CHAPTER 22 The Cerebral Venous System in Meningioma Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Venous sacrifice has always been a key problem in neurosurgery. For many years, surgery in and around the superior longitudinal and lateral sinuses has been debated in the literature.1–6 Neurosurgeons understand the importance of Labbé, Trolard, and sylvian veins; they have learned to preserve the parasagittal bridging veins and have discovered the venous anastomotic channels, mainly with the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). But in meningioma surgery, interest has focused more on arterial vascularization, arterial feeders, and preoperative embolization than on preoperative study of veins. However, most postoperative pitfalls in meningioma surgery, primarily in convexity and parasagittal meningiomas, have a venous origin, due to either a venous infarct or sacrifice of an anastomotic channel. Therefore, for some time we have directed much attention in preoperative angiography, MRI, and MRA toward the study of veins close to the meningioma or en route to it in a falcine location. We have also tested ourselves on the venous pathways and channels when a sinus was occluded without related neurologic signs.7 In this chapter, we consider convexity, parasagittal, and falcine meningiomas from the aspect of venous challenge.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

The gold-standard treatment is complete removal of the tumor as well as the invaded dura and bone.8 But total removal should never be attempted without preservation of quality of life. Therefore, it is crucial to keep several principles in mind so as to plan the surgical opening adequately and to place the head of the patient in the best position to benefit from brain relaxation as described in the text that follows. At present, although we may rely on neuronavigation systems to avoid a wrong opening, it is also mandatory to enter in the computer program information on all the veins to preserve.

CONVEXITY MENINGIOMAS

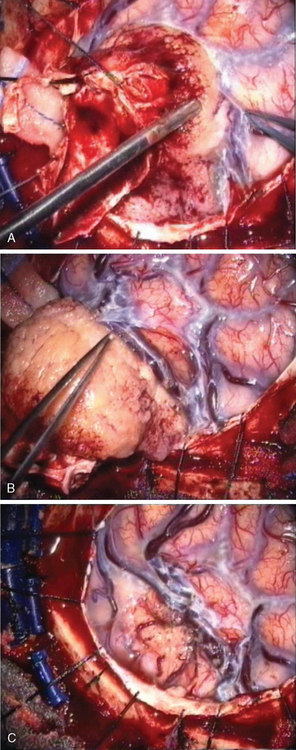

Convexity meningiomas rarely impair venous drainage but the second challenge is the dissection of the veins adhering to the tumor. The key is to stay extrapially as much as possible and to dissect the tumor in the arachnoidal plane. Many arachnoidal adhesions may be cut without coagulation (Fig. 22-1). Even bipolar coagulation is dangerous if it is too close to a vein. Meticulous dissection, never hurried, will successfully separate veins that initially seemed impossible to spare. It will keep the cortex intact in extrapial meningiomas but also preserve the integrity of the surrounding cortex in subpial tumors. Traction is applied to the tumor to lift it after progressive separation from the brain. This helps to cut arachnoid adhesions and coagulate away progressively arteries as small branches feeding the tumor, as well as veins that are more fragile and more delicate to dissect. The technique is recommended in all convexity locations, not only in the rolandic area, as brain softening from venous infarct may lead to disastrous consequences.

PARASAGITTAL MENINGIOMAS

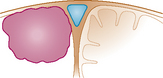

Parasagittal meningiomas are tumors arising at the convexity of the hemisphere, just off the midline adjacent to SSS and falx, which may involve one, two, or three walls of the SSS with or without occlusion of its lumen. They have a predilection to arise where arachnoidal granulation tissue is the most pronounced9 and in 15% they invade the SSS.8 Simpson8 studied the possibilities of recurrence of intracranial meningiomas and reported that the infiltration of the SSS was a major reason for tumor recurrence. It is well established that the recurrence rate correlates significantly with the quality of the resection but is somewhat tempered by the knowledge that small tumor remnants may at times remain unchanged for several years. The goal is complete removal of the tumor, but the quality of life may be compromised by the surgery. Consequently, complete removal of parasagittal meningiomas by resection of the dural attachment involving the wall(s) of the SSS, and their reconstruction, represents a real surgical challenge. In the 1970s, several neurosurgeons described their surgical techniques for reconstruction of the SSS and collateral veins in dogs4,10 or in patients with good clinical and radiologic results.1,3 At the time, only computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography were available. For the most part, classification of meningiomas was essentially based on surgical findings.

CLASSIFICATION, DIAGNOSIS, AND PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

In 1978, we described a surgical classification with 8 subtypes of parasagittal meningiomas1 but as a result of our experience during the last 20 years, we have simplified it into 5 categories (Table 22-1) that are more in accordance with our current surgical policy.11 This classification is designed to help plan a rational surgical strategy.

TABLE 22-1 Classification of parasagittal meningiomas

| Type I: | The meningioma is attached only to the outer surface of the sinus |

| Type II: | The meningioma enters the lateral recess of the SSS. |

| Type III: | The meningioma invades one SSS wall. |

| Type IV: | The meningioma invades two walls of a still patent sinus |

| Type V: | The meningioma spreads over the midline, invades the three walls with occlusion of the SSS. |

Reproduced with permission from Hancq S, Balériaux D, Brotchi J. Surgical treatment of parasagittal meningiomas. Semin Neurosurg 2003;14(3):203–10.

CT provides a means to see bone invasion by the meningioma, but currently MRI with and without gadolinium is the most accurate radiologic exam to determine the configuration, size, and consistency of the tumor, and the relationship among the meningioma, the adjacent brain, and the blood vessels. But the gold-standard examination today is MRI combined with MRA, as we reported in 1996.7 MRA provides all the crucial information concerning the venous system without the invasiveness of the DSA: the degree of SSS invasion, the permeability or the thrombosis of the SSS, and the major pathways of collateral circulation on both sides. MRA is even superior to DSA because MRA detects blood flow in all directions simultaneously:

OPERATIVE APPROACH

Position

The patient is placed in a supine, lateral, or prone position according to the location of the meningioma (anterior third, middle third, or posterior third of the SSS). In the anterior third, the patient is supine with the head slightly elevated. In middle third prerolandic area, the patient is placed in a lateral position with the head well elevated so that the scalp over the center of the tumor is uppermost,12 but in front of the rolando–parietal area, we prefer to put the patient in a lateral position with the tumor down, similar to the position used in the posterior third. In the posterior third, we prefer to place the patient in an adapted three-quarter prone position with the tumor below the midline. The position, which we commonly use for pineal area tumors, takes advantage of gravity by allowing the brain to fall away from the midline, which avoids unnecessary brain retraction.13,14 This is of special interest when the connection with the falx is significant, or when the attachment to the dural convexity is small.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree