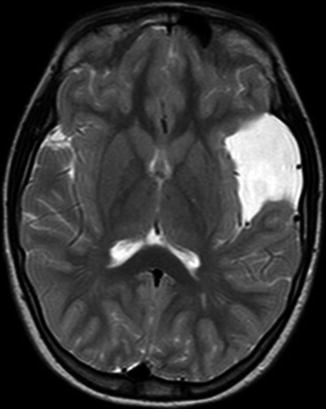

Fig. 15.1

Axial T2w MRI of left medium-size Sylvian cyst inducing a shift of midline cerebral structures with compression and distortion of the ipsilateral ventricle. CSF spaces of the convexity are reduced on the left side compared to the contralateral side. The volume of the left hemicranium is slightly bigger than the right one. The association of the abovementioned signs suggests a mass effect of the lesion

Among the clinical manifestations of Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts, three are considered to be particularly relevant for the surgical indication: headache, epilepsy, and psychomotor retardation.

Actually, about 70 % of “symptomatic” subjects complain of headache, which is often of a chronic type. Unfortunately the characteristics of this symptom are nearly always nonspecific and not easily attributable to the presence of the cyst. The headache, in fact, does not appear to correlate with the size of the cyst or to phenomena of compression/distortion over the neighboring vascular or meningeal structures. However, if not interpreted differently, headache may be considered at least for justification of further diagnostic work-up and even invasive intracranial pressure recordings [23].

Prolonged ICP recordings may actually reveal an abnormally high mean CSF pressure or point out the occurrence of abnormally high pressure waves during physiological sleep as well as arterial pulses of excessively large amplitude. On this ground, the results of a study we carried out on a series of pediatric patients with temporal cysts who underwent prolonged ICP recordings demonstrated that Galassi type I cysts were almost always associated with a normal ICP, whereas abnormally high ICP pressure values were found in all the Galassi type III cysts [4]. Both normal and abnormally high intracranial pressures could be detected in children with Galassi type II cysts, so making impossible to predict the values of intracranial pressure on the basis of neuroradiological investigations in this specific subgroup of patients, that is, in a significant percentage of cases.

Epilepsy is a common cause for performing neuroradiological exams; consequently it is possible that in some subjects these investigations may reveal the presence of temporal arachnoid cysts. However, a strict correlation of seizure disorder with the presence of the lesion is still lacking in the literature. First of all, in the majority of cases, there is no direct concordance of the seizures semeiology and the location of the cyst. Furthermore, in many children the electrophysiological exams often reveal contralateral anomalies, suggesting a high probability of associated diffuse developmental cortical anomalies involving also the opposite hemisphere. Finally, the surgical excision of the cyst or its marsupialization is not necessarily followed by seizure disappearance or reduction, even when the volume of the cyst is significantly reduced postoperatively.

Mental retardation and behavior problems are also described frequently in association with Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts. With regard to epilepsy, the relationships between the cognitive and behavioral anomalies and the presence of the cyst are far to be demonstrated. In the same way, the benefit of surgical treatment over these symptoms is yet to be confirmed. Only a single group of scientists reported an improvement of the cognitive disorders on a series of adult patients [24]. In children, the majority of authors experienced different results: indeed, no significant psychomotor improvement has been reported regardless of the surgical modality and, above all, the entity of cysts size reduction in more recent series [1, 20, 23]. In fact, a primary developmental hypoplasia of the temporal lobe rather than an atrophy or compression exerted by the lesion may be taken into account for the interpretation of the clinical manifestations. In favor of such a hypothesis is also the common observation of absent neuropsychological impairment even in children with large cysts and those located into the dominant hemisphere.

Large percentages of patients having arachnoid cysts in the middle cranial fossa identified by radiological means develop no symptoms at all (Fig. 15.2) [21]. Indeed, as was pointed out from an international survey [23], most pediatric neurosurgeons (more than 60 %) would adopt a “wait and see” policy in cases of incidental diagnosis or at least would suggest further diagnostic examinations, such as functional MRI, cine-MRI, SPECT, PET neuropsychological evaluations, and EEG to confirm the pathological role of the lesion.

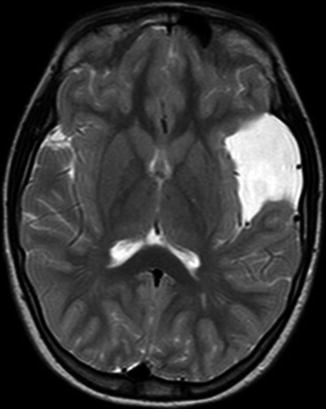

Fig. 15.2

Axial T2w MRI of left medium-size Sylvian cyst showing no mass effect on the adjacent cerebral parenchyma. This patient was followed for 4 years after diagnosis, and neither symptoms nor signs which could be referred to the lesion were exhibited by the patient during that period

No doubts concerning surgical indication arise when symptoms or signs due to increased intracranial pressure are detected, namely, focal neurological deficit or decreased consciousness, often related to a hemorrhagic complication; however these are, actually, rare events. However, in the absence of specific symptoms related to a localized or diffused increasing intracranial pressure, several authors advocate the use of a “prophylactic” operation in order to prevent the risk of intracranial bleeding due to spontaneous or traumatic tearing of the cyst linings and their fragile vessels, resulting in intracranial hemorrhage and subdural fluid accumulation. The actual incidence of spontaneous rupture of middle cranial fossa arachnoid cysts is still unknown: Bilginer et al. found a 2.27 % incidence of subdural hematoma requiring surgical therapy over a series of 132 pediatric patients [3]. In a retrospective review of 343 patients affected by Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts, Sprung et al. found a series of 60 cases (17.4 %) admitted for subdural and/or intracystic effusions, among whom 54 (15.7 % of the entire series of 343 patients) required surgical intervention [21]; they found also that most of the cysts (41/60) fulfilled the criteria for type II cysts, that subdural effusions were mostly ipsilateral located and occurred after traumatic events, and that almost half of the patients were younger than 19 years of age. This occurrence rate of subdural collections is significantly higher than those reported by other authors [25] and was interpreted as due to the large number of cases who were referred to the center as well as to the common availability of a CT scan examination.

Overall, according to the available data from the literature, the incidence of subdural fluid collections in the set of untreated temporal arachnoid cysts may be estimated from about 2–17.4 % of cases, which does not differ significantly from the occurrence rate described in most series after surgical operation, challenging so far the prophylactic value of the surgical treatment of temporal arachnoid cysts for such type of risk [5]. In particular, in the series by Spacca et al., four patients suffered a head injury 3–60 months after successful surgery resulting in hemorrhagic complications [20]. Moreover, spontaneous disappearance of even large middle cranial fossa cysts has been described [2, 18, 26].

15.3 The Choice of Surgical Technique

The main goals of the surgical treatment of Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts are the elimination of the mass effect of the lesion and the prevention of its recurrence in order to improve or normalize the CSF dynamics. These goals can be pursued with a variety of surgical procedures: extra-thecal shunts from the cyst to the peritoneal cavity, shunting of the cyst content into the ventricular system, microsurgical opening (marsupialization) of the cyst linings into the adjacent arachnoid spaces and cisterns, cyst lining excision, and endoscopic opening of the cyst into the basal cisterns.

According to a recent international survey among pediatric neurosurgeons [23], craniotomy and cyst wall marsupialization/removal was considered the primary surgical treatment in 66 % of the obtained responses; 28.8 % of the neurosurgeons interviewed would prefer an endoscopic approach (pure 15.5 % and assisted 13.3 %, respectively). Only 6.6 % would consider, nowadays, cysto-peritoneal shunt as the first-line treatment in Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts.

In recent years, the cysto-peritoneal shunt, once regarded the most simple and effective procedure to treat Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts, has been progressively abandoned because of the known complications of shunt surgery (shunt malfunction, occlusion, infection) [1, 11, 19] and, in particular, the late development of shunt dependency and acquired Chiari type I malformation, even though the procedure is associated with the higher evidence of objective results, that is, the cerebral parenchyma re-expansion.

Consequently, cyst lining excision and cyst membrane marsupialization have become the most utilized techniques worldwide. Unfortunately, the degree of cerebral parenchymal re-expansion associated with these types of surgical procedure as shown by computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not so obvious as in cases managed by cysto-peritoneal shunt. As a result, the “success” of the surgical treatment is more difficult to establish when using these techniques.

Paradoxically, the comparative analysis of series focusing on the surgical outcomes may only define the percentage of “failure,” that is, a cyst whose size remains unchanged after the surgical treatment with certainty. On the other hand, successes are considerably more difficult to be assessed in the large majority of patients, that is, in cases where the cyst decreases in size only partially.

Indeed, some authors simply report “satisfactory” reduction of the cyst without referring to the relative decrease in size of the lesion or to absolute numeric values defining the entity of the surgical “success.” Others group into the category of good outcome all the cases in which the size of the lesion appears to be diminished after the operation using, however, adjectives such as “minimal,” “partial,” “moderate,” and “incomplete” which obviously do not allow a reliable evaluation or comparative analysis. Actually, the “complete” resolution of the cyst is rarely reported. Furthermore, only exceptionally the postoperative modifications of the cyst volume, which define the surgical outcome, have been associated with the effects of the treatment on the clinical manifestations. It is evident how, in the absence of objective evaluation criteria, the definition of outcomes might be biased by the subjective judgment of the neurosurgeon. The neuroradiologist could contribute to alleviate such a limitation not only by measuring the degree of the cyst reduction objectively but by furnishing also additional data with regard to the cerebrovascular compression, stretching, and distortion. Unfortunately, even though the introduction of progressively more effective neuroimaging tools to calculate the volume of the cyst might provide more sound figures in the future, until now no objective measurements are available to relate the “success” of the surgical treatment based on the variations of specific pre- and postoperative parameters.

Historically, the principal debate over temporal arachnoid cysts management has focused on the comparison of microsurgical techniques and shunt implantation [1, 8, 14, 16, 19, 28], endoscopic procedure being applied increasingly on temporal arachnoid cysts cases “only” in the last 10 years [6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15, 20].

The implantation of a cysto-peritoneal shunt has been considered for long time the less invasive surgical procedure to treat temporal arachnoid cysts in terms of perioperative morbidity with a higher success rate of significant decrease in size or complete obliteration of the cyst [19]. Cysto-peritoneal shunts, however, are weighted by the constant risk of shunt infections/malfunctions, occlusions, as well as shunt dependency [1, 11, 19]. Later on, the occurrence of hindbrain caudal and upward herniation may be observed due to a progressive craniocerebral disproportion, especially in subjects operated on in early age [5]. Differently from a ventriculoperitoneal CSF shunt, the cysto-peritoneal shunt should, at least theoretically, drain from a close cavity, consequently making difficult to understand why the induced change in size of the lesion may differ in the various patients, without considering a coexisting primary hypoplasia of the temporal lobe. Some attempts have been made to investigate the action of this type of shunt. Arai et al. in a series of 77 subjects with temporal arachnoid cyst who had undergone the implantation of a cysto-peritoneal shunt device monitored the intracystic pulse wave by puncturing the shunt system [1]. They found that the intracystic pressure and the amplitude of the intracystic pulse wave increased when the shunt was closed to subsequently decrease when it was open. The authors concluded that the action of the shunt in decreasing the cyst volume was not limited to the fluid subtraction but also at diminishing a possible pathogenetic factor for cyst enlargement, namely, the intracystic pressure pulsations. They also proposed the removal of the outer membrane of the cysts wall to avoid shunt malfunction, considering that the outer membrane detaches easily from the dura mater after the shunt procedure, causing plugging of the shunt tube.

On the other hand, open craniotomy and cyst fenestration with or without cyst wall removal are considered an aggressive approach, being weighted by major complications, namely, subdural hematomas or hygromas, oculomotor palsy, meningitis, hemiparesis, seizures, and even death [22]; however, this type of procedures allows marsupialization of the cyst under direct microscopic vision, avoiding stripping of the arachnoid membrane so reducing the risk of bleeding [9]. Actually, in recent reports, perioperative mortality and morbidity are similar in comparison with shunting procedures [23]. According to some authors [19], the complete removal of the cyst wall is neither possible nor necessary to obtain an effective decompression of the cyst. However, despite anecdotal reports suggesting that a limited partial excision of the cyst wall might be an effective and sufficient treatment, fenestration of the cyst into the basilar cisterns has widely proved to offer a greater chance of successfully dealing with the condition and restoring normal CSF dynamics, resulting in the elimination of the need of a shunt in many cases [16].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree