Substance Use Disorders

Christian Hopfer

Paula Riggs

Definition

Substance use disorders (SUDs) encompass two major categories: substance abuse (SA) and substance dependence (SD). In addition, there are intoxication and withdrawal states related to specific substances. This chapter will limit its discussion to SA and SD, as these are the most common conditions encountered in child and adolescent clinical practice. SA, generally thought of as a more limited and less severe syndrome, is defined as a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment. The diagnosis of abuse cannot be made if the criteria for dependence are met. SD encompasses a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms that indicate a persistent pattern of substance use despite adverse consequences. If either of the criteria of withdrawal or tolerance to a substance is met, the diagnosis of SD is made, with the qualifier of “with physiological dependence.” Thus, to contrast the two categories, abuse involves psychosocial impairment due to substance use, but does not include physiological symptoms, persistent drug-seeking in the face of adverse consequences, or cognitive features such as being preoccupied with obtaining or using drugs. The criteria for these diagnoses are described in Table 5.8.1.

History

Use and abuse of substances have been documented throughout history and date back to ancient times. The active ingredients in substances of abuse were initially identified and extracted during the nineteenth century, leading to an increase in the purity of substances available for consumption as more concentrated formulations were made. Initially, when substances such as opiates or cocaine were first identified, they were either freely available or prescribed widely by physicians and made available through many tonics. The liability of certain substances to result in “addiction” was recognized in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when laws regulating abusable substances were introduced. The 1914 Harrison Narcotic Act, which forbade the sale of cocaine or opiates except by licensed physicians or pharmacists, was one of the first laws introduced to regulate substances seen as having a liability for abuse. Also, the widespread perception that alcohol created societal problems led to the Prohibition Amendment of 1919 to the American Constitution, which made alcohol an illegal substance. This amendment, however, was overturned in 1933.

With the creation of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics (now the Drug Enforcement Administration) in 1930 the federal government took a more active role in regulating drugs and also defining which drugs could be legally purchased, could be available only by prescription, or would be completely banned. Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, major societal changes occurred in the acceptance and use of various substances— including marijuana, tobacco, cocaine, amphetamines, and more recently, “designer” drugs such as Ecstasy.

Along with changes in societal views and consumption of various substances came an increased scientific understanding of the mechanisms of actions of most addictive compounds, including the realization that these were binding to specific brain receptor sites. Animal models of addiction established the neurobiological basis for understanding addiction as a psychiatric illness.

The psychiatric nosology of the two major substance use disorders of abuse and dependence largely evolved from epidemiological studies of adults with alcohol problems. An important question in the development of the nosology of SA or SD was whether most patients who met the criteria for abuse would go on to develop dependence and thus, whether, in effect, abuse represented a prodromal state. However, studies of adults with alcohol problems did not confirm this view, as the majority of subjects who met the criteria for abuse either continued in that category, or reported no alcohol

problems at followup, with only 11% going on to develop dependence (1,2,3). Studies of the category of SD demonstrated that it represented a more chronic relapsing condition, with the majority of adult subjects with alcohol dependence continuing to meet dependence criteria at follow-up (3,4).

problems at followup, with only 11% going on to develop dependence (1,2,3). Studies of the category of SD demonstrated that it represented a more chronic relapsing condition, with the majority of adult subjects with alcohol dependence continuing to meet dependence criteria at follow-up (3,4).

TABLE 5.8.1 CRITERIA FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND DEPENDENCE | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

For adolescents with SUDs, the question of whether those with abuse usually develop dependence remains currently unanswered. What is known is that SA is reported more commonly than SD by approximately 2:1 in adolescents (5); that in adolescence abuse and dependence may represent a single unidimensional construct (6); that polysubstance abuse is very common for adolescents with SUDs (5); and that the severity of dependence, as measured by number of dependence symptoms, predicts a poorer clinical outcome (7). Thus, the history of the development of the separate categories of abuse and dependence derives largely from studies of adults, with only limited information being available about the predictive value of these categories for adolescents.

Epidemiology

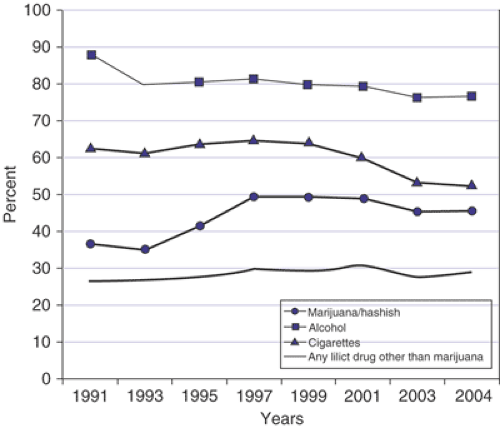

Annual surveys of U.S. adolescents’ drug use are conducted by the Monitoring the Future Survey (8). The prevalence of adolescents reporting experimenting with substances has changed over the last decade. Trends in the consumption of alcohol, marijuana, tobacco, and other illicit substances as reported by U.S. twelfth graders are shown in Figure 5.8.1. While experimentation with alcohol and tobacco declined somewhat, marijuana experimentation increased from 35% in 1991 to a peak of 50% in 1997, and then drifted down again to approximately 45% in 2004. What has remained consistent is that the most commonly used substances among adolescents are alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, with roughly a third of twelfth graders reporting lifetime experimentation with an illicit substance besides marijuana.

The frequency of substances used by general population adolescents is mirrored in admissions to substance abuse treatment facilities. Table 5.8.2 shows the substances that are listed as most common upon admission to publicly funded substance abuse treatment programs in the United States, by age category. This data is collected annually by the Treatment Episode Data Set for all publicly funded substance abuse treatment programs (9). For the youngest age group (12–14), marijuana constitutes the most frequently cited primary admitting substance of abuse. For the older (18–20) age group, marijuana and alcohol continue to represent a large portion of treatment admissions, but other illicit substances such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin are more commonly cited as reasons for admission compared with younger adolescents.

TABLE 5.8.2 PRIMARY ADMITTING SUBSTANCE OF ABUSE (% OF TOTAL ADMISSIONS), BY AGE, FROM THE TREATMENT EPISODE DATA SET | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General population surveys of adolescent substance use disorders indicate clear marked age trends. The prevalence of substance use and SUDs increases almost linearly from early to late adolescence. Approximately one in four older adolescents meets criteria for abuse for at least one substance, and one in five meets criteria for SD. Nearly one in three adolescents reports daily smoking and 8.6% meet criteria for tobacco dependence by age 18. Although alcohol is the most commonly abused substance (10%), a slightly larger proportion of adolescents meet criteria for dependence on marijuana (4.3%) than alcohol (3.5%) (10). Additionally, there are gender differences, as males report more substance use than females, and more frequently meet criteria for dependence on alcohol and marijuana in late adolescence, while females are more often nicotine dependent (10). In clinical settings rates of SUDs are high. Aarons et al. (2001) (11) reported that 62.1% of youth in juvenile justice and 40.8% of youth in mental health settings met criteria for lifetime substance use disorders.

Recent Trends in Substance Use among U.S. Adolescents

Recent surveillances of U.S. adolescents in 2004 indicate changes in patterns of substance use: Drugs that are declining in use among adolescents include marijuana and ecstasy, and amphetamine use to a lesser extent. Steroid use declined slightly from a previous peak. Drugs whose use patterns were fairly unchanged include LSD, heroin, cocaine, GHB (gamma hydroxy butyrate), and Rohypnol (flunitrazepam), as well as tranquilizers. Prescription opiates and inhalants have shown marked increases, with abuse of prescription opiates by adolescents increasing markedly over the past decade. Remarkably, roughly 10% of U.S. twelfth graders reported nonmedical use of hydrocodone, making it the third most widely abused illicit substance (after marijuana and amphetamine) among that age group (8).

Etiology

Substance use disorders can only develop if substances are available for experimentation to occur. However, despite widespread availability of many substances, only a portion of youth experiment, and only a smaller percentage of those who do experiment go on to become regular users or to develop SUDs. Thus, the etiology of SUDs lies in those factors that predispose an individual to experiment with substances, and to progress to regular use and the development of abuse or dependence.

A range of risk factors has been associated with the development of adolescent SUDs. Although a comprehensive review is beyond the scope of this chapter, major theories about the etiology of adolescent SUDs will be covered. See Whitmore and Riggs (2006)(12) for a more complete review.

Genetic and Environmental Influences

Twin and adoption studies have demonstrated that considerable shared environmental influences exist for the initiation of substance use, and that genetic influences become more apparent when environments allow for their expression (13). Thus, for example, Koopmans et al. (14) demonstrated that there were no genetic influences on the liability to initiate alcohol use when adolescents were raised in a religious household, but that 40% of the variation in initiation could be explained by genetic factors when adolescents were raised in a nonreligious household. Genetic influences on the development of adolescent SUDs may act through a direct effect on psychophysiological reactions to substances or their metabolism, or indirectly through genetic effects on personality traits such as behavioral disinhibition, which leads to substance experimentation (15). Thus, genetic factors influence individual risk, but do not account for population-wide shifts in patterns of substance use. A strong family history of SA or SD is a strong predictor for who goes on to initiate substance use or develop SUDs.

Externalizing Disorders

Externalizing disorders have been shown to be major risk factors predicting the initiation of substance use and the development of abuse and dependence [reviewed by Crowley and Riggs, 1995 (7)]. Many of the risk factors associated with the development of externalizing disorders similarly predispose to the development of substance use disorders. Conduct disorder has consistently been shown to be a predictor of substance use initiation and progression toward SUDs. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) appear to increase risk for developing SUDs somewhat, although there is controversy about the magnitude of the effect of ODD or ADHD due to their comorbidity with CD. Externalizing disorders and SUDs can also be thought of as influenced by a single underlying factor, as posited by problem behavior theory (16).

Stage Theory and the “Gateway” Theory

Stage theory posits that there is a temporal ordering of substance experimentation in which lower order substances, which are more commonly used, precede the use of higher order substances. Thus, typically a licit substance, such as alcohol or cigarettes, is used first in a sequence, followed by marijuana, which is usually the first illicit substance before progressing on to use of other illicit substances (17). Related to stage theory is the gateway hypothesis as it relates to marijuana: This posits that the use of marijuana facilitates the entry into other illicit substance use.

A review of the available literature about the effect of marijuana use on other drug use concluded that there is a relationship between marijuana use and progression to other drugs. This effect can be explained by 1) the selective recruitment to heavy cannabis use of persons with preexisting traits that predispose to the use of a variety of different drugs (i.e., that marijuana use is a marker for a tendency to use multiple drugs); 2) the affiliation of cannabis users with drug-using peers in settings that provide more opportunities to use other illicit drugs at an earlier age; and 3) that marijuana use results in socialization into an illicit drug subculture which creates favorable attitudes toward the use of other illicit drugs (18).

Early Onset of Use

Early onset of substance use has been shown to be a strong predictor for the development of substance use disorders over the lifetime (2). Whether this is due to early use being a marker for other risk factors that predict substance involvement or whether it has a causal effect is unknown. Recent animal work has suggested that the adolescent brain may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of drug sensitization, providing a possible neurobiological explanation for the increased incidence of substance use disorders among those who begin drug use early (19).

Family and Peer Effects

Substance use disorders tend to aggregate in families. This may be in part due to some common genetic influences within families; however, there is substantial evidence of environmental mediation. Parental drug use, as well as drug use by older siblings, is a significant risk factor for the development of adolescent substance use. However, the mechanism of transmission is complex, with individual personality dimensions mediating the effect of sibling and parent influences (20,21).

Association with delinquent peers has been one of the hallmarks of the development of adolescent substance use disorders. However, while the common notion has been that peers create “peer pressure” to consume substances, most studies support the notion that there exists a complex process by which individuals select peer groups, and then in turn influence these, as well as are influenced by them (22).

Biological Mechanisms in the Etiology of Substance Use Disorders

A large body of animal work has shown that repeated exposure to substances leads to neural adaptations altering the hedonic “tone” of individuals. This tone is reset by substance use so that it is lower over time, resulting in dysphoria and craving when not using, and driving the substance dependence cycle (23). This animal work has been key in demonstrating that all substances of abuse, although acting at different receptors, create a common downstream pathway resulting in neural adaptations that perpetuate the addictive cycle.

Substance-Specific Risks

Although all substances share common neurologic pathways that are involved in the development of substance use disorders, there are differences between substances in terms of their addictive potential. The time course toward the development of dependence varies by individual, by substance, and by route of administration. Some substances, such as cocaine, are characterized by a rapid onset of the development of dependence, as for example 6 % of cocaine users develop dependence within one year of experimenting with cocaine (24). In a longitudinal study, Wagner and Anthony (25), for example, demonstrated that whereas some 15–16% of cocaine users had developed cocaine dependence within 10 years of first use, the corresponding values were about 8% for marijuana users, and 12–13% for alcohol users.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

The diagnosis of SA or SD is made primarily through the clinical interview with the adolescent, as well as through obtaining collateral information from parents and teachers. Adolescents are likely to be in a “precontemplative” stage of change and may thus minimize the extent of their substance involvement (26). Establishing rapport with the adolescent is critical in order to increase the chance of self-disclosure of drug use. Early strong therapeutic alliance is facilitated by use of motivational interviewing (MI) style which is characterized by a nonjudgmental, collaborative approach.

Of primary clinical concern is the extent or severity of substance involvement, the specific substances that the patient is abusing or dependent on, and the length of time that the pattern has persisted. When an MI approach is taken and the limits of confidentiality are carefully explained to adolescents and parent/guardians, clinicians are much more likely to get an honest history of substance severity along with other behavioral problems.

When conducting an initial assessment with an adolescent for substance use disorders, the parents or caretakers should ideally be present at the initial interview. This allows the establishment of the rules of confidentiality (including that reports of abuse, neglect, or threats of harm to self or others must be disclosed). In order to optimize therapeutic alliance with adolescent patients and to enhance validity of clinical information, it is recommended that the adolescent’s confidentiality be honored, unless specific permission and release is obtained or unless the patient is clinically judged to be a danger to self or others. Adolescents may be more willing to self-disclose if the rules of confidentiality are clearly established at the beginning of treatment. But the exceptions to confidentiality should be specified at the beginning of treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree