(1)

Neurosurgical Department, Friederiken-Hospital, Hannover, Germany

7.1 Technical Implications

The surgical treatment of focal entrapments predominantly consists of nerve relief and decompression. Entrapment syndromes are lesions in anatomically narrowed regions. First, normally existent anatomical structures can start to irritate the nerve. Second, the site where the nerve pierces a hard fascia can constrict the tissue. Third, the roof of a preformed tunnel can compress the nerve when additional structures within the tunnel develop chronic swelling. Subsequent surgery aims at removing the irritating structure, widening the piercing site, or transecting the ligamentous roof of the preformed tunnel. This kind of surgery remains restricted to the paraneural space. The epineurium and all of its contents remain untouched. Intraneural tissue reactions like fibrosis have to be avoided if at all possible.

In the 1970s, interfascicular neurolysis procedures were favored even in carpal tunnel symptom cases [1]. Thereafter it became quiet again concerning these tendencies; we must suppose that the considerations of Sect. 4.2 gave reason to its re-disappearance.

Nevertheless a confrontation with an entrapment case which presents a preoperative severe loss of function as well as an unexpected impairment of electrical nerve conductivity is not rare and happens repeatedly. Occasionally during operation the surgeon can then find an unusual thickening and hardening of a nerve segment and has to decide immediately whether to leave the nerve behind with bad prognosis or to start a microneurolysis [2]. During the last few decades, scientific discussions have taken place on the option of stepwise neurolysis in these special cases of fibrosis resp. pseudoneuroma. The fact that such a procedure can increase pain, and even induce a neuropathic pain as previously demonstrated in Sect. 4.2 must not be neglected. Alternatively, when we leave fibrosis behind, chronically manifested motor deficits will probably not improve. Progressed ulnar nerve and tibial nerve neuropathies may intra-operatively present these unpleasant dilemmas.

Compared to entrapments, an iatrogenic focal nerve injury frequently affects for instance the spinal accessory nerve [3]. Further iatrogenic injuries to other nerves can follow screw removal procedures. Function deterioration can occur after bone injury followed by scars in the surroundings, as well as by scars after arterial puncture and hematoma. Sometimes, such injury related focal neuropathies then need more than a simple outside decompression, especially, if the thin spinal accessory nerve is involved as described in Chap. 8.1. If pain is not in the foreground and improvement of motor deficits is particularly required, neurolysis steps have absolutely to be taken into account. The surgeon has to decide immediately because subsequent approaches carry greater risks of worsening. The natural explanation is that the primary surgeon already leaves scar tissue behind. Thus, the primary surgeon bears the entire responsibility.

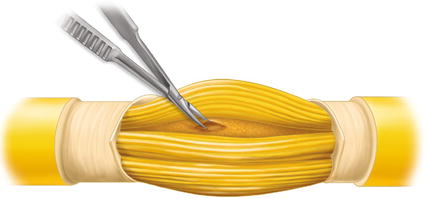

We therefore do not hesitate to describe the procedure of neurolysis, and in doing so, point out that it is a stepwise procedure [4]. It should be stopped immediately if the microscope shows that fascicles are swelling. The following different neurolysis steps must not be engaged at any price in order to prevent any following neuroma pain. Under magnification, the epineurium in the intact part of the nerve proximal and distal to the involved area can be incised longitudinally. After that, the external sheath of the epineurium which surrounds the nerve trunk can be removed. As the third step, separating of fascicle groups from each other can start – “interfascicular neurolysis”. Our goal has to be to achieve sufficient decompression to enable the axon sprouts to overcome the lesion and reach their target. We must always bear in mind that a fibrosis of connective nerve tissue exerts circular compressing forces on the fibers. As result, a grade II lesion according to Sunderland’s classification occurs (see Sect. 3.1). The re-growing capacity of nerve axons starts when these forces are decreased. This factor forms the basis of “neurolysis.” We expect increased criticism with regard to these considerations. However, when patients with progressed motor deficits and even without any injury in their history, and without pronounced pain, demand improvement, the surgeon has either to advise and apply or to deny such neurolysis steps. Gender neutral: The surgeon has the responsibility and has to make the final decision; it may be influenced by preoperative discussions with the patient about risks concerning pain. These reservations do not apply to surgeons dealing exclusively with efferent nerves like the spinal accessory, anterior, or posterior interosseous nerves. They are without any pain risk of course (Fig. 7.1).