Surgical Treatment of High-Grade Spondylolisthesis: An Analysis of 18 Patients

Maryline Mousny

André Kaelin

Spondylolisthesis was first described in 1782 by Herbiniaux, a Belgian obstetrician (1). Taillard precisely defined this condition only in 1957 (2). Nowadays spondylolisthesis is a well-known condition and remains the commonest identifiable cause of low back pain in children and adolescents (3). The exact incidence of dysplastic spondylolisthesis is unknown, but this type makes up 14% to 24% of treated cases in large series, with a 2:1 female:male ratio (4). Today, most of the authors agree on the treatment of mild to moderate spondylolisthesis, but controversy still exists over the most appropriate method for managing high-grade spondylolisthesis (5). A lot of treatment options are proposed in the current literature (6,7,8,9,10).

In our institution, we perform a posterior interbody and posterolateral fusion with segmental pedicle fixation when the slip is greater than 50% with a lumbosacral kyphosis. No forceful intraoperative reduction maneuver is performed, but a partial reduction is usually obtained by positioning the patient. In cases of spondylolisthesis with radiographic progression or greater than 50% slip but without lumbosacral kyphosis, we perform an in situ posterolateral instrumented fusion. The purpose of the present report is to evaluate retrospectively the radiographic and functional outcome of patients operated on for moderate to high-grade dysplastic spondylolisthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eighteen patients who were operated on for moderate to severe dysplastic-type spondylolisthesis from 1988 to 2000 at Hôpital des Enfants in Geneva were reviewed retrospectively. Clinical records and serial radiographs were evaluated.

The surgical indications included severe L5-S1 spondylolisthesis (Meyerding (11) Grades 3 or 4), radiographic progression (six patients), and severe pain. All patients complained of unremitting pain. All the cases presented radiographic features of severe dysplasia and were therefore classified as dysplastic-type spondylolisthesis according to the Wiltse classification (12,13).

We recorded the relevant points in the personal and familial previous history of each patient. The practice of any sports activity was noted. Pre- and postoperative clinical measurements included activity level, symptoms, posture (presence or absence of a lumbosacral kyphotic deformity and lumbar hyperlordosis, a lumbar step-off, an associated scoliosis), lumbar forward flexion, neurologic findings, straight leg raising, and gait pattern.

FIG. 16.1. High-grade spondylolisthesis, with slipping of L5, L5-S1 kyphosis, and dysplastic change of vertebrae. |

Mean clinical and radiologic follow-up was 6.5 years (range 3 to 14.5 years). At latest follow-up, all patients but two had reached skeletal maturity.

Patients

The 18 patients who underwent operative stabilization had symptomatic dysplastic-type spondylolisthesis (Fig. 16.1). Nine were female, and nine were male. The average age at the initial symptom was 14 years (range 11 to 17 years). The average age at diagnosis was 15.2 years (range 6 to 18 years). The average age at diagnosis is less than the average age at initial symptom because the diagnosis was fortuitously made in two patients and they became symptomatic later. Regarding the other patients, the average interval from first complaints to time of diagnosis was 11 months (range 0 to 36 months).

All patients had conservative treatment prior to surgery: physiotherapy and medication for 15 patients, physiotherapy and bracing for 8 patients. All patients were improved with the bracing, but the pain reappeared when they tried to wean.

The average age at surgery was 16 years (range 11.7 years 10 months to 20.1 years). The interval from time of diagnosis to time of operation averaged 11 months (range 1 to 60 months). Nine patients hadn’t reached skeletal maturity at surgery. All the patients but one had no history of trauma. Four patients participated in repetitive lower risk sports, and one patient in high-risk sports (gymnastics). Three patients had a familial history of spondylolisthesis (direct relatives). Regarding the associated conditions, one patient suffered from anorexia nervosa, one patient had been treated for hip dysplasia, one patient for bilateral Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, and one patient for clubfoot.

Back pain was the most common complaint at the first visit. All patients described lumbar pain. Eight patients had concomitant radicular pain about one or their two lower extremities. One of these patients had typical cruralgia, while the other patients complained of sciatic-type pain. Seven patients were concerned by their postural deformity and abnormal gait. All patients complained of tight hamstrings, and 12 had a significant step-off deformity in the lumbosacral area. All patients had lumbosacral kyphosis. Four patients had scoliotic deformity.

Eight patients had a neurologic finding on preoperative evaluation. Two patients had a one-grade decrease on motor testing of L5 innervated muscles (one in both legs and two in the left leg). Three patients had positive Lasegue test without motor deficit at clinical examination. One patient had mild sensory disturbance (dysesthesia) in L5-S1 distribution and decreased ankle jerk test in the right leg. One patient had decreased quadriceps jerk test on the right side. Four patients had an abnormal, waddling-type gait.

Radiographic Evaluation

Standing lateral and anteroposterior radiographs were measured at the following intervals: at diagnosis, preoperatively; at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively; and at last follow-up. These radiographs were taken with the patient standing because the slip angle can change more than 11 degrees between standing and supine radiographs (14). Hyperextension and hyperflexion radiographs were taken preoperatively.

Radiographic measurements included: (a) percentage of slip (i.e., anterior displacement of L5 /or L4 on S1 /or L5) (2) and (b) slip angle of L5 on the sacrum, using the inferior endplate of L5 and the perpendicular to the posterior body of S1 (14). We used the percentage of slip and the displacement index to determine preoperatively the presence or absence of instability on the dynamic radiographs. We also measured the lordosis angle L1-L5. The radiologic criteria for fusion was the presence of a fusion mass on plain radiographs, posteriorly when only a posterolateral fusion was performed, or posteriorly and between the two vertebral bodies when a posterolateral and interbody fusion were performed.

The disc spaces were preoperatively assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. If the L4-L5 disc was intact, a single-level L5-S1 fusion was performed; if it showed signs of degeneration, a L4-S1 fusion was performed.

Surgical Technique

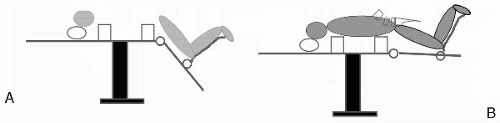

The patient was placed prone, on a four-poster soft frame, with the hips and the knees in a 90-degree flexed position (genupectoral position). Nerves roots monitoring for sensitory and motor pathways were installed. A longitudinal midline posterior incision was made and subperiosteal dissection from the spinous process of L3 to S2 was performed. The L5 lamina was removed. The nerve roots (L5, S1) were decompressed and the cauda equina was freed gently from the posterosuperior zone of the first sacral vertebral body. Transpedicular screws (CD Instrumentation or CD Horizon) were inserted at L5 (or L4) and S1 level under the control of image intensifier, for the last cases under CAOS (Medivision). A lateral roentgenogram was obtained to confirm the proper position of the screws. The screws were intentionally inserted in a lateral and convergent fashion. The goal was to obtain a “triangulation effect” and therefore good stability. A slight distraction was performed to open L5-S1 disk space. The L5-S1 intervertebral disk was removed and a 0.5-cm sacral dome osteotomy was performed. Corticocancellous graft was placed in the interbody space. A cage (posterior lumbar interbody fusion, or PLIF) was also used when the foraminal space was not enough open. Then the position of the patient was changed, and the hips were extended to permit the movement of the pelvis under L5. During this maneuver, a direct visualization of the nerve roots was possible, allowing detection of any nerve impingement.

Changing the position of the patient allowed partial correction of the lumbosacral kyphosis (Fig. 16.2). The rods (CDI) were first inserted proximally and then progressively

fixed to the sacrum. A satisfactory correction of the kyphosis was obtained when the L5 transpedicular screws were parallel to the S1 screws. Usually the discectomy allowed good mobilization of the L5 vertebra. The sacral dome osteotomy prevented any tension on the nerve roots. Segmental compression was applied between the two vertebrae. The compressive forces applied on the construct helped to maintain the achieved reduction (the restored lumbar lordosis). Local autogenous and allogenous bone graft was placed posteriorly and posterolaterally on all available surfaces after decortication. Postoperatively, under brace protection, ambulation was permitted as soon as possible. The patient was discharged at 6 to 8 days after surgery; the removable orthosis was worn 4 months. Activity was restricted until solid fusion occurred. Twelve patients had L5-S1 fusion, and 6 patients had L4-S1 fusion. All patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis (≥50°) had posterior interbody and posterolateral fusion.

fixed to the sacrum. A satisfactory correction of the kyphosis was obtained when the L5 transpedicular screws were parallel to the S1 screws. Usually the discectomy allowed good mobilization of the L5 vertebra. The sacral dome osteotomy prevented any tension on the nerve roots. Segmental compression was applied between the two vertebrae. The compressive forces applied on the construct helped to maintain the achieved reduction (the restored lumbar lordosis). Local autogenous and allogenous bone graft was placed posteriorly and posterolaterally on all available surfaces after decortication. Postoperatively, under brace protection, ambulation was permitted as soon as possible. The patient was discharged at 6 to 8 days after surgery; the removable orthosis was worn 4 months. Activity was restricted until solid fusion occurred. Twelve patients had L5-S1 fusion, and 6 patients had L4-S1 fusion. All patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis (≥50°) had posterior interbody and posterolateral fusion.

RESULTS

Clinical

All patients operated on described improvement of their back pain. At latest follow-up, 13 patients had complete resolution of their back and lower leg pain. One patient still described some discomfort at the lumbar spine; four had occasional pain during sports activities. Regarding their sports ability, all patients were at the activity level they desired and returned to their former activities. No patient had hamstring tightness postoperatively. The patients with scoliosis showed no progression of their curves at the latest follow-up. All patients had improvement in their cosmetic appearance as well as in their gait. Two patients still clinically demonstrated a lumbar hyperlordosis. Two patients had L5 mild paresis, one with full recovery at 2 weeks postsurgery, one with partial recovery (patient needed a second surgery).

Radiographic

As previously mentioned, all patients had dysplastic-type spondylolisthesis. Seventeen patients had an obviously rounded upper sacrum. Regarding associated vertebral malformations, six patients had spina bifida (one at L5, three at S1, one at L5-S1, and one at L4-L5-S1). A hypoplasia of the posterior arch of L5 and S1 was noted during the surgical procedure in one patient.

The mean percentage of slip was 73.1% (range 56.7% to 100%). The mean L5 slip angle was 38 degrees (range 21° to 51°). The mean sacral inclination was 44.3 degrees (range 13° to 62°). The lumbar lordosis measured an average of 58.1 degrees (range 40°

to 80°). Four patients had an associated scoliosis. Two patients had a thoracic curve, convex to the right, and two a lumbar curve.

to 80°). Four patients had an associated scoliosis. Two patients had a thoracic curve, convex to the right, and two a lumbar curve.

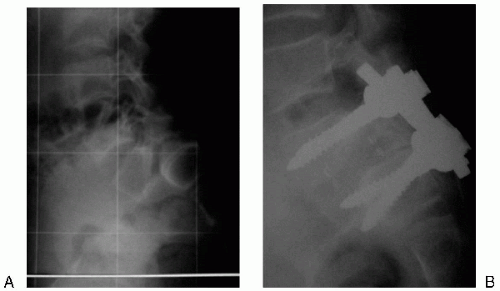

FIG. 16.3. X-ray pre- and postreduction done by posterior approach, sacral osteotomy, PLIF, and posterior instrumentation in compression. |

Postoperatively, the mean percentage of slip was 42% (range 5% to 70%). All patients showed an improvement of the slippage with a mean improvement of 31%. Using Meyerding classification, six patients improved by one grade, five patients by two grades, and four patients showed no improvement. At latest follow-up, the mean percentage of slippage was 44% (range 16% to 73%). Three patients nevertheless showed a small loss of reduction.

The mean postoperative L5 slip angle was 5 degrees (range −3° to 10°). At latest follow-up, the L5 slip angle worsened in one of the three patients, showing a postoperative progression. The final result was nevertheless an improvement of the slip angle, with a mean angle of 6 degrees (range 3° to 11°).

The mean postoperative lumbar lordosis averaged 45.1 degrees (range 18° to 66°). No statistically significant difference was noted at the last follow-up (Fig. 16.3).

The three patients with associated scoliosis showed no worsening of the curves. Regarding the hardware, one sacral pedicular screw was found broken in two patients, one patient after 6 months and one patient after 3 years, without consequence. Among the three patients with postoperative worsening, both sacral pedicular screws were found broken in one patient at 1 year.

The quality of the fusion at 6 months was difficult to assess in four patients. One of these patients (patient 1) has been followed up for 6 months, and two others presented a postoperative progression. All patients but one (patient 1, with a 6-month follow-up) had a radiographically mature fusion 1 year postoperatively.

Complications

Postoperatively, two patients had mild paresis of the anterior tibialis. The recovery was spontaneous and complete for one patient. One patient operated on for a high-grade spondylolisthesis (L5-S1 fusion) showed a recurrence of the slippage with appearance of neurologic signs in the lower extremities and had secondary surgery 1 week after the first procedure. No other complications were noted.

DISCUSSION

Although most authors agree on the treatment of low-grade spondylolisthesis, there is still a lot of controversy about the treatment of high-grade spondylolisthesis. Harris and Weinstein (5) have found that 57% of patients (21 patients, age ranging from 11 to 25 years) treated with in situ posterolateral fusion were asymptomatic compared with 36% of patients (11 patients, age ranging from 10 to 24 years) treated conservatively. The operative group were less symptomatic and more active than the nonoperative group. It seems thus that the outcome is better for the operated patients. But controversy remains over what procedure must be performed and a lot of surgical techniques have been described in the literature, including for example in situ posterolateral fusion (7,13,15,16,17,18,19,20,21), reduction and fusion through a posterior approach (10,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30), reduction and posterolateral fusion followed by anterior interbody fusion L5-S1 (31), reduction and anterior interbody fusion (32), reduction and combined fusion (3,33,34,35,36), L5 corporectomy (8,37). The main arguments against fusion in situ have been a higher rate of pseudarthrosis (5,14,18,20), a higher risk of postoperative slip progression (14), and the persistence of the cosmetic deformity (14,15,18). Among the surgeons performing reduction, it’s usually accepted that correction of the kyphosis is of primary importance, while correction of the anterior shift is of only secondary importance (14,26,29,38,39,40,41). The improvement of the lumbosacral kyphosis offers some advantages as compared with fusion in situ. It improves spine mechanics above the fusion, and it creates a spinal balance that is favorable for the achievement of a good fusion (42). It also improves the global sagittal contour and cosmetic appearance. But it’s noteworthy that very few patients complain about their cosmetic deformity (15,17,18,20). In their comparative study, Harris and Weinstein (5) noticed that no patients were dissatisfied with their cosmetic appearance. Whatever surgical option chosen, the goal must be to obtain stable fusion (39,40,43,44). It has been observed that once bony union or stability has been achieved, resolution of pain occurs, even in the presence of minor neural deficits, and hamstring spasm as well as the associated gait abnormalities resolve (14,15,45,46,47). Haraldsson et al. (48) compared spondylolisthesis in adolescents and children and showed that the most important cause of the preoperative symptoms observed in young people were instability at the level of the defect. Therefore, they suggested that the goal of treatment was to obtain stabilization. In our study, only four patients were concerned by their cosmetic appearance. Back pain was the most common complaint. At latest follow-up, 13 patients had complete resolution of their back pain, and two patients still complained of some lumbar discomfort but without consequence on their activity level. All patients but one had a radiographically mature fusion mass at latest follow-up. We have tried to assess as precisely as possible the radiographic results by taking different measurements, but it must be noted that the regional landmarks are often obscure, making inherent error in measurement possible. This problem of inaccuracy of landmarks during roentgenographic measurements has also been pointed out by other authors (5,29,49,50).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree