles. For example, government agencies recently categorized publicly funded treatment programs for drug dependence as (1) methadone maintenance (mostly outpatient), (2) outpatient drug-free programs, (3) therapeutic communities, or (4) short-term inpatient programs.

Selecting a Treatment

Not all interventions are applicable to all types of substance use or dependence, and some of the more coercive interventions used for illicit drugs are not applicable to substances that are legally available, such as tobacco. Addictive behaviors do not change abruptly, but through a series of stages. Five stages in this gradual process have been proposed: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. For some types of addictions the therapeutic alliance is enhanced when the treatment approach is tailored to the patient’s stage of readiness to change. Interventions for some drug use disorders may have a specific pharmacological agent as an important component; for example, disulfiram, naltrexone (ReVia), or acamprosate for alcoholism; methadone (Dolophine), levomethadyl acetate (ORLAAM), or buprenorphine (Buprenex) for heroin addiction; and nicotine delivery devices or bupropion (Zyban) for tobacco dependence. Not all interventions are likely to be useful to health care professionals. For example, many youthful offenders with histories of drug use or dependence are now remanded to special facilities (boot camps); other programs for offenders (and sometimes for employees) rely almost exclusively on the deterrent effect of frequent urine testing; and a third group are built around religious conversion or rededication in a specific religious sect or denomination. In contrast to the numerous studies suggesting some value for brief interventions for smoking and for problem drinking, few controlled studies are conducted of brief interventions for those seeking treatment for dependence on illicit drugs.

In general, brief interventions (e.g., a few weeks of detoxification, whether in or out of a hospital) used for persons who are severely dependent on illicit opioids have limited effect on outcome measured a few months later. Substantial reductions in illicit drug use, antisocial behaviors, and psychiatric distress among patients dependent on cocaine or heroin are much more likely following treatment lasting at least 3 months. Such a time-in-treatment effect is seen across very different modalities, from residential therapeutic communities to ambulatory methadone maintenance programs. Although some patients appear to benefit from a few days or weeks of treatment, a substantial percentage of users of illicit drugs drop out (or are dropped) from treatment before they have achieved significant benefits.

Some of the variance in treatment outcomes can be attributed to differences in the characteristics of patients entering treatment and by events and conditions following treatment. Programs based on similar philosophical principles and using what seem to be similar therapeutic procedures vary greatly in effectiveness, however. Some of the differences among programs that seem to be similar reflect the range and intensity of services offered. Programs with professionally trained staffs that provide more comprehensive services to patients with more severe psychiatric difficulties are more likely able to retain those patients in treatment and help them make positive changes. Differences in the skills of individual counselors and professionals can strongly affect outcomes.

Such generalizations concerning programs serving illicit drug users may not hold for programs dealing with those seeking treatment for alcohol, tobacco, or even cannabis problems uncomplicated by heavy use of illicit drugs. In such cases, relatively brief periods of individual or group counseling can produce long-lasting reductions in drug use. The outcomes usually considered in programs dealing with illicit drugs have typically included measures of social functioning, employment, and criminal activity, as well as decreased drug-using behavior.

Treatment of Comorbidity

Treatment of the severely mentally ill (primarily those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders) who are also drug dependent continues to pose problems for clinicians. Although some special facilities have been developed that use both antipsychotic drugs and therapeutic community principles, for the most part, specialized addiction agencies have difficulty treating these patients. Generally, integrated treatment in which the same staff can treat both the psychiatric disorder and the addiction is more effective than either parallel treatment (a mental health and a specialty addiction program providing care concurrently) or sequential treatment (treating either the addiction or the psychiatric disorder first and then dealing with the comorbid condition).

Services and Outcome

The extension of managed care into the public sector has produced a major reduction in the use of hospital-based detoxification and virtual disappearance of residential rehabilitation programs for alcoholics. Managed-care organizations, however, tend to assume that the relatively brief courses of outpatient counseling that are effective with private-sector alcoholic patients are also effective with patients who are dependent on illicit drugs and who have minimal social supports. For the present, the trend is to provide the care that costs the least over the short term and to ignore studies showing that more services can produce better long-term outcomes.

Treatment is often a worthwhile social expenditure. For example, treatment of antisocial illicit drug users in outpatient settings can decrease antisocial behavior and reduce rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seroconversion that more than offset the treatment cost. Treatment in a prison setting can decrease post-release costs associated with drug use and rearrests. Despite such evidence, problems exist in maintaining public support for treatment of substance dependence in both the public and private sectors. This lack of support suggests that these problems continue to be viewed, at least in part, as moral failings rather than as medical disorders.

REFERENCES

Bonder BR. Substance-related disorders. In: Bonder BR. Psychopathology and Function. 4thed. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK Inc.; 2010:103.

Clark R, Samnaliev M, McGovern MP. Impact of substance disorders on medical expenditures for Medicaid beneficiaries with behavioral health disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:35.

Ersche KD, Jones PS, Williams GB, Turton AJ, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET: Abnormal brain structure implicated in stimulant drug addiction. Science. 2012; 335:601.

Fazel S, Långström N, Hjern A, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2016.

Frances RJ, Miller SI, Mack AH, eds. Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders. 3rd ed. New York: The Guildford Press; 2011.

Harper AD. Substance-related disorders. In: Thornhill J. 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:109.

Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M: DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:834.

Hoblyn JC, Balt SL, Woodard SA, Brooks JO. Substance use disorders as risk factors for psychiatric hospitalization in bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009; 60:55.

Karoly HC, Harlaar N, Hutchison KE. Substance use disorders: A theory-driven approach to the integration of genetics and neuroimaging. Annals N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1282:71.

Krenek M, Maisto SA. Life events and treatment outcomes among individuals with substance use disorders: A narrative review. Clin Psych Rev. 2013;33:470.

Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Fletcher L. Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:43.

Mojtabai R, Chen LY, Kaufmann CN, Crum RM. Comparing barriers to mental health treatment and substance use disorder treatment among individuals with comorbid major depression and substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(2):268–273.

Strain EC, Anthony JC. Substance-related disorders: Introduction and overview. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:1237.

Unger JB. The most critical unresolved issues associated with race, ethnicity, culture, and substance use. Subst Use Misuse, 2012;47:390.

20.2 Alcohol-Related Disorders

20.2 Alcohol-Related Disorders

Alcoholism is among the most common psychiatric disorders observed in the Western world. Alcohol-related problems in the United States contribute to 2 million injuries each year, including 22,000 deaths. Recent years have witnessed a blossoming of clinically relevant research regarding alcohol abuse and dependence, including information on specific genetic influences, the clinical course of these conditions, and the development of new and helpful treatments.

Alcohol is a potent drug that causes both acute and chronic changes in almost all neurochemical systems. Thus alcohol abuse can produce serious temporary psychological symptoms including depression, anxiety, and psychoses. Long-term, escalating levels of alcohol consumption can produce tolerance as well as such intense adaptation of the body that cessation of use can precipitate a withdrawal syndrome usually marked by insomnia, evidence of hyperactivity of the autonomic nervous system, and feelings of anxiety. Therefore, in an adequate evaluation of life problems and psychiatric symptoms in a patient, the clinician must consider the possibility that the clinical situation reflects the effects of alcohol.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Psychiatrists need to be concerned about alcoholism because this condition is common; intoxication and withdrawal mimic many major psychiatric disorders, and the usual person with alcoholism does not fit the stereotype (i.e., so called “nasty knock-down drinkers”).

Prevalence of Drinking

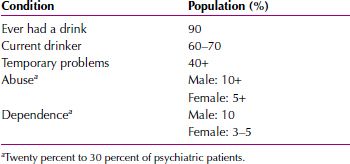

At some time during life, 90 percent of the population in the United States drinks, with most people beginning their alcohol intake in the early to middle teens (Table 20.2-1). By the end of high school, 80 percent of students have consumed alcohol, and more than 60 percent have been intoxicated. At any time, two of three men are drinkers, with a ratio of persisting alcohol intake of approximately 1.3 men to 1.0 women, and the highest prevalence of drinking from the middle or late teens to the mid-20s.

Table 20.2-1

Table 20.2-1

Alcohol Epidemiology

Men and women with higher education and income are most likely to imbibe, and, among religious denominations, Jews have the highest proportion who consume alcohol but among the lowest rates of alcohol dependence. Other ethnicities, such as the Irish, have higher rates of severe alcohol problems, but they also have significantly higher rates of abstentions. Some estimates show that more than 60 percent of men and women in some Native American and Inuit tribes have been alcohol dependent at some time. In the United States, the average adult consumes 2.2 gallons of absolute alcohol a year, a decrease from 2.7 gallons per capita in 1981.

Drinking alcohol-containing beverages is generally considered an acceptable habit in the United States. About 90 percent of all US residents have had an alcohol-containing drink at least once in their lives, and about 51 percent of all US adults are current users of alcohol. After heart disease and cancer, alcohol-related disorders constitute the third largest health problem in the United States today. Beer accounts for about one half of all alcohol consumption, liquor for about one third, and wine for about one sixth. About 30 to 45 percent of all adults in the United States have had at least one transient episode of an alcohol-related problem, usually an alcohol-induced amnestic episode (e.g., a blackout), driving a motor vehicle while intoxicated, or missing school or work because of excessive drinking. About 10 percent of women and 20 percent of men have met the diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse during their lifetimes, and 3 to 5 percent of women and 10 percent of men have met the diagnostic criteria for the more serious diagnosis of alcohol dependence during their lifetimes. About 200,000 deaths each year are directly related to alcohol abuse. The common causes of death among persons with the alcohol-related disorders are suicide, cancer, heart disease, and hepatic disease. Although persons involved in automotive fatalities do not always meet the diagnostic criteria for an alcohol-related disorder, drunk drivers are involved in about 50 percent of all automotive fatalities, and this percentage increases to about 75 percent when only accidents occurring in the late evening are considered. Alcohol use and alcohol-related disorders are associated with about 50 percent of all homicides and 25 percent of all suicides. Alcohol abuse reduces life expectancy by about 10 years, and alcohol leads all other substances in substance-related deaths. Table 20.2-2 lists other epidemiological data about alcohol use.

Table 20.2-2

Table 20.2-2

Epidemiological Data for Alcohol-Related Disorders

COMORBIDITY

The psychiatric diagnoses most commonly associated with the alcohol-related disorders are other substance-related disorders, antisocial personality disorder, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Although the data are somewhat controversial, most suggest that persons with alcohol-related disorders have a markedly higher suicide rate than the general population.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

A relation between antisocial personality disorder and alcohol-related disorders has frequently been reported. Some studies suggest that antisocial personality disorder is particularly common in men with an alcohol-related disorder and can precede the development of the alcohol-related disorder. Other studies, however, suggest that antisocial personality disorder and alcohol-related disorders are completely distinct entities that are not causally related.

Mood Disorders

About 30 to 40 percent of persons with an alcohol-related disorder meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder sometime during their lifetimes. Depression is more common in women than in men with these disorders. Several studies reported that depression is likely to occur in patients with alcohol-related disorders who have a high daily consumption of alcohol and a family history of alcohol abuse. Persons with alcohol-related disorders and major depressive disorder are at great risk for attempting suicide and are likely to have other substance-related disorder diagnoses. Some clinicians recommend antidepressant drug therapy for depressive symptoms that remain after 2 to 3 weeks of sobriety. Patients with bipolar I disorder are thought to be at risk for developing an alcohol-related disorder; they may use alcohol to self-medicate their manic episodes. Some studies have shown that persons with both alcohol-related disorder and depressive disorder diagnoses have concentrations of dopamine metabolites (homovanillic acid) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Anxiety Disorders

Many persons use alcohol for its efficacy in alleviating anxiety. Although the comorbidity between alcohol-related disorders and mood disorders is fairly widely recognized, it is less well known that perhaps 25 to 50 percent of all persons with alcohol-related disorders also meet the diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder. Phobias and panic disorder are particularly frequent comorbid diagnoses in these patients. Some data indicate that alcohol may be used in an attempt to self-medicate symptoms of agoraphobia or social phobia, but an alcohol-related disorder is likely to precede the development of panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder.

Suicide

Most estimates of the prevalence of suicide among persons with alcohol-related disorders range from 10 to 15 percent, although alcohol use itself may be involved in a much higher percentage of suicides. Some investigators have questioned whether the suicide rate among persons with alcohol-related disorders is as high as the numbers suggest. Factors that have been associated with suicide among persons with alcohol-related disorders include the presence of a major depressive episode, weak psychosocial support systems, a serious coexisting medical condition, unemployment, and living alone.

ETIOLOGY

Many factors affect the decision to drink, the development of temporary alcohol-related difficulties in the teenage years and the 20s, and the development of alcohol dependence. The initiation of alcohol intake probably depends largely on social, religious, and psychological factors, although genetic characteristics might also contribute. The factors that influence the decision to drink or those that contribute to temporary problems might differ, however, from those that add to the risk for the severe, recurring problems of alcohol dependence.

A similar interplay between genetic and environmental influences contributes to many medical and psychiatric conditions, and, thus, a review of these factors in alcoholism offers information about complex genetic disorders overall. Dominant or recessive genes, although important, explain only relatively rare conditions. Most disorders have some level of genetic predisposition that usually relates to a series of different genetically influenced characteristics, each of which increases or decreases the risk for the disorder.

It is likely that a series of genetic influences combine to explain approximately 60 percent of the proportion of risk for alcoholism, with environment responsible for the remaining proportion of the variance. The divisions offered in this section, therefore, are more heuristic than real, because it is the combination of a series of psychological, sociocultural, biological, and other factors that are responsible for the development of severe, repetitive alcohol-related life problems.

Psychological Theories

A variety of theories relate to the use of alcohol to reduce tension, increase feelings of power, and decrease the effects of psychological pain. Perhaps the greatest interest has been paid to the observation that people with alcohol-related problems often report that alcohol decreases their feelings of nervousness and helps them cope with the day-to-day stresses of life. The psychological theories are built, in part, on the observation among nonalcoholic people that the intake of low doses of alcohol in a tense social setting or after a difficult day can be associated with an enhanced feeling of well-being and an improved ease of interactions. In high doses, especially at falling blood alcohol levels, however, most measures of muscle tension and psychological feelings of nervousness and tension are increased. Thus, tension-reducing effects of this drug might have an impact most on light to moderate drinkers or add to the relief of withdrawal symptoms, but play a minor role in causing alcoholism. The theories that focus on alcohol’s potential to enhance feelings of being powerful and sexually attractive and to decrease the effects of psychological pain are difficult to evaluate definitively.

Psychodynamic Theories

Perhaps related to the disinhibiting or anxiety-lowering effects of lower doses of alcohol is the hypothesis that some people may use this drug to help them deal with self-punitive harsh superegos and to decrease unconscious stress levels. In addition, classic psychoanalytical theory hypothesizes that at least some alcoholic people may have become fixated at the oral stage of development and use alcohol to relieve their frustrations by taking the substance by mouth. Hypotheses regarding arrested phases of psychosexual development, although heuristically useful, have had little effect on the usual treatment approaches and are not the focus of extensive ongoing research. Similarly, most studies have not been able to document an “addictive personality” present in most alcoholics and associated with a propensity to lack control of intake of a wide range of substances and foods. Although pathological scores on personality tests are often seen during intoxication, withdrawal, and early recovery, many of these characteristics are not found to predate alcoholism, and most disappear with abstinence. Similarly, prospective studies of children of alcoholics who themselves have no co-occurring disorders usually document high risks mostly for alcoholism. As is described later in this text, one partial exception occurs with the extreme levels of impulsivity seen in the 15 to 20 percent of alcoholic men with antisocial personality disorder, because they have high risks for criminality, violence, and multiple substance dependencies.

Behavioral Theories

Expectations about the rewarding effects of drinking, cognitive attitudes toward responsibility for one’s behavior, and subsequent reinforcement after alcohol intake all contribute to the decision to drink again after the first experience with alcohol and to continue to imbibe despite problems. These issues are important in efforts to modify drinking behaviors in the general population, and they contribute to some important aspects of alcoholic rehabilitation.

Sociocultural Theories

Sociocultural theories are often based on extrapolations from social groups that have high and low rates of alcoholism. Theorists hypothesize that ethnic groups, such as Jews, who introduce children to modest levels of drinking in a family atmosphere and eschew drunkenness have low rates of alcoholism. Some other groups, such as Irish men or some American Indian tribes with high rates of abstention but a tradition of drinking to the point of drunkenness among drinkers, are believed to have high rates of alcoholism. These theories, however, often depend on stereotypes that tend to be erroneous, and prominent exceptions to these rules exist. For example, some theories based on observations of the Irish and the French have incorrectly predicted high rates of alcoholism among the Italians.

Yet, environmental events, presumably including cultural factors, account for as much as 40 percent of the alcoholism risk. Thus, although these are difficult to study, it is likely that cultural attitudes toward drinking, drunkenness, and personal responsibility for consequences are important contributors to the rates of alcohol-related problems in a society. In the final analysis, social and psychological theories are probably highly relevant, because they outline factors that contribute to the onset of drinking, the development of temporary alcohol-related life difficulties, and even alcoholism. The problem is how to gather relatively definitive data to support or refute the theories.

Childhood History

Researchers have identified several factors in the childhood histories of persons with later alcohol-related disorders and in children at high risk for having an alcohol-related disorder because one or both of their parents are affected. In experimental studies, children at high risk for alcohol-related disorders have been found to possess, on average, a range of deficits on neurocognitive testing, low amplitude of the P300 wave on evoked potential testing, and a variety of abnormalities on electroencephalography (EEG) recordings. Studies of high-risk offspring in their 20s have also shown a generally blunted effect of alcohol compared with that seen in persons whose parents have not been diagnosed with alcohol-related disorder. These findings suggest that a heritable biological brain function may predispose a person to an alcohol-related disorder. A childhood history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, or both, increases a child’s risk for an alcohol-related disorder as an adult. Personality disorders, especially antisocial personality disorder, as noted earlier, also predispose a person to an alcohol-related disorder.

Genetic Theories

Importance of Genetic Influences. Four lines of evidence support the conclusion that alcoholism is genetically influenced. First, a threefold to fourfold increased risk for severe alcohol problems is seen in close relatives of alcoholic people. The rate of alcohol problems increases with the number of alcoholic relatives, the severity of their illness, and the closeness of their genetic relationship to the person under study. The family investigations do little to separate the importance of genetics and environment, and the second approach, twin studies, takes the data a step further. The rate of similarity, or concordance, for severe alcohol-related problems is significantly higher in identical twins of alcoholic individuals than in fraternal twins in most investigations, which estimate that genes explain 60 percent of the variance, with the remainder relating to nonshared, probably adult environmental influences. Third, the adoption-type studies have all revealed a significantly enhanced risk for alcoholism in the offspring of alcoholic parents, even when the children had been separated from their biological parents close to birth and raised without any knowledge of the problems within the biological family. The risk for severe alcohol-related difficulties is not further enhanced by being raised by an alcoholic adoptive family. Finally, studies in animals support the importance of a variety of yet-to-be-identified genes in the free-choice use of alcohol, subsequent levels of intoxication, and some consequences.

EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL

The term alcohol refers to a large group of organic molecules that have a hydroxyl group (-OH) attached to a saturated carbon atom. Ethyl alcohol, also called ethanol, is the common form of alcohol; sometimes referred to as beverage alcohol, ethyl alcohol is used for drinking. The chemical formula for ethanol is CH3-CH2-OH.

The characteristic tastes and flavors of alcohol-containing beverages result from their methods of production, which produce various congeners in the final product, including methanol, butanol, aldehydes, phenols, tannins, and trace amounts of various metals. Although the congeners may confer some differential psychoactive effects on the various alcohol-containing beverages, these differences are minimal compared with the effects of ethanol itself. A single drink is usually considered to contain about 12 g of ethanol, which is the content of 12 ounces of beer (7.2 proof, 3.6 percent ethanol in the United States), one 4-ounce glass of nonfortified wine, or 1 to 1.5 ounces of an 80-proof (40 percent ethanol) liquor (e.g., whiskey or gin). In calculating patients’ alcohol intake, however, clinicians should be aware that beers vary in their alcohol content, that beers are available in small and large cans and mugs, that glasses of wine range from 2 to 6 ounces, and that mixed drinks at some bars and in most homes contain 2 to 3 ounces of liquor. Nonetheless, using the moderate sizes of drinks, clinicians can estimate that a single drink increases the blood alcohol level of a 150-pound man by 15 to 20 mg/dL, which is about the concentration of alcohol that an average person can metabolize in 1 hour.

The possible beneficial effects of alcohol have been publicized, especially by the makers and the distributors of alcohol. Most attention has been focused on some epidemiological data that suggest that one or two glasses of red wine each day lower the incidence of cardiovascular disease; these findings, however, are highly controversial.

Absorption

About 10 percent of consumed alcohol is absorbed from the stomach, and the remainder from the small intestine. Peak blood concentration of alcohol is reached in 30 to 90 minutes and usually in 45 to 60 minutes, depending on whether the alcohol was ingested on an empty stomach (which enhances absorption) or with food (which delays absorption). The time to peak blood concentration also depends on the time during which the alcohol was consumed; rapid drinking reduces the time to peak concentration, slower drinking increases it. Absorption is most rapid with beverages containing 15 to 30 percent alcohol (30 to 60 proof). There is some dispute about whether carbonation (e.g., in champagne and in drinks mixed with seltzer) enhances the absorption of alcohol.

The body has protective devices against inundation by alcohol. For example, if the concentration of alcohol in the stomach becomes too high, mucus is secreted and the pyloric valve closes. These actions slow the absorption and keep the alcohol from passing into the small intestine, where there are no significant restraints on absorption. Thus, a large amount of alcohol can remain unabsorbed in the stomach for hours. Furthermore, pylorospasm often results in nausea and vomiting.

Once alcohol is absorbed into the bloodstream, it is distributed to all body tissues. Because alcohol is uniformly dissolved in the body’s water, tissues containing a high proportion of water receive a high concentration of alcohol. The intoxicating effects are greater when the blood alcohol concentration is rising than when it is falling (the Mellanby effects). For this reason, the rate of absorption bears directly on the intoxication response.

Metabolism

About 90 percent of absorbed alcohol is metabolized through oxidation in the liver; the remaining 10 percent is excreted unchanged by the kidneys and lungs. The rate of oxidation by the liver is constant and independent of the body’s energy requirements. The body can metabolize about 15 mg/dL per hour, with a range of 10 to 34 mg/dL per hour. That is, the average person oxidizes three fourths of an ounce of 40 percent (80 proof) alcohol in an hour. In persons with a history of excessive alcohol consumption, upregulation of the necessary enzymes results in rapid alcohol metabolism.

Alcohol is metabolized by two enzymes: alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase. ADH catalyzes the conversion of alcohol into acetaldehyde, which is a toxic compound; aldehyde dehydrogenase catalyzes the conversion of acetaldehyde into acetic acid. Aldehyde dehydrogenase is inhibited by disulfiram (Antabuse), often used in the treatment of alcohol-related disorders. Some studies have shown that women have a lower ADH blood content than men; this fact may account for woman’s tendency to become more intoxicated than men after drinking the same amount of alcohol. The decreased function of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in some Asian persons can also lead to easy intoxication and toxic symptoms.

Effects on the Brain

Biochemistry. In contrast to most other substances of abuse with identified receptor targets—such as the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor of phencyclidine (PCP)—no single molecular target has been identified as the mediator for the effects of alcohol. The longstanding theory about the biochemical effects of alcohol concerns its effects on the membranes of neurons. Data support the hypothesis that alcohol produces its effects by intercalating itself into membranes and, thus, increasing fluidity of the membranes with short-term use. With long-term use, however, the theory hypothesizes that the membranes become rigid or stiff. The fluidity of the membranes is critical to normal functioning of receptors, ion channels, and other membrane-bound functional proteins. In recent studies, researchers have attempted to identify specific molecular targets for the effects of alcohol. Most attention has been focused on the effects of alcohol at ion channels. Specifically, studies have found that alcohol ion channel activities associated with the nicotinic acetylcholine, serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3), and GABA type A (GABAA) receptors are enhanced by alcohol, whereas ion channel activities associated with glutamate receptors and voltage-gated calcium channels are inhibited.

Behavioral Effects. As the net result of the molecular activities, alcohol functions as a depressant much like the barbiturates and the benzodiazepines, with which alcohol has some cross-tolerance and cross-dependence. At a level of 0.05 percent alcohol in the blood, thought, judgment, and restraint are loosened and sometimes disrupted. At a concentration of 0.1 percent, voluntary motor actions usually become perceptibly clumsy. In most states, legal intoxication ranges from 0.1 to 0.15 percent blood alcohol level. At 0.2 percent, the function of the entire motor area of the brain is measurably depressed, and the parts of the brain that control emotional behavior are also affected. At 0.3 percent, a person is commonly confused or may become stuporous; at 0.4 to 0.5 percent, the person falls into a coma. At higher levels, the primitive centers of the brain that control breathing and heart rate are affected, and death ensues secondary to direct respiratory depression or the aspiration of vomitus. Persons with long-term histories of alcohol abuse, however, can tolerate much higher concentrations of alcohol than can alcohol-naïve persons; their alcohol tolerance may cause them to falsely appear less intoxicated than they really are.

Sleep Effects. Although alcohol consumed in the evening usually increases the ease of falling asleep (decreased sleep latency), alcohol also has adverse effects on sleep architecture. Specifically, alcohol use is associated with a decrease in rapid eye movement sleep (REM or dream sleep) and deep sleep (stage 4) and more sleep fragmentation, with more and longer episodes of awakening. Therefore, the idea that drinking alcohol helps persons fall asleep is a myth.

Other Physiological Effects

Liver. The major adverse effects of alcohol use are related to liver damage. Alcohol use, even as short as week-long episodes of increased drinking, can result in an accumulation of fats and proteins, which produce the appearance of a fatty liver, sometimes found on physical examination as an enlarged liver. The association between fatty infiltration of the liver and serious liver damage remains unclear. Alcohol use, however, is associated with the development of alcoholic hepatitis and hepatic cirrhosis.

Gastrointestinal System. Long-term heavy drinking is associated with developing esophagitis, gastritis, achlorhydria, and gastric ulcers. The development of esophageal varices can accompany particularly heavy alcohol abuse; the rupture of the varices is a medical emergency often resulting in death by exsanguination. Disorders of the small intestine occasionally occur, and pancreatitis, pancreatic insufficiency, and pancreatic cancer are also associated with heavy alcohol use. Heavy alcohol intake can interfere with the normal processes of food digestion and absorption; as a result, consumed food is inadequately digested. Alcohol abuse also appears to inhibit the intestine’s capacity to absorb various nutrients, such as vitamins and amino acids. This effect, coupled with the often poor dietary habits of those with alcohol-related disorders, can cause serious vitamin deficiencies, particularly of the B vitamins.

Other Bodily Systems. Significant intake of alcohol has been associated with increased blood pressure, dysregulation of lipoprotein and triglyceride metabolism, and increased risk for myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular disease. Alcohol has been shown to affect the hearts of nonalcoholic persons who do not usually drink, increasing the resting cardiac output, the heart rate, and the myocardial oxygen consumption. Evidence indicates that alcohol intake can adversely affect the hematopoietic system and can increase the incidence of cancer, particularly head, neck, esophageal, stomach, hepatic, colonic, and lung cancer. Acute intoxication may also be associated with hypoglycemia, which, when unrecognized, may be responsible for some of the sudden deaths of persons who are intoxicated. Muscle weakness is another side effect of alcoholism. Recent evidence shows that alcohol intake raises the blood concentration of estradiol in women. The increase in estradiol correlates with the blood alcohol level.

Laboratory Tests. The adverse effects of alcohol appear in common laboratory tests, which can be useful diagnostic aids in identifying persons with alcohol-related disorders. The γ-glutamyl transpeptidase levels are high in about 80 percent of those with alcohol-related disorders, and the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is high in about 60 percent, more so in women than in men. Other laboratory test values that may be high in association with alcohol abuse are those of uric acid, triglycerides, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

Drug Interactions

The interaction between alcohol and other substances can be dangerous, even fatal. Certain substances, such as alcohol and phenobarbital (Luminal), are metabolized by the liver, and their prolonged use can lead to acceleration of their metabolism. When persons with alcohol-related disorders are sober, this accelerated metabolism makes them unusually tolerant to many drugs such as sedatives and hypnotics; when they are intoxicated, however, these drugs compete with the alcohol for the same detoxification mechanisms, and potentially toxic concentrations of all involved substances can accumulate in the blood.

The effects of alcohol and other central nervous system (CNS) depressants are usually synergistic. Sedatives, hypnotics, and drugs that relieve pain, motion sickness, head colds, and allergy symptoms must be used with caution by persons with alcohol-related disorders. Narcotics depress the sensory areas of the cerebral cortex and can produce pain relief, sedation, apathy, drowsiness, and sleep; high doses can result in respiratory failure and death. Increasing the dosages of sedative-hypnotic drugs, such as chloral hydrate (Noctec) and benzodiazepines, especially when they are combined with alcohol, produces a range of effects from sedation to motor and intellectual impairment to stupor, coma, and death. Because sedatives and other psychotropic drugs can potentiate the effects of alcohol, patients should be instructed about the dangers of combining CNS depressants and alcohol, particularly when they are driving or operating machinery.

DISORDERS

Alcohol Use Disorder

Diagnosis and Clinical Features. In the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), all substance use disorders use the same general criteria for dependence and abuse (see Section 20.1). A need for daily use of large amounts of alcohol for adequate functioning, a regular pattern of heavy drinking limited to weekends, and long periods of sobriety interspersed with binges of heavy alcohol intake lasting for weeks or months strongly suggest alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse. The drinking patterns are often associated with certain behaviors: the inability to cut down or stop drinking; repeated efforts to control or reduce excessive drinking by “going on the wagon” (periods of temporary abstinence) or by restricting drinking to certain times of the day; binges (remaining intoxicated throughout the day for at least 2 days); occasional consumption of a fifth of spirits (or its equivalent in wine or beer); amnestic periods for events occurring while intoxicated (blackouts); the continuation of drinking despite a serious physical disorder that the person knows is exacerbated by alcohol use; and drinking nonbeverage alcohol, such as fuel and commercial products containing alcohol. In addition, persons with alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse show impaired social or occupational functioning because of alcohol use (e.g., violence while intoxicated, absence from work, job loss), legal difficulties (e.g., arrest for intoxicated behavior and traffic accidents while intoxicated), and arguments or difficulties with family members or friends about excessive alcohol consumption.

Mark, a 45-year-old divorced man, was examined in a hospital emergency room because he had been confused and unable to care for himself of the preceding 3 days. His brother, who brought him to the hospital, reported that the patient has consumed large quantities of beer and wine daily for more than 5 years. His home and job lives were reasonably stable until his divorce 5 years prior. The brother indicated that Mark’s drinking pattern since the divorce has been approximately 5 beers and a fourth of wine a day. Mark often experienced blackouts from drinking and missed days of work frequently. As a result, Mark has lost several jobs in the past 5 years. Although he usually provides for himself marginally with small jobs, 3 days earlier he ran out of money and alcohol and resorted to panhandling on the streets for cash to buy food. Mark had been poorly nourished, having one meal per day at best and was evidently relying on beer as his prime source of nourishment.

On examination, Mark alternates between apprehension and chatty, superficial warmth. He is pretty keyed up and talks constantly in a rambling and unfocused manner. His recognition of the physician varies; at times he recognizes him and other times he becomes confused and believes the doctor to be his other brother who lives in another state. On two occasions he referred to the physician by said brother’s name and asked when he arrived in town, evidently having lost track of the interview up to that point. He has a gross hand tremor at rest and is disoriented to time. He believes he’s in a parking lot rather than a hospital. Efforts at memory and calculation testing fail because Mark’s attention shifts so rapidly.

Subtypes of Alcohol Dependence. Various researchers have attempted to divide alcohol dependence into subtypes based primarily on phenomenological characteristics. One recent classification notes that type A alcohol dependence is characterized by late onset, few childhood risk factors, relatively mild dependence, few alcohol-related problems, and little psychopathology. Type B alcohol dependence is characterized by many childhood risk factors, severe dependence, an early onset of alcohol-related problems, much psychopathology, a strong family history of alcohol abuse, frequent polysubstance abuse, a long history of alcohol treatment, and a lot of severe life stresses. Some researchers have found that type A persons who are alcohol dependent may respond to interactional psychotherapies, whereas type B persons who are alcohol dependent may respond to training in coping skills.

Other subtyping schemes of alcohol dependence have received fairly wide recognition in the literature. One group of investigators proposed three subtypes: earlystage problem drinkers, who do not yet have complete alcohol dependence syndromes; affiliative drinkers, who tend to drink daily in moderate amounts in social settings; and schizoid-isolated drinkers, who have severe dependence and tend to drink in binges and often alone.

Another investigator described gamma alcohol dependence, which is thought to be common in the United States and represents the alcohol dependence seen in those who are active in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). This variant concerns control problems in which persons are unable to stop drinking once they start. When drinking is terminated as a result of ill health or lack of money, these persons can abstain for varying periods. In delta alcohol dependence, perhaps more common in Europe than in the United States, persons who are alcohol dependent must drink a certain amount each day but are unaware of a lack of control. The alcohol use disorder may not be discovered until a person who must stop drinking for some reason exhibits withdrawal symptoms.

Another researcher has suggested a type I, male-limited variety of alcohol dependence, characterized by late onset, more evidence of psychological than of physical dependence, and the presence of guilt feelings. Type II, male-limited alcohol dependence is characterized by onset at an early age, spontaneous seeking of alcohol for consumption, and a socially disruptive set of behaviors when intoxicated.

Four subtypes of alcoholism were postulated by still another investigator. The first is antisocial alcoholism, typically with a predominance in men, a poor prognosis, early onset of alcohol-related problems, and a close association with antisocial personality disorder. The second is developmentally cumulative alcoholism, with a primary tendency for alcohol abuse that is exacerbated with time as cultural expectations foster increased opportunities to drink. The third is negative-affect alcoholism, which is more common in women than in men; according to this hypothesis, women are likely to use alcohol for mood regulation and to help ease social relationships. The fourth is developmentally limited alcoholism, with frequent bouts of consuming large amounts of alcohol; the bouts become less frequent as persons age and respond to the increased expectations of society about their jobs and families.

Alcohol Intoxication

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for alcohol intoxication (also called simple drunkenness) are based on evidence of recent ingestion of ethanol, maladaptive behavior, and at least one of several possible physiological correlates of intoxication (Table 20.2-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree