The Consultation and Liaison Processes to Pediatrics

Jonathan M. Campbell

Laurie Cardona

Children with medical disorders present with psychiatric and psychosocial concerns, frequently at rates that are much higher than expected when compared to the general population. For example, psychological disorders have been documented at rates 2–4 times higher in populations of children with chronic medical illness when compared to estimates within the general population (1). Although children with medical illness appear to be at greater risk for psychopathology, the presence of symptoms appears to vary somewhat according to medical illness (2). In addition to psychosocial needs expressed by children with medical illness, family members may also present with coping and adjustment difficulties resulting in requests for consultation. Parents of child survivors of cancer, for example, report posttraumatic stress symptoms associated with the distress of a life-threatening illness and its treatment, with roughly 14% of mothers and 10% of fathers meeting formal diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (3). The fairly common occurrence of child and family psychosocial needs within pediatric populations has resulted in the professional specialties of consultation-liaison (C/L) child psychiatry and pediatric psychology. Although consultation requests for C/L services may come from outpatient settings and the emergency department, the present chapter is focused on the consultation processes of C/L services to inpatient pediatric departments, arguably the most frequently used mechanism for C/L services.

Differences in Theoretical Orientation, Training, and Culture between Child Psychiatry/Psychology and Pediatrics

Prior to introducing models of consultation and describing the “nuts and bolts” of C/L consultation, it is useful to delineate and describe differences between pediatric and psychiatric/psychological orientations, training, and treatment cultures, which have been identified as challenges to effective C/L work (4). Despite each specialty area being concerned with child-based healthcare, there is surprisingly limited shared training experience for child psychiatry and pediatrics. The overlap is even less for training within pediatric psychology, which results in less appreciation for service provision within medical settings, such as care that occurs within inpatient hospital wards. Another important difference between pediatrics and child psychology/psychiatry is the conceptualization of a child’s functioning and adjustment from a primarily biomedical as opposed to a biopsychosocial framework. Pediatric training and treatment typically occurs within a biomedical model whereby psychological and social factors are less emphasized in understanding a child’s functioning. In contrast, child psychiatrists and pediatric psychologists often employ biopsychosocial conceptualizations to understand a child’s functioning in which psychological and social contextual factors are emphasized.

Two practical differences between pediatrics and child psychiatry/psychology also impact consultation work: pace of work and work setting. The pace of work frequently differs between pediatric and psychiatric/psychological service settings, with a faster pace in pediatric settings when compared to child psychiatry and psychology. For example, C/L psychiatry consultations may take several hours to complete due to interviewing the child, family, and performing other assessments in response to the referral question. Psychotherapeutic interventions may take longer to initiate and realize benefits during the child’s hospitalization. The treatment culture of the inpatient pediatric ward also stands in contrast to psychiatric and psychological approaches to intervention. Inpatient treatment settings involve multiple treatment members who operate under time constraints, thus leading to a reduced amount of confidentiality and privacy. In contrast, contact over time and privacy are two basic ingredients that are typically necessary for psychotherapeutic interventions to be implemented and effective.

Biopsychosocial Influences on Pediatric Illness

For child and adolescent psychiatrists and pediatric psychologists, C/L processes involve an array of intersecting domains of knowledge and diverse areas of competency. Content knowledge in the areas of typical child development, child psychopathology, psychological and psychiatric treatment, and consultation with multiple professional disciplines has been identified as prerequisite to effective C/L work (5). The domain of pediatric C/L service is fertile ground for collaboration between child and adolescent psychiatrists and pediatric psychologists; for the latter, a basic understanding of disease process and its medical management as well as general understanding of pediatric hospital practice are also necessary for effective consultation.

Research has documented the complex interplay between a child’s biological functioning, psychological adjustment, social context, and development. An appreciation of each domain of the child’s functioning is important in approaching C/L work with pediatric populations. Examples of the interplay between child-centered variables, family context, treatment providers, and psychological adjustment abound within the pediatric psychiatry and psychology literatures. To illustrate the complex relationships between these domains, several research findings from the pediatric psychology literature are reviewed briefly.

Biological Variables

Medical conditions vary in the degree of central nervous system involvement, both in terms of disease pathology and its medical management and treatment. For example, children with traumatic brain injury or brain malignancy, by definition, have direct involvement of the central nervous system. Other conditions are not directly linked to central nervous system impairment but result in increased risk of brain involvement; for instance, children with sickle cell disease are at significant risk of central nervous system involvement, with up to 17% suffering cerebrovascular accidents (6). Other pediatric illnesses appear to pose little risk of central nervous system involvement, such as chronic allergies or asthma (7).

Pediatric treatment regimens may also be associated with psychosocial difficulties, due to involvement of the central nervous system, procedural pain, and other untoward effects of treatment. For example, declines in overall cognitive functioning and other neurocognitive abilities, such as attention, concentration, fine motor skills, and memory are well documented untoward “late effects” of cranial irradiation. The use of intrathecal chemotherapy to prevent central nervous system involvement in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia has also been associated with neurocognitive declines in such areas as nonverbal reasoning and academic achievement (8). Acute painful medical procedures, such as lumbar puncture, are associated with greater psychological distress and acute behavioral disruption.

Psychological Variables

Children hospitalized for pediatric illness vary in terms of prior psychological functioning as well as coping and adjustment to a diagnosis of medical illness, repeated hospitalization, and painful medical procedures (e.g., lumbar punctures). A psychological variable frequently examined in this area consists of a child’s cognitive appraisal and coping style, with children being variously categorized as information seeking/sensitizer or information avoiding/repressor. Research generally shows that children who use an information-seeking style of coping enjoy better outcomes when managing distress associated with medical procedures (9).

Social Variables

Family and caretaker variables are associated with children’s adjustment in a variety of areas such as functional outcomes, distress during medical procedures, and treatment adherence. For example, greater psychological adjustment of caregivers is associated with more favorable outcomes for children sustaining a traumatic brain injury (10). Parent behavior during painful medical procedures, such as lumbar puncture, is associated with children’s distress behavior, with parent apologizing for the procedure, explaining procedural events, and consoling correlated with greater child distress. Conversely, caregivers’ use of distracting techniques, such as blowing noisemakers or watching videotapes during procedures, has been shown to result in less child distress and better adaptation (11). Within the type I diabetes literature, the presence (versus absence) of parents during adolescents’ blood glucose testing has been associated with greater likelihood of inappropriate responding to episodes of hyperglycemia (12). Although participants were adolescents, findings suggest that additional educational intervention may be needed for parents to improve appropriate responding to hyperglycemia in management of type I diabetes.

Outside of the family context, there is growing recognition of the importance of peer relationships in affecting medical outcomes, such as the degree of support for treatment regimens. Researchers have begun to examine the influence of peer relationships in disease management and include peers in intervention programming. For example, peer involvement in an intervention for type I diabetes resulted in improved glycemic control (13). Specifically, the number of supportive peers involved in treatment was correlated with better controlled diabetes.

Developmental Perspectives

Children vary in their capacity to understand and cope with medical illness in terms of their cognitive development. Built upon Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, Lewis (14) described characteristic changes in children’s understanding of physical functioning and disease over time and recommended intervention be tailored to meet such perspectives. For example, as children develop from infancy to preschool age, they acquire greater knowledge and awareness of their bodies, as well as greater capacity to tend to bodily needs. Typically, preschoolers are able to name multiple body parts and verbalize concerns about bodily injury, such as “ouchies” or “boo-boos” (14). Cognitive development from preschool age to school age is associated with greater awareness and accuracy of the body in terms of its proportions, details, and internal structure. For example, preschool-aged children may view the body as a fluid-filled sac that will leak fluid if the skin is compromised. Later cognitive development results in greater understanding that separate organ systems exist within the body and that these organs can cause discomfort or pain, such as stomachaches.

Children’s beliefs and knowledge about the causes of disease and illness also develop in concert with greater cognitive reasoning abilities. Therefore, the consultant’s understanding of cognitive development may be used to guide patient education to increase understanding of the illness and improve adjustment (15). Children in the preoperational stage of development often fail to connect cause and effect between an event and illness. As children progress through concrete

operational stages to formal operations, their capacity to link cause and effect increases. For example, children in early stages of concrete operations (6–8) may identify themselves as bringing about their own illness, punishment for misdeeds (14). Children in this stage may need education that dispels belief that they have brought about their own illness. As children progress to formal operations, reasoning about the causes of illness are characterized by abstract thought, with explanations about illness invoking internal organs, dysfunction, and biological mechanisms that may be compromised. Adolescents are equipped cognitively to understand illness, treatment procedures, and make planful decisions about contributing to the management of their illness. Greater cognitive sophistication in adolescence, however, is often accompanied by beliefs of invincibility, which may impede adherence to treatment.

operational stages to formal operations, their capacity to link cause and effect increases. For example, children in early stages of concrete operations (6–8) may identify themselves as bringing about their own illness, punishment for misdeeds (14). Children in this stage may need education that dispels belief that they have brought about their own illness. As children progress to formal operations, reasoning about the causes of illness are characterized by abstract thought, with explanations about illness invoking internal organs, dysfunction, and biological mechanisms that may be compromised. Adolescents are equipped cognitively to understand illness, treatment procedures, and make planful decisions about contributing to the management of their illness. Greater cognitive sophistication in adolescence, however, is often accompanied by beliefs of invincibility, which may impede adherence to treatment.

Introduction of Two Biopsychosocial Models

As briefly illustrated earlier in the chapter, the interplay between biological, psychological and social functioning is important in informing psychiatric assessment and treatment of children and adolescents. Although historically a child-focused endeavor, more recent conceptualizations of C/L service have begun to incorporate biopsychosocial notions in understanding child and adolescent functioning (16). As such, broader theories of pediatric illness have been proposed to account for connections between medical disorder, child variables, family functioning, and community-based contexts.

Social-Ecological Framework

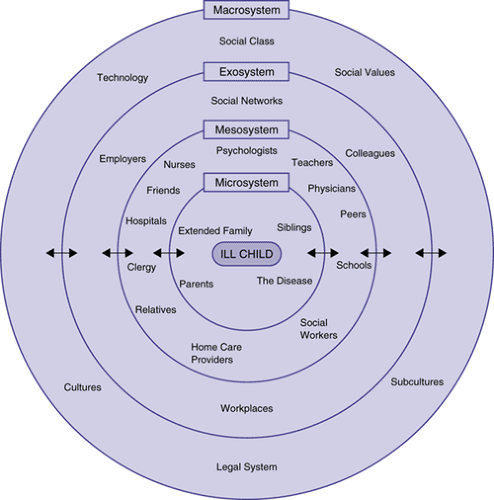

An exemplar of the biopsychosocial approach to psychological adjustment within pediatric populations has been adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s (17) social-ecological model of child development. Kazak’s adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s model (18) provides a comprehensive organization of influences on child and adolescent adaptation to disease and illness (Figure 7.1.1.1). Akin to Bronfenbrenner’s model, Kazak’s adaptation to pediatric populations features basic theoretical tenets of a) multiple layers of influence (nested systems) and b) bidirectionality of influence on psychological functioning and adjustment. Factors influencing a child’s functioning and adaptation are nested within systems that extend from intra-individual (e.g., cognitive functioning) to larger ecological influences (e.g., medical technology).

Orientation to Different Systems

As illustrated in Figure 7.1.1.1, systems of influence are nested within one another and represent diminishing causal influence on the patient’s adaptation and functioning. The innermost circle is symbolic of the child with pediatric illness and intra-individual factors that impact the child’s psychological adjustment and functioning. Examples of intra-individual variables include several of those introduced earlier, such as cognitive functioning and capacities for coping. The microsystem involves the patient’s most immediate social relationships, including parents, siblings, and extended families, and, particularly relevant for pediatric consultation, disease-related influences. Microsystem influences are deemed the most proximal and salient causal influences on the child’s adjustment. Mesosystem influences consist of more distal social and ecological influences on the patient’s adaptation, exemplified by peers, school personnel, and an array of medical and mental health providers within the hospital setting and beyond. Exosystem influences consist of a variety of contexts that impact social relationships and functioning within the mesosystem. Finally, macrosystem influences are those that impact the entire system, such as cultural beliefs, social values, and, particularly relevant to pediatrics, medical technology.

The Disability-Stress-Coping Model of Adjustment

Another example of a biopsychosocial approach to working with pediatric populations is the disability-stress-coping model of adjustment to chronic illness (9). Similar to Kazak’s model, the model represents a conceptual framework to organize and specify links between a range of biological, psychological, and social variables impacting psychosocial functioning. Built upon a risk-and-resilience framework, the model identifies biological, intrapersonal, and social-ecological variables that contribute to the child’s psychosocial adjustment. Within the model, stress is identified as the primary source for elevating the risk of maladjustment to chronic disease. Various sources of stress are identified, such as functional disability associated with illness and psychosocial stressors. A range of psychosocial stressors are identified, such as life transitions (e.g., moving; new school placement) and hassles associated with disease management. Resilience factors are identified as moderating the link between stress and psychosocial adjustment. Factors are identified in the areas of stress processing (e.g., coping), within-person factors (e.g., competencies), and social-ecological variables (e.g., parental adjustment).

History of Consultation and Liaison to Pediatrics

In the United States, the first consultation-liaison/psychosomatic medicine units were formally founded in the 1930s through the Rockefeller Foundation at Massachusetts General, Duke and Colorado. During the 1970s NIH began funding training grants to promote the growth of C/L psychiatry. By 2003, the field had formally adopted the name of psychosomatic medicine and gained approval as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties (19). In parallel, in the 1960s the field of pediatric psychology began to formally emerge, through which psychologists also began to conduct a range of clinical and research activities in similar medical settings. In 2001, the Society of Pediatric Psychology was formally designated as Division 54 of the American Psychological Association (20).

Range of Settings and Activities

Pediatric psychologists and psychiatrists conduct clinical services, research activities, preventive educational programs, and public advocacy across diverse settings. Roberts (20) delineated five settings in which pediatric psychology services are most commonly provided: 1) Inpatient medical center units (C/L services for acute and chronic illnesses such as neonatal intensive care units, oncology units, respiratory care units); 2) outpatient medical clinics (emergency departments, primary care centers, pain clinic, craniofacial, genetics, neurology); 3) outpatient clinics providing care for children with psychiatric problems; 4) specialty facilities (physical rehabilitation centers, developmental disabilities centers, hospice); and 5) camps or groups (summer camps for children with diabetes, support groups for parents of chronically ill children).

There is an equally broad range of clinical service activities that are performed by pediatric psychiatrists and psychologists. Accordingly, psychiatric assessment of child, adolescent and family adjustment is a core service provided by mental health consultants. Depending on the setting and concerns presented by the medical team, psychiatric assessments can be quite focused in scope, or involve a comprehensive multisystem evaluation approach as described above. Structured interview methods, including the formal mental status exam, as well as standardized behavioral or psychological instruments are typically included in assessment procedures.

Psychiatric consultants are also familiar with a broad range of psychotherapeutic interventions to address presenting problems such as depression, anxiety, adherence difficulties, procedural pain, and chronic pain. Increasingly, there has been an emphasis in the field on the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based or empirically supported treatments (21). Such treatments typically target disease-specific problems such as acute and chronic pain, medication adherence, coping deficits, or family conflict. Finally, the psychiatric consultant is also required to have the most current knowledge of psychopharmacological interventions for the pediatric patient to address a broad range of psychiatric symptoms, including depression, anxiety, delirium, withdrawal, and behavioral agitation.

In addition to these patient-based clinical services, pediatric psychiatrists and psychologists develop expertise in activities such as: development of programs for promotion of health and prevention of health and psychological problems; education programs for pediatricians and family physicians regarding general child development issues; advocacy regarding child health and mental health at the public health and public policy level; and applied clinical research (20).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree