Supplementary Sensorimotor Epilepsy

Introduction

As discussed in Chapter 3, frontal lobe epilepsy presents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to clinicians, particularly as it refers to patients with medically refractory seizures arising from the frontal lobe. There is a bizarre and unfamiliar semiology that can present with frontal lobe epilepsy—at times this can bring into question whether the patient in fact has epilepsy or psychogenic seizures. Seizures arising from the mesial frontal lobe or within the supplementary sensorimotor area (SSMA) are of particular interest because patients may be well aware of their surroundings during what appears to be a generalized motor seizure. Typically, one would expect consciousness to be impaired during such a seizure but in cases of SSMA seizures, consciousness may be retained. Seizures arising from areas near or adjacent to the SSMA, such as the mesial frontal lobe, often propagate quickly to the SSMA, displaying SSMA seizure semiology; therefore, a minority of these patients with SSMA seizures actually have supplementary sensorimotor epilepsy (SSME). SSME is rare, with an incidence among epileptics undergoing video-electroencephalography (video-EEG) monitoring to be as low as 2.0%. It can be lesional or non-lesional with a broad array of aetiologies, including cortical dysplasia, encephalomalcia and idiopathic aetiologies. It usually presents with ambiguous EEG abnormalities, if with any, and with scalp EEG it is difficult to correctly localize. In cases of medically refractory SSME, particularly those associated with a lesion a surgical resection may yield a good outcome with only a transient neurological deficit. However, proper identification of the epileptogenic zone is of prime importance as in all cases of surgical treatment for epilepsy, but the recognition of involvement of the SSMA region might yield clues as to its correct location. Astute and careful clinical practice is required to correctly identify and treat this epilepsy, which can be so easily mistaken for another syndrome.

Anatomy of the supplementary sensorimotor area

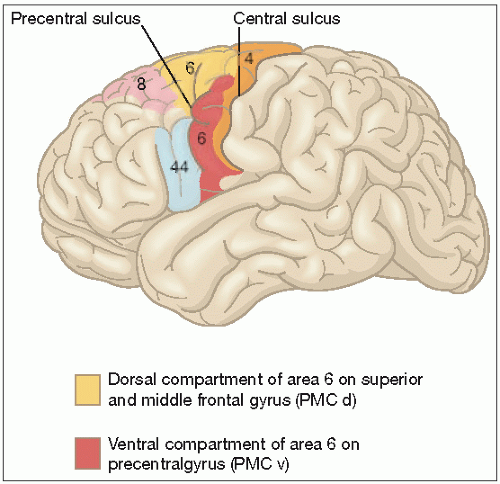

Classically the frontal motor cortex is divided functionally into the primary, premotor, and supplementary motor regions. The SSMA occupies the medial and superolateral portion of Brodmann’s area 6. It represents the body topographically, with the head located in the anterior portion and the legs and the feet in the posterior part, adjacent to Brodmann’s area 4. It has complex reciprocal connections with the lateral frontal cortex. The corpus callosum also joins homotopic areas of both the SSMA on both hemispheres. Other afferents include input from the basal ganglia (globus pallidus and pars reticularis of substantia nigra). It receives both proprioceptive and cutaneous afferents from the ventral posterosuperior nucleus and the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus.

Cortical stimulation elicits more complex motor responses in the SSMA when compared with the primary motor cortex with a greater threshold for responses to electrical stimulation. Corticospinal projections from the SSMA terminate principally on spinal interneurons and not directly on lower motor neurons. It should also be noted that SSMA afferents drive upper motor neurons in the primary motor cortex (4.1).

Seizure semiology

Seizures arising from the SSMA have a distinctive ictal semiology that may allow a provisional diagnosis to be made on

review of clinical history alone (Table 4.1). Seizures have been noted to be extremely brief, lasting between 10 and 40 seconds only. They usually begin abruptly without warning and manifest directly with motor phenomena. Asymmetric posturing involving the extremities bilaterally usually marks the onset. Unilateral tonic motor activity may also occur, although it is not as frequent. The shoulders are usually elevated and the arms abducted with some flexion of the elbows. The lower limbs may also show abducted hips with knees either extended or semi-flexed. It has been reported that all four extremities are tonically postured, however, asymmetrically. During the ictal semiology consciousness may be preserved, so that during the tonic phase of this seizure the patient may appear to attempt to move body position, such as trying to sit up straight or may display writhing truncal movements. Orofacial and gestural automatisms are absent; however, patients may display coarse, uncoordinated movements of their tonically postured limbs. Bizarrely, asynchronous use of all four limbs with preservation of consciousness may lead to the misdiagnosis of psychogenic seizures, observing tonically abducted arms combined with open eyes, predominant nocturnal occurrence and the brevity of the seizure is useful in distinguishing a SSMA seizure from a psychogenic seizure.

review of clinical history alone (Table 4.1). Seizures have been noted to be extremely brief, lasting between 10 and 40 seconds only. They usually begin abruptly without warning and manifest directly with motor phenomena. Asymmetric posturing involving the extremities bilaterally usually marks the onset. Unilateral tonic motor activity may also occur, although it is not as frequent. The shoulders are usually elevated and the arms abducted with some flexion of the elbows. The lower limbs may also show abducted hips with knees either extended or semi-flexed. It has been reported that all four extremities are tonically postured, however, asymmetrically. During the ictal semiology consciousness may be preserved, so that during the tonic phase of this seizure the patient may appear to attempt to move body position, such as trying to sit up straight or may display writhing truncal movements. Orofacial and gestural automatisms are absent; however, patients may display coarse, uncoordinated movements of their tonically postured limbs. Bizarrely, asynchronous use of all four limbs with preservation of consciousness may lead to the misdiagnosis of psychogenic seizures, observing tonically abducted arms combined with open eyes, predominant nocturnal occurrence and the brevity of the seizure is useful in distinguishing a SSMA seizure from a psychogenic seizure.

During the tonic phase of the seizure, speech arrest occurs slightly more frequently than vocalization. Vocalizations take the form of the patient crying out or moaning loudly and intelligible speech is extremely rare. Some vocalizations may be due to the involuntary contraction of the diaphragm or the laryngeal muscles, and, in others, they appear to be emotional responses to their awareness of seizure onset. The tonic phase is then followed by a clonic phase during which one or more extremity move in a rhythmic or clonic manner. Versive head movements often occur prior to secondary generalization and serve as a reliable lateralizing sign in this setting, lateralizing to the contralateral hemisphere. Seizures tend to occur in clusters, and as many as five to 20 per day have been observed in patients with intractable SSMA epilepsy and thus can be very disabling.

Electroencephalography in supplementary sensorimotor epilepsy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree