The ageing population and the epidemiology of mental disorders among the elderly

Scott Henderson

Laura Fratiglioni

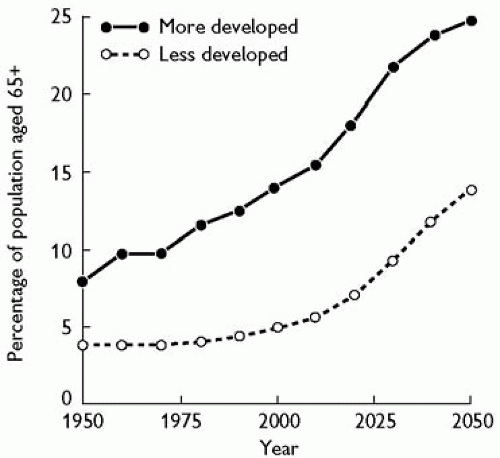

In the last decades the ageing of the populations has become a worldwide phenomenon.(1) In 1990, 26 nations had more than 2 million elderly citizens aged 65 years and older, and the projections indicate that an additional 34 countries will join the list by 2030. In 2000, the number of old persons (65+ years) in the world was estimated to be 420 million and it was projected to be nearly 1 billion by 2030, with the proportion of old persons increasing from 7 to 12 per cent.(2) The largest increase in absolute numbers of old persons will occur in developing countries; it almost triples from 249 million in 2000 to an estimated 690 million in 2030. The developing regions’ share of the worldwide ageing population will increase from 59 to 71 per cent. Developed countries, which have already seen a dramatic increase in people over 65 years of age, will experience a progressive ageing of the elderly population itself (see Fig. 8.3.1). The global trend in the phenomenon of population ageing has dramatic consequences for public health, health care financing, and delivery systems in the whole world. The absolute number of chronic diseases as well as psychiatric disorders is expected to increase. In this chapter, the epidemiological aspects of the most common psychiatric disorders of the elderly are summarized and discussed.

Depressive disorders

The epidemiology of depression in the elderly can be approached at three levels: its occurrence in the elderly living in the community, in those reaching primary care, and in the residents of hostels and nursing homes.

The community

It might be expected that, overall, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and disorders might increase in old age due to the loss of partners, friends, social status, retirement, income, and, above all, declining health. It is surprising, therefore, that surveys of the elderly in the general population have recurrently found rates that are significantly lower than in younger adults. Many of the large national surveys have not included persons aged over 65 years, but two exceptions are Australia, which found a 12-month prevalence of 1.7 per cent for the 65 years and over group compared with 5.8 per cent for all adults; and the New Zealand survey with rates of 2.0 and 8.0 per cent, respectively. It must be emphasized that these data refer to depressive symptoms in the elderly living in the community.

What is so far unproven is that such findings are indeed valid, and if they are, what might explain them.(3) They could be due to sample bias, in which elderly respondents with depressive symptoms may be more likely to decline to be interviewed than younger depressed people. Selective mortality has also been proposed, but cannot account for the size of the difference. It could be due to an error in case ascertainment, by which the interview instrument is not equally valid across age groups. For example, questions about depressive symptoms may be responded to differently by persons aged 20 and 80 years. Another possibility is a cohort effect in much of the Western world, where people born in the second half of the twentieth century have higher rates for depression.(4,5) This seems increasingly likely and may be due to a combination of social and environmental factors.

Primary care

Unsurprisingly, the prevalence of depressive symptoms is considerably higher in elderly persons consulting their doctor than in the general community. One study in London found a point prevalence of about 30 per cent. Where it has been possible to compare the rates for those cases recognized by their doctor with cases independently ascertained by a research measure, such as a screening instrument or standardized interview, a typical finding is that the general practitioner recognizes about two thirds of the mild cases, rising to some 90 per cent of the moderate to severe ones. Some cases are considered to be depressed when they are not. Another finding is that elderly persons with depressive symptoms may not mention them to their doctor, attributing them to their age and circumstances. These findings have led to programmes offering additional training for GPs and to recommending the use of brief screening tests in primary care. Because diagnosis would lead to appropriate treatment being given earlier in an episode of depressive disorder, its duration would be shortened. Since prevalence is the product of incidence and duration, the prevalence of depression would therefore be expected to fall. This is an example of the application of epidemiology to prevention, which is its ultimate service.

Depression in hostels and nursing homes

Prevalence rates are also higher in hostels and nursing homes. In the United States, levels as high as 30 to 50 per cent have been reported. It might be thought that the context of living in a nursing home would account for having depressive symptoms. But one study found that the excess over the general population rates was largely accounted for by medical disorders, environmental factors contributing little to the variance. This needs to be studied further because it seems counterintuitive that the social and physical environment, both of which can be modified, could be of little relevance.

What is important is that only about one quarter of cases are recognized. To compound the situation, those cases that are recognized tend to be treated with too low doses of antidepressants. Depressive symptoms are well known to occur comorbidly with cognitive decline and the dementias. These findings from clinical epidemiology have pointed to the need for better case recognition through education of medical and nursing staff, and to the use of routine screening of residents in such settings.

Suicide

For many decades across the world, the traditional pattern has been for the highest rates of suicide to be in elderly men. This has now changed. In over a third of countries, both developed and less developed, it is younger people who have come to carry the highest rates. The World Health Organization provides a valuable resource for such data, showing rates by age and gender for nearly all countries from 1950 onwards.(6) The pattern varies considerably between countries. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2002, men aged 75 and over had a rate of 10 per 100 000, whereas the highest rate was 18 per 100 000, in men aged 35-44 years. In the United States and in the Russian Federation, the rates for men aged 75 and over were 41 and 89 per 100 000, respectively.

The main risk factors for suicide in the elderly are a past history of an attempt, depressive disorder, physical illness or disability, chronic pain, recent losses, social isolation, and access to lethal means. While universal interventions are more powerful than selected factors in prevention,(7) these attributes can be used in selective intervention to identify groups at increased risk. Furthermore, being multiplicative, these markers are of great value in individual cases by alerting the clinician to a person needing particular attention. Here is another example of the use of epidemiology for prevention. A systematic review of suicide prevention strategies for all age groups concluded that two interventions did reduce rates: physician education in recognizing and treating depression; and restricting access to lethal means.(8) Both of these interventions have close relevance to the elderly.

Personality disorders

The subject matter here refers to older people who have enduring attitudes and behaviour that bring difficulties for themselves or for others.(9) There is only sparse information on the prevalence of personality disorders in the general population, let alone specifically in the elderly. One exception, based on a national survey of mental health, found a lifetime prevalence of 6.5 per cent across all age groups with a trend towards lower rates with increasing age.

In clinical practice, it has long been suggested that traits such as impulsivity and externalizing behaviours tend to become less frequent in later life, whereas anxiety-prone, dependent, schizoid, paranoid, or obsessional persons are likely to change little as they age, or to become more so. Bergmann’s pioneering enquiries among the elderly of Newcastle upon Tyne found that it was the anxiety-prone and insecure types that had late-onset neurotic disorders. A more recent study of late-life depression found an overall prevalence of comorbid personality disorder of 10-30 per cent. The group formerly known as neurotic and more recently as Cluster C in the DSM classification, had the higher prevalence. The Cluster B group, those with borderline, narcissistic, histrionic, and antisocial traits, were rare. What is not yet established, however, is if this lower prevalence also exists in the general population of the elderly, not just among cases with depressive disorder who have reached treatment in specialist services.

The epidemiology of personality disorders in later life is therefore significant for two reasons. First, some types are associated with increased risk of anxiety, depression, or paranoid states (vide infra). Second, there remains much yet to understand about the natural history of the personality disorders across the lifespan.

Psychosis of late onset

For the functional psychoses of late life, epidemiological information comes from two sources: studies of persons who have reached psychiatric services; and surveys of elderly persons living in the general community.(10) Psychotic symptoms probably exist as a continuum of severity, with only the more developed cases meeting diagnostic criteria. These often, but not always, reach psychiatric services, not uncommonly through being brought to the attention of the police. States phenomenologically similar to those found in clinics do occur in the community in non-trivial numbers. For cases that reach the threshold for a diagnosis by virtue of the range and severity of symptoms and behaviour, it has been proposed that cases with onset after the age of 60 years be called ‘very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis’. The syndrome has a 1-year prevalence

of 0.1 to 0.5 per cent. For advancing knowledge about the aetiology of schizophrenia, any information on it might be useful in explaining why people with this syndrome have reached the seventh decade or later in life without becoming psychotic, and only then develop it. It is more common in women. This is unlikely to be due to different social visibility or access to services. It is associated with a better premorbid level of social and occupational functioning. Premorbid paranoid or schizoid traits have been implicated and both clinical and community-based studies have found an association with sensory impairment such as deafness or poor eyesight. Personal and environmental factors associated with ageing have been considered, such as physical ill health, bereavement, loss of friends, and loss of income, but these have not been shown to contribute significantly. Genetic factors appear to be less important than in earlier onset schizophrenia.

of 0.1 to 0.5 per cent. For advancing knowledge about the aetiology of schizophrenia, any information on it might be useful in explaining why people with this syndrome have reached the seventh decade or later in life without becoming psychotic, and only then develop it. It is more common in women. This is unlikely to be due to different social visibility or access to services. It is associated with a better premorbid level of social and occupational functioning. Premorbid paranoid or schizoid traits have been implicated and both clinical and community-based studies have found an association with sensory impairment such as deafness or poor eyesight. Personal and environmental factors associated with ageing have been considered, such as physical ill health, bereavement, loss of friends, and loss of income, but these have not been shown to contribute significantly. Genetic factors appear to be less important than in earlier onset schizophrenia.

Alcohol and drug dependence

It is generally believed that the prevalence of alcohol abuse and dependence declines during adult life and that the elderly have low rates in most communities. This may well be the case, but some other factors have to be considered. Whatever the prevalence, the absolute numbers will rise in the future because of the unprecedented growth in the elderly population. Next, the assumption may be false. In community surveys, errors in the ascertainment of alcohol abuse may lead to an underestimate for older persons. Most screening instruments were developed for use on younger adults, so their validity in the elderly is largely undetermined. Measures of the quantity drunk may mislead because smaller amounts may have an intoxicating effect in persons whose body fat, lean tissue, cerebral reserve, and metabolic function have declined. So the usual cut-off for problem drinking may be set too high for the elderly. One review of screening instruments concluded that the CAGE and MAST-G scales were appropriate, whereas other widely used instruments were not.(11) Next, all the studies have been cross-sectional. The elderly may have lower rates because of a cohort effect, whereby people born in the first half of the twentieth century may have been more moderate drinkers for all their life, compared to the high levels of consumption that are now found in the young of both sexes.

The actual values for prevalence are dependent on the instrument used and the definition used to define problem drinking, alcohol abuse, or dependence.(12) One review of community studies gives a figure of 5.1 per cent using various definitions. Invariably, men have higher rates than women. There is also considerable variation between countries and across different cultures. In identifying cases, a distinction of clinical significance needs to be made between late-onset and long-standing alcohol abuse. In primary care, accident and emergency departments, hospital in-patients, and nursing homes, the prevalence is much higher, yet cases are consistently under-recognized. The use of screening instruments in all of these settings has been advocated to improve this.

Alcohol abuse carries important comorbidity. In addition to all the established medical complications, it is associated with falls, subclinical delirium, cognitive decline, and depression. One study demonstrated a five-fold increase in the risk of developing a psychiatric disorder, especially depression and dementia. Simultaneous use of benzodiazepines, itself common in older persons, is clearly an additional and important factor. Against all this, it should be recalled that moderate alcohol use has been found in population studies to be associated with better mental and cardiovascular health, as well as being subjectively enjoyable.

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

In the last two decades the dementia field has registered a tremendous scientific progression in many research areas including aetiology, pathogenesis, clinical aspects, treatment, and prevention. These advances have opened new perspectives, especially concerning definitions and diagnostic criteria, which have a relevant impact on epidemiological research.

Dementia is still defined as a syndrome which includes memory deficits and disturbance of other higher cortical functions; these major symptoms are commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour or motivation. However, it has become apparent that memory impairment may not necessarily be the major or first symptom for dementia subtypes such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and vascular dementia (VaD). Furthermore, as the current definition requires impairment severe enough to interfere with daily functioning, in several cases a delay of the diagnosis occurs. For that reason, a new research line has emerged with the aim to detect early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias, and the terms mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and cognitive impairment no-dementia (CIND) have been proposed to identify those subjects that show a clear cognitive deficit but do not fulfil diagnostic criteria for dementia. Finally, it is well known that dementia syndrome can be induced by many different underlying diseases, and that a differential diagnosis may be difficult for several reasons. AD as well as other dementia subtypes shows heterogeneity with distinct clinical and pathological characteristics; many different dementing disorders overlap in clinical and pathologic features; and different dementing disorders may make a common contribution or interact in causing dementia symptoms. Thus, rather than viewing, for example, AD and VaD as dichotomous entities, it may be more relevant to consider the role of their additive or synergistic interactions in producing a dementia syndrome.(13,14)

Following these new perspectives, in this chapter we will summarize the major findings from the most recent epidemiological research according to three major topics: early detection of AD and other dementias, incidence and risk factors for AD and dementia, and prevalence and impact of the dementing disorders at the individual and societal levels.

Early detection

As diagnostic criteria for AD require gradual onset of cognitive deficits, it is expected that cognitive disturbances are present already before the diagnosis can be rendered. Cognitive deficits are observable up to 10 years before dementia diagnosis with a sharp decline more evident in the final 3 years,(15) and occurring in episodic memory as well as in other cognitive domains such as executive functioning, verbal ability, visuospatial skills, attention, and perceptual speed.(16) However, our capability to use such early disturbances as a predictive tool of incipient dementia is strongly limited by several concomitant facts: (1) cognitive decline is also present as a function of the normal ageing process; (2) several conditions other than AD may lead to cognitive disturbances in the elderly; and (3) dementia-free patients with cognitive impairment observed in specialized clinical settings are different from cognitively impaired persons detected in the general population.(17)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree