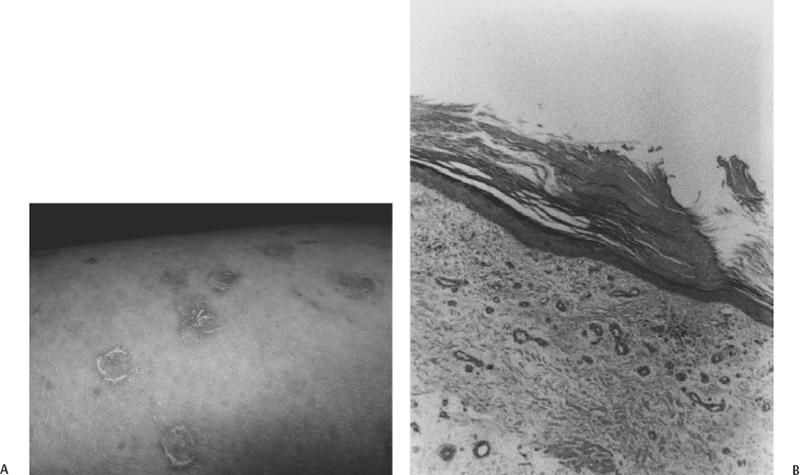

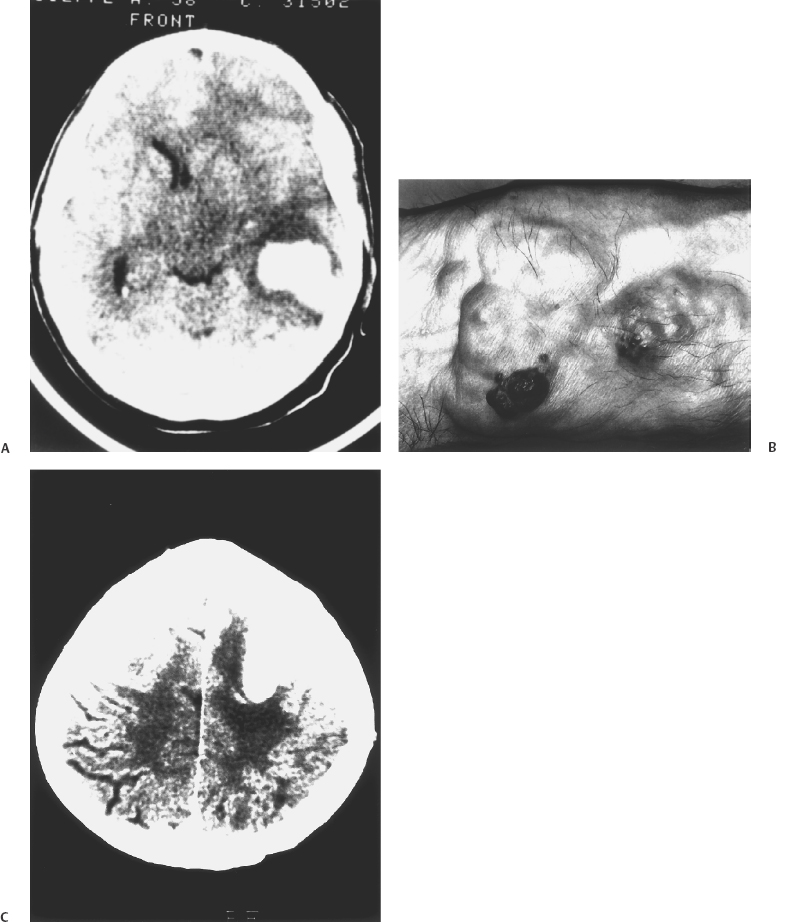

6 Eugenio Pozzati Cavernous malformations (CMs) or cavernous angiomas (CAs) or cavernomas are encountered by the neurosurgeon throughout the central nervous system, in the orbit, vertebral bodies, and epidural spinal space. Cerebral CMs (CCMs) occur in two forms: sporadic and familial. Although the sporadic, single form was believed to be preponderant, the familial form is now being diagnosed with increasing frequency and constitutes up to 50% of cases. It is characterized by an autosomal dominant mode with variable expression and incomplete penetrance, by multiple lesions, and by the de novo appearance of new malformations at a rate of 0.2 to 0.7 per year.1 The concept of CM is evolving. CM is usually considered a vascular malformation, with its basic endothelial structure arranged in closely packed sinusoids without intervening parenchyma, but some peculiarities (growth, neoangiogenesis, and de novo appearance)2 may cause this lesion to resemble a hamartoma. Furthermore, the possible occurrence of CMs at multiple levels (brain, eye, skin) can support their inclusion among the phakomatoses, or hereditary disorders with cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic manifestations.3–6 It has been correctly suggested that familial CMs might represent a forme fruste of a neurocutaneous disorder in which the cutaneous and ocular disturbances have incomplete expression or are not fully recognized.7 The combined occurrence of familial CMs inside and outside the CNS (eye and skin in particular) has always been considered exceptional, but the increasing number of reports leads us to revise our opinion. Two different situations exist: (1) widespread occurrence of inherited CMs in multiple organs and tissues (brain, eye, skin, and liver), which we may refer to as systemic CMs and consider as a phakomatosis; and (2) participation of CMs in a sporadic vascular disease, which may show prevalent segmental involvement of several tissues (skin, vertebra, and spinal cord) throughout an entire dermatome. Wider multiorgan involvement has also been reported (kidney, heart, and spleen), but it constitutes an absolute rarity.8 Similarly, diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis represents a rare, and often fatal, disease characterized by multiple cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas in the liver, lungs, intestine, and central nervous system. Death generally results in the newborn from hemorrhages or cardiac failure.9 The coexistence of CMs with a complex segmental maldevelopment has been reported in a family with systemic CAs (brain, skin, retina, and liver) in which two relatives had terminal transverse defects at the mid-forearm.10 The prevalence of systemic CMs is unknown, but it grossly parallels the availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the increasing knowledge of the familial form. Some observations are necessary regarding the genetic origin and for better understanding of systemic CMs. Three distinct loci are associated with familial CMs: CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3 are located on three chromosomal loci 7q, 7p, and 3q, respectively, indicating genetic heterogeneity. Mutations in the KRIT1 (KREV1 interaction trapped 1) gene, a binding protein with tumor suppressing activity, are responsible for CCM111 and have been demonstrated in patients with associated CMs of the retina12 and with hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformations (HCCVMs),13,14 which expand the phenotypic spectrum of the disease.15 KRIT1 plays an important role in cutaneous, retinal, and cerebral vascular development. The occurrence of CMs in various organs is not coincidental but corresponds with the effects of this mutation at these levels.12 Some types of cerebrovascular malformations (telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations in particular) are part of well-known neurocutaneous vascular disorders (Sturge-Weber disease, Rendu-Osler disease, Louis-Bar syndrome, Wyburn-Mason syndrome, and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome) characterized by their association with peculiar cutaneous stigmata.5 Systemic CMs are not yet considered in the usual classification of these diseases5 and represent an ill-defined but distinctive neuro-oculo-cutaneous syndrome, with changeable phenotype and possible overlapping with other neurocutaneous vascular disorders and phakomatosis (von Hippel-Lindau disease in particular). Whereas the cutaneous and ocular features of systemic CMs are essentially benign, the cerebral localization is sometimes the origin of significant neurologic disability. Since the original report of the first case of familial intra-and extraneural CAs,16 other observations of associated skin, retina, and brain cavernomas have been published by Weskamp and Cotlier,17 Gass,6 Schwartz et al.,18 and Dobyns et al.,3 who recognized the autonomy of the disease and suggested that this complex might represent a true phakomatosis. The triad may be incomplete, with cutaneous or ocular participation in the disease being inconsistent. The varied location pattern probably represents one entity with ubiquitous lesions.19 The affected families may differ in the distribution of their CAs, but it seems incorrect to split these families into subcategories.4 The involvement of the different organs may occur several years apart: The precise follow-up of the peripheral localization (eye and skin) may lead to an early diagnosis of the central lesions in family members.20 In the systemic disease, cerebral CMs have the usual conformation, but the histopathology of the cutaneous vascular lesions may be an “equivalent” and differ from the classic cavernomatous structure. Dermatologists should be aware of the protean manifestations of the skin lesions and delve deeper into the screening of their patients for a timely diagnosis of the cerebral disease. Various cutaneous vascular lesions are associated with familial CCMs, and their number is growing, although some terms are probably synonymous: cherry angiomas, blue rubber bleb nevi, angiokeratomas, true CAs, and recently described HCCVM. The simple association between familial cerebral and cutaneous CAs has been rarely reported.21 The cutaneous CA appears as a purple, minimally elevated papule not blanching on compression. Similarly, cherry angiomas have been described in families with CCMs,22 but the relevance of this association is unclear because of the common occurrence of skin lesions. Recently, an association between autosomal dominant CCMs and a distinctive HCCVM has been reported in some families with mutation of KRIT1,13,14 suggesting that these lesions are based on a common genetic mechanism. These crimson-like cutaneous lesions were mainly located in the lower limbs and were predominately of capillary type with a venular component in association with an overlying hyperkeratotic epidermis.14 This distinctive cutaneous vascular malformation was observed in 4 of 57 French families with CCMs indicating a non-negligible occurrence and representing a first indication of the extent of this association. In families in which these lesions coexist, all members who manifest HCCVMs also have CMs14 and the penetrance of the cutaneous lesions co-occurring with CCMs is around 40%. Furthermore, this cutaneous phenotype seems to be correlated with a particular molecular alteration found in the KRIT1 gene.14,15 The association between CCMs and HCCVMs is relatively uncommon but probably underdiagnosed. We encountered a patient with familial HCCVMs who, only after 20 years and a long history of epileptic seizures, had a diagnosis of frontal cavernoma (Fig. 6-1). She also had a hepatic cavernoma, and her daughter had renal and hepatic cavernomas, indicating an unreported extension of the phenotype of this association. In addition, these cutaneous lesions were extremely sensitive to sun exposure, suggesting a inherited origin of the disease consistent with biallelic loss of function favored by ultraviolet radiation.22 Figure 6-1 (A) This 58-year-old woman with epileptic seizures had a cavernous angioma of the left frontal lobe (not shown). The photograph is of the patient’s calf showing multiple crimson-colored macules with a pinkish discoloration of the skin. Her grandfather had the same skin lesions. (B) Photomicrograph of the cutaneous surgical specimen showing hyperkeratosis associated with dilated vessels in the upper dermis consistent with hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformation (HCCVM) (hematoxylin and eosin, magnification × 25). (Courtesy of Dr. R. Davalli, Dermatologist, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy.) A cavernous angioma was found in the liver. The patient’s daughter had cavernous angiomas in the liver and kidney. Cutaneous CMs may also be associated with other types of intracranial vascular malformations. Leblanc et al.,23 reporting on a hereditary neurocutaneous angiomatosis characterized by the coexistence of vascular nevi (generally CA) with cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) and venous malformations, noted a preponderance of male patients and suggested a possible hormonal influence on the expression of the gene. Nonvascular cutaneous lesions may be sometimes associated with inherited CCMs. Café-au-lait skin lesions typical of neurofibromatosis were associated with widespread cerebral and spinal CMs in a patient with a genetic alteration in KRIT1/CCM1, adding to the range of skin lesions found in familial CMs.24 Similarly, we observed a 40-year-old woman with multiple and de novo cerebral CMs, possible familiality (a daughter had epileptic seizures), a myriad of café-au-lait lesions, and a cutaneous angioma of the inferior eyelid irradiated in infancy. Overlapping manifestations of CMs and von Recklinghausen disease may also occur, but their mutual relationships are still obscure. Cavernous angioma of the retina is the third element that, with brain and skin, often completes the triad: It is an unusual vascular hamartoma that consists of an isolated sessile cluster of retinal thin-walled saccular aneurysms filled with dark venous blood.25–28 Similar to its cerebral counterpart, plasma-erythrocytic separation within the vascular spaces is common.6 The prognosis is generally good, although occasional bleeding into the vitreous and subretinal space has been described.27 The optic nerve head may also be involved, and bilateral retinal occurrence has been reported.27 Recently, Sarraf et al.19 described a family with skin, eye, and brain CMs related to a mutation at the level of the 7q locus. Similarly, Couteulx et al. reported a case of a KRIT1 mutation in a patient with retinal and cerebral CAs, confirming the genetic background of the disease.12 The possible presence of choroidal and iris hemangiomas expands the ocular spectrum of this phakomatosis.26,27 Twin retinal vessels, which may be found in von Hippel-Lindau disease as an early diagnostic sign, may also be present in familial CAs of the brain and retina.28 Associated CMs and hemangioblastomas were reported by Russel and Rubinstein,4 who suspected a common etiologic link. A family with “peripheral” von Hippel-Lindau disease and CCMs has been reported, again suggesting possible overlap between these disorders.29 An important difference between the systemic and classic forms of CMs is shown by the clinical relevance of CCMs. In the review of Dobyns et al,3 68% of the patients with cerebral and retinal CMs had neurologic disturbances and 48% of these had intracranial hemorrhage, indicating a higher risk in the systemic disease. Several stroke-related deaths have also been reported.25 These findings underscore the need for a precise diagnosis of the extraneural manifestations when evaluating patients with familial CMs. Available data seem to indicate a poorer clinical history of the cerebral lesions in the systemic form compared with pure CCMs. We treated a patient with multiple CCMs and associated angiomas of the wrist and eye. This patient required a remote eye excision due to an “ocular hemorrhage” and had two brain hemorrhages caused by the angiomas (Fig. 6-2). This is an additional example of oculoneuro-cutaneous CAs with aggressive biological behavior. Drigo et al. described a syndrome consisting of familial cerebral and retinal CAs associated with peculiar hepatic involvement.29 Such massive hepatic participation is quite unusual but again poorly defined in the usual screening of familial CAs. Although the association of cerebral and retinal CMs with hepatic involvement has until recently been considered as a chance occurrence of two unrelated diseases,15 screening of the liver is recommended in the management of multiorgan CMs. This family demonstrated genetic anticipation by manifesting seizure onset at an early age, a phenomenon already reported in CCMs,20 and indicating a decrease of age at symptom onset in an inherited disease, increased severity in subsequent generations, or both. The contribution of genetic anticipation may be very important in the clinical behavior of systemic CMs, and it should be determined whether or not it induces a progressive increase of the multiorgan involvement in consecutive generations. A recent update of this large family (P. Drigo and I. Mammi, unpublished data) disclosed the additional presence of cutaneous, epidural, calvarial, and vertebral angiomas (in particular of the atlas and axis), confirming the rare finding of a vertebral involvement in the familial disease, and the unrelenting multiorgan progression.30 Notably, some members of a family with CCMs that we are treating have peculiar calvarial thickening, which probably corresponds with an unreported angiomatous involvement of the bone. CAs are one of the most common tumors affecting the spine, and their association with familial and cerebral lesions constitutes an important implication for diagnosis and treatment of the affected patients. In addition to autonomous systemic CMs, recent observations suggest that two known vascular neurocutaneous syndromes may be associated with the presence of CMs in the CNS and orbit: Cobb disease and the blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. The blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is characterized by multiple, distinctive angiomas of the skin, mucous membranes, and gastrointestinal tract. The oral cavity, which constitutes an important clue to the diagnosis of a vascular disorder, also may be involved in the disease.4,5,31–34 The cutaneous lesion is characterized by bluish, thin-walled, soft, and compressible nevi. Pathologically, BRBNS reveals large blood-filled spaces separated by fibrous septa of varying thickness similar to a CA. Although some cases are sporadic, many patients have been described with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance.31 The risk of bleeding from gastrointestinal vascular malformations is the most serious clinical feature of BRBNS. More recently, it has been recognized that BRBNS may include cerebral and orbital vascular malformations. There is enough evidence in the literature to establish a relationship between BRBNS and developmental venous anomalies, sinus pericranii, and venous thrombosis.31 Vascular skin findings suggesting BRBNS have been recently described in one patient who presented with cerebral hemosiderosis occurring after previous hemorrhage by multiple cerebral CAs.32 Waybright et al.33 described a young man with BRBNS and cortical CAs, capillary telangiectasias, and a thrombosed AVM of the vein of Galen, representing possible overlap between the BRBNS and Rendu-Osler syndrome. In particular, mono- and bilateral orbital CAs have been described associated with BRBNS34 and with Maffucci syndrome, a rare nonhereditary disease characterized by hemangiomas and enchondromas.35

Systemic Cavernous Malformations

Systemic Cavernous Malformations

Systemic Cavernous Malformations

Cerebral and Cutaneous Cavernous Malformations

Cerebral and Retinal Cavernous Malformations

Cobb Disease and Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome

Systemic Cavernous Malformations

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree