Suicide and attempted suicide in children and adolescents

David Shaffer

Cynthia R. Pfeffer

Jennifer Gutstein*

Introduction

Suicidal behaviour is a matter of great concern for clinicians who deal with the mental health problems of children and adolescents. The incidence of suicide attempts reaches a peak during the midadolescent years, and mortality from suicide, which increases steadily

through the teens, is, in many countries, one of the leading causes of death at that age.

through the teens, is, in many countries, one of the leading causes of death at that age.

Historical review

Until the late 1950s, knowledge about youth suicide was drawn from unrepresentative case reviews, reviews of the demography of suicide drawn from death certificate data, and speculation about dynamics. The late 1950s saw the first systematic psychological autopsy study among adults that demonstrated the importance of psychiatric disorder as a proximal cause of most suicides.(1) This was followed by similar studies on children and adolescents,(2,3,4,5) confirming the association in adolescence. Starting in the mid-1960s, the incidence of suicide in young males began to rise in many countries.(6) The rate of increase eventually stabilized in the late 1980s and, in many countries, is now showing signs of falling.(7) These changes stimulated efforts to develop methods of preventing youth suicide.(8,9,10,11).

A good deal is now known about which teenagers commit suicide, less about who attempts it, and very little about the optimal management of suicidal adolescents. The number of randomized controlled trials designed to assess different forms of treatment is exceedingly small, and many suggestions for clinical management are based on anecdotal accounts rather than on findings from well-designed experimental trials.

Clinical features

Completed suicide

Completed suicide occurs most commonly in older adolescents, and, although it can also occur in children as young as 6 years of age, it is excessively rare before puberty.(7) Psychological-autopsy studies have shown that about 90 per cent of adolescent suicides occur in individuals with a pre-existing psychiatric disorder, often present for several years.(3,4,5) In teenagers, the most common disorders are some form of mood disorder, substance and/or alcohol abuse, often comorbid with a mood disorder in boys over age 15, and anxiety disorders.(3, 4) At a trait level, many suicide completers have been noted to be irritable, impulsive, volatile, and prone to outbursts of aggression. However, this pattern of behaviour is by no means universal, and anxious suicides have usually shown no evidence of prior behavioural, academic, or social disturbances.(3)

Although some adolescents—predominantly girls suffering from a major depressive disorder—appear to have thought about suicide for some time before death, most adolescent suicides appear to impulsively follow a recent stress event, such as getting into trouble at school or with a law-enforcement agency; a ruptured relationship with a boy- or girlfriend; or a fight among friends. In many instances, these stress events can be seen as a by-product of their underlying psychiatric disorder.(12)

It also appears that a completed suicide can be precipitated—in a presumably already suicidal youth-by exposure to news of another person’s suicide, or by reading about or viewing a suicide portrayed in a romantic light in a book, magazine, or newspaper.(13)

About a third of completed suicides have made a previous known suicide attempt, more commonly girls and those who suffered from a mood disorder.(3) Completed suicide must be distinguished from autoerotic asphyxia, which is rare in teenagers.(3) Suicide pacts, common between middle-aged or elderly married couples and/or other family members, are similarly rare in adolescents, but are not unknown.(3)

Non-lethal suicidal behaviour

(a) Suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation includes thoughts about wishing to kill oneself, making plans of when and where, and having thoughts about the impact of one’s suicide on others. Such thoughts may occur without great significance among young children, who may not appreciate that suicide may result in irreversible death.(14) However, appreciation of the finality of death should not be a factor in judging the seriousness of suicidal ideation. Suicide threats made by young children and adolescents most often involve a threat to jump out of a window, to run into traffic, or to stab himself or herself.

(b) Attempted suicide

The most common profile of a teenaged attempter is a 15- to 17-year-old girl who has taken a small- or medium-sized overdose of an over-the-counter analgesic or medication taken by another family member. The behaviour is usually impulsive and occurs in the context of a dispute and humiliation with family or a boyfriend.(15) The clinical features most strongly associated with suicide attempts are irritability, agitation, threatening, violent, or psychotic behaviour, and a persistent wish to die.(16)

Groups in whom suicide attempts appear to be common include runaways,(3) children who have been exposed to physical and sexual abuse, and homosexual teenagers.(17) However, study-design issues make it unclear whether this is because of a high rate of psychopathology or substance abuse in these groups or because of some factor that specifically predisposes to suicidal behaviour.

A subset of non-fatal suicidal behaviour involving ingestion with a non-lethal intent is sometimes referred to as parasuicide. However, intent is difficult to gauge retrospectively, and not all teenagers are aware of the lethalness of an ingestion, so that this term carries with it a risk of complacency and is probably best avoided in teenagers.

Assessment

Suicide attempts

Assessment of a suicide attempt involves an evaluation of the short-term risk for suicide and attempt repetition, and an assessment of the underlying diagnosis or other promoting factors. If the child or teenager has been referred to as an ideator, it is important to determine whether they are contemplating or have secretly attempted suicide.

Repeated attempts, attempts by unusual methods (other than ingestions or superficial cutting), medically serious attempts, and attempts where the patient has taken active steps to prevent discovery all increase the risk for further attempts or death.(18,19) Children and adolescents systematically overestimate the lethality of different suicidal methods, so that a child with a significant degree of suicidal intent may fail to carry out a lethal act.(20,21,22)

The mental states leading to suicidal behaviour include anticipatory anxiety, pessimism, or hopelessness, as well as paranoid or other cognitive distortions arising from an underlying psychiatric diagnosis.(23) Inappropriate coping styles (e.g. impulsivity or catastrophizing) in response to external stress may also contribute to the behaviour. Motivating feelings may include the wish to effect a change in interpersonal relationships, to rejoin a dead

relative, to avoid an intolerable situation, to get revenge, or to gain attention.(22)

relative, to avoid an intolerable situation, to get revenge, or to gain attention.(22)

Classification of associated diagnoses

Suicide

Psychiatric diagnoses commonly associated with a suicide include depression, bipolar disorder, substance abuse, conduct disorder, and overanxious and panic disorders.(3,4,5) Although the rate of suicide in schizophrenics is high, because of the rarity of the condition, it accounts for very few suicides.

Suicide attempts

Recurring suicidal behaviour has been associated with hypomanic personality traits and cluster B personality disorders.(22) A history of impulsivity, mood lability, with rapid shifts from brief periods of depression, anxiety, and rage to euthymia and/or mania—associated with transient psychotic symptoms, including paranoid ideas and auditory or visual hallucinations-is associated with a risk for further suicide attempts and is compatible with the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Many of these symptoms are also features of bipolar mood disorder.

Epidemiology

Completed suicide

(a) Age

In the United States, the age-specific mortality rate from suicide for 10- to 14-year-olds was 1.6 per 100 000 in 1997.(24) This age group accounts for 7 per cent of the population but only 1 per cent of all suicides, and most of these occur in 12- to 14-year-olds.

The comparable figures for 15- to 19-year-olds are about six times higher. The suicide rates at this age in the United States and Canada in 1997 were 9.5 per 100 000 and 12.86 per 100 000 respectively.(7) The proportion of suicides that occur in this age group is about the same as its representation in the general population.

Suicide rates for 15- to 24-year-olds in some other English-speaking countries were 11.0 for males and 2.2 for females in the United Kingdom (1995), 16.0 in Australia (1995), and 26.1 in New Zealand (1997) (all per 100 000 population).(7)

(b) Gender

In the United States and most other countries, male suicides outnumber female suicides among 15- to 24-year-olds by a ratio of 4:1. In China and Cuba, the suicide rate is higher in females than in males.(7)

(c) Cultural and ethnic differences

Rates of suicide vary considerably in different cultural and national groups.(7) Possible reasons include variable access to lethal methods, different degrees of social support, integration, or group adherence, or the influence of religious beliefs or spirituality.(25,26,27) In some instances, the differences may be a function of geography rather than culture. Contagion within isolated groups may determine differences in rates.

(d) Secular changes

From 1964 to 1995, the suicide rate in the United States and Canada among 15- to 19-year-old males increased almost three-fold, and similar increases were reported in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.(7) In most of these countries, there was little change in the female rate or in the rate amongst 10- to 14-year-olds. Fluctuations in the suicide rate appear to be real, rather than due to any methodological artefact (e.g. changes in reporting practices). The most plausible reason for the increase in suicidal behaviour among teenage boys is an increase in alcohol and substance use in the youth population.(3) The reasons offered for the recent decline in suicide rates include lowered substance- and alcohol-use rates among the young and more effective diagnosis and treatment.(28)

Attempted suicide

There is a strong inverse relationship between attempted suicide and age. A large epidemiological survey of four suicide-related behaviours (ideation, plan, gesture, and attempt) in the United States has shown a significantly higher rate of all four behaviours in the youngest age group (15-24 years).(29) This study also compared rates of these four behaviours across two decades (1990-1992 and 2001-2003). It found that rates did not decrease, despite a dramatic increase in pharmacologic treatment.

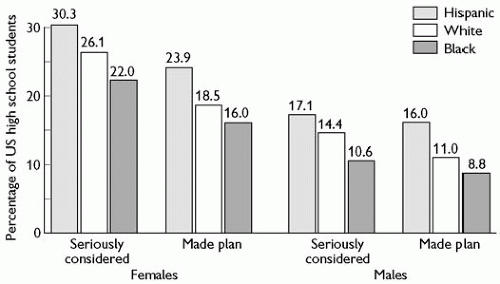

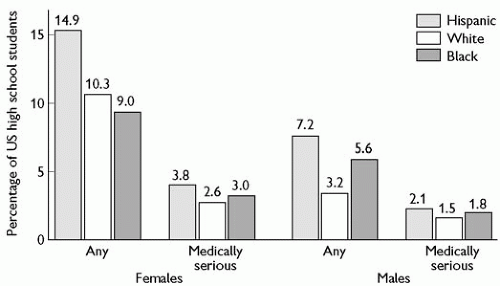

Suicide attempts in adolescents are at least twice as common in females as males (see Figs 9.2.10.1 and 9.2.10.2). Considerable ethnic variation is seen in the United States, with, for unknown

reasons, Hispanic high-school students having twice the rate of black or white teenagers.(30)

reasons, Hispanic high-school students having twice the rate of black or white teenagers.(30)

Aetiology

Completed suicide

(a) Psychiatric disorders

The most important risk factor for suicide is a psychiatric disorder.(3) Controlled studies of completed suicide suggest similar risk factors for boys and girls,(3, h31) but with marked differences in their relative importance(3,4,5) (Table 9.2.10.1). In girls, major depression is the most powerful risk factor, which, in some studies, increases the risk of suicide 12-fold; followed by a previous suicide attempt, which increases the risk approximately three-fold. In boys, a previous suicide attempt is the most potent predictor, increasing the rate over 30-fold. It is followed by depression (12-fold increase), disruptive behaviour (two-fold increase), and substance abuse (increasing the rate by just under two-fold).(3)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree