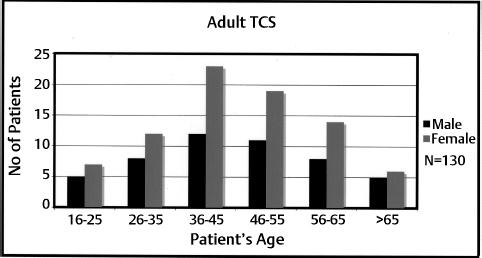

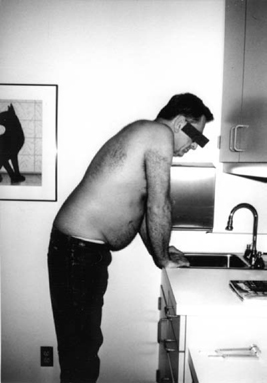

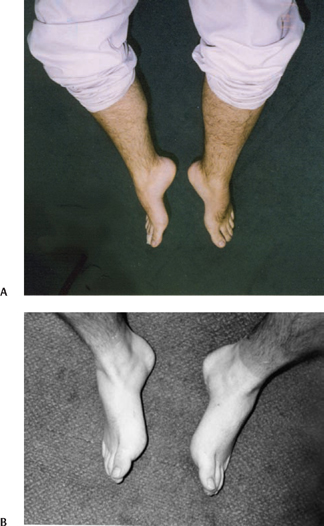

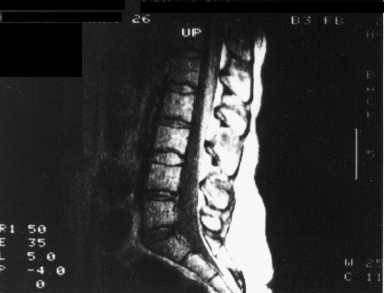

15 Tethered Cord Syndrome in Adult and Late-teenage Patients without Neural Spinal Dysraphism Shokei Yamada, Russell R. Lonser Jr. and Austin R. T. Colohan, Cheryl T. Yamada Hoffman et al should be credited with linking the term “tethered spinal cord” to patients with lumbosacral signs and symptoms associated with elongated cord and thickened filum terminale.1 Since the subsequent publishing of our report “pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome (TCS)” in 1981,2 we have sought to crystallize TCS as a distinct syndrome which corresponds to the pathophysiology.3 This chapter describes how this goal was achieved by reviewing information from patients similar to those selected by Hoffman in 1976.1 With the exception that our patients include those with TCS caused by an inelastic filum terminale, with or without cord elongation or filum thickening.3,4,5 These late teenage and adult patients have descirbed their complaints and reactions in detail, including back and leg pain, urinary or rectal incontinance and sensory changes, which allows us to clearly group their symptoms and systematically document their physical and neurological signs. Such symptoms have become important sources of information for TCS diagnosis. Research into the pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome (TCS) indicates that its signs and symptoms are associated with characteristic impairments in oxidative metabolic and electrophysiological activities within the spinal cord rather than with histological damage.1–6 This distinction is important because it may explain why untethering of the spinal cord reverses the symptoms of TCS. However, reported results of untethering surgery are complicated when patients with neural spinal dysraphism are included in adult TCS patients.7–14 To account for these variations, we grouped patients as group 1 patients with neural spinal dysraphism, such as myelomeningocele (MMC) and lipomyelomeningocele (LMMC), and group 2 patients with no evidence of these anomalies but an inelastic filum that is anchoring the spinal cord at its caudal end.3,5 Group 1 patients were known to have a certain degree of stabilized neurological deficits that progressed in adulthood (see the discussion of cord tethering category 2B), and group 2 patients presented with characteristic symptomatology only in the late teenage years or adulthood. Group 2 is the subject of this chapter, and from now on is referred to as adult TCS. In this chapter we report on symptomatic patients with strict surgical indications based on a review of their signs and symptoms and imaging studies. These patients are typical of those with TCS, and surgery was recommended regardless of the presence or absence of an elongated cord or thickened filum. Surgical procedures consisted of sectioning or resection of the inelastic filum to untether the spinal cord. Although this group of patients are included in Category 1 (true TCS) with sacral myelomeningocele and caudal lipomyelomeningocele among the visually expressed “tethered cord (or cord tethering)” patients, (See Discussion, Tethered Cord Syndrome and Various Interpretation and Prognosis), the latter two were excluded in the current series to avoid their complexity of the terminology. This report includes 130 patients (50 males; 80 females, ages ranging from 16 to 81 years as seen in the bar graph) (Fig. 15.1). Approximately 75% of these patients were originally referred for evaluation of “failed back”15 or failed back surgery syndrome.16 Each patient was subsequently diagnosed as having TCS and underwent untethering to alleviate the symptoms. Referral diagnoses included recurrent herniated disk, suspected herniated disk, osteoarthritic spondylosis, and back sprain. Twenty-three percent of these patients had a previous history of lumbar spine surgery without permanent pain relief and were categorized with failed back surgery syndrome.17 Experiences in our group5 and in others12 have confirmed that detection of the reversible signs and symptoms for true TCS18 is important for effective treatment of patients because accurate diagnosis and proper surgical untethering at an appropriate time have successfully reversed symptomatology. The following specific TCS symptoms should be identified in addition to routine physical and neurological examinations. Fig. 15.1 The bar graph shows the distribution of the number of patients in age categories. There are two noteworthy magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in the group 2 patients: (1) cord elongation and filum thickening, and more significantly (2) posterior displacement of the filum, which is consistently found in these patients, signifying that the filum travels along the concave side of the lumbosacral lordosis, to minimize spinal cord tension.5,21 Due to limited resolution, MRI or computed tomographic (CT) myelographic visualization of the location of the conus tip in relation to the vertebral level and the thickness of the filum is less accurate than the determination at surgery. For example, the caudal end of the spinal cord can be determined by identifying the exit of the lowest coccygeal nerve (100 to 150 µm diameter) from the spinal cord, particularly for the conus tip located at the L3 vertebral level. From our experience, the caudal end of the spinal cord was found at the L2–3 intervertebral space or below in 64% of the patients, and the diameter of the filum was ≥ 2 mm in 42.3% (N = 104). These data clearly indicate that the preoperative diagnosis of adult TCS must rely primarily on the symptomatology and the specific imaging feature of posterior displacement of the conus and filum that attach to the posterior arachnoid membrane (see Chapter 18). A capacious lumbosacral subarachnoid space is often associated with TCS. Cine-MRI motion pictures have been reported to show stiffness of an inelastic filum in contrast to a freely moveable cauda equina.2 Although simulating the effects of ultrasonography in infants, this technology is not universally used.22 Determination of the signs and symptoms characteristic of group 2 adult TCS patients is critical for accurate diagnosis and proper treatment. The specific features of TCS were previously described as a protocol for the diagnosis of adult TCS23 and are listed in what follows. We have found that patients who show greater than 90% of these signs and symptoms are very likely to have TCS, and an urgent MRI study is recommended. Protocol for symptoms associated with tethered cord syndrome Fig. 15.2 Because his back and leg pain was aggravated while trying to bend over slightly to wash dishes, the patient had to hold onto the edge of the sink. After untethering surgery, the patient was able to wash dishes without developing pain. Protocol for signs associated with tethered cord syndrome Fig. 15.3 Accentuated lumbosacral lordosis was noted in this tethered cord syndrome patient. Fig. 15.4 (A,B) High-arched feet associated with mild bilateral hyperextension of the metatarsophalangeal joint and flexion of the phalangeal joint in the great toes (hammertoes) were found in these patients with early tethered cord syndrome. These deformities rapidly subsided after untethering. The patient in (A) shows more pronounced high arch than the patient in (B). The tethered cord syndrome is more advanced in the former than in the latter patient. Neurological signs and symptoms and musculoskeletal deformities are tabulated in Table 15.1. Negative findings are also important for diagnosis, such as the absence of a Babinski sign or straight leg-raising pain (except for one patient with concomitant herniated disk at L5-S1). Fig. 15.5 At examination, mild but definite weakness of the extensor hallucis longus muscle was detected in this tethered cord syndrome patient, with the examiner using his little finger flexors to overcome dorsiflexion of the phalangeal joint in the patient’s great toe. The patient regained normal strength of this muscle within a few days after untethering surgery. Table 15.1 Neurological Signs and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis

| Signs and Symptoms | % |

| Muscle weakness | 94 |

| Muscle atrophy | 47 |

| Gait difficulty | 58 |

| Sensory deficit | 96 |

| Bladder dysfunction | 74 |

| Anal sphincter dysfunction | 90 |

| Hyporeflexia of some of the knee and ankle jerks | 95 |

| Scoliosis | 98 |

| Exaggerated lumbosacral lordosis | 74 |

| Leg/foot deformity/high arches | 76 |

| Hammertoes | 40 |

| Leg or foot deformities/difference in length of legs or size of feet | 3 |

Differential Diagnosis

To make a differential diagnosis of TCS, many other congenital or acquired diseases must be considered.

- Extradural lesions include acute herniated disk or recurrent herniated disk, inflammatory process of a disk, or painful disk degeneration, lateral recess syndrome or lumbar canal stenosis, epidural scar (pain due to irritation to the dura or spinal nerves) or pseudomeningocele-arachnoid cyst, and malignancy of the spine encroaching into the epidural space.

- Intradural-extramedullary lesions may produce symptoms similar to TCS, including meningiomas and schwannomas. A small schwannoma confined in the subarachnoid space needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of TCS.

- Intramedullary lesions with symptoms overlapping or similar to those of TCS include tumors, such as gliomas and ependymomas, which can be extraaxial, lumbosacral syringomyelia, multiple sclerosis, and exacerbation of poliomyelitis. Arachnoiditis or postoperative arachnoid adhesion that obliterates the subarachnoid space may result in spinal cord ischemia. For example, the authors found two cases that presented with TCS due to an encasement of the entire cauda equina with extensive arachnoid adhesion, causing lumbosacral cord tethering. After complete neurolysis of the entire cauda equina fibers, the lumbosacral cord was relaxed. Postoperatively both patients were completely free of back and leg pain and had subsidence of motor, sensory, and bladder dysfunction.

- Spine abnormalities, such as unstable lumbar and sacral spine or spondylolisthesis; lumbar facet syndrome or osteoarthritic spondylosis and ischiogluteal bursitis, trauma of vertebrae, fascia, muscle, and facet capsules also must be ruled out when seeking to diagnose TCS.

- Another complication in diagnosing TCS stems from lesions that originate outside the spinal canal. When back pain is the predominant symptom, for example, the pain may be due to TCS but it could also be due to (1) muscle spasms from physical overstress, (2) fibromyalgia, (3) peripheral nerve disorders, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, (4) peripheral neuropathy due to diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and heavy metal toxicity.

- Spine abnormalities, such as unstable lumbar and sacral spine or spondylolisthesis; lumbar facet syndrome or osteoarthritic spondylosis and ischiogluteal bursitis, trauma of vertebrae, fascia, muscle, and facet capsules also must be ruled out when seeking to diagnose TCS.

The most common area for confusion in the differential diagnosis of TCS is from a herniated lumbar or sacral herniated disk, and associated cauda equina syndrome. This diagnosis can easily be determined from the symptoms as shown in Table 15.2.

The diagnosis of TCS is clearly established with these characteristic signs and symptoms and with typical MRI findings. However, differential diagnosis of adult TCS requires special attention to three factors:

- Signs and symptoms of TCS are subtle or their progression is insidious; in fact, patients are often referred to neurosurgeons as neurologically intact.

- Acquired diseases in adults may obscure the typical signs and symptoms of TCS.

- Imaging studies must be reviewed closely to find the characteristic features of TCS.

Table 15.2 Differential Diagnosis of Tethered Spinal Cord Syndrome

| Herniated Disk | Tethered Cord Syndrome | |

| Radiating pain | + | – |

| Pain in inguinal and genitorectal area | – | + |

| Aggravated by coughing | + | – |

| Effects of 3B postures | – | + |

| Pain worse by slouching than by sitting straight | – | + |

| Pain worse on lying supine | – | + |

| Myotomal dysfunction | + | – |

| Dermatomal deficit | + | – |

| Perianal or distal hypalgesia | – | + |

| Extensive patchy hypalgesia | – | + |

| Incontinence | – | + |

| Paravertebral spasms | + | – |

| Pain on straight leg-raising test | + | – |

| Musculoskeletal deformities | – | + |

Treatment

See Chapter 21 for a discussion of conservative treatment. Here we will discuss surgical treatment

Surgical Indications

Surgical indications for adult or pediatric TCS are determined by the combination of symptomatology and imaging studies. Symptomatology includes the following:

- Aggravation of pain in the back and legs that is initiated or accentuated by repeated lumbosacral flexion and extension, particularly by special postural changes described in Signs and Symptoms

- Physical exercises that accentuate spinal curvature

- Progressive motor and sensory changes with skipped myotomal and dermatomal deficit, sometimes in sclerodermal distributions referred to bony or ligamentous structures19

- Increasing difficulties with bladder or rectal control

- Increasing lordosis or scoliosis or foot and toe deformities

The definite imaging signs of TCS are the posterior displacement of the conus medullaris and touching of the posterior arachnoid membrane by the filum;5,21 however, there are other imaging signs that suggest TCS including the following:

- A fibroadipose filum, although fat itself is not inelastic unless fibrous tissues grow together in large quantity

- An elongated spinal cord1,7–14

- A lipoma attached to the filum tip24

- A thickened filum (Hoffman)

- A capacious sacral sac, which is found in ∼50% of our TCS patients13 (Fig. 15.6)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree