7

The Diagnostic Anatomy of the Inguinal Complex of Nerves

Originating in the lumbar plexus (T12 to L4), several peripheral nerves course distally through the inguinal region to provide motor and sensory innervation to the groin and thigh. Although damage of these nerves is uncommon, certain types of idiopathic, iatrogenic, and traumatic injuries may occur. Therefore, their anatomy and possible deficits remain important and will be discussed in this chapter.

The two major nerves of the inguinal complex are the femoral and obturator nerves, which are the primary output of the lumbar plexus. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, irritation of which causes meralgia paresthetica, as well as other nerves in the inguinal and genital region, will also be described. The inguinal complex of nerves controls thigh flexion, thigh adduction, and leg extension. Sensory coverage includes the groin, anterior and medial thigh, and the medial leg down to the arch of the foot.

Anatomical Course

Anatomical Course

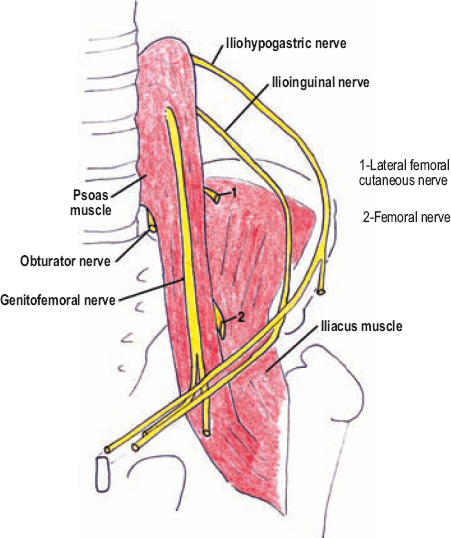

A general overview of the inguinal complex of nerves’ anatomical relationships with the iliopsoas muscles, pelvis, and inguinal ligament is illustrated in Fig. 7-1.

The Femoral Nerve

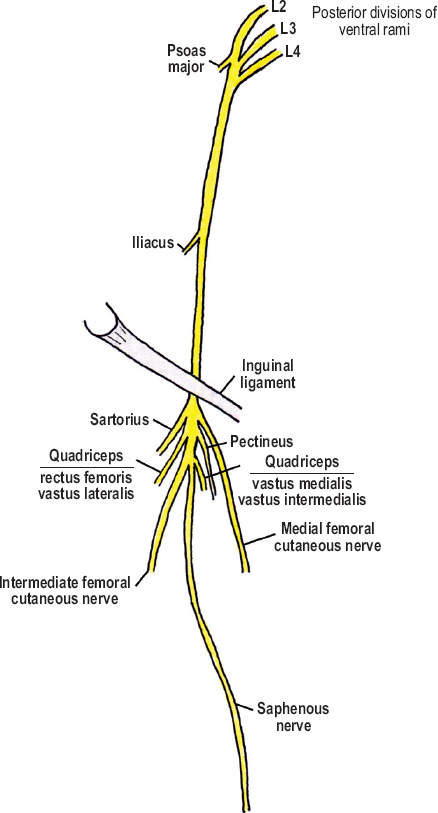

The femoral nerve is the largest branch of the lumbar plexus, being composed of the posterior divisions of the L2, L3, and L4 ventral rami. The anterior divisions of these ventral rami make up the obturator nerve (see below). These divisional contributions to the femoral nerve merge posterior to the psoas major muscle, and anterior to the transverse processes of the spine. Once formed, the femoral nerve runs inferiorly and laterally, in an oblique course down the pelvis, remaining under but near the lateral margin of the psoas major. The femoral nerve emerges from under the psoas major at the groove this muscle forms with the iliacus in the pelvis, approximately 4 cm proximal to the inguinal ligament. When the femoral nerve exits from under the psoas and passes over the iliacus muscle, it remains below the rigid iliacus fascia, which forms the roof of the iliacus compartment.

Figure 7-1 General anatomical relationships between the inguinal complex of nerves and the psoas major, iliacus, pelvic rim, abdominal wall, and inguinal ligament.

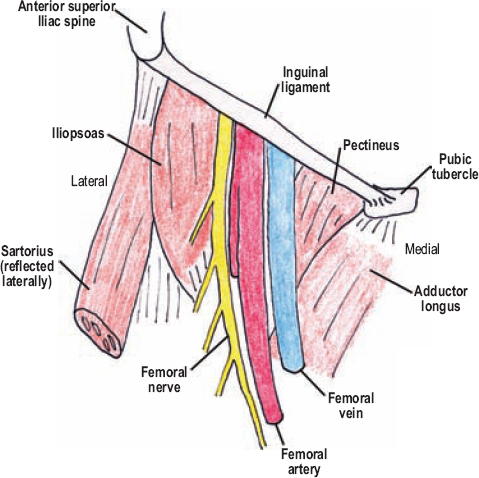

The femoral nerve passes deep to the inguinal ligament to enter the femoral triangle of the anterior thigh, where it remains lateral to the femoral artery (Fig. 7-2). The femoral triangle is bordered by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the sartorius muscle laterally and inferiorly, and the adductor longus muscle medially. The femoral nerve lies deep to the iliacus fascia, which extends from the pelvis to cover and protect the femoral triangle. Of note, a small window in the iliacus fascia is present over the femoral vein and medial half of the femoral artery, just below the inguinal ligament.

Figure 7-2 Femoral nerve in the femoral triangle. The femoral nerve passes deep to the inguinal ligament and enters the femoral triangle of the anteriorthigh, where it remains lateral to the femoral artery.

A few centimeters distal to the inguinal ligament, under the sartorius muscle, the femoral nerve almost immediately splits into numerous terminal branches. These branches include three cutaneous sensory branches: the medial femoral cutaneous, the intermediate femoral cutaneous, and the saphenous nerve. The remaining branches are motor nerves to the quadriceps, sartorius, and pectineus. The quadriceps is composed of four muscles: the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedialis, and vastus medialis. A common branch to the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis usually originates very proximal, and runs with the lateral femoral circumflex artery.

The saphenous nerve continues distally in a gradual, oblique course, from the femoral nerve near the inguinal ligament toward the medial knee. The saphenous nerve runs with the femoral artery and vein, deep and parallel to the sartorius muscle, along a groove between the adductor longus and vastus medialis (subsartorial canal). The saphenous nerve then enters the adductor canal (of Hunter) with the femoral vessels, but instead of passing into the posterior compartment of the leg, the saphenous nerve remains anteromedial to the knee. The saphenous nerve pierces the subcutaneous fascia at, or just distal to, the knee. It provides sensory coverage to the medial leg, medial malleolus, and arch of the foot.

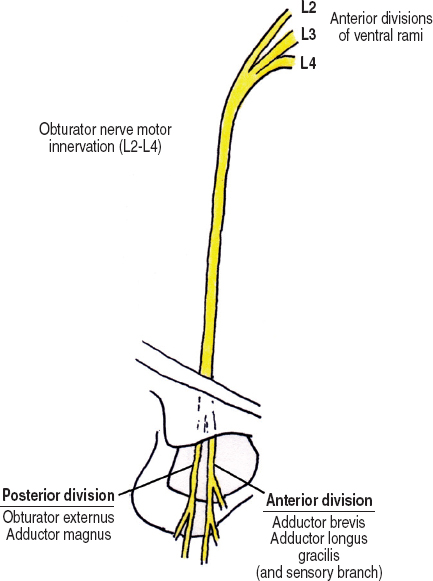

The Obturator Nerve

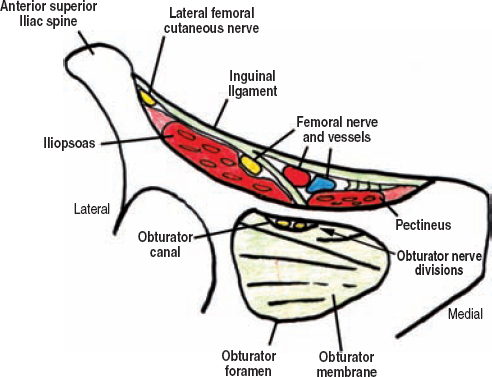

The obturator nerve is the second major nerve from the lumbar plexus, arising from the anterior divisions of the L2, L3, and L4 ventral rami. These spinal nerve contributions fuse to form the obturator nerve in the substance of the psoas major. Once formed, the obturator nerve makes it way under the psoas major to this muscle’s inferomedial border, and from there runs between the psoas and the iliac vessels through the pelvis toward the obturator foramen (Fig. 7-1). The large obturator foramen is mostly covered by the obturator membrane, upon which the obturator externus muscle originates. A hole in the obturator membrane near the most superolateral aspect of the foramen is called the obturator canal. The obturator nerve exits the pelvis via the obturator canal (Fig. 7-3).

Just prior to exiting the pelvis, the obturator nerve bifurcates into an anterior (superficial) and posterior division. Both of these obturator divisions pass through the obturator canal and perforate the obturator externus muscle, which runs from the obturator membrane to the proximal femur. Once piercing this muscle, these two divisions run deep to the pectineus muscle. The smaller, and deeper, posterior division branches upon the obturator externus, sending some branches under the adductor brevis to innervate a portion of the adductor magnus, a muscle that is also innervated by the tibial division of the sciatic nerve. The more superficial, anterior division runs over the adductor brevis upon which it ramifies. The anterior division passes deep to the adductor longus.

A cutaneous sensory branch from the anterior division originates quite proximally, usually where this division ramifies on the adductor brevis. This cutaneous branch passes deep to the adductor longus with an oblique trajectory toward the medial, inner thigh.

In a third of the population, an accessory obturator nerve is present, which originates from the anterior divisions of the L3 and L4 ventral rami. These patients have a normal, albeit smaller than usual, obturator nerve that follows its standard anatomical course. The accessory obturator nerve forms in the substance of the psoas major and passes with the normal obturator nerve medial to the psoas toward the obturator foramen. However, the accessory obturator nerve does not pass through the obturator canal, but instead passes over the superior pubic ramus. Once over the ramus, this nerve dives below the pectineus muscle to anastomose with the anterior division of the obturator nerve. When present, the accessory obturator nerve innervates the pectineus muscle, which usually receives its innervation from the femoral nerve.

In a third of the population, an accessory obturator nerve is present, which originates from the anterior divisions of the L3 and L4 ventral rami. These patients have a normal, albeit smaller than usual, obturator nerve that follows its standard anatomical course. The accessory obturator nerve forms in the substance of the psoas major and passes with the normal obturator nerve medial to the psoas toward the obturator foramen. However, the accessory obturator nerve does not pass through the obturator canal, but instead passes over the superior pubic ramus. Once over the ramus, this nerve dives below the pectineus muscle to anastomose with the anterior division of the obturator nerve. When present, the accessory obturator nerve innervates the pectineus muscle, which usually receives its innervation from the femoral nerve.

Figure 7-3 Cross-sectional view of the inguinal region from an anterior/inferior perspective. Structures that run from the pelvis to the thigh under the inguinal ligament are depicted. The obturator nerve’s divisions are shown passing through the obturator canal, which is formed by the obturator membrane and is located in the superolateral portion of the larger, bony obturator foramen.

The Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve

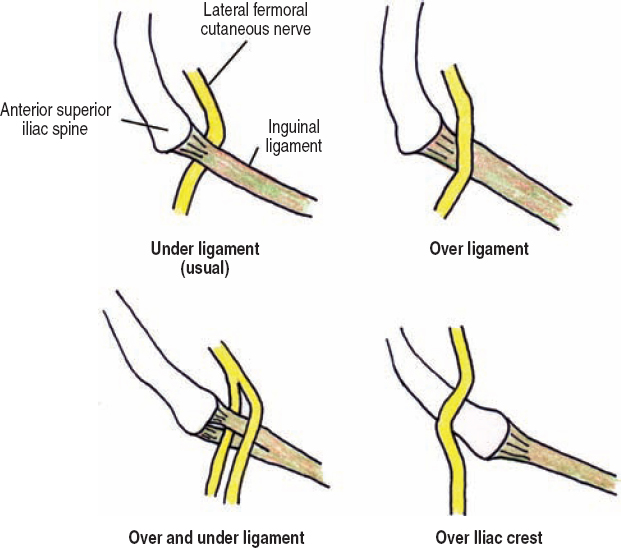

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve originates from the posterior divisions of the L2 and L3 ventral rami, just prior to where these two elements join the posterior division of L4 to form the femoral nerve. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve travels out from under the psoas major, looping around and upon the superior portion of the iliacus muscle toward the anterosuperior iliac crest. This nerve then exits the pelvis just medial to the anterosuperior iliac crest, underneath the most lateral portion of the inguinal ligament. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve usually passes under the inguinal ligament approximately 2 cm medial to the anterosuperior iliac spine.

Once outside the pelvis, this nerve immediately splits into two or more branches, pierces the fascia, and then runs subcutaneous over the lateral aspect of the thigh. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and its branches usually run superficial to the sartorius muscle.

The course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve in the region of the anterosuperior iliac spine is variable. The nerve can pass over the iliac crest, over the inguinal ligament, or even through a small hiatus in the ligament itself (Fig. 7-4). These variations are thought to predispose an individual to idiopathic entrapment of this nerve near the iliac crest (meralgia paresthetica). The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve may also run under or through the sartorius muscle. It may even originate, in part, from the femoral or genitofemoral nerves.

The course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve in the region of the anterosuperior iliac spine is variable. The nerve can pass over the iliac crest, over the inguinal ligament, or even through a small hiatus in the ligament itself (Fig. 7-4). These variations are thought to predispose an individual to idiopathic entrapment of this nerve near the iliac crest (meralgia paresthetica). The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve may also run under or through the sartorius muscle. It may even originate, in part, from the femoral or genitofemoral nerves.

Figure 7-4 Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve at the anterosuperior iliac spine. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve usually exits the pelvis just medial to the anterosuperior iliac crest, underneath the most lateral portion of the inguinal ligament. In this region, variations in its course are the rule, with the more common ones illustrated.

Other Nerves of the Inguinal Region

The ventral rami of T12 and L1 form a common trunk under the psoas major. This trunk then splits into the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, with the iliohypogastric being the more superior of the two. These nerves run mostly parallel to each other, first passing through the psoas major, and then piercing its lateral margin to run over the quadratus lumborum muscle.

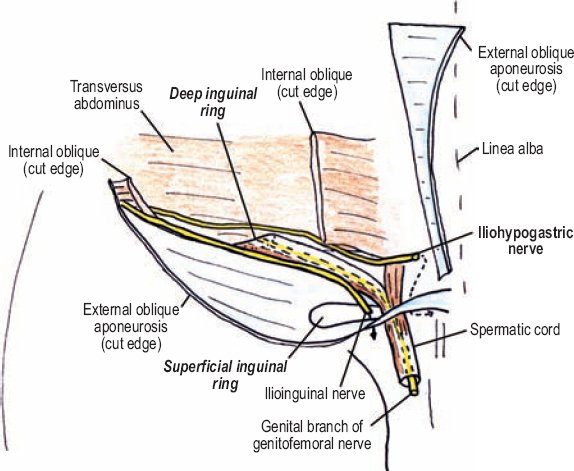

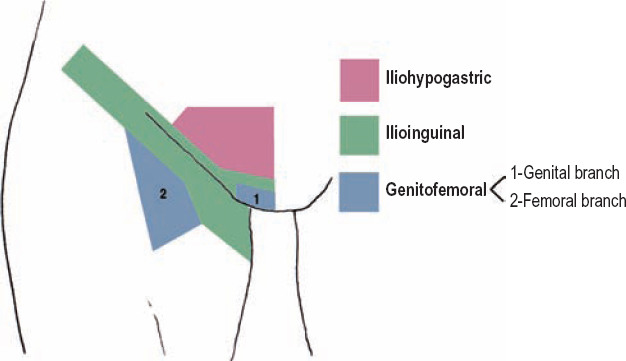

The iliohypogastric nerve perforates the transversus abdominis muscle over the iliac crest, and runs around the flank between this muscle and the internal oblique. Immediately superior to the anterosuperior iliac spine, a lateral branch of the iliohypogastric nerve perforates both the internal and external oblique muscles to become subcutaneous to innervate the superior lateral gluteal region. The remaining portion of the iliohypogastric nerve continues toward the midline, entering the distal inguinal canal, and passing through the superficial inguinal ring to become subcutaneous in the hypogastric/suprapubic region (Fig. 7-5).

The ilioinguinal nerve also passes around the flank toward the inguinal region, just caudal to the iliohypogastric nerve. The ilioinguinal nerve, however, pierces both the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles to run between the latter and the external oblique. This nerve gives sensory branches as it runs adjacent to the spermatic cord and cremaster muscle in the inguinal canal, eventually becoming subcutaneous with the medial branch of the iliohypogastric nerve through the superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 7-5).

The genitofemoral nerve is made up of branches from the L1 and L2 spinal nerves. Once formed, this nerve passes through the psoas major muscle and perforates its anterior margin just medial to the psoas minor muscle (when present). The genitofemoral nerve then passes distally adjacent to the ureter, eventually splitting into a genital and femoral branch just proximal to the inguinal ligament. The femoral branch passes under the inguinal ligament just lateral to the femoral artery, becoming subcutaneous in the femoral triangle (Fig. 7-5). The genital branch enters the deep inguinal ring, passes through the inguinal canal within the spermatic cord, and emerges from the superficial inguinal ring to innervate a portion of the genitalia.

Figure 7-5 Course of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves in the inguinal canal (right side, anterior view). The genitofemoral nerve runs along the psoas muscle and splits into a femoral and genital branch. The femoral branch passes under the inguinal ligament, while the genital branch enters the deep inguinal ring to pass distally within the spermatic cord. Portions of both the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves also pass within the inguinal canal, but not within the spermatic cord.

A common variation is for the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves to be derived only from the L1 spinal nerve, not T12.

A common variation is for the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves to be derived only from the L1 spinal nerve, not T12.

Motor Innervation and Testing

Motor Innervation and Testing

The Femoral Nerve

The femoral nerve controls thigh flexion at the hip, and leg extension at the knee (Fig. 7-6). The first muscle innervated by the femoral nerve is the psoas major. Co-innervation to this muscle also arises directly from the lumbar plexus (ventral rami). The second muscle innervated by the femoral nerve is the iliacus, which is in the pelvis. These two muscles, along with the psoas minor, when present, insert into the proximal femur to mediate thigh flexion at the hip. These muscles, collectively termed the iliopsoas (L2-L4), are tested together by having the patient raise the thigh against resistance (Fig. 7-7). The patient should be either seated or supine.

Figure 7-6 Motor innervation from the femoral nerve (L2-L4).

Figure 7-7 Iliopsoas (L2-L4) assessment: The psoas major and iliacus muscles (collectively termed the iliopsoas) are tested together by having the patient raise the knee (flex the thigh) against resistance, with the patient either sitting (shown) or lying supine.

Upon entering the femoral triangle and branching extensively, the femoral nerve innervates the pectineus, sartorius, and quadriceps muscles (L2-L4). The pectineus runs from the anterior pelvic rim (near the pubic tubercle) to the proximal femur. Together, the pectineus, psoas major, and iliacus, form the floor of the femoral triangle, with the latter two muscles lying deeper and more lateral than the pectineus. The pectineus cannot be isolated on exam, and therefore is not discussed further. The sartorius, or tailor’s muscle, runs from the anterosuperior iliac spine, obliquely down the leg to the medial knee, inserting into the anterior tibial tubercle. The sartorius muscle has a complex function, but in essence, abducts, flexes, and externally rotates the thigh. To semi-isolate this muscle, start by having the patient seated. Then instruct him or her to place the foot on the contralateral knee by dragging it up the shin (Fig. 7-8). Contraction of the sartorius may be palpated.

The quadriceps muscles mediate leg extension at the knee. The rectus femoris and vastus lateralis often share a common branch of the femoral nerve; the vastus intermedialis and medialis usually have their own branches (they also can share a common branch). With the patient seated, the quadriceps are tested by applying resistance against leg extension (Fig. 7-9). The muscle mass of the quadriceps should be observed and palpated because the sartorius (femoral nerve) and tensor fascia lata (superior gluteal nerve) may deceptively substitute for leg extension in some patients.

Figure 7-8 Sartorius (L2-L4) assessment: The sartorius muscle abducts, flexes, and externally rotates the thigh. To semi-isolate this muscle, start by having the patient seated. Instruct him or her to place the foot on the contralateral knee by dragging it up the shin. Contraction of the sartorius may be palpated.

Figure 7-9 Quadriceps (L2-L4) assessment: With the patient seated, the quadriceps are tested by applying resistance against leg extension. The quadriceps’ muscle mass should be observed and palpated because the sartorius (femoral nerve) and tensor fascia lata (superior gluteal nerve) may substitute for leg extension.

The Obturator Nerve

The anterior division of the obturator nerve provides motor fibers to the adductor brevis, adductor longus, and gracilis (Fig. 7-10). This pattern of muscular innervation makes sense, considering the obturator’s anterior division runs between the first two muscles and ends near the third. The posterior division innervates the obturator externus, and terminates by innervating a small portion of the adductor magnus, deep to the adductor brevis. To test obturator nerve motor function (i.e., the adductors, L2-L4), have the patient squeeze the thighs together with resistance placed at the inner knees (Fig. 7-11).

Innervation of the adductors is variable, with the adductors longus, brevis, and magnus often receiving innervation from both, or either, divisions of the obturator nerve.

Innervation of the adductors is variable, with the adductors longus, brevis, and magnus often receiving innervation from both, or either, divisions of the obturator nerve.

Other Nerves of the Inguinal Region

The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves provide motor branches to the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The ilioinguinal nerve also innervates the pyramidalis muscle, which, when present, can be tested with electromyography. The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve innervates the cremaster muscle, which helps mediate testicular thermoregulation by elevating the ipsilateral testicle. This reflex may be tested by applying light touch to the inguinal region and observing ipsilateral testicular elevation. The cremaster reflex is an unreliable clinical finding, however.

Figure 7-10 Motor innervation from the obturator nerve.

Figure 7-11 Adductor (L2-L4) assessment: Have the patient squeeze the thighs with resistance placed at the inner knees.

Sensory Innervation

Sensory Innervation

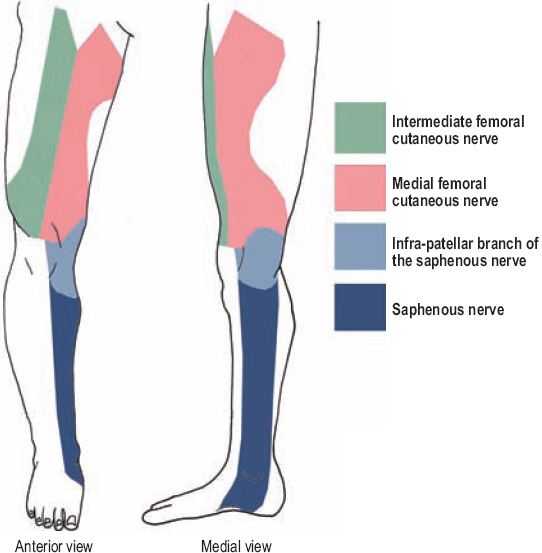

The Femoral Nerve

The femoral nerve’s sensory territory includes the anterior and medial thigh, as well as the medial leg and foot via the saphenous nerve (Fig. 7-12). The medial femoral cutaneous nerve branches from the femoral nerve in the femoral triangle and carries sensation from the medial thigh, mostly from the distal medial thigh (the proximal, medial thigh is covered more by the obturator nerve). The intermediate femoral cutaneous nerve also branches from the proximal femoral nerve in the thigh and covers sensation on the anterior (and somewhat medial) aspect of the thigh. Overall, an autonomous sensory zone for the femoral nerve is over the distal, anterior thigh.

The saphenous nerve’s sensory territory includes the medial knee, medial leg, medial malleolus, and the arch of the foot. Mostly small, unnamed branches of the saphenous nerve provide this cutaneous innervation. On the medial knee, however, the saphenous nerve frequently has a large cutaneous branch called the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve.

The Obturator Nerve

As mentioned, the obturator nerve’s anterior (superficial) division has a proximal sensory branch that passes under the adductor longus and perforates the subcutaneous fascia of the thigh. This branch provides sensation to the medial thigh region (Fig. 7-13). Sensory loss in this area is not always present with complete obturator palsies, and therefore is not considered autonomous.

Figure 7-12 Femoral nerve sensory innervation. The femoral nerve’s sensory territory includes the anterior and medial thigh, as well as the medial leg and foot via the saphenous nerve.

Figure 7-13 Obturator nerve sensory innervation (medial view). The obturator nerve’s anterior (superficial) division has a proximal sensory branch that passes under the adductor longus and perforates the fascia of the thigh. This branch provides sensation to the medial thigh region.

The Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve’s sensory territory includes the anterior, lateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 7-14). This nerve has an autonomous zone, which is located on the mid-lateral thigh.

Other Nerves of the Inguinal Region

The iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves all provide significant sensory coverage of the inguinal and pubic regions (Fig. 7-15). Their sensory territories overlap, but semi-autonomous zones do exist. The iliohypogastric nerve provides sensation to the suprapubic region. This nerve also gives a lateral cutaneous branch that passes over the iliac crest and innervates the upper, lateral buttock. The ilioinguinal nerve passes through the inguinal canal and provides sensation to the skin overlying the inguinal ligament, upper medial thigh, and mons pubis/base of the penis. For the genitofemoral nerve, its femoral branch passes under the inguinal ligament to cover the femoral triangle, whereas the genital branch passes within the spermatic cord to supply the scrotum/labia.

Clinical Findings and Syndromes

Clinical Findings and Syndromes

The Femoral Nerve

Injury to the femoral nerve is usually iatrogenic. Causes include gynecological procedures, femoral artery puncture for catheterization, arterial bypass procedures, hip surgery using methylmethacrylate, and pelvic surgery for tumors. Traditionally, an abdominal hysterectomy is the operation most frequently associated with femoral nerve damage. Trauma may also cause femoral nerve injury, including gunshot wounds to the groin and pelvis, lacerations, and hip/pelvis fractures. Expanding retroperitoneal (psoas or iliacus compartment) and femoral triangle hematomas from anticoagulation, trauma, or catheter placement may also cause femoral injury. Although proximal diabetic neuropathies frequently involve the femoral nerve, this nerve is rarely affected in isolation. Usually the lumbar spinal nerves, the lumbosacral plexus, and other peripheral nerves are involved simultaneously.

Figure 7-14 Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve sensory innervation. This nerve’s sensory territory includes the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. This nerve has an autonomous zone, which is located on the lower, lateral thigh proximal to the knee.

Figure 7-15 Sensory territory of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves. These nerves all provide significant sensory coverage of the inguinal and pubic regions. Although their coverage overlaps, semi-autonomous zones do exist. For the iliohypogastric nerve, it is the suprapubic region. For the ilioinguinal nerve, it is the inguinal ligament region. For the genitofemoral nerve, it is the femoral triangle (femoral branch) and scrotum/labia (genital branch).

Patients with significant femoral neuropathies often complain of incoordination or buckling of the knee and not paralysis per se. These patients have the most trouble standing from a seated position, as well as climbing stairs. A frontward kick is not possible. Sensory loss may be confirmatory, and includes the anterior thigh (intermediate femoral cutaneous nerve), lower medial thigh (medial femoral cutaneous nerve), medial knee (infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve), and medial leg and foot (saphenous nerve).

For patients with a suspected femoral neuropathy involving the iliopsoas muscle, which indicates a very proximal lesion, one should make certain to examine thigh adductor strength. If thigh adduction is weak, a lesion affecting the lumbar plexus, or multiple spinal nerves (i.e., L2–L4), is more likely. Imaging should be performed. Furthermore, a femoral neuropathy should be differentiated from a L4 radiculopathy. Both femoral neuropathy and L4 radiculopathy can manifest with quadriceps weakness, an absent knee jerk, and medial leg (shin) numbness in the saphenous territory. However, only a radiculopathy would have concurrent thigh adductor (L2–L4), anterior tibialis (L4–S1), and posterior tibialis (L4–L5) weakness. Therefore, these three muscles should also be closely examined in these patients.

Idiopathic entrapment of the saphenous nerve has been reported at the adductor canal in the distal, medial thigh. Prolonged or absent sensory conduction velocities in the saphenous nerve distal to the canal may occur. To avoid damage to the femoral artery, ultrasound guidance should be used during diagnostic nerve blocks in this region. Surgical release of the adductor canal may be indicated for select patients.

Rarely, patients may present with spontaneous and isolated numbness in the territory of the saphenous nerve’s infrapatellar branch (i.e., gonyalgia paresthetica). The cause is uncertain.

Rarely, patients may present with spontaneous and isolated numbness in the territory of the saphenous nerve’s infrapatellar branch (i.e., gonyalgia paresthetica). The cause is uncertain.

The Obturator Nerve

Patients with obturator palsies have weak thigh adduction and a variable amount of medial thigh sensory loss. The adductor tendon reflex may be absent, although this reflex may be absent in normal subjects. Injury to the obturator nerve is rare, but may be caused by penetrating trauma to the inguinal region or pelvis. As with the femoral nerve, iatrogenic etiologies are most common, and occur after pelvic surgery, especially for tumors. These injuries may be from direct manipulation or transection of the nerve, or more commonly, from a retractor stretch injury. Sometimes motor and sensory deficits are minimal to absent, and the patient only complains of pelvic/groin pain radiating to the medial thigh. If a neuroma occurs in this latter case, then a Tinel’s sign may be present in the groin or lateral vaginal wall. Injury to the accessory obturator nerve may also occur where it passes over the superior pubic ramus.

To exclude a lumbar plexus lesion, or radiculopathy (e.g., L3, L4), in patients with suspected obturator palsies, normal strength in the quadriceps and an active knee jerk should be documented.

Idiopathic obturator nerve entrapment by a fibrous arch in the obturator canal has been reported. These patients present with groin discomfort and pain radiating to the medial thigh. Although adductor strength is often normal in these patients, needle electromyography of the thigh adductors may help confirm the diagnosis. A test infiltration of anesthetic where the nerve is most tender may be both therapeutically and diagnostically useful.

The Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve (Barnhardt–Roth Syndrome)

Irritation of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is referred to as meralgia paresthetica (Barnhardt–Roth syndrome). Patients report numbness, paresthesias, pain, and/or hyperesthesia on the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. The etiology of this syndrome is usually considered idiopathic; however, it can often be related to repetitive, minor trauma or irritation. Patients sometimes report worse pain with standing and walking, and relief with flexion at the hip or sitting. Most symptoms are mild and self-limiting. Examination reveals sensory changes, especially hyperesthesia, on the lateral thigh. One provocative examination maneuver is to extend the thigh at the hip, which places the nerve on stretch and may thereby exacerbate the patient’s symptoms. Deep palpation along the lateral inguinal ligament may be tender. A Tinel’s sign is usually absent. The diagnosis may be confirmed with an injection of local anesthetic, which should ameliorate the symptoms. However, considering the anatomical variability this nerve exhibits (Fig. 7-4), there are many false-negatives with this test. Sensory conduction velocities may aid in the diagnosis.

An anomalous course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve may predispose one to neuropathy. Other predisposing conditions include obesity, ascites, and pregnancy: The protuberant abdomen is thought to distort regional anatomy and predispose one to meralgia paresthetica. Conversely, extreme weight loss is also associated with this disorder. Diabetes does not appear to be related. An autosomal dominant form of familial meralgia paresthetica has been reported.

An isolated neuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve can be readily differentiated from a femoral or lumbar plexus lesion because the latter diagnoses cause more extensive sensory loss over the anterior/medial thigh, as well as motor weakness. The more problematic differential is that from a L2 radiculopathy, which affects the upper, lateral thigh. However, a L2 radiculopathy causes pain or numbness extending more over the anterior and medial aspect of the upper thigh than expected in meralgia paresthetica. Furthermore, a L2 radiculopathy may also cause iliopsoas weakness.

Inguinal Neuralgia

The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves may be disrupted or damaged secondary to transverse abdominal incisions (e.g., hysterectomies or other lower quadrant procedures), or during inguinal hernia repairs. Damage to either nerve may cause back, inguinal, and scrotal/labial pain. To confirm the diagnosis of an iliohypogastric or ilioinguinal neuropathy, three criteria should be fulfilled: (1) history of a surgical procedure involving the abdomen or pelvis, (2) sensory changes in the suprapubic (iliohypogastric nerve) or along the inguinal ligament (ilioinguinal nerve), and (3) anesthetic infiltration of these nerves near the anterosuperior iliac spine produces relief. As mentioned, sensory testing in the groin helps distinguish which of these two nerves is involved.

Although rare, the genitofemoral nerve may be damaged during inguinal hernia repair or gynecological procedures. Previous appendicitis or psoas abscesses can also damage this nerve on the anterior margin of the psoas muscle. Genitofemoral neuralgia pain occurs in the inguinal region, scrotum/labia, and/or femoral triangle. Focal sensory loss over the femoral triangle helps confirm this diagnosis. A local nerve block of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, just medial to the anterosuperior iliac spine, would fail to alleviate symptoms that are from an irritated genitofemoral nerve, which does not pass through this region. However, a paraspinal block of the L1 and L2 spinal nerves, which blocks the genitofemoral nerve (and partially the ilioinguinal and/or iliohypogastric nerves), should relieve the pain.

If a patient with inguinal neuralgia has back pain or no history of previous inguinal or abdominal surgery, then a L1 radiculopathy should be ruled out with magnetic resonance imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree