Several baseline characteristics have also been associated with risk of regain. Of particular interest is the fact that those who have achieved their successful weight loss most recently have the greatest risk of regain. After 3–5 years of maintenance, the risk of regain appears to be lowered (36). Individuals whose weight loss was initially triggered by a medical event also have a lower risk of regain (40).

Perhaps the finding of greatest concern is that individuals who regain weight are unlikely to subsequently recover. The smaller the weight gain, the better the chance of recovery; however, only 20% of participants totally recover from even a 1–3% weight gain (37). These data attest to the need to prevent any weight regain from occurring.

In summary, based on findings from the National Weight Control Registry, it appears that behaviors associated with successful weight loss maintenance include eating a low-calorie, moderately low-fat diet, eating breakfast, regular self-monitoring, and engaging in high levels of physical activity. People who maintain these behaviors are more likely to avoid weight regain than people who do not. Thus, the ability to maintain behavioral changes is critical for successful weight loss maintenance.

Research Testing Strategies for Weight Loss Maintenance

A second approach to understanding how to improve weight loss maintenance is to test, in randomized, controlled trials, specific strategies that may promote weight loss maintenance. Participants are frequently recruited for these trials after they have lost weight and then are assigned to specific maintenance strategies. Alternatively, all groups may receive the same initial program and then be randomly assigned to different maintenance programs. A variety of strategies have been tested for their effects on maintenance of weight loss. Some of the more effective strategies are described below.

Extended Contact

A variety of studies have shown that continued contact with participants helps promote weight loss maintenance (7). The longer patients remain in treatment, the longer they maintain the prescribed behavior changes, and consequently the longer they maintain their weight loss. As evidence of this, Perri and colleagues (41) compared a 20-week program with a 40-week program and found that the latter improved adherence to treatment recommendations and increased weight loss by 35%. Likewise, following a standard six-month behavioral program, those participants who continued to be seen biweekly maintained their weight losses better than those who received no further contact (7).

Given the cost of these face-to-face contacts, in terms of both labor and time, it is interesting to consider the use of telephone contacts. Wing and colleagues (42) had research staff call participants weekly for 12 months to inquire about adherence to self-monitoring and body weight. The hypothesis was that these calls would serve as a prompt to participants to continue to adhere to these aspects of the protocol. Although the number of calls completed and reported record-keeping over the follow-up period were inversely associated with weight regain, the group receiving the calls did not experience significantly less weight regain than the no-contact control group. In contrast, telephone calls made by the client’s therapists, which included counseling and advice, did improve maintenance (43). Such calls, however, may be just as expensive (or more expensive) than seeing participants in face-to-face meetings.

Relapse Prevention and Problem-Solving Skills

Marlatt and Gordon (44) have suggested that an important aspect of behavior change programs is to teach participants how to deal with lapses to keep them from becoming relapses. They argue that lapses are inevitable, and that it is the reaction to these lapses (rather than the lapse per se) that leads to relapse. Following the suggestions of Marlatt and Gordon, many programs now include “relapse prevention training” which includes both learning to anticipate and avoid lapses, and learning how to deal with lapses, if they occur.

Two studies have tested relapse prevention training as part of maintenance intervention. Perri and colleagues (43) found that using relapse prevention training as one component of a multi-component program, which also included ongoing therapist contact, was effective in improving maintenance of weight loss. They speculated that teaching relapse prevention during the maintenance phase, and using the telephone contacts to help participants actually learn to apply these strategies when they experienced lapses, may have made this an effective combination. This combination of relapse prevention training and post-treatment contact was also shown to be effective by Baum, Clark, and Sandler (45).

However, Perri and colleagues (46) found that teaching participants the skills related to relapse prevention was not as effective as a problem-solving approach. Participants in this trial received a standard five-month behavioral program and then either 1) no further contact; 2) bi-weekly meetings with training in relapse prevention; or 3) bi-weekly meetings with problem-solving. In the problem-solving group, the therapist led the group in applying a problem-solving approach to a specific problem identified by one of the group members. Weight losses from baseline to month 17 averaged 10.8 kg in the problem-solving condition, 5.8 kg in the relapse prevention condition, and 4.1 kg in those given no further contact. The problem-solving intervention significantly improved maintenance of weight loss while the relapse prevention program did not. In interpreting these findings, Perri suggests that the relapse prevention program was a more didactic program and may not have allowed as much opportunity for individualization. In contrast, in the problem-solving condition, participants spent each session dealing with a problem that a group member recently encountered. Thus, this study suggests that the mode of delivery as well as the content of the intervention may influence the outcome.

Increased Physical Activity

As described above, there are several studies, including the National Weight Control Registry, which indicate that successful weight loss maintainers engage in very high levels of physical activity. Consequently Jeffery and colleagues (47) hypothesized that the levels of physical activity that are typically prescribed in a weight-loss program (1,000 kcal per week) may not be sufficient for long-term weight control. These investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing the 1,000 kcal/week recommendation with a prescription of 2,500 kcal/week. A total of 202 overweight men and women participated in this study; all received the same reduced-calorie diet and training in behavior modification skills, but half were assigned to the 1,000 kcal/week exercise goal and the others to the higher goal. To help the high physical activity group achieve this goal, they were encouraged to identify 1–3 exercise partners to exercise with them and received counseling from an exercise coach and small monetary incentives.

This study showed that participants in the high physical activity group reported exercise expenditures of about 2,300 kcal/week, thus almost reaching the activity recommendation and representing significantly higher levels than the standard group (which achieved approximately 1,800 kcal/week). The high exercise group also achieved significantly greater weight loss at 12 months (8.5 vs. 6.1 kg) and 18 months (6.7 vs. 4.1 kg).

In a follow-up study (48), these authors reported that the differences in exercise levels were not maintained at 30 months. Both groups decreased their physical activity and experienced weight gain. However, those participants who were able to continue expending >2,500 kcal/week in physical activity maintained a weight loss of 12 kg at 30 months vs. 0.8 kg in those who exercised less. These data highlight the importance of maintaining high levels of physical activity to promote long-term weight loss and maintenance.

Social Support

The only study to specifically evaluate peer support as a maintenance strategy was conducted by Perri and colleagues (49). After completion of a standard behavioral program, participants in the peer support condition were taught to run their own peer support meetings. Space was provided and meetings were held biweekly for seven months. This intervention did not significantly improve maintenance compared to a no-contact control.

In contrast, Wing and Jeffery (50) found partial support for a peer-based manipulation. In this study participants were allowed to choose whether to enter a program by themselves or with three friends or family members. Thus, this part of the study was not randomized. However, within each of these groups, half of the subjects were randomized to receive a social support intervention, which included inter-group competitions and intra-group cohesiveness activities, and half did not receive this intervention. Both recruitment strategy and social support manipulation affected the maintenance of weight loss from the end of the four-month program to a follow-up at month 10. Only 24% of participants who were recruited alone and received a standard behavioral program without the social support manipulation maintained their weight loss in full. In contrast, 66% of those who were recruited with friends and received the social support intervention maintained their weight loss in full.

Multi-Component Approaches

In almost all of the trials described above, even the most successful group experiences some weight regain over the 12-month follow-up interval. One of the few examples of a program that led to no weight regain was a multi-component program tested by Perri and colleagues (51). Participants who were assigned to receive post-treatment contact (biweekly group sessions over the full year), plus social influence (monetary group incentives, active participant involvement, and training in peer support strategies), plus aerobic exercise (with exercise goals gradually increasing to 180 minutes/week) maintained 99% of their initial weight loss at the 18-month follow-up. Although this group appeared most effective, the only statistically significant effect was that all four groups that received ongoing therapist contact had better maintenance of weight loss than the group receiving no ongoing contact. This finding highlights the importance of ongoing contact for the maintenance of weight loss, but suggests that adding a variety of other strategies may be useful in maintaining weight loss long term.

Teaching the Skills of NWCR Members to Recent Weight Losers

Wing and colleagues have recently reported results of a randomized clinical trial of weight loss maintenance (52). This study is unique in the literature because it recruited individuals who had lost at least 10% of their body weight within the past two years regardless of how they had lost their weight. These individuals then participated in an 18-month study designed to prevent weight regain.

The 314 participants in this trial were 52 years of age on average and 81% were female. They had recently lost an average of 19 kg; after this successful weight loss, these participants had a BMI of 28.6 and weighed 77.8 kg on average. The 314 participants were randomly assigned to the control group, which was sent quarterly newsletters, or to receive an active intervention via the Internet or face-to-face meetings. The intervention was based on self-regulation and taught participants to weigh themselves regularly and use the information from the scale to determine if and when adjustments in diet and physical activity were needed. Participants in the intervention attended four weekly meetings and then monthly meetings (via face-to-face group meetings or Internet chat rooms) and were taught to model their behaviors on those seen in NWCR members, including high levels of physical activity, low-calorie, low-fat diets, and high levels of vigilance. To increase vigilance, intervention group members were instructed to report their weight (via phone or email) on a weekly basis. If their weights were within 1.4 kg of starting weight (green zone; “go”), they were encouraged to reinforce themselves and sent small green gifts (green tea; green gum) to recognize their success; weight gains of 1.4–2.2 kg were considered the yellow zone (“caution”) and problem-solving was encouraged. The red zone (“stop”) occurred at weight gains of 2.3 kg or more. At this time, participants were encouraged to get back to active weight loss strategies and were offered additional counseling.

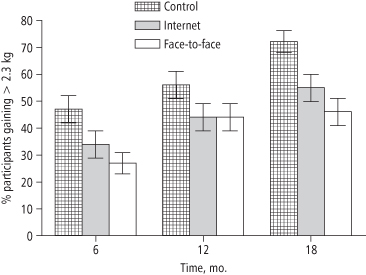

This study found that the face-to-face intervention significantly decreased the average weight regain compared to control (+2.5 kg vs. +4.9 kg, respectively), but the Internet program did not differ from either of the others (+4.7 kg). The intervention offered via face-to-face groups or via the Internet significantly reduced the percentage of participants who regained 2.5 kg or more over the 18-month program. After 18 months 72% of the control group had regained 2.5 kg or more, compared to 45.7% in the face-to-face group and 54.8% in the Internet group (Figure 22-2). This self-regulation model thus shows promise in helping to prevent weight regain in successful weight losers.

Figure 22-2 Proportion of Participants Who Regained 2.5 kg or More at 6, 12, or 18 months

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree