Surgical Technique

Shunt surgery is considered to be an easy surgery. Among neurosurgical operations, shunt placement is one of the least time-consuming procedures, and, with regard to surgical risk and microsurgical capability, it is also one of the least challenging. However, as most neurosurgeons are aware, shunt surgery has significant potential for complications. There are many details that may not be conducted in a perfect way and, therefore, may contribute to a poor outcome or even to complications.

There is no particular or a single specific method of performing shunt operation. Different surgical techniques may lead to successful outcomes. The here presented surgical technique for placement of a ventricular-peritoneal shunt (VP shunt) is based on personal experience and communication with other neurosurgeons. It is also based on the training experience and the practice in different neurosurgical centers.

11.1 Settings in the Operating Room

We follow the “shunt rules” established by Maurice Choux, especially those implemented for pediatric cases.1 Therefore, if it is an elective procedure, shunt surgery should be the first case in the morning. During surgery, the number of personnel in the operating room (OR) should be limited as much as possible (e.g., surgeon, assistant, anesthesiologist, scrub nurse). Shunt hardware must be in the OR before incision of the skin. Doors should be closed and marked with a sign that indicates shunt surgery is taking place and there will be limited access. There is no movement of staff in and out of the OR during surgery unless there is an emergency. As a standard procedure—as in many centers- a single shot of antibiotic prophylaxis (cefuroxime 1.5 g intravenously) is administered 30 minutes before incision of the skin. There is no routine use of antibiotics postoperatively.

Successful shunt surgery begins with the indication. The second most important step is to choose the appropriate shunt hardware. Ambulatory patients (i.e., the majority of patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus [iNPH]) are fitted with a gravity-assisted valve, while nonambulatory patients (i.e., the majority of patients with secondary NPH) are fitted with a differential pressure valve. Ambulatory patients have an increased risk of overdrainage. Patients who are nonambulatory, but remain in a horizontal position for most of the day, have a lesser risk of overdrainage and may benefit from a differential pressure valve.

The initial pressure of the valve is set to 5 cm opening pressure; this can be adjusted in adjustable valves before surgery. Further details about shunt and valve settings can be found in Chapter 15, and a discussion about overdrainage and underdrainage and their related complications can be found in Chapter 10.

11.2 Positioning

Positioning of the patient is essential for smooth-running of surgery and should be performed by the surgeon or an experienced assistant. If there is no reason to operate on the patient’s left side (like previous surgeries or implants), then we prefer to operate on the right side. The patient should be in a supine position. The head rests either in a horseshoe-head holder or on the table in a gel head ring. The head is turned to the opposite side, usually rotated 45° to 60°, and slightly tilted posteriorly. The right shoulder is slightly elevated. There should be a straight line between the chest, neck, and retroauricular region to allow for easy tunneling.

11.3 Shaving and Disinfection

In adult patients, we shave the frontal, temporal, and retroauricular regions with clippers. In contrast, in children (not a topic of this book), we shave only a small strip following the shunt path or, in newborns, we do not shave the head at all. In our opinion, it is important to manually clean the skin before disinfection. The surgeon should then perform the disinfection so that he or she can recognize the required borders of the surgical field. This is especially important in revision cases or if there is a potential change in the surgical plan during the procedure; the surgeon may need to think in advance about the extent of disinfection.

11.4 Draping

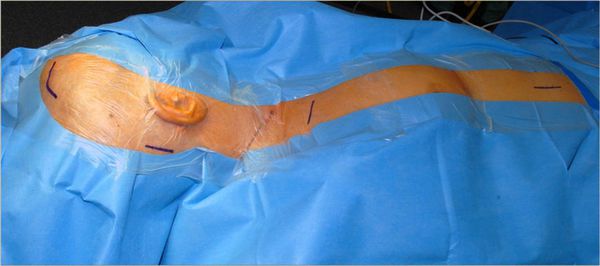

The surgeon should also perform the draping. We start with a surgical foil that covers nearly all of the disinfected skin. The foil should be applied when the patient’s skin has completely dried. Overlap is possible. The draping is then applied from head to abdomen, starting with a U-shaped drape on the head, followed by two straight drapes on each side, finishing with a large straight drape perpendicular to the latter drapes. Of course, application of the drapes first and the foil second is also possible. Once the draping is finished, the rest of the instruments required for surgery are brought on to the table. Afterward, gloves are changed (▶ Fig. 11.1).

Fig. 11.1 Patient positioned and draped for a right ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

11.5 Surgical Procedure

Two surgeons perform the surgery together. The hardware is placed in a proximal-to-distal direction. We begin with a precoronal bore hole, implant the ventricular catheter, followed by the valve, and then the distal peritoneal catheter. Other surgeons prefer to operate from both sides, one surgeon starting at the bore hole, the other at the abdominal incision.

The shunt should be handled with instruments rather than the surgeon’s hands or gloves (if possible) so as to avoid any contact with the patient’s skin, and the shunt should be taken out of the package as late as possible before implantation. If, for any reason, the shunt is kept outside the package, then it should be covered with sterile fluid.

11.5.1 Ventricular Catheter

The skin incision for the frontal approach is curved linearly. This type of incision allows for the placement of a bore hole reservoir completely under the skin and avoids having to puncture the reservoir later through an incision in the skin.

The bore hole is placed at Kocher’s point, which is 2 cm precoronal and 3 cm paramedian. Use of the standard measurements of 11–3–6 is highly recommended: the bore hole should be placed 11 cm above the nasion (which, in Caucasian patients, is 2 cm anterior to the coronal suture); 3 cm paramedial to the midline; and the proximal catheter should be advanced into the brain 6 cm from the inner table of the skull. Anatomical landmarks (to puncture the ipsilateral frontal horn) are the median cantus of the ipsilateral eye and the tragus of the ipsilateral ear. Following these measurements, it is possible to place the ventricular catheter in the frontal horn, away from the foramen of Monro in nearly all patients, even if they have small ventricles. Different methods for optimal positioning of the ventricular catheter have been published.2

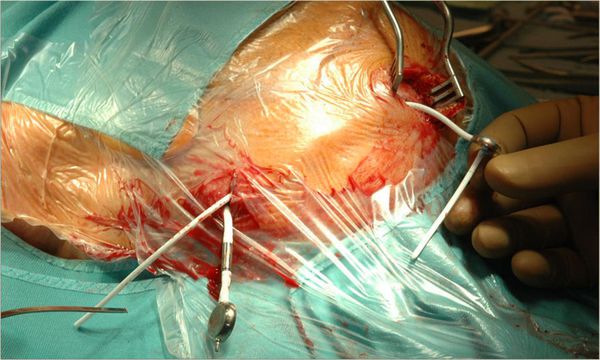

After placement of the bore hole, first the dura is opened and then the arachnoid. Ventricular puncture should not be performed without incising the arachnoid. We connect the ventricular catheter, which has a length of 6.5 cm (bringing it exactly 6 cm into the brain measured from the inner table of the skull), to a bore hole reservoir before its placement in the ventricular system. From the bore hole reservoir, a distal catheter, leading to the valve, is placed in a subgaleal plane and it appears at the second skin incision behind the ear (▶ Fig. 11.2).

Fig. 11.2 Patient operated on the left side. The ventricular (proximal) catheter is connected to the bore hole reservoir and the distal catheter (coming from the reservoir) is positioned in the subgaleal plane. The valve and the peritoneal catheter have already been positioned subcutaneously.

After this part of the shunt has been placed under the skin, the ventricular system is punctured usually using a Cushing or Scott cannula. After the puncture and confirmation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow, the entire cannula is removed and—using bayoneted anatomic forceps—the proximal catheter is advanced using the same puncture tract into the ventricular system. Once the catheter has reached the ventricle, CSF will flow into the bore hole reservoir.

After mild pumping, distal CSF flow will occur. At this point, CSF is taken for laboratory tests (e.g., glucose, sugar, protein, cell count) and, if indicated, samples for gram stain and culture are also taken. We avoid taking CSF from the ventricular catheter directly after the puncture because, in small ventricles (which are rare in patients with NPH), the surgeon may lose the opportunity for a second puncture, if needed, when the ventricle becomes too small (▶ Fig. 11.3, ▶ Fig. 11.4, ▶ Fig. 11.5).

Fig. 11.3 Puncture of the ventricle utilizing a Scott cannula.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree