29 | Syringomyelia |

| Case Presentation |

History and Physical Examination

A 47-year-old Caucasian woman presented with progressive hand numbness, loss of dexterity, and gait instability. There were no inciting events or antecedent trauma. The symptoms progressed in a gradual manner over 4 months causing her to lose gainful employment as a transcriptionist. In particular, the patient noted a loss of temperature sense, which had resulted in several burns to her hands while cooking.

Physical examination revealed a positive Hoffmann reflex bilaterally with hyperreflexia in both lower extremities. There was no motor weakness on formal testing, but her gait was wide based. Sensory examination revealed diminished temperature and pain sensation in the trunk and lower extremities.

Radiological Findings

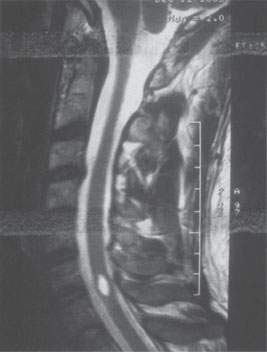

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine was obtained that showed a cystic mass within the spinal cord at C6-7. The cyst had T1- and T2-weighted signal qualities similar to cerebrospinal fluid (Fig. 29–1). Follow-up MRI with and without intravenous gadolinium contrast showed no evidence of intramedullary neoplasia, and there was no extrinsic spinal cord compression or Chiari malformation. In addition, there was no evidence of hydrocephalus on brain MRI.

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with an idiopathic spinal cord syrinx with physical findings consistent with spinal cord dysfunction at the affected level. There was no evidence of a compressive or intrinsic spinal cord lesion, which is the most common cause of syringomyelia.

Treatment

The patient underwent surgical intervention under continuous electromyographic (EMG), somatosensory, and motor-evoked potential monitoring. Following a laminotomy at C6-7 intraoperative ultrasonography was used to ensure proper lesion localization. A durotomy was then performed and the spinal cord appeared grossly normal, without evidence of subarachnoid scarring, adhesions, or blocks. A midline micromyelotomy was then performed and the syrinx cavity opened. The cyst fluid was straw colored and sent for cytology, which was unremarkable. A 1 cm long fenestrated Silastic catheter was then used to shunt the syrinx to the subarachnoid space. This catheter was sewn to the neighboring pial membrane with a 7-0 nylon suture. Intraoperative ultrasonography confirmed a diminution in cyst size.

Figure 29–1 A 47-year-old woman with an idiopathic cervical syrinx causing symptoms of myelopathy.

| Background |

Definitions

Syringomyelia is the term used to describe dissection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the ependyma to form paracentral cavitations within the cord. This should be distinguished from hydromyelia, which is used to describe simple distension of the ependymal-lined central canal. Distinction between these two conditions is often impossible on imaging studies and is often difficult to establish even after histological studies are performed.1 Therefore, the term syrinx is used to describe any pathological CSF-containing cord cavity, whether or not it is in continuity with the central canal.2

Epidemiology

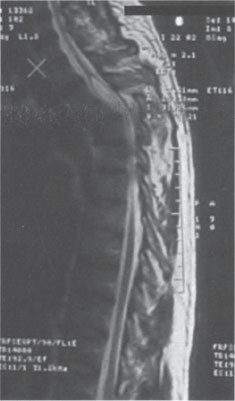

The most common etiology of syringomyelia in the cervical spine involves abnormalities of the hindbrain (Fig. 29–2). In 1891, Chiari described a series of hindbrain abnormalities found on autopsy material.3 In his report, Chiari noted that some patients with hindbrain abnormalities had dilatation of the central canal, whereas others had intramedullary cysts. Three years later, Arnold described similar findings in a single patient with myelodysplasia.3 Although this eventually led to the term Arnold-Chiari malformations, the preferred terminology for these malformations today is Chiari malformations.4 More than half a century later, we learned that Chiari malformations can exist with or without associated syringomyelia.5

Figure 29–2 Chiari I malformation with herniation of the cerebellar tonsils below the level of the foramen magnum. A cervical syrinx results from the disruptions in the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid.

Specifically, the Chiari I malformation describes downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils into the cervical canal below the level of the foramen magnum. Syringomyelia is present in 20 to 40% of all patients with a Chiari I malformation. If consideration is given to only symptomatic patients, the occurrence of an associated syrinx is even higher, ranging from 60 to 90%.6,7 The cervical spine is the most common site, although patients with Chiari I malformations can have lesions that involve the entire cord. An isolated syrinx in the thoracic cord is uncommon.5

The Chiari II malformation is a complex anomaly with manifestations that involve the skull, dura, hindbrain, midbrain, CSF spaces, and spine. This malformation is seen in virtually 100% of patients with myelomeningoceles. Hydromyelia is present in 30 to 75% of these patients. Syringomyelia often coexists and is seen in ~20% of these cases.2

Trauma is another major etiology of syringomyelia in the cervical spine (Fig. 29–3). The exact incidence of posttraumatic syringomyelia is unknown, but MRI has increased the recognition of the condition.8 Symptomatic posttraumatic cystic myelopathy, syringes, or cystic cavitation of the spinal cord occurs in up to 3.2% of spinal cord injury patients.9 Others have reported an even higher incidence of cysts based upon MRI studies, which include asymptomatic patients.10 The time span between injury and the onset of symptoms has been reported to range from 2 months to 30 years.9 In one series, the mean time to presentation was 101 months in patients with incomplete injury as compared with 39 months in patients with complete injury.11 In another series, onset of posttraumatic syringomyelia was earlier with cervical and thoracic injury levels and with increased patient age.12

Figure 29–3 Thoracic cord burst fracture causing spinal cord injury followed by delayed, progressive cystic cavitation. Note how the cyst ascends above the level of the injury, causing progressive loss of neurological function.