Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding

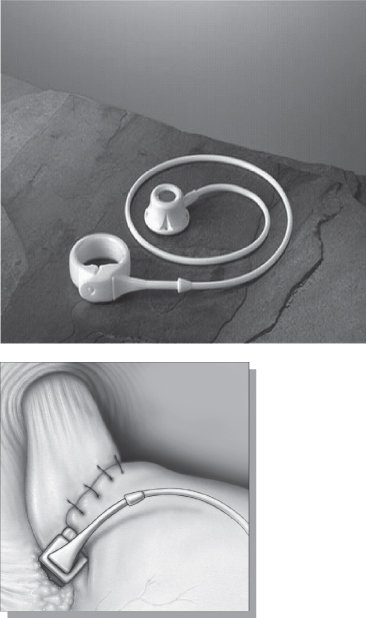

The most widely used restrictive procedure as of this writing is the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band placement (see Figure 19-1). In this procedure, a silastic band is placed around the upper part of the stomach, creating a small upper gastric pouch (typically holding 30 cc). The band itself forms a stoma between the upper pouch and the remainder of the stomach. The inner surface of the band consists of a balloon, which can be inflated with variable amounts of saline to alter the size of the stoma and thus adjust the rapidity of emptying between the pouch and the remainder of the stomach.

The band is attached to an injection port with a silastic tube; the port is implanted on the abdominal wall fascia. Adjustments of the stoma size can therefore be made at any time after surgery via the injection port. This device was first described by Kuzmak in 1990, and the Allergan/Inamed LAP-BAND® system was approved for use in the US by the FDA in mid-2001 (31). Ethicon recently introduced another adjustable gastric band, the REALIZE® Band, approved for use in the US by the FDA in late 2007.

The attraction of the adjustable gastric band to most patients and medical providers is its relative simplicity. In many instances, the procedure can be performed in an outpatient setting where the patient goes home the same day as surgery. Ultimately, once properly adjusted to a particular patient’s needs, the band will offer portion control. As there is no malabsorption involved, the success of this procedure is highly dependent on patient compliance. Patients must be counseled on proper food choices and eating habits to maximize success of the adjustable gastric band system.

Serious complications are rare, especially when compared to other weight loss procedures. The risk of gastroesophageal perforation and its potentially devastating consequences is low. Implant-related events are most common, including port infections, tubing breaks or disconnections, band erosion, or band slip, with a total implant-related complication rate of approximately 10%. Although uncommon and often occurring late after placement, erosion of the band through the stomach can occur, causing an ulceration, hemorrhage or perforation. A band slip occurs when the stomach prolapses up under the band, creating a larger pouch above the band. Rarely this can lead to gangrene or complete obstruction, though most often this condition presents when the patient notices loss of restriction or vomiting of undigested food. Weight loss results after adjustable gastric banding are a bit controversial, with some reports of 35–40% loss of excess weight and others in the 50–65% range (32). The claim that these differences can be explained by differing management of band adjustment has not been tested.

Sleeve Gastrectomy

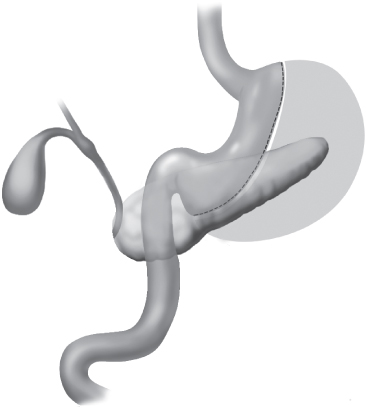

Another restrictive operation, the sleeve gastrectomy, was initially described by Marceau and colleagues in 1993 (33) as the restrictive part of the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Here, a gastric “tube” is fashioned by resecting the fundus and majority of the body of the stomach from several centimeters proximal to the pylorus to the gastroesophageal junction at the angle of His (see Figure 19-2). The resection is calibrated along a bougie on the lesser curvature to result in an 80–120 cc stomach volume. Although initially adopted as the first operative stage of the duodenal switch in very-high-risk patients (super-morbidly obese, extensive comorbidities), early results suggest that in the appropriate population this may suffice as the sole weight loss procedure adequate to achieve satisfactory weight loss without further surgical intervention.

Similar to the adjustable gastric band, the sleeve gastrectomy restricts the volume of food eaten. Although more involved surgically than the adjustable gastric band, the sleeve gastrectomy as a stand-alone, weight-loss procedure appeals to those who might have an aversion to implantation of a foreign body and its potential consequences. In contrast to the band, however, the sleeve gastrectomy is not reversible. Although there has been concern that the risk of gastric leakage and bleeding may be higher with this procedure than other bariatric procedures, more recent data suggest that the risk of complications is similar to that of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Still evolving, sleeve gastrectomy is currently used as either the first of a two-stage procedure or as a definitive procedure. While long-term results are not yet available, early weight loss results with sleeve gastrectomy are variable. Many studies found weight loss to be similar to that of the adjustable banding procedure, however as less severely obese patients are undergoing the procedure the weight loss results are higher (34).

Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass

The most popular and widely recognized operation for weight loss in the US is the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (pronounced “roo-en-why”), depicted in Figure 19-3.

First described by Mason and Ito in 1967 (35), this is truly a combination procedure, where a small-volume gastric pouch (the restrictive component) is surgically connected to a variable-length section (“limb”) of the upper small intestine (jejunum) (See Figure 19-3). Another section of small intestine, which starts from the stomach and includes the duodenum and proximal jejunum, carries the biliopancreatic secretions. The two intestinal sections meet distally (at the crotch of the “Y”) to finally allow mixing of ingested matter and digestive secretions in the small intestine.

Although no intestine is removed, a certain amount of absorptive capacity (depending on the limb lengths created) is “bypassed,” thus potentially limiting absorption (though in proximal gastric bypass, calorie absorption is minimally affected and change in hormonal responses to food is likely an important additional mechanism of weight loss) (29).

Patients and providers often choose the gastric bypass because it is initially not as dependent on patient compliance for success. Certainly patients must modify their eating habits to accommodate a smaller gastric pouch, and many patients experience “dumping syndrome” after ingestion of simple carbohydrates, but the malabsorptive component can offset some excess calorie intake and dumping helps create an aversion to sweets. Dumping symptoms may include sweating, flushing, abdominal cramps, lightheadedness, nausea and diarrhea. The rate of weight loss is also greater after a gastric bypass than after other types of bariatric surgeries, with many patients reaching their “goal” weight within a year of the surgery. Published results with gastric bypass document 70% loss of excess weight at 1–2 years after surgery with 14-year results of 50% loss (36).

The price to pay for this greater chance of success might be a higher complication rate (see Box 19-3). Many large studies report an overall complication rate of up to 10%, or more (37). Despite advances in surgical technique and postoperative management, and careful patient selection, the mortality rate has not improved beyond the 0.3–0.6% level. The most frequent causes of this unfortunate consequence are sepsis secondary to leakage of intestinal contents and pulmonary embolism. One large case series reported that anastomotic leaks are more common in the laparoscopic as opposed to the open surgical procedure (4.2% vs. 2.3%) (38). Other case series have shown lower rates, and suggest that a surgeon’s experience plays a significant role in this complication. Additional potential complications specific to the gastric bypass are shown in Box 19-3. Of course, the general risks of abdominal surgery also apply, including infection, bleeding, deep venous thrombosis, development of hernias, and future adhesive bowel obstruction.

Box 19-3 Possible Complications of the Gastric Bypass

- Anastomotic leaks—leak of contents at the sites of connections of the intestinal sections

- Anastomotic stricture—contraction of the tissues at the sites of connections of the intestinal sections

- Gallstone formation

- Pancreatitis

- Malabsorption

- Marginal ulceration

- Pulmonary embolism

- Sepsis—infection

Biliopancreatic Diversion

The most malabsorptive procedure in contemporary practice was first described in 1979 by Scopinaro (39, 40) as the biliopancreatic diversion. Though similar to the gastric bypass, where there is a “Y” configuration of the intestine, it differs from the gastric bypass in several respects. In contrast to the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the distal stomach is actually removed, but much more of the stomach volume remains (about 100 cc or more). The length of small intestine available for absorption (the common channel) is much shorter than with the bypass, severely limited to about 75–150 cm. The larger gastric pouch of a biliopancreatic diversion provides less restriction, but this is offset by bypassing significantly more intestine, thus limiting absorption. In a modification known as the duodenal switch (Figure 19-4), a sleeve gastrectomy is performed and a duodenoileostomy is created to route ingested contents to the alimentary limb (first described by Marceau in 1993) (35). This variation greatly diminishes the unpleasant “dumping syndrome” by maintaining the pylorus; in addition, it has been shown to decrease the incidence of marginal ulceration.

Patients who choose or are steered toward this procedure tend to be heavier (BMI > 50), as the overall weight loss has been shown to be greatest with this type of procedure. Additionally, patients enjoy the consumption of greater quantities of food. On the other hand, these patients must be extremely diligent in their vitamin and mineral supplementation and protein intake, as they are at greatest risk of malnutrition given the very short absorptive area remaining in their intestinal tract. Most of them also experience annoying side-effects like excessive gas and an unpleasant body odor. Finally, unlike the adjustable gastric band or even the gastric bypass, this operation is impossible to reverse completely, as a large portion of the stomach is removed.

Complications following biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) (41) are similar to those seen with gastric bypass, including anastomotic problems such as leaks (0–2%). A complication unique to the BPD/DS is a duodenal stump blowout, where the cut end of the duodenum remaining after the gastric resection leaks, most likely resulting from backpressure from a distal obstruction, or from staple line failure. Gastric retention (6–9%) and gastric perforation (<1%; again, likely resulting from staple line failure) have also been described. Mortality after BPD/DS is also significantly higher than for the gastric bypass or band procedure, ranging from 0% to 7.6% (42, 43).

As implied in the preceding discussion, with greater potential risk comes greater reward in terms of weight loss. In a large comparative overview of 14,964 patients, Van Hee (2004) describes a 48.6% excess body weight loss in adjustable gastric banding patients, a 68.6% excess body weight loss in gastric bypass patients, and a 76.7% reduction in excess body weight with the BPD/DS at one year (37). Sustained weight loss can also be achieved; Hess and Hess (1998) noted a 70% excess body weight loss at follow-up approaching eight years in BPD/DS patients (44).

It is important to recognize that, despite the potential risks of any of these procedures, these patients are seeking surgery for improvement in their overall health as well as weight loss. Multiple comorbidities have been shown to improve or even resolve after weight-loss surgery. The metabolic syndrome, consisting of the constellation of hypertension, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, and obesity, is reversible in up to 98% of patients one year postoperatively (45). Many case series confirm the impressive results of weight-loss surgery. In a meta-analysis of 136 studies, consisting of more than 22,000 patients, Buchwald and colleagues (2004) reported that type 2 diabetes (as demonstrated by elevated hemoglobin A1C and fasting glucose levels) improved in 83% of patients (40). Hypertension resolved completely in 67.5% of patients, and improved (evidenced by a reduction in medication required to control it) in 87%. Obstructive sleep apnea was resolved or improved in 94.8% of patients, and hyperlipidemia improved in 96.9% of patients. More variable results were seen with gastroesophageal reflux, osteoarthritis, urinary stress incontinence, pseudotumor cerebri, and other comorbidities, but in general these conditions also improved in the majority of patients.

Nutritional Management and Follow-Up

Pre-Surgery Guidelines

Research indicates that a small amount of weight loss over a short period of time can significantly reduce liver size and the amount of intra-abdominal adiposity, causing less intra-operative blood loss and fewer complications (46). In some programs, patients are placed on a diet preoperatively, 2–4 weeks prior to surgery, in order to encourage weight loss and reduce the size the liver.

Behavior Modification

Patients are told that weight loss surgery is a “tool” that will aid them in losing weight. They will still need to follow certain nutritional guidelines and exercise regularly in order to achieve and maintain a healthier weight. The patient must understand that undergoing surgery requires a lifelong change in habits. Helping patients to understand why surgery requires a change in eating behaviors and motivating them to make these changes are critical to their success. The diet is slowly progressed during the first few weeks after surgery, from clear liquids to puréed foods, then to soft foods, and finally to foods of regular consistency. For the most part, complications can be prevented through proper education and compliance with changes in eating habits.

Post-Surgery Guidelines

The postoperative diet begins with a clear liquid diet. This includes water, broth, diet gelatin, and decaffeinated tea. Once a patient is tolerating a clear liquid diet, he or she is then advanced to puréed foods, usually between postoperative day two and 2–3 weeks after surgery, depending on surgeon preference and patient tolerance. Patients may purchase pre-blended foods such as baby food or they can prepare their own purées. Freshly blended foods of their own liking may help to increase compliance during this challenging period of change. Blenders or food processors may be used to make meals in larger amounts, and then the puréed food can be placed into individual small jars or ice cube trays to be frozen and consumed at a later time. Adjustable band and sleeve gastrectomy patients remain on a puréed diet for two weeks. This enables the swelling to subside, sutures/staple line to heal and allows scar tissue to form around the band to prevent slippage or an obstruction. It is suggested that gastric bypass and BPD-DS patients remain on a puréed diet for three weeks. This also permits the swelling to subside and avoids vomiting, which can disrupt the staple line.

The diet is gradually advanced to a soft, solid consistency, and solids are introduced according to the patient’s tolerance. One of the first behavioral changes that must be learned is eating slowly and chewing food to a mushy consistency. If patients eat too fast or do not chew their food well, they may overfill and vomit. Many patients fear vomiting and take their time eating.

Patients are encouraged to measure and weigh their food so they can be aware of how much they are eating. It is recommended that they do not spend more than 20 minutes eating a meal, because this allows enough time for patients to feel satisfied without overfilling (47). Food that is more solid and dense will allow the patient to feel satiated for a longer period of time. Patients should be encouraged to eat every 2–4 hours, depending on the type of surgery, while awake. To ensure greater weight loss, patients should refrain from eating high-calorie foods.

Mean pre-surgery energy intake has been calculated to be 4,355 kcal/day (43). Daily postoperative intakes are about 100–200 kcal in the hospital, 400–600 kcal in the first six weeks, 600–800 kcal for the next three months, 800–1,000 kcal at six months, and 1,000–1,200 kcal at 12 months after surgery. Bothe and colleagues recommend long-term compliance with a diet of approximately 800–1,200 kcal a day as desirable (47–50).

Protein

An emphasis is placed on foods that are high in protein. Protein aids in wound healing, maintains lean body mass, prevents weakening of the immune system, provides a feeling of satiety, and prevents malnutrition. Animal foods have a high biologic value and should be preferentially consumed (51). Patients should realize that, because the stomach will fill rapidly, they should select and consume foods of primary importance first. If protein is not chosen first, they will have difficulty eating enough of this nutrient. A high-protein liquid supplement is recommended to help meet protein needs in the early post-operative period. We recommend that BPD/DS consume 80–120 g of protein daily. Other weight-loss surgery patients are recommended to consume 60–80 g of protein daily.

Hydration

Patients are advised to drink 48–64 oz of fluid per day. From the outset, separation of liquids and solids is encouraged; hence, patients are instructed to consume enough liquids between their meals to quench their thirst and prevent dehydration. Separation of liquids and solids is important for maintaining satiety because liquids empty much faster from the gastric pouch than solid foods and in addition can wash solid foods out of the pouch. It is recommend that gastric bypass patients wait 30 minutes after eating to drink. The LAP-BAND® patient is informed to wait one hour after eating to consume liquids. All beverages should be low-calorie or non-caloric. High-calorie liquids, such as alcohol, milkshakes, sweetened beverages, and fruit juices, are strongly discouraged to prevent weight regain. Patients are educated on the negative consequences of drinking while they eat.

Supplements

Because this patient population is not able to consume sufficient nutrients from the foods they eat, vitamin and mineral supplementation in quantities greater than the DRI (dietary reference intake) is strongly recommended (52). In certain circumstances, oral supplements may not be sufficient and intravenous or intramuscular supplementation may be necessary.

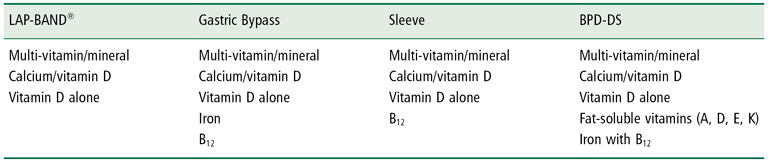

We recommend that adjustable banding and sleeve gastrectomy patients consume a multi-vitamin and mineral supplement, and the DRI for calcium and 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily. As there is no change in absorption, the DRI should be adequate, however additional B12 is recommended for sleeve gastrectomy patients as well since decreased production of hydrochloric acid hinders the release of vitamin B12 from protein. In contrast, malabsorptive operations generally bypass the duodenum and a significant portion of the stomach. Intrinsic factor and acid from the stomach are required for normal absorption of B12 and the duodenum is the primary site for iron and calcium absorption. It is therefore recommended that the gastric bypass patient daily take a multivitamin and mineral supplement, 1.5 times the DRI for calcium, 500 mcg sublingual B12, and 150 mg of elemental iron. Vitamin B12 may also be taken as a 1 mg intramuscular injection monthly. In addition, gastric bypass patients are recommended to take 50,000 IU dry vitamin D3 weekly.

The BPD involves bypass of most of the small intestine with a short common channel of up to only 75–150 cm where food mixes with bile for absorption of fats. The BPD patient is therefore educated to consume two multivitamins, twice the DRI for calcium, additional fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), and 150 mg elemental iron that contains Vitamin B12 daily (see Table 19-2). BPD patients are also recommended to take 50,000 IU dry vitamin D3 weekly. All patients are informed that vitamins and minerals are needed daily for life to prevent nutritional deficiencies. Although daily supplementation is recommended, this alone does not guard against deficiencies. Yearly measurements (or semi-annually with BPD) of a patient’s levels of these nutrients is the best way to monitor and prevent deficiencies.

Table 19-2 Recommended Supplementation

Post-Surgery Complications

Bowel Changes

Constipation and diarrhea can occur with weight-loss surgery. Constipation can occur with iron supplementation, and a reduction in calories, fluids and fiber. Diarrhea, or loose stools, is usually a side-effect of intestinal bypass, especially if the diet is high in fat or carbohydrates. BPD patients usually have 2–6 liquid/soft bowel movements daily. The stool can be gaseous and foul-smelling. This can occur from a combination of fat and carbohydrate maldigestion, nutrient malabsorption, and bacterial overgrowth (53, 54). Diet modification can reduce these symptoms. Probiotics, over-the-counter internal deodorants, pancreatic enzymes, and prescription antibiotics may be recommended to treat these symptoms.

Vomiting

Vomiting can be caused by eating too much or too fast or drinking fluids with meals. Gastric bypass patients may experience vomiting if they have excessive narrowing at the stomach and intestinal junction. Balloon insertion and dilation may be necessary to open the passage. Adjustable band patients may experience vomiting if the band is too tight or the band has slipped. Frequent vomiting is not a normal result of bariatric surgery and should be investigated; it has been associated with acute vitamin B1 (thiamin) deficiency and Wernicke’s syndrome, which can result in irreversible neurological deficit.

Food Intolerance

Some patients have difficulty tolerating certain foods. In our experience, the most common food intolerances are red meat, white meat poultry, non-toasted bread, and white rice. Patients with a tight band or stoma may not tolerate these foods, and will need to avoid them to prevent emesis or obstruction. Fibrous vegetables like asparagus and leeks may also be difficult to tolerate as can the skin on some fruits and vegetables. The former may need to be avoided and the later may need to be peeled.

Dumping Syndrome

Dumping syndrome is characterized by both gastrointestinal and vasomotor symptoms, including postprandial fullness, cramping abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, dizziness, flushing, palpitations, and an intense desire to lie down (55). Some of these symptoms may occur after consuming sweet foods or liquids and drinking while eating. Operations like the gastric bypass that bypass the pylorus, cut the vagus nerve, speed emptying of the stomach, or impair accommodation of ingested food can lead to this disturbance (56).

Hormonal changes in response to food intake have also been implicated in dumping syndrome. Most patients with dumping syndrome can be managed with dietary modification. In extreme cases where patient actually loses consciousness, further evaluation is warranted.

Nutritional Complications

Nutritional complications are of significant concern and early recognition and treatment are essential to minimize the chance of an adverse outcome. Iron deficiency can lead to anemia in up to one third of menstruating women after gastric bypass. Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to permanent neurological damage. Vitamin D deficiency, present in more than half of severely obese patients even before surgery, results in poor calcium absorption which, in conjunction with the bypass of the duodenum, can result in bone demineralization.

Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies

Bariatric surgery can promote weight loss both by restriction and malabsorption of nutrients. Inadequate body reserves, poor dietary intakes, inadequate supplementation, and noncompliance with taking the recommended supplements can all contribute to nutrient deficiencies (48, 57–60). Available data suggest that deficiencies can occur as early as within the first three months postoperatively (61). Although daily supplementation is recommended, this alone does not guard against deficiencies.

A purely restrictive operation brings about a lower incidence of serious nutritional consequences than one that uses malabsorption to bring about weight loss (57, 62). Deficiencies of vitamin B6, vitamin B12, riboflavin, folate, thiamin, calcium, zinc, and protein have been documented with restrictive procedures (48, 57, 58, 63–65). The decrease in food volume resulting from an altered pouch size, stoma size, and pouch-emptying rate following restrictive operations will likely lead to a corresponding reduction of nutrient ingestion (63, 66). This is of concern, especially in the early postoperative period, during which time it is unrealistic to expect the patient to consume adequate nutrients to meet the DRIs (47, 63).

Deficiencies associated with malabsorptive operations occur much more frequently than those after restrictive procedures. Many vitamins and minerals are absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum, the area that is bypassed. Fat malabsorption can also lead to deficiencies of the fat-soluble vitamins, A, D, E, and K. Deficiencies in thiamin, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, folate, and iron have also been documented with these procedures (48, 54, 62).

Hypoalbuminemia

Incidence of protein deficiency has been reported to be as low as 5% and as high as 30% following a malabsorptive operation, and is less common with gastric bypass than with biliopancreatic diversion (40, 54). The size of the gastric pouch, the length of the alimentary limb, and, most importantly, the length of the common channel all affect protein absorption and may contribute to a deficiency. Initially, a period of nutritional support may be all that is needed, but recurrence will likely require revisional surgery.

Importance of Follow-Up

Long-term follow-up care is repeatedly emphasized to patients. In our practice, we strongly recommend that all of our patients follow up at two and five weeks after surgery. Gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy patients are then recommended to follow up at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, and annually thereafter. BPD patients should follow up every six months. Patients who have undergone adjustable gastric banding should follow up on a more frequent basis, monthly in our practice for the first year for appropriate adjustments, quarterly for the second year, and yearly afterwards.

The need for postoperative nutritional care of weight-loss surgery patients cannot be overemphasized. This responsibility includes educating, counseling, encouraging, and supporting the patient through the surgical weight-loss experience. At each visit, the dietitian should review the patient’s food and beverage intake, supplement regimen, and activity level, and evaluate his or her weight loss in relation to individual goals. Blood is drawn for laboratory tests at 3, 6, and 12 months, and on an annual basis thereafter (see Table 19-3). If deficiencies appear, lab tests should be done more frequently.

Table 19-3 Recommended Post-Op Lab Studies for Different Procedures

| LAP-BAND® (routine lab work to be done at 6 months, 1 year, annually) Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (glucose, electrolytes, fluid balance, kidney and renal function) CBC (white blood cells, platelets, red blood cells) Lipid Panel (Total Cholesterol/HDL/LDL/VLDL/TG) Intact parathyroid hormone, PTH Vitamin D25 hydroxy Gastric Bypass (routine lab work at 3 m, 6 m, 12 m, 18 m, 2 years, annually) Comprehensive Metabolic Panel CBC Iron/Ferritin/TIBC Lipid Panel (Total Cholesterol/HDL/LDL/VLDL/TG) Vitamin A; Vitamin D25 hydroxy Intact PTH B12 Folate Zinc BPD-DS (routine lab work at 3 m, 6 m, 12 m, 18 m, 2 years, and every 6 months afterwards) Comprehensive Metabolic Panel CBC Iron/Ferritin/TIBC Lipid Panel (Total Cholesterol/HDL/LDL/VLDL/TG) Vitamin A Vitamin D25 hydroxy Vitamin E Vitamin K Intact PTH B12 Folate Zinc

|

Conclusion

At present, most severely obese patients are not likely to choose to undergo surgical treatment. Unfortunately, there are no non-surgical options that are remotely as effective for long-term weight loss in this population, and even modern, minimally invasive surgery carries some significant risk. For patients who do present for surgical treatment, careful evaluation, education, preparation, choice of operation, and consistent follow up will lead to the best outcomes. The transformation seen in patients who achieve control over their eating and maintain significant weight loss with these procedures is remarkable. The burden of severe obesity is best understood in light of the contrast between the patient before and after such a metamorphosis.

Summary: Key Points

- The prevalence of severe obesity has increased to over 10% in the US.

- Severely obese individuals face a 2–12-fold increase in mortality with increasing BMI above 30 kg/m2 and a greatly increased risk of morbidity and reduced quality of life.

- Bariatric surgery results in the restriction of food consumption and/or malabsorption of nutrients. It is an effective and enduring treatment for severe obesity, yet not all obese patients are appropriate candidates for surgery.

- The 1991 NIH guidelines specify that candidates for bariatric surgery must have 1) a BMI of 40 kg/m2or higher, or a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher along with significant obesity-related comorbidity; and 2) demonstrated dietary attempts at weight loss, which have been ineffective. (Note that the LAP-BAND® Adjustable Gastric Banding System was approved by the FDA in 2011 for use in patients with a BMI as low as 30 kg/m2.)

- Preoperative evaluation of all eligible candidates for surgery should include 1) medical and dietary history, 2) identification of comorbid conditions, 3) physical examination, 4) full blood chemistry panel, 5) thyroid panel, 6) blood count, and 7) electrocardiogram. Patients undergoing a malabsorptive procedure should have a detailed assessment of vitamin and mineral status and may require preoperative repletion.

- All bariatric surgical procedures are commonly performed using either laparoscopic or open approaches. The four most common procedures are 1) laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, 2) sleeve gastrectomy, 3) Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and 4) biliopancreatic diversion.

- Nutritional and behavioral management prior to surgery and postoperatively depends on the severity of obesity, the bariatric procedure selected, and individual patient characteristics, such as the presence of comorbid conditions and nutritional status.

- Potentially serious post-surgery complications include bowel changes, vomiting, food intolerance, dumping syndrome, and nutritional deficiency; ongoing postoperative follow-up, careful nutritional monitoring, and support of behavioral changes are needed.