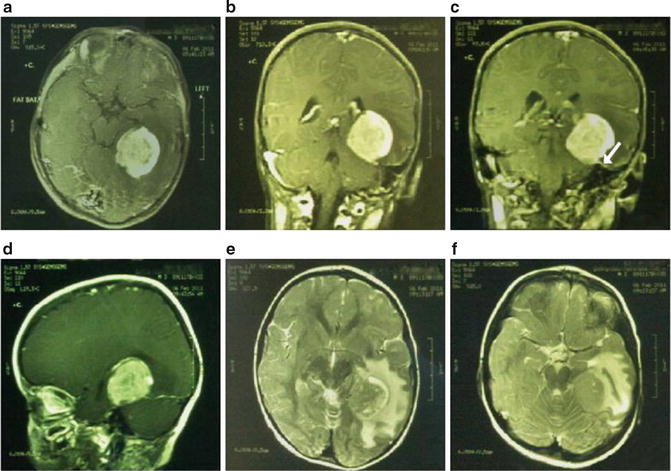

Fig. 8.1

MRI study of a 28-year old male with pineoblastoma. (a) Axial CT scan without contrast: The sharply demarcated tumor is hyperdense in CT images. Hydrocephalus is also evident. A small portion of the tumor is strongly hyperdense representing calcification. (b) and (c) Axial T1-weighted without contrast and FLAIR MRI: The tumor is isointense to cortical parenchyma in T1 and hyperintense in FLAIR. Again signs of hydrocephalus are visible. (d) Axial T1-weighted with contrast: The lesion is homogenously enhanced with gadolinium administration

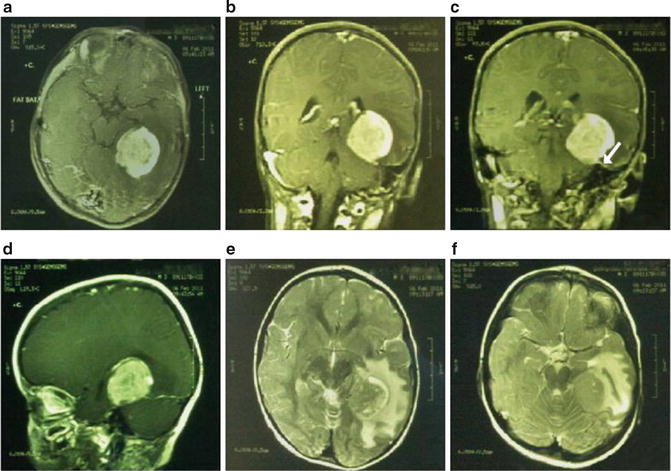

On MRI scans, the tumors are usually isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted images, isointense or hyperintense on T2-weighted images, and strongly enhancing after gadolinium injection (Figs. 8.1, 8.2 and 8.3). Usually, there is a relatively good demarcation between the borders of the tumor and the adjacent brain tissue (Dai et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2002). Approximately 11% of supratentorial PNETs are not contrast enhancing on an MRI scan (Johnston et al. 2008). This makes postoperative assessment of residual disease more difficult. Intra- and peri-tumoral hemorrhage can be noticed in 12–37% of the cases (Dai et al. 2003; Johnston et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2002). Radiologic signs of necrosis can also be visualized in some cases (Kim et al. 2002). Lepto-meningeal involvement does not preclude the diagnosis and can be discovered in 18% of cases (Johnston et al. 2008). Non-pineal supratentorial PNETs may be firmly attached to the dura misleading to the diagnosis of an extra-axial tumor (Fig. 8.3). The evidence seems to be conflicting regarding the amount of peri-tumoral edema. Dai et al. (2003) and Klisch et al. (2000) believe that presence of significant vasogenic peri-tumoral edema is very unusual in these tumors, while Kim et al. (2002) report it to be present in almost every case in adults. Solid portions of the supratentorial PNETs are usually hyperintense in diffusion-weighted images (DWI) of MRI mainly due to high cell density (Klisch et al. 2000).

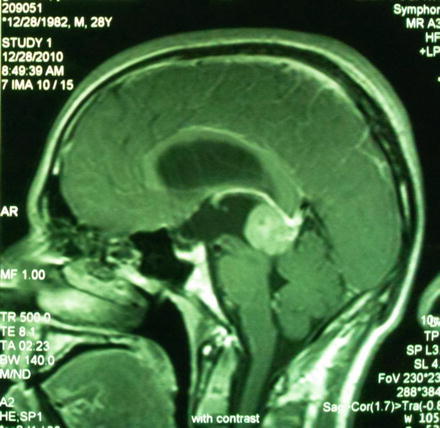

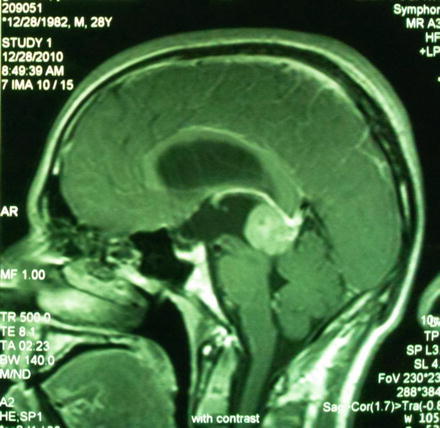

Fig. 8.2

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI with contrast of the same patient discussed in Fig. 8.1: The tumor is located at the posterior border of third ventricle, superior to the quadrigeminal plate proposing a lesion arising from pineal gland and enlarging this structure. Tri-ventricular hydrocephalus is evident

Fig. 8.3

MRI study of a 3-year old boy with ependymoblastoma. (a) Axial Fat Sat image with contrast: The supratentorial tumor has a well- defined border with the adjacent parenchyma and is homogenously enhanced with gadolinium administration. (b), (c), and (d) Sagittal and coronal T1-weighted MRI with contrast: The tumor seems to have a base on the tentorium and a dural tail along its surface (shown with the white arrow) resembling a tentorial meningioma. This dural tail is actually believed to be a sign of tumor aggression and malignancy. (e) and (f) Axial T2-weighted MRI: Significant surrounding edema exists around the borders of the tumor

In summary, supratentorial PNETs should be kept in the list of differential diagnosis when a large hyperdense supratentorial tumor with sharp margins is discovered.

Because PNETs can spread throughout the CNS, many physicians obtain MRI scan of the spine as soon as the diagnosis of PNET is entertained. Postsurgical blood and protein may confound spinal imaging for weeks after surgery, therefore preoperative spinal MRI may give the best assessment of spinal metastasis. At the time of diagnosis, MRI of the spine is reported to be normal in 88–100% of supratentorial PNETs (Johnston et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2002). In angiographic evaluations, focal areas of prominent vascularity are frequently seen (Kim et al. 2002). On Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) examinations, choline increases in these tumors. The amount of choline is significantly more than low grade and anaplastic astrocytomas, glioblastomas, and metastases (Majos et al. 2002).

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

PNETs often seed within the central nervous system (CNS) via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). These tumors may be multicentric at the time of diagnosis. In the Children’s Cancer Group study, metastatic spread at the time of diagnosis was found in 19% of supratentorial PNETs (Cohen et al. 1995). Dirks et al. (1996) reported a 38.9% rate of intracranial or spinal dissemination at the time of diagnosis. Other investigators reported a rate ranging from 7 to 12% for spinal seeding in supratentorial PNETs (Yang et al. 1999). Accordingly, CSF analysis can be helpful, if not mandatory, in the primary assessment; in order to discover any metastatic dissemination of these tumors into CNS. CSF analysis is reported to be positive for malignant cells in 9% of the cases (Johnston et al. 2008).

Bone Marrow Analysis and Bone Scan Analysis

Supratentorial PNETs may even metastasize beyond neuraxis. However, systemic metastases are not frequent, and usually occur at the time of recurrence (Jakacki 1999; Yang et al. 1999). Thus, for the newly diagnosed cases of supratentorial PNETs, preoperative bone marrow analysis and bone scans may be unnecessary and are no longer recommended as part of the staging process, unless clear symptoms and signs of involvement of other locations exist (Johnston et al. 2008).

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is a crucial part of treatment in these tumors and is beneficial for both diagnosis and decompression. Nevertheless, total resection is not always possible in these cases. The preoperative administration of corticosteroids appears to help the surgeon by decreasing the amount of peritumoral edema and ICP. Their preoperative use for at least 24–48 h appears to improve the whole clinical and neurological status of the patient. Similarly, pre-and intraoperative administration of anticonvulsant agents can be helpful for these tumors.

Standard neurosurgical and anesthetic techniques should be used in the removal of these tumors. Careful monitoring of urine output through a Foley catheter is recommended. Since these can be vascularized tumors, transfusion may be necessary. Accordingly, adequate venous access as well as arterial pressure monitoring is important. This is particularly required in young children in whom the amount of blood loss can be significant and may limit the extent of resection. Doppler cardiac monitoring is also required when the head is positioned significantly higher than the heart. Hence, placement of a CV line is strongly proposed in such cases. Air embolism must be considered if there is a sudden decrease of end-tidal PCO2 or a drop in O2 saturation.

These tumors are generally purplish gray or pinkish lobulated neoplasms with well demarcated borders along the adjacent normal brain in the majority of cases (Kim et al. 2002). Debulking of the tumor can allow the surgeon to bring in the edges of the lesion to better identify the margins of it. Gross total resection of the tumor is the optimal goal of surgery, but it must be balanced against potential neurological deficits particularly when there is adjacency to eloquent locations. Complete resection can be achieved in only 33–58% of the cases (Johnston et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2002; Timmermann et al. 2002) and as usual, surgeons most familiar with these tumors achieve the greatest amount of resection. The wide involvement of the brain and increased vascularity of these tumors are the main reasons precluding total or radical excision. Use of an ultrasonic aspirator greatly enhances the speed of tumor removal and assists with reducing blood loss. When the tumors are in the vicinity of eloquent regions, performing awake surgeries is another option. Also, surgical approach can be tailored according to preoperative diffusion tensor (DTI) images and concomitant use of neuronavigation. Additional surgical interventions may be needed when there is local recurrence. Stereotactic radiosurgery is another option when the local recurrence is not voluminous (Kim et al. 2002).

Complications

Hemorrhage in the tumor bed, brain edema, and new neurological deficits such as hemiparesis are some of the reported complications of surgery (Kim et al. 2002). Cerebrospinal dissemination can be a potential complication of surgical manipulation of these tumors but the reported incidence of this phenomenon is negligible (Kim et al. 2002). In the modern era, the rate of operative mortality is very low (Jakacki 1999; Kim et al. 2002).

Postsurgical Assessments

Determination of residual disease is best done by MRI performed within 24–48 h after surgery, before any enhancement attributable to postoperative inflammation or gliosis can cloud the imaging of residual neoplasm. Cytologic examination of CSF can also be performed by lumbar puncture about 2 weeks after surgery, after sufficient time has passed to avoid contamination by operative debris. Similarly, intraoperative samples may be taken at the beginning of the procedure. A CSF cytology determination that is positive for tumor cells, either preoperatively or postoperatively, predicts a poor outcome. A negative cytology test, however, does not preclude advanced disease. Spinal MRI should be done after surgery if it was not already performed. Postoperative imaging can occasionally be difficult because of the presence of postoperative debris and blood.

Outcomes and Adjuvant Therapy

Despite the concomitant use of hyperfractionated craniospinal radiation and adjuvant chemotherapy in the postoperative period, survival is generally poor in supratentorial PNETs particularly in children (Johnston et al. 2008). Local recurrence and CSF dissemination are chief causes of such a poor outcome. Current data suggest that children diagnosed with supratentorial PNETs have a poorer median survival interval than children with infratentorial medulloblastomas (Nishio et al. 1998a; Packer and Finlay 1996; Paulino and Melian 1999; Reddy et al. 2000). It is possibly because of younger age at time of diagnosis and special considerations for radiotherapy or frequent dissemination of such tumors (especially pineoblastomas) in the earlier phase of the disease. The 4-year survival of these tumors is also reported to be 37.7% in children (Johnston et al. 2008). Accordingly, most of the management protocols have included these patients within treatment regimens designed for children with poor-risk medulloblastoma. The prognosis is usually better for adults (Paulino and Melian 1999; Terheggen et al. 2007), in whom the mean survival is as high as 86 months and 3-years survival is 75% (Kim et al. 2002). Another important related issue in the management of PNETs is the quality of life among long-term survivors. It is now well recognized that a significant number of long-term surviving children have noticeable neurocognitive, endocrinologic, and psychological sequelae (Packer and Finlay 1996). However, this does not seem to be true among adults. The karnofsky performance scales (KPS) in the adult survivors is generally more than 70 with the mean follow-up duration of 49 months (Kim et al. 2002).

There is a paucity of articles discussing the prognostic factors of supratentorial PNETs.

Some factors have been proposed as being consistently important for outcome including: adjuvant therapy, age at the time of diagnosis, extent of initial resection, evidence of metastatic disease, histopathology, proliferation markers, and site of tumor. The impact of most of these factors on the outcome is highly controversial and the true prognostic effect of each is yet to be recognized:

Adjuvant therapy: Although the survival is poor in general, it can be prolonged with chemotherapy and radiation therapy in children (Jakacki 1999; Johnston et al. 2008; Yang et al. 1999) and adults (Terheggen et al. 2007). According to some reports radiotherapy is even more advantageous compared to chemotherapy (Nishio et al. 1998a; Paulino and Melian 1999; Timmermann et al. 2002). Radiotherapy is especially beneficial when it can be tolerated in pineal PNETs, which are somewhat resistant to chemotherapy in infants and young children (Hinkes et al. 2007; Jakacki 1999). Nevertheless, contradictory results can also be found in literature. There are several investigators who could not find any statistically significant benefit attributed to chemotherapy in children (Tomita et al. 1988) or adults (Kim et al. 2002) suffering from supratentorial PNETs. It seems that long-term survival rates with adjuvant chemotherapy, however, is much higher in recent reports than the previous ones, especially when high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell rescue is used (Broniscer et al. 2004; Butturini et al. 2009; Fangusaro et al. 2008; Gururangan et al. 2003; Perez-Martinez et al. 2004, 2005; Sung et al. 2007).

Age at the time of diagnosis: Largest series on PNETs have reported improved survival rates when these tumors are seen in older children and adults. Young age (less than 3 years of age) has been consistently shown to have an adverse effect on prognosis of these patients (Albright et al. 1995; Dirks et al. 1996; Hinkes et al. 2007; Jakacki 1999; Johnston et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2002). But among adults, age at the time of diagnosis does not seem to have any significant relation to outcome (Kim et al. 2002).

Extent of initial resection: Although radical resection, if possible, is suggested by the majority of the investigators, the effect of gross total or radical resection on the outcome is not clear. Nishio et al. (1998a) proposed such a beneficial effect in their review of literature. Albright et al. (1995) reported improved survival, albeit not statistically significant due to small sample size, for the patients in whom postoperative residual tumor was measured less than 1.5 cm2. Yang et al. (1999) found a statistically significant relationship between the extent of surgery and the outcome in univariate analysis but they failed to show such a relationship in the multivariate analysis. However, more recent reports could not find any relationship between the extent of surgery and outcome either in children (Johnston et al. 2008) or adults (Kim et al. 2002).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree