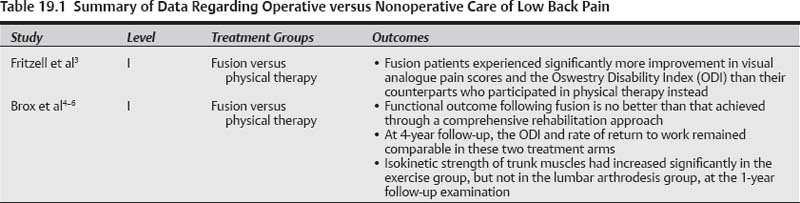

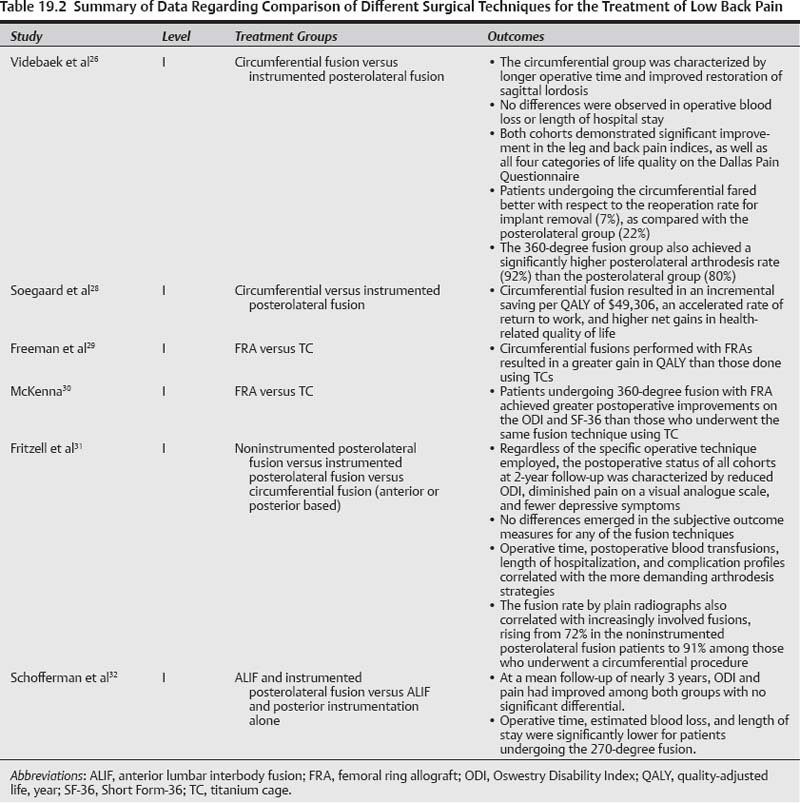

19 Broadened application of lumbar fusions in treating chronic low back pain has caused such procedures to proliferate rapidly.1,2 Despite its ubiquity, however, the level I evidence supporting arthrodesis per se remains both controversial and scant. This evidence originates from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group3 and a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial4,5 performed at four Norwegian hospitals. Fritzell and colleagues3 demonstrated that 222 patients who underwent operative treatment consisting of one of three fusion techniques experienced significantly more improvement in visual analogue pain scores and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) than their 72 counterparts who participated in physical therapy instead. The inclusion criteria limited trial entry to those patients who presented with low back pain more pronounced than leg pain, persisting longer than 2 years, refractory to a course of conservative treatment, and with no evidence of nerve root compression. Conversely, the prospective study of Brox et al4 from Norway suggests that functional outcome following fusion is no better than that achieved through a comprehensive rehabilitation approach. These investigators randomized 64 patients with low back pain lasting beyond 1 year in the setting of L4–L5 and/or L5–S1 disk degeneration and 60 additional patients with postlaminectomy syndrome. The operative treatment arm consisted of a posterolateral fusion with transpedicular screws and postoperative physical therapy. The nonoperative treatment arm corresponded to a modern rehabilitation protocol initiated by an education intervention and a 3-week course of intensive exercise sessions, based upon cognitive-behavioral principles. At 4 years’ follow-up, the ODI and rate of return to work remained comparable in these two treatment arms.5 The Norwegian trial further found that isokinetic strength of trunk muscles had increased significantly in the exercise group, but not in the lumbar arthrodesis group, at the 1-year follow-up examination.6 Several distinct surgical strategies for accomplishing a circumferential (i.e., 360-degree) fusion have emerged: staged anterior and posterior fusion (APF), posterior lumbar inter-body fusion (PLIF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), and anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF). Inter-body fusions stabilize the anterior column and maintain disk space height, while restoring coronal and sagittal balance.7 The increased vascularity of the interbody space in comparison to the posterolateral space fosters formation of a solid fusion mass. Biomechanical stability of interbody constructs is derived from the posterior spinous ligaments, facet, and anulus acting as tension bands—with the graft placed under compression in accordance with Wolff’s law.8 In the 1940s, initial descriptions of the PLIF procedure depended upon the use of laminectomy bone chips9 and excised portions of the spinous process10 as interbody grafts. In 1953, Cloward11 reported on a modified PLIF performed using autogenous iliac crest bone graft (ICBG) within the disk space. Because PLIF requires retraction of the thecal sac and nerve roots to allow access to the posterior disk space, the risk of iatrogenic neuropraxia, radiculitis, endoneural fibrosis, incidental durotomy, epidural fibrosis, and injury to the conus medullaris remained high for a Cloward’s modification as well. The TLIF procedure, first set forth by Harms,12 is a PLIF variant that involves a unilateral total facetectomy to allow posterolateral extracanalar diskectomy and foraminal decompression. By sparing the contralateral pars, facet, and lamina, surface area is preserved to facilitate arthrodesis, and the risk is minimized for dural or nerve root injury.13 Given these characteristics and the favorable results reported by Harms,14 the TLIF approach has recently become far more prevalent. The high pseudarthrosis rates associated with early ALIF procedures have been alleviated by the advent of anterior plating15 and bone morphogenetic protein.16 In comparison to the TLIF or PLIF techniques, a more complete diskectomy can be achieved anteriorly, hence allowing placement of a larger graft. The anterior longitudinal ligament is resected along with the disk, end plate decortication is then performed, and an interbody implant [e.g., a poly (ether ether ketone) cage spacer17] is used to restore disk height and lordosis, thus decompressing the foramina indirectly.18 The incidence of retrograde ejaculation in males undergoing an ALIF may be as high as 5%19; this rate, however, is higher during interbody fusions performed at the L5–S1 level than at the L3–L4 interface, given the relative proximity to the superior hypogastric plexus. Furthermore, an even higher incidence of retrograde ejaculation has been reported following a transperitoneal approach to L5–S1 than a retroperitoneal approach.20 Anterior dissection involves retraction of the iliac artery and vein, with any injury leading to significant loss of blood.21 Anterior revision of an ALIF is associated with vascular complication rates of over 50% due to postoperative scarring.22 Finally, a multilevel ALIF usually necessitates concomitant posterior instrumentation to provide immediate stability.23 Given the lack of clear operative guidelines, we performed a systematic review of the literature to identify and consolidate the results of level I studies on the fusion strategies employed during operative treatment of symptomatic disk degeneration. The nonrandomized studies available in this field would certainly predict that no differences in functional outcome will be elucidated in comparing fusion techniques.24 Madan and colleagues,25 as an example, conducted a prospective but nonrandomized study that directly compared circumferential and posterolateral arthrodesis for patients with chronic low back pain in the setting of lumbar disk degeneration, finding no significant differences with respect to the ODI or return to work at a mean follow-up of 2 years. The Ovid MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, PubMed, HealthSTAR, CINAHL, and MDConsult databases were queried to find randomized, controlled trials, meta-analyses, and systematic literature reviews. Proceedings from the annual meetings of various spine societies and reference lists from review articles were assessed by citation tracking for potential inclusion. Each selected study was methodologically evaluated using criteria developed by the Cochrane Back Review Group. A qualitative synthesis of results was performed through methods adapted from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The four randomized, controlled trials identified by our comprehensive literature review are summarized in reverse chronological sequence herein. This prospective randomized study, which was awarded the 2006 ISSLS Prize, compared arthrodesis rates and functional outcome following instrumented circumferential fusion (consisting of a cage-based ALIF with concomitant pedicle screw fixation) versus instrumented posterolateral fusion. Initial analysis of these two study groups27 revealed that the circumferential group was characterized by longer operative time and improved restoration of sagittal lordosis. No differences were observed in operative blood loss or length of hospital stay. Moreover, both cohorts demonstrated significant improvement in the leg and back pain indices, as well as all four categories of life quality on the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. Patients undergoing the circumferential procedure, however, reported less leg pain at the 1-year follow-up evaluation and less peak back pain at 2 years. They fared better with respect to the reoperation rate for implant removal (7%), as compared with the posterolateral group (22%). The 360-degree fusion group also achieved a significantly higher posterolateral arthrodesis rate (92%) than the posterolateral group (80%), while maintaining their superior functional outcome [based on the ODI and Short Form-36 (SF-36) validated questionnaires] at 5 to 9 years postoperatively. This study entails the cost-utility assessment of the aforementioned randomized, controlled trial presented by Videbaek and colleagues.2 At 4 to 8 years postoperatively, the same investigators determined the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) for both circumferential and posterolateral fusions performed to treat severe, refractory low back pain. Circumferential fusion resulted in an incremental saving per QALY of $49,306, an accelerated rate of return to work, and higher net gains in health-related quality of life. A related level I study29 further found that circumferential fusions performed with femoral ring allografts (FRAs) resulted in a greater gain in QALY than those done using titanium cages (TCs). Another randomized, controlled trial30 had already shown that patients undergoing 360-degree fusion with FRA achieved greater postoperative improvements on the ODI and SF-36 than those who underwent the same fusion technique using TC. The Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group performed a landmark multicenter prospective investigation of three surgical strategies for lumbar fusion: (1) noninstrumented postero-lateral fusion, (2) posterolateral fusion with segmental transpedicular instrumentation, and (3) circumferential fusion consisting of instrumented posterolateral fusion in conjunction with interbody fusion performed via an anterior or posterior approach. Patients were randomized to one of these treatment arms in the setting of chronic low back pain that had remained refractory to conservative management. Regardless of the specific operative technique employed, the postoperative status of all cohorts at 2-year follow-up was characterized by reduced ODI, diminished pain on a visual analogue scale, and fewer depressive symptoms. Hence, no differences emerged in the subjective outcome measures for any of the fusion techniques; however, operative time, postoperative blood transfusions, length of hospitalization, and complication profiles correlated with the more demanding arthrodesis strategies. The fusion rate by plain radiographs also correlated with increasingly involved fusions, rising from 72% in the noninstrumented posterolateral fusion patients to 91% among those who underwent a circumferential procedure. This prospective, randomized trial compared functional outcome and perioperative parameters for a 360-degree fusion (ALIF plus instrumented posterolateral fusion) and a 270-degree fusion (ALIF plus transpedicular instrumentation alone). At a mean follow-up of nearly 3 years, ODI and pain had improved among both groups with no significant differential. Operative time, estimated blood loss, and length of stay were significantly lower for patients undergoing the 270-degree fusion. Operative management of lumbar spondylosis remains controversial due to the paucity of prospective, randomized studies. Based on the best evidence currently available, circumferential lumbar spinal arthrodesis represents the most reliable strategy in achieving fusion. Three of the four prospective studies identified also demonstrate improved long-term functional outcome through the circumferential method when compared with other techniques. Although reoperation rates are lower among the circumferential cohorts, trends toward increased complications in the early postoperative period are observed as well. Patients undergoing a circumferential fusion also revealed a trend toward increased operative time, intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative length of stay. In the most recent prospective, randomized research endeavor, Videbaek and colleagues26 found that both fusion rate and functional outcome correlate favorably with undergoing a 360-degree arthrodesis. Unfortunately, none of the randomized, controlled trials compare the various surgical options (e.g., APF versus ALIF) available for performing a circumferential fusion. For instance, no level I evidence exists for comparing an APF to a TLIF. A recent retrospective study by Faundez and coworkers33 demonstrated concordant functional outcome between APF and TLIF based upon the SF-36 and ODI, but more frequent intraoperative complications associated with the retroperitoneal approach for the APF cohort. Villavicencio et al34 similarly found that APF is associated with a more than twofold greater incidence of complications, increased blood loss, and longer operative and hospitalization times than TLIF. The small number of randomized, controlled trials performed to date suggest that circumferential techniques achieve greater rates of radiographic fusion, usually result in a superior functional outcome as compared with the posterolateral approach alone, and are associated with more postoperative complications in the short term. Due to the lack of concordance among these prospective trials, clear evidence-based guidelines cannot be formulated. Completion of additional level I studies is required before comprehensive evidence-based recommendations can be advanced for selecting the best strategy in the surgical treatment of symptomatic lumbar disk degeneration. Tables 19.1, 19.2 Pearls • Operative management of lumbar spondylosis with axial low back pain remains controversial due to the paucity of support from prospective, randomized studies. • Based on the best evidence currently available, circumferential lumbar spinal arthrodesis represents the most reliable strategy in achieving fusion and improved long-term functional outcomes. • Patients undergoing a circumferential fusion, however, trended toward increased operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative length of stay, and overall complications.

Surgery for Axial Back Pain: ALIF versus PLIF or TLIF

Methods

Methods

Level I Studies

Level I Studies

Videbaek et al26

Soegaard et al28

Fritzell et al31

Schofferman et al32

Discussion

Discussion

Conclusion

Conclusion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree