16 Tethered Cord Syndrome in Adults with Spina Bifida Occulta Sharad Rajpal, Samir B. Lapsiwala, and Bermans J. Iskandar Congenital tethered cord syndrome (TCS) presenting in adulthood is an uncommon entity that can potentially become symptomatic. The management of adult-onset TCS, however, remains controversial even though the necessity of early surgery in children with TCS is well established. The long-term surgical outcome after tethered cord release (TCR) in the adult population is generally favorable because most patients report improvement or stabilization of their symptoms. In addition, the overall postoperative complication rate is low. Although special consideration should be given to older patients with a poor general medical condition, it seems reasonable to recommend early surgical treatment in patients with TCS as well as asymptomatic patients with spina bifida occulta. This chapter reviews the major publications that discuss congenital tethered spinal cord (spina bifida occulta) presenting in adulthood. Data discussing acquired tethered cord from prior myelomeningocele repair will not be addressed. Congenital anomalies of the spinal cord arise from incomplete formation of the dorsal midline structures and comprise a spectrum of malformations involving the neural tissue, meninges, bone, and skin. These malformations are divided into two broad categories: spina bifida aperta (SBA) and spina bifida occulta (SBO). SBO represents a set of “covered” spinal cord lesions that include lipomyelomeningocele (LMM), split cord malformation (SCM), meningocele manqué (MM), ectodermal inclusion tumor or cyst, neurenteric cyst, and tight filum terminale. SBO lesions are often concealed, or occult, even though coexisting cutaneous (hypertrichosis, capillary hemangioma, subcutaneous lipoma, dermal sinus, caudal appendage, atretic meningocele) or orthopedic (musculoskeletal) anomalies, including vertebrae or lower extremity manifestations are present in greater than half the cases. The absence of such external stigmata may delay diagnosis until later in life. Tethering, or stretching of the spinal cord, results from fixation of the cord by inelastic structures. Most SBO lesions cause spinal cord tethering by their mere presence; such pathophysiology is similar to that caused by scar tissue following myelomeningocele repair1 (refer to Chapters 3 and 11 on pathophysiology and on myelomeningocele and lipomyelomeningocele for details). In fact, some cases of postrepair myelomeningocele TCS may be caused by residual tandem lesions, such as a tight filum terminale or SCM, which is not recognized at the time of initial myelomeningocele closure.2 Regardless of the cause of tethering, the physiological changes that occur within the spinal cord and the resultant clinical presentation seem to be consistent, but the age of presentation can be variable. It is well established that all children with SBO require TCR to prevent neurourological deficits.3 The situation is less clear, however, in adult-onset congenital TCS, mainly because of the lack of natural history studies.4,5 We systematically reviewed the literature on adult TCS using a Medline search. Most series reported mixed data that included either mixed SBO and SBA patients or mixed adult and pediatric populations. Fourteen series of adult TCS were found, but only five reported either adult SBO-only data or presented data in a fashion that allowed the exclusion of children and SBA patients.6–9 The remaining nine series were excluded (Table 16.1). The largest SBO-only pediatric tethered cord series to date was used to compare adult and pediatric outcomes.2 Because all patients with SBO are assumed tethered, the terms SBO and TCS are used interchangeably in this chapter. Because of the paucity of data in adults, we will not attempt to subclassify our discussion of the congenital TCS according to the various spinal anomalies. Table 16.1 Reasons for Exclusion of Large Reported Series from this Review

Method and Materials

| Authors | Reason for Exclusion |

| Begeer et al28 | Mixed adult and pediatric populations |

| Huttmann et al11 | Mixed SBO and SBA data |

| Kirollos et al4 | Mixed SBO and SBA data; mixed adult and pediatric populations |

| Koyanagi et al29 | Mixed adult and pediatric populations |

| Lee et al30 | Mixed SBO and SBA data |

| Pang et al5 | Mixed SBO and SBA data |

| Sharif et al31 | Mixed SBO and SBA data; mixed adult and pediatric populations |

| Van Leeuwen et al10 | Mixed SBO and SBA data |

| Yamada et al16 | Mixed SBO and SBA data |

Abbreviations: SBA, spina bifida aperta; SBO, spina bifida occulta.

Results

Classification of Adult-Onset Spina Bifida Occulta

Congenital TCS in adulthood presents more often in females (M:F ratio 1:1.3 to 1:2.8), and patient ages can range from 18 to 75 years (mean 37 years).4,5,9,10 Although the majority of these patients present with symptoms of TCS, some are discovered incidentally (e.g., cutaneous or orthopedic anomalies that were previously unrecognized). Symptomatic patients are divided into three groups according to the classification by Pang and Wilberger5: (1) patients with no neurourological deficits, cutaneous, or skeletal anomalies in childhood, but with symptom development later in life; (2) patients with either cutaneous and skeletal deformities or stable neurological deficits in childhood but who suffer progressive neurological symptoms and signs starting in adulthood (some of these patients may have undergone corrective surgery for orthopedic, urological, or cosmetic cutaneous problems earlier in life); and (3) patients with progressive neurological symptoms and signs starting in childhood and continuing into adulthood.

Approximately 75% of adult patients remember precise circumstances leading to the acute onset of symptoms. Pang and Wilberger grouped these symptoms into three pathophysiological mechanisms.5 The first mechanism(50% of cases) consists of momentary stretching of a tethered conus medullaris, as would occur after prolonged sitting, forward bending, straight leg-raising exercise, or being placed in the lithotomy position during childbirth.5,11 The second mechanism (20% of precipitating events) consists of spinal canal narrowing from lumbar spondylosis and/or disk herniation with crowding of intraspinal contents in the presence of a TCS, and can be attributed to activities such as heavy lifting. The third mechanism involves trauma to the low back or buttocks as can occur with sudden forward and backward bending during a motor vehicle accident. There remains a 3- to 8-year delay between symptom onset and actual diagnosis.5,8,11,12

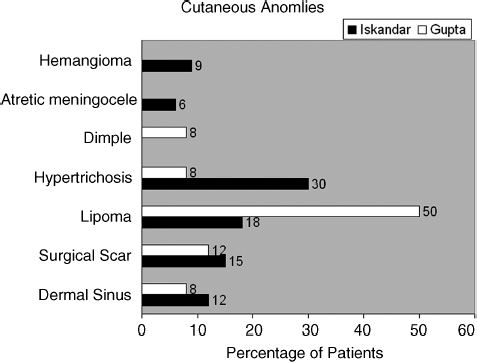

Approximately two thirds of SBO patients have cutaneous anomalies (Fig. 16.1 ).6,8,9 These cutaneous anomalies are often ignored or surgically removed for cosmetic reasons without concomitant attention to the spinal abnormality (these patients fit into group 2 of Pang’s classification scheme). Musculoskeletal deformities include lumbosacral lordosis; foot deformities such as high-arched feet and hammer toes; vertebral anomalies such as a bony septum or split vertebrae; and sacral agenesis. Mild scoliosis is present in up to 20% of patients,9 and the incidence of foot deformities ranges from 11 to 33%. 6,8,9 The spinal cord is tethered by a variety of spinal anomalies in 11 to 20% of patients with sacral agenesis or an imperforate anus; thus the classic recommendation is to obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on all patients with caudal regression syndrome of any severity.3,13,14

Fig. 16.1 Bar graph depicting the percentage of patients with cutaneous anomalies as reported in the Iskandar and Gupta series of adult patients with tethered cord syndrome.8,9 The term surgical scar is used to describe several patients who underwent previous surgery to correct cutaneous deformities.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Pain

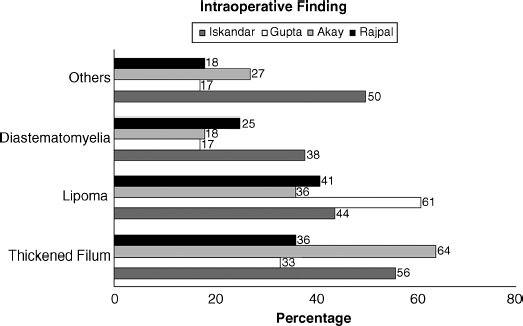

Low back and/or leg pain is the most common finding in adults with SBO-related TCS (Fig. 16.2).2,6–9 Pain occurs in a nondermatomal pattern with a shocklike sensation and burning quality. In a series of 61 adult patients by Rajpal15 et al, 34 (56%) and 30 (49%) patients presented with back and leg pain, respectively.2 Pain is usually exacerbated by physical activity, particularly involving flexion and extension of the lumbosacral area. Yamada12 et al described three postural changes that typically worsen pain in TCS patients. These were referred to as the “three B’s”: (1) the inability to sit with the legs crossed like Buddha, (2) difficulty with slight bending at the waist, and (3) holding a baby or light object (<2.3 kg) at waist level while standing. These maneuvers straighten the lordotic lumbosacral spine and presumably stretch the tethered spinal cord. Tethered cord pain thus often worsens with sitting, straining, and prolonged bed rest due to increased tension on the spinal cord caused by straightening of the lumbar curvature.

Sensorimotor Symptoms and Signs

Progressive leg weakness, paresthesias, and gait difficulty are common findings in SBO. Between 49 and 80% of adult patients with TCS present with motor or sensory signs or symptoms (Fig. 16.2).2,6–9 Motor deficits are usually asymmetric and include atrophy of the lower limbs, whereas sensory changes affect the lower lumbar and sacral regions and typically do not follow a specific dermatomal distribution.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree