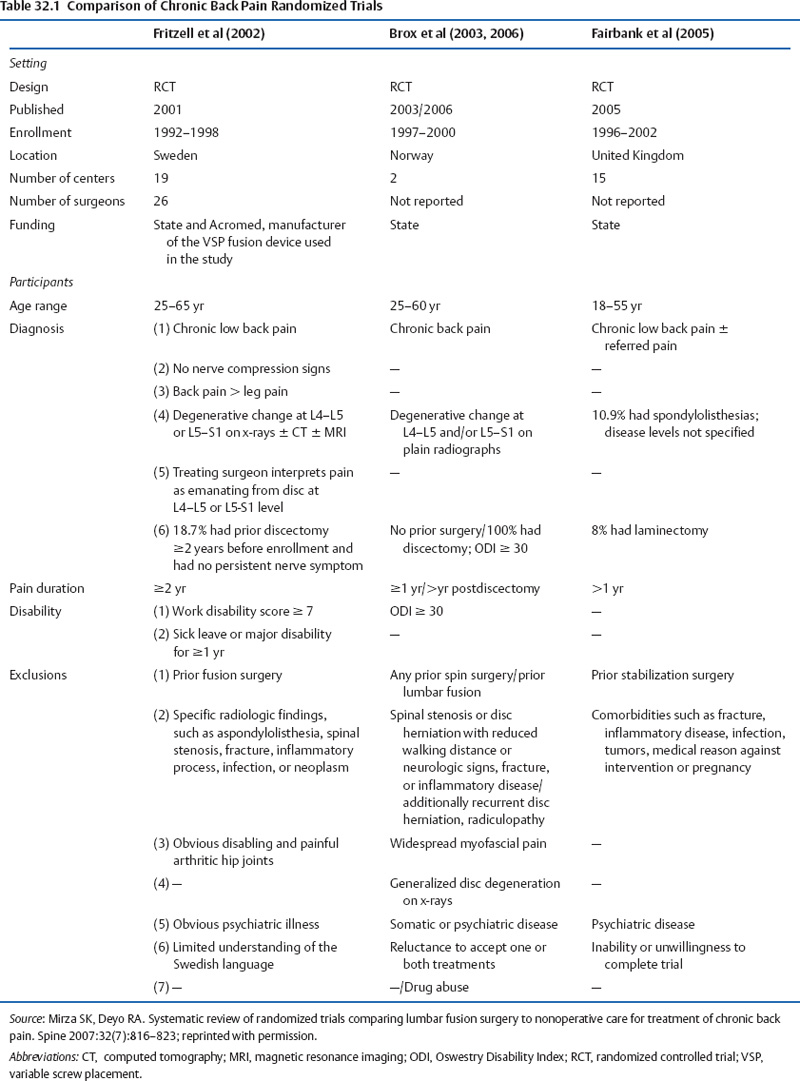

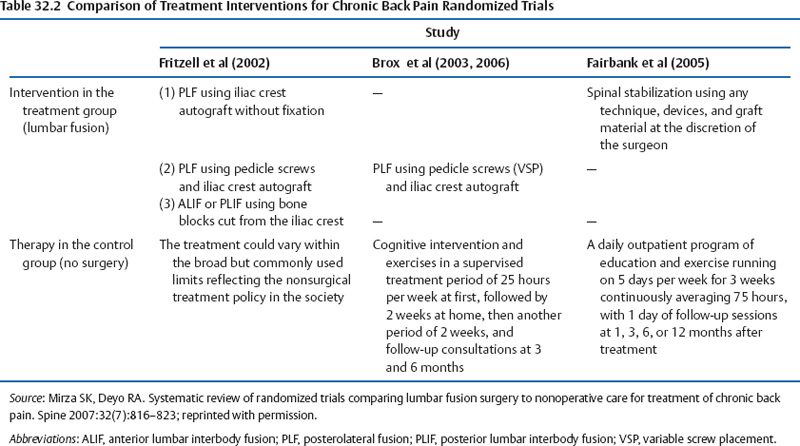

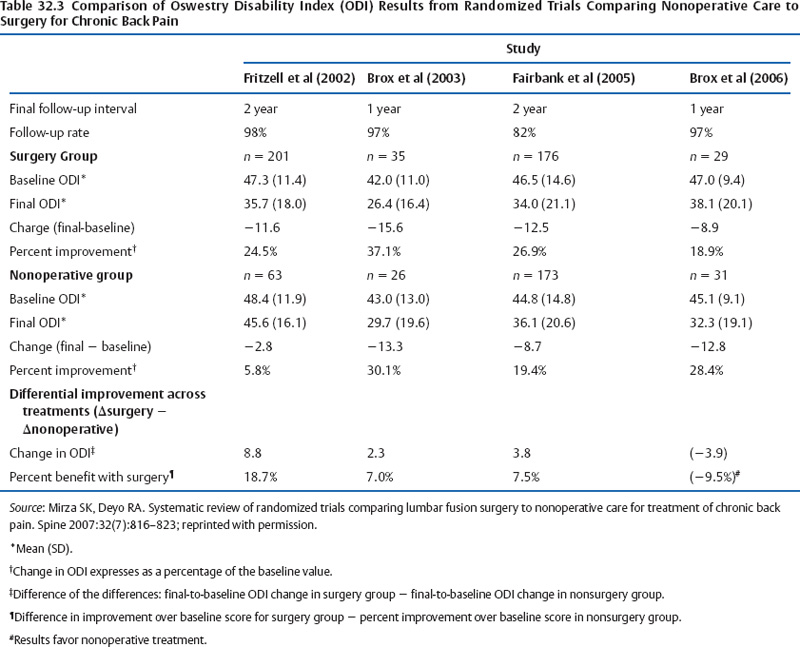

32 Surgical Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Disc Disease: A Critical Review Stewart M. Kerr, Andrew P. White, and Todd J. Albert Surgery rates for degenerative lumbar conditions vary regionally within the United States.1 There also is a dramatic difference seen when comparing U.S. trends to other developed nations.2 The volume of spinal surgery has also been increasing over time; investigators have reported a 200% increase in the number of lumbar spinal fusions performed in the United States annually since the late 1980s.3,4 This epidemiologic information, considered alongside lay press editorials and conflicting medical opinions, has raised questions regarding the appropriateness of surgery for degenerative lumbar conditions. Although it is widely accepted that some degenerative lumbar pathology such as neurocompressive conditions that result in progressive lower extremity motor deficit or cauda equina syndrome should be managed operatively, surgical indications for many other degenerative lumbar processes are not as clear. Most humans will experience back pain at some point in their life and most often an identifiable cause cannot be determined. The contemporary literature is replete with reports describing operative treatments for various lumbar degenerative conditions. Collectively determining which patients will likely benefit from spinal surgical procedures is not well described, and unfortunately many current reports lack sufficient power or have inherent methodologic flaws hindering management consensus. Indeed, even high-quality level 1 studies often show fairly equivocal results when evaluated with “intent-to-treat” principles. These results are understandably perplexing to clinicians, patients, policymakers, and the health insurance industry. The extent of surgical intervention, if any, for many of the degenerative processes in the lumbar spine remains controversial from an evidence-based medicine standpoint. Society is relying on the sound judgment of health care professionals to “do the right thing” with limited fiscal resources. The need for evidence to guide our surgical actions will likely grow in importance as budgets experience the costly reality of an aging population. In the absence of tumor or infection, the etiology of lumbar pain is poorly understood. Even in relatively straightforward clinical scenarios such as nerve root compression caused by a herniated nucleus pulposus, it is clearly possible for a wide variety of symptoms or even no correlation with the extent of abnormality seen on radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).5–10 Resolution of the painful motion segment often requires (1) decompression of symptomatic neural elements that are persistently refractory to nonoperative management, (2) fusion of unstable motion segments while restoring anatomic lordosis, and (3) pain generator ablation. If possible, this would be performed without disruption of nonpathologic physiologic structures such as the paraspinal musculature. Determining the pain generators for less obvious findings or selecting which region or segment is problematic within the lumbar spine is not always possible. Of those patients with back pain, only a small proportion go on to have chronic symptoms. A much smaller percentage will eventually undergo surgery. Locating pain etiology begins with careful clinical evaluation and, in addition to various imaging studies such as MRI (Fig. 32.1), may include invasive procedures such as provocative discography (Fig. 32.2), epidural steroid injections, facet injections, and selective nerve root blocks. Psychological evaluation is also warranted to identify depression, hysteria, and other diagnoses that would adversely affect a potential surgical intervention. Fig. 32.1 Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan of a 36-year-old man with severe low back pain that has not responded to a full course of nonoperative management. The L5-S1 disc is desiccated with a central bulge. Fig. 32.2 (A) Lateral and (B) coronal computed tomographic discograms. Pain was strongly concordant at L5-S1; signs of disc and endplate degeneration are seen. The discs at L3-L4 and L4-L5 are normal appearing and were not painful with provocative discography. Mirza and Deyo11 recently published a systematic review comparing randomized surgical trials to nonoperative care for chronic lumbar pain. Of 35 citations, only four trials met the criteria; all were conducted in Europe.12–15 The principal features from these commendable investigations are highlighted in Tables 32.1, 32.2, and 32.3. In Fritzell and colleagues’ work (the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study), patient outcomes were compared from 310 nonoperative and surgical patients with disabling lumbar pain.14 The surgical management was one of three fusions; nonsurgical treatment was highly structured and included physical therapy, informative sessions, cognitive training along with other interventions such as injections or acupuncture therapy. The fusion patients, when compared with the nonoperative cohort, enjoyed improved resolution of back and leg pain (32% as compared with 6.8%). They also experienced higher satisfaction (62.6% versus 29% patients reporting “much better” and “better”) and had increased RTW rates (39% versus 23%). One significant limitation of this study was the high degree of crossover between assigned patient groups; many patients ultimately received treatment that they were not originally randomized to receive which limited the power of the intention to treat analysis. Therefore, “as treated” analysis was used, which devalued the report. The Swedish Lumbar Spine Study also reported the results of three spinal fusion techniques for treatment of degenerative, disabling low back pain.16 Patients were randomized to groups for posterolateral fusion (PLF) without internal fixation, PLF with variable screw placement (VSP), and interbody fusion (anterior or posterior, per surgeon preference). Fusion rates were 91%, 87%, and 72% for interbody, PLF with VSP, and PLF without screw fixation, respectively. Even with this difference in fusion rates, however, patient outcomes did not significantly differ; all groups experienced decreased pain and disability at 2 years of postoperative follow-up. Brox and colleagues attempted to repeat the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study in 2003 and 2006. They compared PLF with VSP to nonoperative treatment in an effort to address the shortfalls related to high crossover rates and a heterogeneous nonoperative cohort. Cognitive rehabilitation and therapy that stressed core strengthening were emphasized. The primary outcome measure (Oswestry Disability Index; ODI) showed no significant difference between the treatment cohorts. Understandably, the nonsurgical experienced significantly higher fear-avoidance scores compared with those surgically managed. The power of each of these studies has been criticized due to the number of participants was small (61 in 2003 and 57 in 2006).12,13 In 2005, Fairbank and colleagues published a related randomized prospective study of 349 patients comparing fusion to nonsurgical treatment. The nonoperative group followed an intensive rehabilitation program that emphasized endurance, stretching, and stabilization exercises along with cognitive therapy. Improvement in the ODI was only marginal; it was concluded that even though such an intense rehab program was unlikely to be available to the average patient, it was effective at reducing both low back pain and the inherent complications that arose in almost 11% of the surgical cohort.15 In summary, all four studies report modest advantages of surgery compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar pain secondary to spondylosis. Mirza and Deyo suggest that the large differences seen in nonsurgical improvement may be important for further investigation.11 The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) reports the results of two large studies representing level 1 evidence on the treatment of common spinal disorders. Eleven centers across the United States were used to compare clinical outcomes for surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for several diagnoses at various follow-up times. The study examining lumbar disc herniation enrolled 743 patients. All had symptoms and confirmatory signs of lumbar radiculopathy with a corresponding disc herniation validated by imaging. Five-hundred twenty-eight of these received surgical treatment of a standard open discectomy with decompression of the nerve root if needed; 191 received nonsurgical treatment (i.e., therapy, education, home exercises, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs). At 3 months of follow-up as defined by the SF-36 Pain Survey, the surgical group experienced significantly better bodily pain measures compared with the nonsurgical group (40.9 versus 26.0). The ODI scores also favored the operative group at 3 months (mean change, -36.1 versus -20.9). This significant margin reduced at 2 years; the nonsurgical group showed steady pain reduction to a score of 32.4. Bodily pain reported by the surgical group showed only moderate continued improvement to 42.6. Likewise, the ODI scores also followed this trend at 2 years with the nonoperative group (-24.2) gaining more ground than the surgical group (-37.6).17,18 The authors concluded that although both treatments helped to resolve back pain and sciatica at 2 years of follow-up, those who received surgery experienced more immediate pain relief and greater initial improvement.

Decision Making about Treatment

Review of Medical Evidence for Surgical Treatments of Degenerative Lumbar Disc Disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree