The Contribution of Epidemiology to Psychiatric Aetiology

Scott Henderson

Introduction

Epidemiology deals with the overall patterns of disease. On one hand, people are unique with their own genetic endowment and life experiences. This idiographic paradigm is balanced by the nomothetic in which recurrent and predictable patterns are sought in the whole of humankind. It is the business of psychiatric epidemiology to determine the distribution of mental disorders in populations, the factors determining that distribution, and measures that may help in their prevention.

From their undergraduate years onward, clinicians see patients who have a disorder and who at the same time give a history of certain experiences from birth to their present. It may be tempting for both patient and doctor to accept that the patient’s recent experiences have some role in the onset of symptoms. But if the principles of epidemiology are brought into play, some questions need to be asked first. Being unwell may itself bias the recall of recent or distant experiences. What proportion of the general population have had the same experiences but not developed the disorder? What proportions have the same disorder but have not had these experiences? What proportions have the same disorder but have not reached health services? A simple two-by-two table is the simplest way to think this through (Table 2.7.1).

The columns are made up of persons in a population who have or do not have a particular disorder. The rows are the numbers who have or have not had a certain exposure. That exposure is being considered as a putative risk factor. It may be biological or psychosocial and may have taken place at any time from conception to the present.

Table 2.7.1 Cases and exposure: a two-by-two table | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The uses of epidemiology

In his celebrated monograph bearing this title, Morris(3) described seven uses of epidemiology. It continues to give us a framework for assessing the state of psychiatric epidemiology in relation to the biological and psychosocial conditions of the contemporary world. Morris’s list can be reinterpreted for our use as follows.

Completing the clinical picture

This means knowing about all the ways in which a disorder may present and what its usual course is. But it also means relating subclinical cases to fully developed ones. An excellent example here would be the anxiety, depressive, or somatization states seen in general practice or field surveys compared to the more severe syndromes specified in the international criteria and encountered by psychiatrists.

Community diagnosis

Here one obtains estimates of morbidity as it occurs at the general population level, not just in persons who have reached primary care or mental health services. Only by having such estimates of prevalence or incidence for whole populations can the size of the nation’s disease burden be determined. This is because community-based measures of morbidity include not only persons with treated conditions but also those who are symptomatic yet have not reached services.

Secular changes in incidence

This refers to the rise and fall of diseases in populations. For example, there is some evidence that schizophrenia has been dropping in incidence and becoming more benign in its clinical course; and it is likely that in many Western countries, depressive disorder has become more frequent in persons born since the Second World

War.(4) The suicide rate of young persons has indisputably increased in many industrialized countries. It is likely that eating disorders have increased in frequency and it is certain that the use of illegal drugs and AIDS are new arrivals and will be a continuing burden.

War.(4) The suicide rate of young persons has indisputably increased in many industrialized countries. It is likely that eating disorders have increased in frequency and it is certain that the use of illegal drugs and AIDS are new arrivals and will be a continuing burden.

The search for causes

Here, epidemiology is looking for aetiological clues. It is the substance of this chapter.

Applying population data to individual risk

In this, the focus moves from the population back to the individual. For example, if the annual incidence rate for schizophrenia is known in a population and if this information is age-specific, it is possible to estimate the probability that a person in a given age group will develop the disorder within the next year. This is the base rate, before one starts to consider risk factors such as family history. Next, by aggregating data on the course of schizophrenia, it is possible to estimate the chances of recovery for persons who are currently having their first episode. The common principle is that data based on large numbers of persons are used to make probability estimates for individuals.

Delineation of syndromes

This is done by examining the distribution of clinical phenomena as they occur in the population. It fits well with recent experience of repetitive strain injury, chronic fatigue syndrome, and posttraumatic stress disorder or its congeners.

Health services research

This begins with a determination of needs and of resources, then an analysis of services currently in action, and ends with attempts to evaluate them, including the costs. Research activity in this area has expanded greatly in recent years, driven by the forces of economic rationalism.

Prevention

To Morris’s seven uses of epidemiology should be added prevention, which Gruenberg(5) said was its ‘ultimate service’. All other uses are subsidiary to this. Examples are the current activity in the prevention of suicide in young persons and of alcohol or drug abuse. In these, the traditional medical approach of targeting high-risk groups should be contrasted with the epidemiological and population-based approach described by Rose.(6) One underrecognized fact is that knowledge about factors that determine the duration of a disorder can lead to prevention. This is because prevalence is the incidence rate times the duration. So shortening the duration will lower the prevalence. For example, if people with depressive disorder were treated earlier in primary care, the prevalence should fall. The prevention of a mental disorder is greatly helped by knowledge about aetiology, but it is not essential. For example, Snow did not know about the cholera vibrio when he had the water supply changed. Prevention is discussed further by Bertolotte in Chapter 7.4, prevention in child psychiatry by Lenroot in Chapter 9.1.4, and in intellectual disability by Kaski in Chapter 10.3.

Research on aetiology: three levels

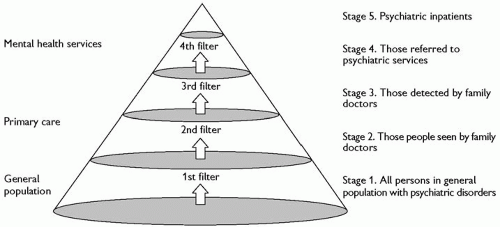

Epidemiological methods can be applied at any of the three levels: to disorders as these present in hospitals and specialist health services, in primary care, or in the general population. These are represented diagrammatically in Fig. 2.7.1 as a three-dimensional cone, derived from the seminal volume on pathways to care by Goldberg and Huxley.(7) The base of the cone consists of those in the general population who have clinically significant psychological symptoms (Stage 1). When these symptoms become unmanageable to self or to others, people seek help from their doctor or other health practitioners (Stage 2). But only some of them are recognized by the professional to have significant mental health problems (Stage 3). A small proportion may be referred to mental health services (Stage 4), of whom an even smaller fraction are admitted to inpatient care (Stage 5). Note that most teaching and the diagnostic criteria in international use are largely based on their authors’ experience in Stages 4 and 5, where patients are more severely ill!

There are two very different ways to express morbidity. The most common, and easiest to obtain, is prevalence, either at the time of assessment (point prevalence), 1-month, 1-year, or lifetime prevalence. The other is incidence, the number of new or fresh onset cases in a given period. For aetiological research, incident cases are emphatically preferable.

Three main designs

At any of these levels, research directed at aetiology uses one of three designs: cross-sectional, prospective longitudinal, or case-control. A cross-sectional study is often an excellent start, because it provides a picture of how much morbidity is present at one point in time and the variables most closely associated with this. But because it is only a ‘snapshot’, the cross-sectional study can rarely allow much to be said about causes. For example, in a community sample of several thousand adults, the data will show that persons with symptoms of anxiety or depression will tend to report having had more adversities. But it would be unwise to conclude that adversity contributes to the onset of symptoms. First, persons with anxiety or depression may be more inclined to report that they have had many troubles. This may be through selective recall of unpleasant events, because it is known that depressed people are more likely to remember bad times than good times.(8) Another mechanism is effort after meaning, whereby people try to account for feeling psychologically unwell. Next, symptomatic persons may be more likely to have unpleasant things happen to them as a consequence of their mental state. Lastly, persons with anxiety or depression may have certain personality traits or lifestyles that make them more likely to have troubled lives and also be vulnerable to common mental disorders.

Such problems in methodology can be resolved to some extent by using a prospective longitudinal design or cohort study. In this, a population sample is assessed at the start when most persons are psychologically well. In one type of cohort study, the sample may deliberately include a group who have had a particular exposure, such as a head injury or disaster, and an equivalent number who have not. At the start, data are obtained on personality, lifestyle, past health, and family history. The cohort is then re-examined at least once after an appropriate interval. Some will have developed symptoms. The research question is whether the putative risk factors that were assessed at the start were more frequently present in those who later developed symptoms. A design of this type yields considerably more information about the causal processes likely to be at work, either those leading to mental disorders or protecting against them. It also overcomes the problem of a putative risk factor really being a consequence rather than an antecedent of a disorder. But it is obviously very demanding in resources—human, administrative, and financial. It also takes a long time. For these reasons, epidemiologists often use the case-control method as a more practicable alternative.

Case-control designs have been underused in psychiatric research, but they can be a powerful strategy for identifying risk factors for a specified disorder.(9,10) The essence of the case-control design lies in obtaining data to complete the cells in Table 2.7.1. The aim is to find a sample of all persons in a population who have reached case level for a particular disorder and an equivalent number of persons who are similar in age, gender, and other variables, but who do not have the disorder, at least not yet. The cases should ideally be ‘incident’ or recent in onset. If instead, the study has to have recourse to all the cases of the disorder known to the service, that is, the prevalent cases, some will be long-standing and some more recent. This could lead to misleading results because a putative risk factor may show up as ‘positive’ not because it is a cause or true risk factor, but because it is associated with chronicity through prolonging the duration of the disorder. This problem can be avoided only by recruiting recent-onset or incident cases for case-control studies. The cases and controls are then asked about the various possible exposures. If the cases are unable to give information because they are cognitively impaired (as in dementia), at least one informant has to be found for each case, usually a partner or close family member.

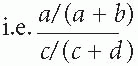

In Table 2.7.1, the important question is whether there are more persons in cell a than would occur by chance. We do not know the incidence of the disorder in all persons in the population who were exposed to each risk factor, nor do we know the number not exposed. Likewise, we do not know how many people in the population have recently developed the disorder. As a consequence, we cannot compare the incidence in those exposed and not exposed for the whole population. All we have are the data from the cases examined, who are necessarily only a fraction of all incident cases in the population; and data from a fraction of all healthy persons. But we can proceed as follows. First, the relative risk is calculated from Table 2.7.1. The relative risk is a/(a + b) divided by c/(c + d)

By simple algebra, this becomes

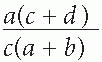

Then something very helpful can be done. Where a disorder is fairly uncommon in the general population, a will be very small compared with b, and c will be small compared with d. If we assume a negligible contribution by a in the term a + b, and by c in the term c + d, the relative risk will be nearly equal to

This is the odds ratio, which is an expression of the strength of a risk factor.

Whom to study: principles of sampling

The essential principle is that everyone in the true denominator (usually the total population within a defined geographical or administrative area) must have an equal probability of being included in the numerator. If this is not achieved, there is a likelihood of bias whereby the achieved sample may be systematically different in ways that could be important in the analysis. For example, the sample of cases should not differ from all the incident cases in that population in attributes such as level of education, age, or likelihood of having been exposed to a candidate exposure or risk factor. So in a study of the association between, say, sexual abuse in childhood and depressive disorder in adult life, the cases of depression should ideally be representative of all those with depressive disorder in that community and not just those reaching a particular service. See also Chapter 2.2 by Dunn.

Sample bias

In field surveys, it has long been accepted that not everyone who is in the ‘target sample’ will agree to be interviewed or will be available at the time the interviewer calls. It is common to find that

only 70 to 90 per cent are actually assessed. Furthermore, those who refuse or are repeatedly not available are known to be more likely to have the mental disorder under investigation. For this reason, the prevalence that is found will often be an underestimate. A putative risk factor may itself increase the chances of a person’s not being in a sample in the first place, of dropping out, or of dying during the study. Statistical methods are available for estimating how much error may have occurred due to refusals and how to correct for this in the conclusions drawn.

only 70 to 90 per cent are actually assessed. Furthermore, those who refuse or are repeatedly not available are known to be more likely to have the mental disorder under investigation. For this reason, the prevalence that is found will often be an underestimate. A putative risk factor may itself increase the chances of a person’s not being in a sample in the first place, of dropping out, or of dying during the study. Statistical methods are available for estimating how much error may have occurred due to refusals and how to correct for this in the conclusions drawn.

The other occasion when non-response is a problem is in longitudinal studies, where a sample is followed over several years. If a disorder with an increased mortality is the topic, such as dementia or schizophrenia, it is recognized that some cases will be lost at follow-up. This means that those who are successfully re-examined are a survival élite and are different in important ways from the original cohort. These distortions could lead to mistaken conclusions if the losses are not allowed for. Various techniques have been developed to handle these difficulties, including Bayesian methods which adjust final estimates on the basis of prior knowledge.(11)

Specifying the disorders

Diagnostic categories

The epidemiology of mental disorders could have made no real progress without methods for specifying the disorders to be investigated, then measuring these. Only in this way can research data be comparable between research teams, within and between countries. Having consistency in diagnosis has been made much easier through the development of the diagnostic criteria now in wide international use. The two systems are the International Classification of Diseases (10th Revision) (ICD-10) with its Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders; and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition (DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association. These classifications are described further in Chapter 1.9. Both are under revision.

Continuous measures of morbidity

Reliable and valid case ascertainment might be assumed to be the sine qua non for any progress in the epidemiology of mental disorders. But to use the traditional expression ‘case ascertainment’ nicely illustrates the very problem that has to be re-thought, because it implies a categorical structure in the morbidity that we wish to study. In a population, there are traditionally cases and non-cases. But this is not really how morbidity shows itself. As expressed by Pickering,(12) ‘Medicine in its present state can count up to two, but not beyond’. He was referring to hypertension, but others have argued that mental disorders also have dimensional properties.(6) The frequency distribution of their component symptoms such as anxiety, depression, or cognitive impairment is usually a reversed J-shape, with most people having none or only a few symptoms and progressively fewer persons having higher counts. A committee of clinicians in Geneva or Washington, whose experience is largely derived from teaching hospitals, has decided by consensus where the cut-point should be placed for persons to be ‘cases’. While this is entirely appropriate for some purposes, it may not always be a true representation of the underlying pathology. In statistical terms, it loses information.

It is not disputed that mental disorders exist in categorical states and that these have some utilitarian value: a depressive episode, Alzheimer’s disease, anorexia nervosa, or alcohol dependency are clinically realistic entities. What is proposed here is that, in epidemiological studies at the general population level, hypotheses about the aetiology require large numbers of respondents, solely because the base rates for such conditions are not large. But it is possible to identify persons with some symptoms of depression, of cognitive impairment, of abnormal eating, or of alcohol misuse. The score on a scale of these symptoms can become the dependent variable in an analysis of candidate risk factors. So it is usually more powerful statistically to look for associations between a putative risk factor and morbidity expressed as a continuous variable, rather than as a dichotomy of cases and non-cases.

When a continuous measure of common psychological symptoms such as the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)(13) (vide infra) is applied to a population, a unimodal distribution curve is found, with no break between so-called cases and normals. Rose(6) argued that there are three important consequences from this approach to studying morbidity. First, a characteristic of the community as a whole emerges. This is the mean and standard deviation of its GHQ scores. Second, this collective characteristic may show significant differences between men and women, geographical regions, social strata, and income groups. These differences are based on shifts of the entire distribution. The third consequence is that differences between these groups in the prevalence of probable cases (those with a score above a threshold) are related to different average scores in these groups. As Rose(6) concisely put it, ‘The visible part of the iceberg (prevalence) is a function of its total mass (the population average)’.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree